Changing the Face of the Industry — Part II of III

Cinematographers and other motion picture professionals gather to start a process of moving forward. In this second report, we detail the panel discussion “Finding Gender Parity Behind the Lens.”

Cinematographers and other motion picture professionals gather to celebrate diversity, inclusion and discussion — and start a process of moving forward. In this second report, we detail the panel “Finding Gender Parity Behind the Lens.”

You’ll find Part I of this story here and Part III here.

Event photos by Willie Toledo

On Saturday, April 21, the American Society of Cinematographers and the ASC Vision Committee hosted a groundbreaking event entitled “Changing the Face of the Industry,” sponsored by Netflix, at the ASC Clubhouse.

Following introductions by ASC president Kees van Oostrum, Vision Committee co-stair John Simmons, ASC and American Cinematographer managing editor Jon Witmer and a key note speech by Dr. Stacy Smith, founder and director of the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative at USC’s Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism where she is also an associate professor, a panel of female entertainment industry veterans discussed the obstacles and solutions related to the paucity of women and people of color working below the line.

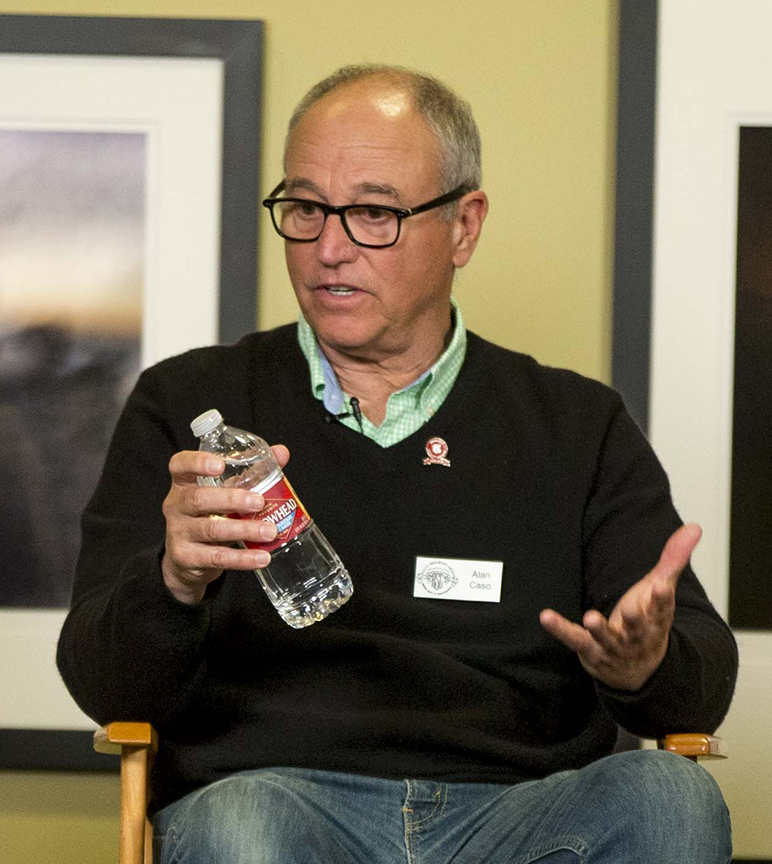

This panel discussion, “Finding Gender Parity Behind the Lens,” moderated Witmer, included Dr. Smith; producer Sarah Caplan; Alan Caso, ASC; Xiomara Comrie, Local 600 national diversity officer; Natasha Foster-Owens, HBO West vice president of production; Local 600 national executive director Rebecca Rhine, and Women in Media founder/director Tema Staig.

“Let’s just get hiring practices to change, so it’s equal opportunity. Once there’s the

opportunity, then they can get their merits.”

The panelists began the conversation by focusing on how the status quo prevents the inclusion of women in cinematography and camera operator positions. “For 40 years, the wisdom has been if we have more women at the top it will trickle down — but it hasn’t happened,” said Staig. “We have to be twice as qualified to get half the respect. If you interview five men, you have to interview five women, otherwise it’s putting too much pressure on that one woman.” She added that, to counter the common excuse that producers can’t find enough women to interview, Women in Media started a crew list, right after the first Women’s March. “We want to make that process [of finding women] as easy as possible,” she said.

Caso pointed out that, “people mix up merit with opportunity. It’s about opportunity, and women of color don’t get them. I’ve done five shows and she’s done one. They’ll hire me because I’ve gained more merits.”

Honored with the Career Achievement in Television prize at the 2018 ASC Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography, Caso made an impassioned acceptance speech that directly addressed issues of inclusion and merit:

During the panel, the veteran cinematographer noted that the International Cinematographers Guild Local 600 was historically exclusionary in years past: “It was very hard to get in and everyone has their story of how they did it. When I think how hard it was for me as a white man to get in, it was impossible for a woman or person of color to get in.”

Years ago, Caso and current ICG President Steven Poster, ASC “had a great victory” by finally getting a woman of color in the union. “She was brilliant and did a great job, but the problem was getting her on the roster,” explained Caso. “The work-around we still have to do to get people their opportunity is ridiculous. Let’s just get hiring practices to change, so it’s equal opportunity. Once there’s the opportunity, then they can get their merits.”

“About 20 percent of producers are women,

so the numbers in the executive ranks

are abysmal.”

An audience member mentioned another old canard: that women aren’t strong enough to carry a camera. “The same thing has been said about firemen, policemen, construction workers and dock workers,” said Rhine. “It’s just code for, ‘We don’t want you to take this job.’ The labor movement is about fairness and equality — it isn’t perfect and needs to do more, but there’s no room in our world for bias, conscious or unconscious.”

Smith observed that, “the mythologizing exists in all these key role — that women can’t open a film, or a black lead can’t open in Asia. All these myths are exactly that. Guilds have to address them, because it affects the whole process. The nomenclature helps support a world of bias — we have to short-circuit it.”

Smith agreed that the idea that inclusion will “trickle down” from the top isn’t entirely accurate. “Top down, bottom up,” is how it must happen, she says. “About 20 percent of producers are women, so the numbers in the executive ranks are abysmal.”

But it’s not just numbers, she said, noting that a woman or person of color can still be part of a paradigm that defers to white male dominance: “I am not letting white men off the hook. The problem is that everyone defers to the same culture. We need people who don’t defer to the same world view.”

Caplan, currently line producer of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, says she’s promoted two female camera operators to become cinematographers. “I now have an electric crew of men of color and an Israeli woman,” she said. “But it’s really hard. We need a program, a way of getting young black men and women to get into these lower echelons so they can rise up [through the ranks].”

Rhine, answering a question from the audience, reported that Local 600 currently has “a number of initiatives, including one that will expand the pipeline and allow us move more people through. The pipeline is part of the problem, but the under-utilization of existing members is also real. We don’t want to pretend the pipeline is the only problem, although we do want to expand that. Local 600 has also committed to unconscious bias training. Money and bodies — we’re committed.”

“Everyone is now coming to us in the union to ask that their voices be heard as well.”

Comrie, Local 600’s first national diversity director, reported that, “there’s been more energy, more interest and a more realistic approach not only to how our membership is comprised but the world they have to work in.”

Initially, the union started by trying to reach out to studio executives, but that generated “very little, if any momentum,” Comrie admitted.

Local 600 also has a long-standing diversity group — led by Donald A. Morgan, ASC — and has created women’s committees in its three regions. The union also supports initiatives to provide education and opportunities for underserved youth, such as the Mobile Film Classroom and Hollywood CPR (see below). “Everyone is now coming to us in the union to ask that their voices be heard as well,” Comrie said, noting that the LGBTQ people want to start their own group.

HBO, explained Foster-Owens, currently rotates cinematographers on the series Insecure and has a single one on the upcoming show Camping, and most of them are women. “I hope these women get more attention,” she said. “For every position at HBO, we’re going to source talent. In that regard, from the ground up, we have a mandate that requires we have PAs trained and brought onto every show. HBO Access provides writing and directing fellowships for women and people of color. We’re training people who otherwise don’t have access points.”

“This speaks to the value of partnerships,” said Rhine. “None of this can do this by ourselves. We need to find people who share our values and move concrete initiatives forward. We can’t fix what we can’t name. It starts with admitting where we are.”

“The problem is that we’re up against this humongous system that is consciously biased against women and people of any ethnicity.

Is there a mandate or legislation that needs

to be in place?”

Caplan addressed unequal pay, noting how problematic and endemic it is. To this issue, Local 600 held “She Negotiates,” a special negotiating training program for women and addressed the systemic reasons why women earn less than men, said Comrie, who reported that, for the second year, the guild will also hold a leadership and effective communications seminar for all members. In regard to unconscious bias training, Comrie says the union is still looking for the right program: “We have a fairly large responsibility to promote this. And we have a great opportunity to affect people out there who are working.”

Smith said that, “collective action happens when you get all the key stakeholders in a room and negotiate to change the rules. Networks, studios, production companies… all those people need to come to the table and admit they have a systemic issue and put up the resources for it to happen. Otherwise the guilds will be hitting their heads against a wall.”

To create a “willingness and leverage for that to happen,” said Rhine, only half-joking, “I’m a big fan of public shaming.”

One audience member noted that director Ava DuVernay has “pushed a lot of women” through her TV show Queen Sugar. “The problem is that we’re up against this humongous system that is consciously biased against women and people of any ethnicity. Is there a mandate or legislation that needs to be in place?”

Attending the event as a member of the audience, ICG President Steven Poster addressed this question himself, noting that when he became a member of ASC in 1987, there was only one active female member of the Society. That cinematographer was Brianne Murphy. Since then, Poster said, there has been a steady increase in women and people of color among ASC membership: “But there is a lot of work to be done before there isn’t a [ethnicity or gender] descriptor in front of the title ‘cinematographer.’”

Also from the audience, ASC Vision Committee co-chair Simmons agreed with Poster. “We department heads — cinematographers, key grips, art directors — need to be able to change the appearance of our crew and hire people who represent our society at large,” he said. “We like to work with the same crew all the time because expediency is so important. But we have to hire different people, and have to personally take the responsibility of changing our crews — then that picture becomes contagious. So that, when a young person walks on set, they see the possibility of their dream.”

“You never know who’s watching you. In your own ranks, you can help promote people. Once you spread yourself through the industry, you will all be working.”

Power, noted Rhine, is “never given up voluntarily. If ever there was a time for more access and opportunity for more new voices, this is it. We can’t let it pass.”

“Let’s build on perseverance,” continued Simmons. “It can be so demoralizing to keep running up against prejudice.” He then asked Caplan and Foster-Owens how they persevered and achieved their positions.

Foster-Owens credited her parents: “They taught me to have pride in myself and to ensure I’m not the only person at the table. I continue to meet people whether or not I have the chance to hire them. There is value in mentoring people and ensuring you’re consistently learning from each other.”

Caplan spoke of how, early in her career, she sat down every day and called two people “and sometimes got to meet them. Then, I’d always ask, ‘Do you know anyone I can call? Can I use your name?’” she remembers. “I had amazing experiences and just kept going.”

Networking works, Caplan emphasized, inviting every person of color at the event to network with her. “Even if you’re doing a job that’s not that interesting, you’re meeting people who can end up being important in your career,” she said. “You never know who’s watching you. In your own ranks, you can help promote people. Once you spread yourself through the industry, you will all be working.”

You'll find Part I of this story here.

Organizations Making A Difference

Creating opportunities where there were few to be had, these three entities are also looking for volunteers and sponsorship.

Hollywood CPR is a non-profit entertainment artists, crafts and technicians training program that was founded in 1997 by Kevin Considine with the goal to get under-represented people into entry-level jobs. The group, which has a partnership with West Los Angeles College, many local high schools and organizations, has graduated more than 400 people — all of who are eligible for the roster. Vice president Laura Peterson notes that training program is “rugged,” that meaning graduates are ready to work.

Inner City Filmmakers was established in 1993 and provides free, year-round, pre-professional, hands-on training and job placement for diverse disadvantaged Los Angeles County high school graduates aged 17 to 23. Of its 650 alumni, 100% are high school graduates and working in various fields; 99% are scholarship students at various colleges and universities, and more than 68% have been matched to industry jobs.

Mobile Film Classroom is a production studio on wheels that travels throughout Los Angeles County to bring digital media instruction to underserved and at-risk youth. One of its signature programs is the “Filmmakers Boot Camp,” which consists of 12 interactive classes that guide students through the creative production process to a final product. The first Mobile Film Classroom vehicle hit the road in 2006; it has since worked with over 60 Southern California school districts, charter schools, juvenile justice centers and community-based organizations.

Next in this report:

Part III: “Inspiring the Industry,” a panel discussion with camera operator Michelle Crenshaw; cinematographer Eduardo Mayen; Donald A. Morgan, ASC; John Simmons, ASC and Bradford Young, ASC.