Frederick Elmes, ASC Honored by AFI

The American Film Institute presents Frederick Elmes, ASC with their 27th annual Franklin J. Schaffner Alumni Medal.

The renowned director of photography is bestowed the American Film Institute’s Franklin J. Schaffner Alumni Medal.

By Lauretta Prevost

Franklin James Schaffner made a career as a film and television director, winning four Emmys for TV work and bringing home an Academy Award for the feature film Patton. The American Film Institute annually presents a medal in his honor, selecting from alumni of the AFI Conservatory or the AFI Conservatory Directing Workshop for Women a filmmaker who embodies Schaffner’s dedication, talent, taste and commitment to quality filmmaking. For 2017, at the 45th annual AFI Life Achievement Award Gala held on June 8, Frederick Elmes, ASC received this recognition.

Elmes has worked with such directors as John Cassavetes, Jim Jarmusch, Ang Lee, David Lynch, Mira Nair and John Turturro. His other honors include National Film Critics, New York Film Critics Circle and Sitges Film Festival awards for his cinematography in Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), Independent Spirit Awards for Best Cinematography for his work in Lynch’s Wild At Heart (1990) and Jarmusch’s Night On Earth (1991), and an Emmy nomination for director Christopher Reeve’s In The Gloaming (1997; see AC Oct., ’97). In 2000, Elmes and Lynch were honored together by the Camerimage Film Festival for their longstanding collaboration, which also includes Eraserhead and Dune (shooting second unit).

Elmes graduated from the AFI in 1972, a time when the conservatory program was still in its infancy, and he considers his time there to have had a strong impact on his filmmaking career. “We were a disparate and talented group of fellows exposed to each other and to real in-depth cinema storytelling,” he recalls. “The program was small and concentrated, and there were just a handful of cinematographers in service to the fellows, in order to get their films shot.”

During his time at the AFI, Elmes formed a relationship with filmmaker-in-residence instructor John Cassavetes, who offered him the role of cinematographer on The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976). “It was a great experience to shoot a real feature film with professional actors and a talented maverick director,” Elmes reflects. “It was a fabulous experience for a young novice.”

Elmes’ other early feature was Eraserhead (1977), a surrealist horror film helmed by David Lynch. The AFI served as the meeting ground for Elmes and Lynch, and over the years it took to shoot Eraserhead their relationship cemented; they would go on to work together on Blue Velvet (see AC Nov. 1986) and Wild At Heart, the latter garnering a Cannes Palme d’Or in 1990.

On Eraserhead, Lynch’s directing style was specific and controlled, with an intense attention to detail. In contrast, Cassavetes’ approach to The Killing of a Chinese Bookie was full of improvisation and spontaneity. Developing under the distinct directorial styles of these two icons of independent cinema influenced Elmes’ approach to his craft for decades to come, and set the stage for the cinematographer’s journey of ongoing working relationships with a variety of directors.

Elmes’ career is in large part defined by talented directors repeatedly seeking him out. Lynch, Jim Jarmusch, and Ang Lee have each collaborated with Elmes on at least three feature projects. “Relationships with directors are all about being able to get along and being compatible,” Elmes reflects. “The filmmaking becomes a flowing, mutually creative process. There becomes an ease of being together. ”

Elmes believes his basic approach to filmmaking has remained steady throughout his career. “My ability to communicate has gotten a little better over the years and I’m able to work with directors and others more clearly and quickly, but the process — the unfolding of a story and visualizing it with a director — is still basically the same. It’s about the shared exploration on a detailed level of characters, how we unravel the story, and how we make it visually powerful.”

Ang Lee reflects on the creative conversations he and Elmes shared during preproduction on their projects: “That’s the most precious thing about Fred — I spent most of my time with him talking about drama and the human condition, and left the aesthetics to his capable hands and artistry.”

"Fred achieves a kind of magic in low light, which is what I needed for The Ice Storm,” Lee continues. “As I worked with him, I came to realize that Fred’s magic was actually about reaching down to the very limits of low exposure and using a combination of different color gels. The chemistry between them is wonderfully toxic, as if the image were coated with opium. There is an enchanted beauty in that soft shadow of his, something that I don’t know how to duplicate. There’s one shot, just after the power goes off in the ice storm, of a cut glass key bowl that’s just pure artistry. And the end of the movie is full of reflections and transparent subjects—mirrors, glasses and ice — that thanks to Fred, really capture the transparent fragility of life and emotion itself.”

Early in his life, Elmes studied photography and film at the Rochester Institute of Technology, where he also focused on art history, drawing, and graphic design while shooting short films. It was attending New York University’s graduate film program and receiving the mentorship of Czech cinematographer Beda Batka that Elmes considers a significant turning point. “What I learned from Beta is that what the camera does makes a big impact on what happens with the story of the film,” Elmes reflects. “It’s not just about getting exposure right and the image in focus. We’re doing a whole lot more with the camera to help reveal the character.”

In addition to his studies under Batka, Elmes considers a powerful inspiration to be the work of Sven Nykvist, ASC — known for his prolific career and collaborations with Ingmar Bergman, and revered by many for his natural lighting and precise composition. Another influence Elmes appreciates is cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo, known, in addition to his neorealism and cinematic skill, for the rapport he was able to establish with directors, and his intuitive sense for visually interpreting the director’s vision.

“Cinematography is a great creative outlet,” Elmes muses as he reflects on what keeps him engaged in the craft. “It’s wonderfully challenging, and every project is quite different because of the story and the chemistry of the people involved. It’s new and fresh each time. There is the challenge of finding a new way to do the job on each project, how to approach telling each story, how to tailor the approach to the director. It’s a lot of fun.”

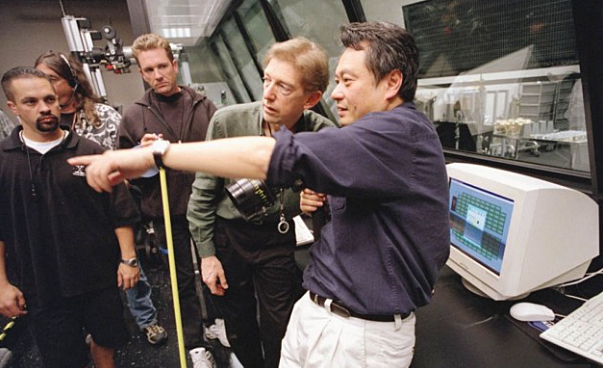

Elmes isn’t overly concerned with genre. For him the focus is delving into each particular script, and with the director determining how to tell that story in an engaging way. Directors seek him out across genres: Ang Lee and Elmes have worked together on the drama The Ice Storm adapted from the novel of the same name; the Civil War drama Ride with the Devil and the superhero/mystery Hulk. (See coverage in AC Oct., 1997; AC Nov., ’99 and AC July, 2003.)

“After The Ice Storm, I worked with Fred on Ride with the Devil,” Lee reflects, “where he achieved a different, classy look, especially in the candle and campfire lit scenes. We then shot a BMW short film/commercial together, whose mesmerizing night scene had a real feeling of enchantment. And finally, on Hulk, Fred managed to make a big movie look intimate, which is exactly what I wanted.”

Over the years, Elmes believes he has benefitted a great deal from those who had more experience than he: “Many were very free with their knowledge and helped guide me as a I grew and matured as a filmmaker, and I have enjoyed sharing what I know with others as well.”

In 2016, Elmes taught a graduate level course on advanced cinematography at NYU. He has led Master Class sessions for the American Society of Cinematographers in Toronto and Beijing, and he has given cinematography courses the world over, such as for Tel Aviv University and for organizations in Thailand. “I’ve given many of these courses,” he shares. “I find them satisfying because they are an opportunity to meet young filmmakers and learn a little bit from them.”

I was introduced to Elmes through a mentorship program with the Independent Film Project (IFP) when we were matched as mentor and mentee. Years later, he remains generous with his time. I call him up when I have a new challenge, such as the first time I shot on an Alexa camera. His advice tends to bring me back to the bigger picture: we discussed proper exposure and technical considerations, and he ended the conversation by sincerely reminding me that a main thing to remember about filmmaking is that the director has had a lot more time with the material and usually knows what they are talking about: the director is usually right.

When not on set, Elmes finds continued inspiration by going to the movies, visiting museums, and exploring still photography. When asked if he believes filmmaking can change the world, he pauses. “Ultimately we’re making entertainment. We’re making things that move people and affect them emotionally, and perhaps make people think about things in a new way. Filmmaking is a great endeavor that can make a little bit of difference.”

Elmes believes that cinematography will become increasingly adventures and fluid. “Look at the visual styles of the films last year; from Moonlight to Arrival, from Mommy to The Lobster,” he reflects. “These are all interesting stories told in very different ways with the camera. With new equipment that is smaller, lighter and more flexible, we will continue to push the limits of moviemaking.”

Lynch won the Franklin J. Schaffner Alumni Medal in 1991, and other past recipients include directors Patti Jenkins, Terrence Malick and Darren Aronofsky, as well as ASC members Caleb Deschanel and Wally Pfister. “Fred Elmes really deserves all the attention and celebration that he’s getting,” Lee praises. “He’s an incredible artist, and I cherish the time I’ve spent working with him.”