Changing the Face of the Industry — Part III of III

Cinematographers and other motion picture professionals gather to start a process of moving forward. In this third report, we detail the panel discussion “Inspiring the Industry.”

Cinematographers and other motion picture professionals gather to celebrate diversity, inclusion and discussion — and start a process of moving forward. In this third report, we detail the panel “Inspiring the Industry.”

You’ll find Part I of this story here and Part II here.

Event photos by Willie Toledo

In this third segment of the ASC Vision Committee’s day-long event on diversity and inclusion held at the ASC Clubhouse on April 21, an impressive group of motion picture professionals talked about the challenges they face as people of color in the industry. The event, sponsored by Netflix, also featured a keynote address on the research done at the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative (Part I) and a discussion of women in the industry on strategies for gender parity (Part II).

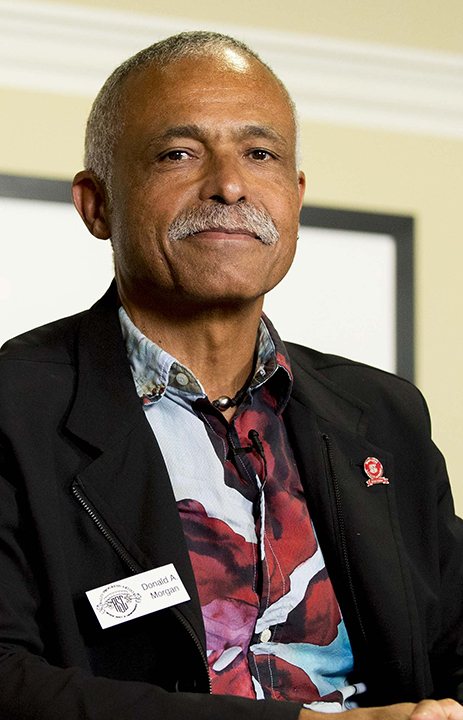

Panelists participating in the day’s ending discussion were camera operator Michelle Crenshaw and cinematographers Eduardo Mayen; Donald A. Morgan, ASC; John Simmons, ASC and Bradford Young, ASC.

“I realized how much movies had turned me and my image of self upside down. It changed my spirit. I knew movies could start a revolution.”

Moderator and American Cinematographer managing editor Jon Witmer asked the panelists what inspired them to enter the business, and everyone spoke about the importance of having mentors early in their careers. Simmons said historian/film director Carlton Moss was his mentor. “He lived with W.E.B. DuBois and was Lena Horne’s manager and wrote The Negro Solider for Frank Capra,” he recalled. “He looked at my photographs and told me that I had the eye of a cinematographer and started sending me copies of American Cinematographer. Then he sent me some film; I looked through the viewfinder and saw the shutter movement and it was all over after that.”

Mayen said he grew up in El Salvador during that country’s long civil war. “We couldn’t go out and play, so movies were the inspiration,” he said. “My dad wouldn’t censor what we saw — he thought what was going on outside was scarier. I fell in love with cinema and began working for a production company, and Rodrigo Prieto [ASC] ended up being my mentor. Watching a professional cinematographer working, first-hand, planted the seed.”

Young recounted how he was expected to follow the family mortuary business, but at Howard University he met Ethiopian filmmaker Haile Gerima: “I signed up for Third World cinema and it was 18 years of unpacking how much American movies impacted me and the notions of my community. I realized how much movies had turned me and my image of self upside down. It changed my spirit. I knew movies could start a revolution.”

Crenshaw grew up in Detroit in a “labor, hands-on hard working environment.” She started shooting and developing still photos when she was 16. “I fell in love with the instant gratification of images that reflected my environment,” she said. “I went to Columbia College, took one film class and was hooked.”

“If you show commitment and passion, eventually someone will take you

under their wing.”

Morgan tried several different jobs before he got one in the mailroom at Los Angeles TV station KTTV. In his spare time, he’d go on stage. “I didn’t understand it, but it seemed like it was fun,” he said. “Then I got to be part of the crew.” He found himself drawn to lighting, and his first mentor was Tom Schamp, a lighting director on Playhouse 90: “We had great conversations about multi-camera lighting, and that was a passion. I started looking at black-and-white movies and wanted to bring more of that look to what I was doing.”

Witmer asked how to find a mentor. “You have to be willing to do work,” said Crenshaw, who also called out Stephen H. Burum, ASC in the audience as another of her mentors. “If you show commitment and passion, eventually someone will take you under their wing. I got in the union in Chicago, and my whole career there was someone willing to support and embrace my passion. When I moved to California, I reached out to Johnny [Simmons]. I was a focus puller on an Isidore Mankofsky [ASC] movie where Johnny was operator.”

“We all have a responsibility to reach back and open our doors and hearts to people who have a passion to do this,” added Simmons. “I kept hearing about Joe Wilcox and Joseph Calloway [who was present at the event], these two black cinematographers, and I finally met them. There have been so many people on whose shoulders I stand, and so many people who presented obstacles that gave me the perseverance to overcome. What you’re looking at on this panel are people who have persevered against obstacles that they couldn’t really complain about.”

“The idea of building community helped me. We built it around the idea of a safe space where you could be a practitioner of your story.”

Simmons told the story of his first day on the job at Dove Films, founded by progressives Cal and Roz Bernstein: “I walk into a grip truck, and I see a grip box covered with derogatory images of black people, Cesar Chavez, Asians. I got out of that truck and called Carlton about this strange situation. He asked, ‘Do you want to be a cinematographer? Do you know any black people doing this?’” He persevered.

Mayen noted that receiving the International Camera Guild’s Emerging Cinematographer Award was crucial in allowing his career to flourish: “It gives loaders and camera assistants a chance to showcase their work and get exposure and more opportunities. That’s a testament to what the union is doing now.”

Young asked if film school is even relevant. “I used to be quite torn about this question,” he said. “I went to film school and it wasn’t always enjoyable. I saw people who didn’t go to film school out in the world making films. Now I’m trying to make a case for community building and a pedagogy of mentorship and inclusion that exist more naturally.”

His first jobs out of school were music videos by film school friends, which is where director Dee Reese found him; the two have worked together since the 2007 short Pariah. “The idea of building community helped me,” Young said. “We built it around the idea of a safe space where you could be a practitioner of your story. Mentorship has that power too; The only place I felt safe was in Haile’s house, or Johnny’s [Simmons] studio.”

“I go to these production meetings and I’m the only [African American] guy sitting at the table. It’s very discouraging; I’d like to see more.”

Stepping outside one’s comfort zone is also important, says Crenshaw. “It’s learning to get along with other people,” she said. “I’ve always wandered and wanted to see what’s on the other side and interact with people. The more you interact culturally with others, it opens up conversation and that can lead you to the next door. I won’t say it’s been easy, but I’ve been surviving as a union member for 30 years.”

Morgan noted how he brought Crenshaw on as camera operator for his award-winning series The Ranch, and thanked Netflix for its support. Mentoring, he said, is an important way to give back. “My dad was in [American Federation of Musicians] Local 47, and I saw the camaraderie among the union musicians,” he recalls.

Witmer asked Morgan and Simmons to describe if the industry today has changed from what it was like when they were starting their careers. “I just finished my fourth pilot in the last two months,” said Morgan. “I go to these production meetings and I’m the only [African American] guy sitting at the table. It’s very discouraging; I’d like to see more.”

Simmons says he had the same experience on-set. “Guys would cover up the lens when I was a PA, they’d hide what they were doing,” he recalled. “But little by little, things are taking a different shape.” He noted that, “there’s a problem of optics in our society. When you think of a cinematographer, do you see Bradford and Rachel [Morrison] immediately? When you think of a director, what picture pops to your mind?” Bias is ingrained and unconscious, he said: “A lot of us think our heads are in one place, and then you take the Harvard University bias test, and it’ll make you feel embarrassed. We have to personally address those biases, consciously and unconsciously, when you select your crew.”

“If you don’t like that cinema isn’t reflecting the culture, then we have to make our own movies.”

Young emphasized that “we are a nation of people who are sick. White supremacy is out there, and those who benefit from white supremacy suffer too. I’m not a healed person. In my community, there are people with real solutions for the post-imperialist, post-slavery black mind. Where are white psychologists writing about the post-imperialist, post-slavery white mind? If you’re white and deny it, your grandchildren will have to deal with it. Same if you’re black.”

New York Times author David Brooks wrote about how “winning a cultural war is more powerful than legislation,” Young added. “The beauty of the previous panel is that people not empowered to talk 30 years ago felt empowered to talk today. If you don’t like that cinema isn’t reflecting the culture, then we have to make our own movies. The art form has the vestiges of white supremacy. This is uncomfortable, but none of us like it. We have to change the conversation, and we can’t legislate it.”

In response to a question from Witmer, Mayen described how he found community in a foreign country after moving to the U.S. “Sleeping on my cousin’s couch, I needed to feel that I wasn’t crazy to be here and that there were others like me striving for the same ideal,” he recalled. “Just hanging out where a lot of filmmakers and people with similar ideas at Mole Richardson and AFI made me feel like I belonged somewhere.”

Crenshaw found community in Los Angeles after making the difficult decision to leave Detroit. “I wanted to challenge myself more,” she said. “I was comfortable there working as a 2nd AC, but there was no room for me to move up. My first experience of Hollywood was working on Home Alone 2 and I fell in love. I met Johnny [Simmons] and did music videos and got into focus pulling. Some of the people I worked with didn’t want to move me up, but I was ready for the next challenge, and here I am 20 years later, making a living as an operator.”

“I’ve taken a lot of shows that I probably would not have wanted to do, but being able to hire people and change peoples’ lives and help families has been a motivating factor.”

Witmer asked the panelists how they create a balance between making a living and choosing projects that “present narratives you can be proud of.”

“That’s a tough call,” said Morgan. “It the opportunity comes up to do a series, you may not like the series, but I’m responsible for 35 to 40 people [being employed], and they all have other people. It’s not just for myself.”

Simmons agreed: “I’ve taken a lot of shows that I probably would not have wanted to do, but being able to hire people and change peoples’ lives and help families has been a motivating factor.” He recalled how, at this year’s ASC Awards ceremony, ASC President Kees van Oostrum asked all the women cinematographers in the room to stand up. He then asked all the cinematographers who are women or people of color to stand. “I would like to acknowledge these people,” Simmons said. “I see cinematographers changing the face of the industry, and taking on the responsibility of making that move to help the new way of viewing us. There are probably more of them here today than I’ve seen gathered in one place — and then years ago, you couldn’t have done that. This is a very precious moment and I’m so glad the ASC is moving in this direction. It’s a big deal.”

One audience member asked about an issue not yet mentioned during the day: Women coming back into the industry after raising children. “We have great skills that translate from what we’ve been doing or from before we left that we’re willing to re-use,” she said. “Are there programs to help us re-enter? How do I get back in the room and make a living again?”

From the audience, Bill Dill, ASC addressed the question: “I say this as someone who is not unfamiliar with the process of starting and trying. The first thing, don’t worry if you’re talented. The world is full of talented bums. Raw, dogged determination is more important. Talent can be corrupted and be a weapon used against you. You’re a cinematographer because you say you’re one. Then go out and prove it. I think that’s all there is to it.”

“You never know how insignificant a moment is to you and how significant it is

to someone else.”

Young added, “This is a wonderful time to be making movies, with Ava DuVernay around. She is my teacher and my collaborator. I was with her when we made Middle of Nowhere for $50,000, without asking anyone to do it for her. From I Will Follow to Middle of Nowhere to Selma, the films she made afforded her to create a space for us. She’s a great example of the answer to the question of ‘What do I do?’ She made her film by any means necessary and made sure it had her imprint. We come to this asking other people give us permission to do something, but don’t expect this industry to hand us anything. They don’t even pass it on to their children.”

“Being a cinematographer is always a state of becoming,” said Simmons. “I tell a lot of people who call me their mentor that even a bad experience on a film is a good experience. From every project I’ve worked on, we grow and learn things we never want to do again. From those early experiences, I realized I could make films, commercials, and so and make it a pleasant experience, rather than being stepped on. We can encourage everyone in the process of making movies and answering studio needs.”

Crenshaw added that “part of that is not being ashamed of who you are. I’m happy to be kind and nurturing. If that’s part of my character and us doing a job together that we both enjoy, more power to us both. And you do learn from your mistakes and that will challenge you to be better. That’s what I take away from all my experiences, pleasant and unpleasant.”

“We all get beat down and lose our confidence and look in the mirror when we brush our teeth and don’t see a cinematographer if we haven’t had a job in awhile,” concludes Simmons. “At a certain point, things begin to go smoothly and you turn into somebody. You can’t forget those days and they make you realize you have to uplift people and create a [welcoming] situation on a crew when a new PA appears. One of those PAs ended up directing five years later and asked me to shoot three commercials. You never know how insignificant a moment is to you and how significant it is to someone else.”

This short video with Young was shot immediately after the event: