ASC Cinematographers on Breaking into the Business, Fostering Trust, Fighting for Shots and More

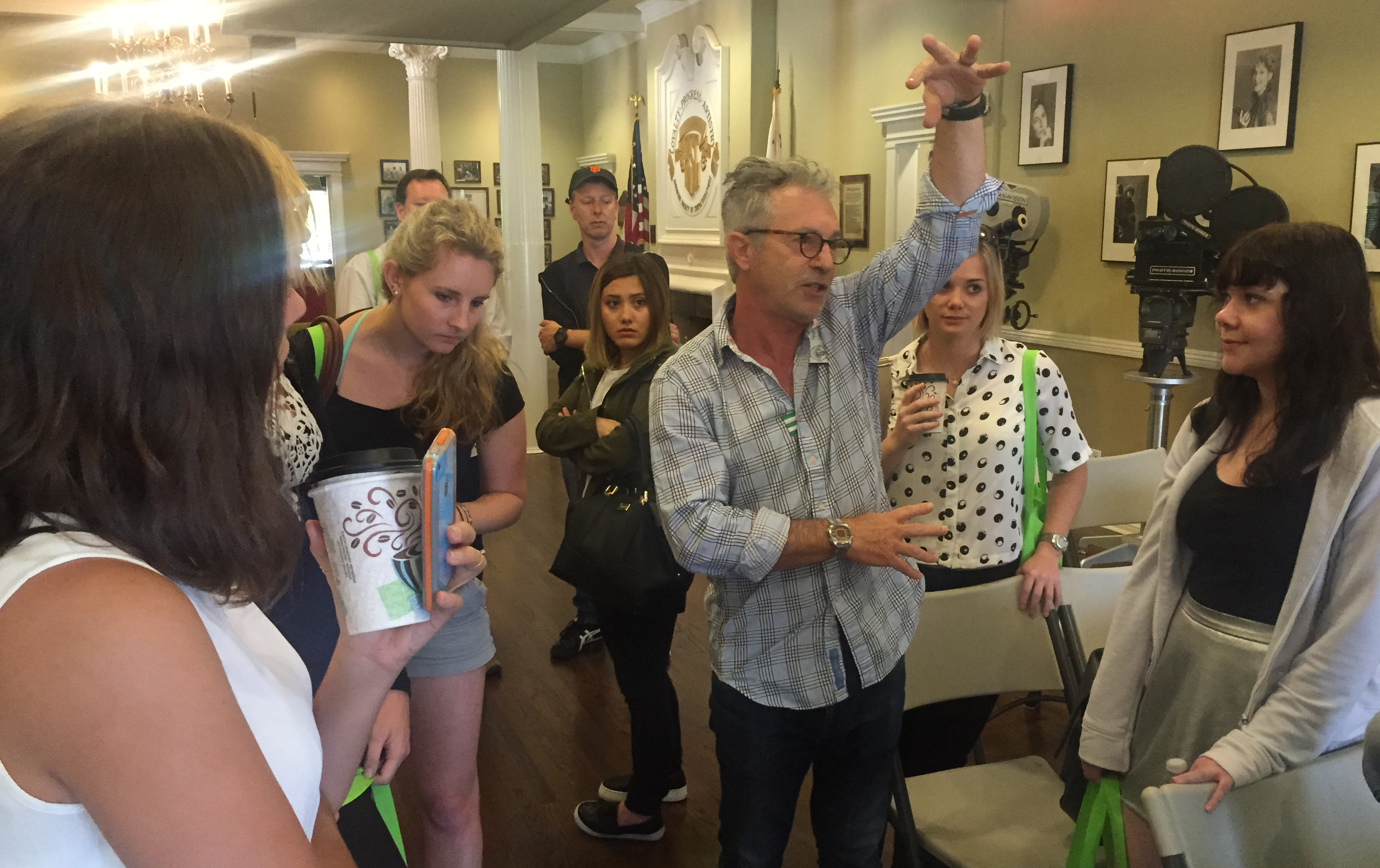

How to gain a foothold in the industry, the importance of trust in the creative process, and whether to fight for a shot were some of the topics addressed by seven ASC cinematographers in a recent Q&A session conducted by the ASC’s Education and Outreach committee, which welcomed students from Australia’s Queensland University of Technology.

The students visited the Clubhouse July 7 to speak with Bill Bennett, Patrick Cady, Peter Levy, Paul Maibaum, Peter Moss, Haskell Wexler and committee chair George Spiro Dibie, who also served as moderator for the two-hour discussion.

Bennett has been a top commercials cinematographer for two decades; Cady's recent credits include the series Rectify and Body of Proof; Levy won Emmys for the Californication pilot and the telefilm The Life and Death of Peter Sellers; Maibaum's credits include the series Sons of Anarchy and Baby Daddy; Moss' credits include the features Tell the World and The Cutter; Wexler won Academy Awards for Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and Bound for Glory; and Dibie won five Emmys, two for the series Growing Pains.

The students kicked things off with a question for Moss and Levy, who both came up in Australia’s film industry and are also members of the Australian Cinematographers Society. Here are some highlights from the conversation:

What’s your advice to someone who wants to break into the Hollywood system as a foreigner?

Levy: Every Australian who’s come here and had some success has come a different way. I got lucky because a director I’d worked with in Australia [Stephen Hopkins] was asked to do A Nightmare on Elm Street 5 [1989], and he insisted on me and brought me over. Skill alone is not enough. This is where the world’s best in the field of entertainment work. The main things that will work in your favor are your network and lucky breaks. In some ways, you’ve got to be seen as part of the food chain here [before your work is noticed]. You might not get a break for two years. Without contacts you won’t get far.

Moss: I was asked to come over to do a film with Kris Kristofferson [Flashpoint, 1984]. It was a 40-day schedule, and that was long enough to get me into the union, which was much tougher to get into at that time. Then, other people helped me with immigration.

Dibie: There are a lot of non-union opportunities on reality shows — that’s one way to start out. But remember: for every job there are a hundred or more applicants. Contacts will definitely help.

What’s the best way to gain a foothold in such a competitive industry?

Cady: Be that indispensable person on set. Also, keep your monthly nut low; live in the cheapest place you can tolerate. You want to be able to make some choices out of what drives you artistically, and that will be easier if your expenses are low.

Dibie: You might only work one or two days a week, so watch every penny you make. It’s very hard in the beginning, but do it. And smell good! I’m not kidding — you’re working with stars!

Bennett: I moved here from Texas with a reel of student films, and after two months my money was running out. I happened to walk by a stage and noticed they were building sets. I had built sets in college, so I walked in and asked for a job doing that. The foreman knew I wanted to be on the camera side, so eventually he put me on as a standby carpenter, and I started meeting more people. I met Ron Dexter [ASC], a brilliant director/cameraman who made commercials, and he became my mentor. He took me on, and I worked my way up as a first grip, key grip, assistant and then operator. Ron had one rule: ‘I don’t mind seeing a mistake on Take 1, but I don’t want to see it on Take 2.’ It was survival of the fittest, but the business is still that way. You must develop your craft and be technically competent so that when the opportunity is presented you, you can climb that step and do a good job.

Moss: I started as a loader in Sydney on a tiny film, an awful film, called Stone [1974]. I just walked into a studio, and they happened to be starting that film, and no one else wanted to do the job for the money. I did. I worked my way up over a long period; it took me 10 years to become an operator.

Levy: In the days of shooting film, there was an informal apprenticeship, and calling yourself a cinematographer after less than 12 years as an assistant [wasn’t done]. In 1969, I assisted on my first documentary. In 1984, I could shake a cinematographer’s hand and say, ‘I am one, too.’ That meant you were a master of your craft and could shoot anything. Be a nice person who does consistently good work — those are probably the only things you can control. After that, it’s a crapshoot.

Wexler: Ask yourself why you’re interested in telling stories through filmmaking. How does your work relate to your view? As ASC members, we want you to be more than good shooters who have jobs; we want you to be engaged artists. That will keep you going even if you don’t make much money.

How do you begin to conceive a creative vision for a project?

Dibie: In TV, this process starts with the script, but the style of the show is set by the executive producer/show runner. That’s the person the cinematographer has to please. Directors usually come and go each week [for each episode].

Bennett: On commercials, a lot of the creating has already been done by the time the cinematographer comes on — the agency has developed boards, and the director has fleshed out the concept. I have to please not just the director and the production-company producer, but also the agency people, who have veto power over everything we do. Then there’s the client, who can veto anything at any time because he’s paying. It can be a minefield to walk through.

Maibaum: It starts with getting inside the script and getting inside the director’s head and becoming a facilitator, a collaborator. You should also become really good friends with the production designer. Then, it’s finding a hook for yourself as to what the story is you’re telling; you can keep that to yourself and ask others to express their take. You must be able to listen. It’s an additive process, and whoever has the best idea wins.

Cady: When I read a script, my most common note is HTS: how to show? Remember that filmmaking can only be what people say, what people do, and the difference you show between those things, which is going to make all the drama in the story. If I’m not sure what a character is doing or why, I’ll ask the director, and a good director will have the answer. That answer will tell me the shot instantly. The first time I read a script, I try not to think about the budget, but at the same time, the cinematographer is the gatekeeper to the dream of practically realizing that vision, and you’ve got to raise certain flags early. There might be a sentence that says, ‘Atlanta burns.’

Moss: The first time I read a script, I always fall into the trap of visualizing certain shots, and even, cheekily, inventing them. On the second or third reading, I sense the pace of it. I was an operator for a very long time, and operators often contribute to the pace subconsciously — through their method of panning, for instance. I also think about ways to open the story up; scripts often seem claustrophobic to me. I always want to insert a couple of really wide shots with tiny figures, and that usually gets me into trouble.

Levy: Initially it’s a process of elimination: how much time, money and crew do you have? Then it’s a matter of manipulating what you’ve got. Don’t get attached to anything; be prepared to turn on a dime at any time. On the pilot for 24 [2001], we were going to have a love scene between two teenagers under Santa Monica Pier at night. It was perfect in my mind: the Ferris wheel in background, light coming down through the slats in the boardwalk. I loved that shot as soon as I knew I was going to do it. For a bunch of reasons, mostly to do with locations, we ended up shooting the scene on the roof of a furniture warehouse in Van Nuys. And it was fantastic, better than it would have been under the Santa Monica Pier. You have a natural sense of taste and style, and that will emerge in your work.

Do you ever fight for a shot?

Maibaum: I will fight to make sure everyone is respected, and I’ll fight to try to get things moving, but I will never fight for a shot, fight for a setup. If fighting with the director is your mindset going in, think differently. You have to be a collaborator and know when to let go. It’s important to care deeply about what you do, but I believe audiences don’t watch movies or TV programs because of the way they’re shot. They’re attracted by those actors or the story and sometimes by the director. If there’s incredible acting and an amazing script and subpar cinematography, the project can still succeed.

Moss: If time is the thing that’s making you lose the shot, I don’t think you can dig your heels in. You’ll just get fired. The skill of our job is creating something within certain budgetary and time parameters — and also creative parameters, because there are a couple of people who are more important than you creatively, and their parameters are going to stand in your way. You just have to be humble in this job.

Levy: You have to fight for important shots, but at some point you have to give up. Our job is essentially to say yes to the director, but at the same time, we are the custodians of the visual style, the visual coherence of the piece of work. Once the cinematographer stops caring, there’s no one to pick up the slack. Where that fine line is [between] digging your heels in or acquiescing to the will of production, I don’t know, and I’ve been doing this for 46 years.

Cady: If the director has a different idea, all you can do is present your idea several times and then let it go. Sometimes, if you’re working with a less visually experienced director, you can kind of shepherd things. I’ve been shooting mostly single-camera television lately, and I’ll often try to get [some lighting] up to what I think the room might look like before we do our blocking rehearsal. If it’s just the work lights on the stage, a director who doesn’t have a lot of visual experience might not know why it’s so important for you to be against the wall, looking toward the window. If some of the lights you plan to use are on, and you’re watching the rehearsal from the angle you think is best, and you have your viewfinder with a lens at the lens length you want, the director can come over and take a look, and you can say, ‘I was thinking something like this.’

What's your collaboration like with your gaffer?

Maibaum: As I’ve matured, I’ve given my gaffer more freedom and flexibility. I feel it’s very important that my gaffer and key grip watch the rehearsals and are not off having coffee. I recommend you hire the best people you possibly can — and then trust them. Also, it goes a long way to say ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ when you ask for something.

Levy: The first thing I do when I get on set is shake the gaffer’s hand and the key grip’s hand, and at the end of the day I do the same thing and thank them for a good day’s work. Working with a gaffer is a delightful dance, one that only the two of you know you’re doing. Sculpting and creating light with a great gaffer is one of the sweetest parts of the job.

Dibie: I always said, ‘I’m like a bird, and my gaffer and key grip are my wings.’ They need to feel they are part of the process.

Cady: I came up as an electrician and a gaffer, and when I first started shooting, I would see the rehearsal, talk with the director about the blocking, and then start putting the lights up in my head, even down to the scrims. A couple years in I realized I was blocking off a huge resource by doing that. Now, I’ll say, ‘This is what we need to do, and I think this might work …’ and the really good technicians will build on that idea. I’ll often say to them, ‘Please let me know if I stop describing my problems and start describing my solutions.’

Bennett: You might be intimidated to hire a really experienced gaffer when you’re on your first or second project, but you need to realize that they are looking for leadership, and when you provide the leadership and collaborate with them, they will fall in behind you and support you with their entire crew, and it will be an amazing experience. On my first job as a cinematographer, I was terrified, and I was smart enough to hire a gaffer who was my dad’s age — he had 20 years’ experience. I said, ‘This is what we need to do.’ It was a great experience, and it helped launch my career, and I worked with him for many years after that. I had the courage to ask him to work with me, and on the occasions when he pulled me aside and said quietly, ‘This is a really bad idea, you might want to do this instead,’ I had the sense to listen to him.

What are some of your insights about working with actors?

Maibaum: I’ll move a light before I move an actor. This business is all about trust. It’s very important that your crew trusts you, your director trusts you and the actors trust you. They’re baring their souls in front of the camera for the audience, and they trust that it’s being recorded in the right way. I recommend you take an acting class if you haven’t already. You’ll have a lot more respect for what actors do.

Bennett: Now that we have really good monitors, directors tend to move farther and farther away from the set, and this is very disconcerting. The actor is standing there in front of the camera, sometimes pouring his guts out, and when the director calls out ‘Cut’ from a tent 200 yards away, the actor looks up and what does he see? Me, the camera operator and the camera assistant, and none of us can give him any feedback on that performance. I’m standing right there, but my concerns are whether the light was right, whether the shot was in focus. If any of you become directors, please work close to the set so that when the actors look up, they see you first.

Moss: I’ve made several films in various capacities with [director] Bruce Beresford. Back when there were no monitors on set, he would stand next to the camera, and now, with so many monitors all over the set that even the caterer occasionally tells you something’s too bright, Bruce still stands next to the camera. People will ask, ‘What about close-ups?’ and he’ll say, ‘I look through my binoculars.’ He’s right there, ready to greet the actors when ‘Cut’ is said and they look up. It’s fabulous. When their eyes first come up, they shouldn’t be looking at a bunch of grips and camera people.