A Cinematographer’s Space Odyssey

Following her historic Fram2 orbital mission, astronaut Jannicke Mikkelsen, FNF visits the ASC Clubhouse to discuss shooting in orbit.

Event photos by Danyael Miguel

Just one week after returning to Earth from a near-four-day human-spaceflight mission, Norwegian cinematographer and director Jannicke Mikkelsen, FNF visited the ASC Clubhouse to share her experience as a crewmember for the historic expedition. Her first public presentation on the mission, sponsored by Red Digital Cinema, was delivered on April 11 to a large and captivated crowd of Society members, colleagues and friends, who laughed heartily when one of the event’s organizers — Suki Medenčević, ASC, ASBiH, SAS — introduced himself as “the co-chair of the ASC Interstellar Committee, formerly known as the ASC International Committee.”

Named Fram2 — in homage to the Norwegian polar-exploration ship Fram, which completed trips to the North and South Pole in the late 1800s and early 1900s — the mission was operated by SpaceX with a Crew Dragon spacecraft, and was the first of its kind to explore Earth from a polar orbit. Joining three other crewmembers — mission commander Chun Wang, vehicle pilot Rabea Rogge and mission specialist and medical officer Eric Philips — Mikkelsen served as Fram2’s vehicle commander, and was responsible for documenting all activities within the craft, including their observation of atmospheric optical phenomena.

Mikkelsen’s role in this endeavor may well have been written in the stars.

Driven by an early yearning to become an astronaut, she made a phone call to NASA to apply for a job involving 3D landscape mapping at 12 years old, and managed to advance to the next round of the interview process before her mother informed the agency of her age. Mikkelsen noted it was around this time that she began studying the NASA space shuttle mission STS-99, “which was mapping the world into 3D. That was the coolest thing I’d ever seen, and that put me on my career path to become a cinematographer, specializing in virtual reality and 360, and combining that with virtual production and anything new on the edge of what digital technology can achieve.”

As she built up a body of work, Mikkelsen came to collaborate with David Attenborough as a camera operator on the underwater 360-degree documentary miniseries The Great Barrier Reef for BBC. She then directed the 360-degree immersive Queen concert VR The Champions — a project on which she worked closely with Brian May, the band’s guitarist and an astrophysicist who helped bring her into the greater NASA community. She later co-founded the production company O2XR with her fiancé, Rolf Harald-Haugen, to focus on shooting in polar climates and other hazardous environments — an objective that naturally broadened in scope when the cinematographer was given the opportunity to join Fram2. “Now, we are probably going to focus all of our attention on filmmaking in space and helping future filmmakers work in space,” she said.

Entering orbit upon Fram2’s successful launch on March 31, Mikkelsen’s chief cinematographic concerns were to deliver visual representations of waves in the upper-Earth atmosphere when flying over auroras en route to the North and South Poles, and to capture a range of resonant moments that might entertain and inspire viewers. Her cameras of choice to cover the mission included the Red V-Raptor 8K VV and the Canon R5 C.

“I needed cameras that would both work with the same lens set,” Mikkelsen said. “And I needed lenses that would sustain their quality, so [during testing], they were subjected to six Gs over 11 minutes and were blasted with radiation, heat, cold and humidity. This was pretty much the same testing we went through as humans [to qualify for spaceflight].

“There were other things during testing that you don’t normally take into consideration — like the electrical arcing from battery to camera body,” she continued. “[In space,] the electricity travels on the outside of the body instead of the inside. And it’s difficult to find camera mounts nowadays that don’t have a battery or some sort of lubricants or fluids. So, I spent much of my time trying to find mechanical ball heads and attachments, because I couldn’t have anything that could become a foreign object to breathe. If an O ring floated away, or if screws came loose, that would be a danger for us in the crew, because those things could end up in a vent. In the Dragon capsule, I was relying on constant air circulation, because without it, the C02 that I breathe out would just bubble in front of my face and I would suffocate. So, our choices of camera equipment were very important to keep us humans alive.”

O2XR CTO Ron Martin and virtual production supervisor Habib Zargarpour were also on hand to discuss their 14-month prep period for shooting the mission, which involved extensive previs sessions detailing each shot the cinematographer planned to capture in space by employing virtual mockups of the Dragon, as well as renderings of her desired cameras and lenses. “In a version of the iPad app we developed for Yannicke, you could select which sensor size you’re using, which camera, which lens, and the clothing the astronauts would be wearing,” Zargarpour said. “And the most complicated thing was the orbit itself: There’s an orbit happening every 90 minutes, the Earth is spinning, and then you have the cupola, which has to face the sun. It was great to watch Yannicke navigate the previs system and determine what kind of things she’d need to look out for.”

“It was an amazing opportunity to work on a production where someone is trying something new — going into space — and taking the gear that you’ve helped curate in previs to subject it to painful tests,” added Martin. “It’s almost hurtful to hand over a piece of equipment when you know they’re going to put it under six Gs of biotesting and take it from minus-10 Celsius to plus-40 Celsius. We just had to hope that everything we chose was going to pass those tests. When interfacing with manufacturers to determine what types of technologies were used to build the tools that Yannicke would rely on in space, everyone within the community was so forthcoming to help on her mission.”

At the time of her presentation, Mikkelsen could not yet share the footage she captured, as it remains under the supervision of SpaceX and the U.S. Space Force until it is cleared for commercial use. She did, however, wish to detail some indelible scenes she witnessed unfold while observing Earth during nighttime.

“During the daytime, you don’t see life on Earth,” she said. “It’s colorful; the oceans are turquoise, and it looks like paradise, and then you see the thin blue atmosphere protecting us. But at nighttime, the planet just glows in artificial light; it looks like a glow-in-the-dark spider or something. When looking over the biggest cities, I thought my cameras had broken. Autofocus doesn’t really work in space, so I thought my cameras were out of focus, but it turned out to just be pollution; I couldn’t get the cities any sharper. I also thought at one point that I was seeing stars and galaxies, but it was the Earth’s oceans filled with fishing boats. Then, looking at the north of Russia, parts of Asia, Africa, North Korea… it all looked like ocean, completely dark. So, I realized that what I was looking at was the dispersity of wealth: Light and electricity meant wealth, and there were a billion people living in these dark places that I couldn’t see from space.

“Planet Earth, I was always told, looks very peaceful from space. But on day two, I was looking at and filming Europe, and suddenly I saw a glowing ball that looked like a rocket. It was weird: ‘What’s going on?’ I thought, ‘Okay, this is a meteorite.’ And I saw it go through the atmosphere, but I didn’t see a burn-up. And then I saw the clouds light up underneath in orange and yellow. I then realized, ‘That’s Russia, and that’s Ukraine.’ I was watching a missile attack.”

In her closing remarks, Mikkelsen considered her sense of place within the world of cinematography from a global perspective. Since returning home, “I started looking at Earth as an ant hill,” she said. “It’s as if the smartest ants on that ant hill just slung four of us ants into orbit. And an ant doesn’t know its purpose, but it’s a very important part of our ecosystem. The ASC has always looked after me — you’ve been my mentors and have helped guide me through my career — and it’s incredible to feel the warmth of the international artist community come together to support what we’re creating. But as humankind, working together, developing technology, we don’t always know where we’re going or what the next step is. Yet, we are driven by our fascination with technology. I can’t say what is the ‘purpose of it all,’ but I think we are on the right path.”

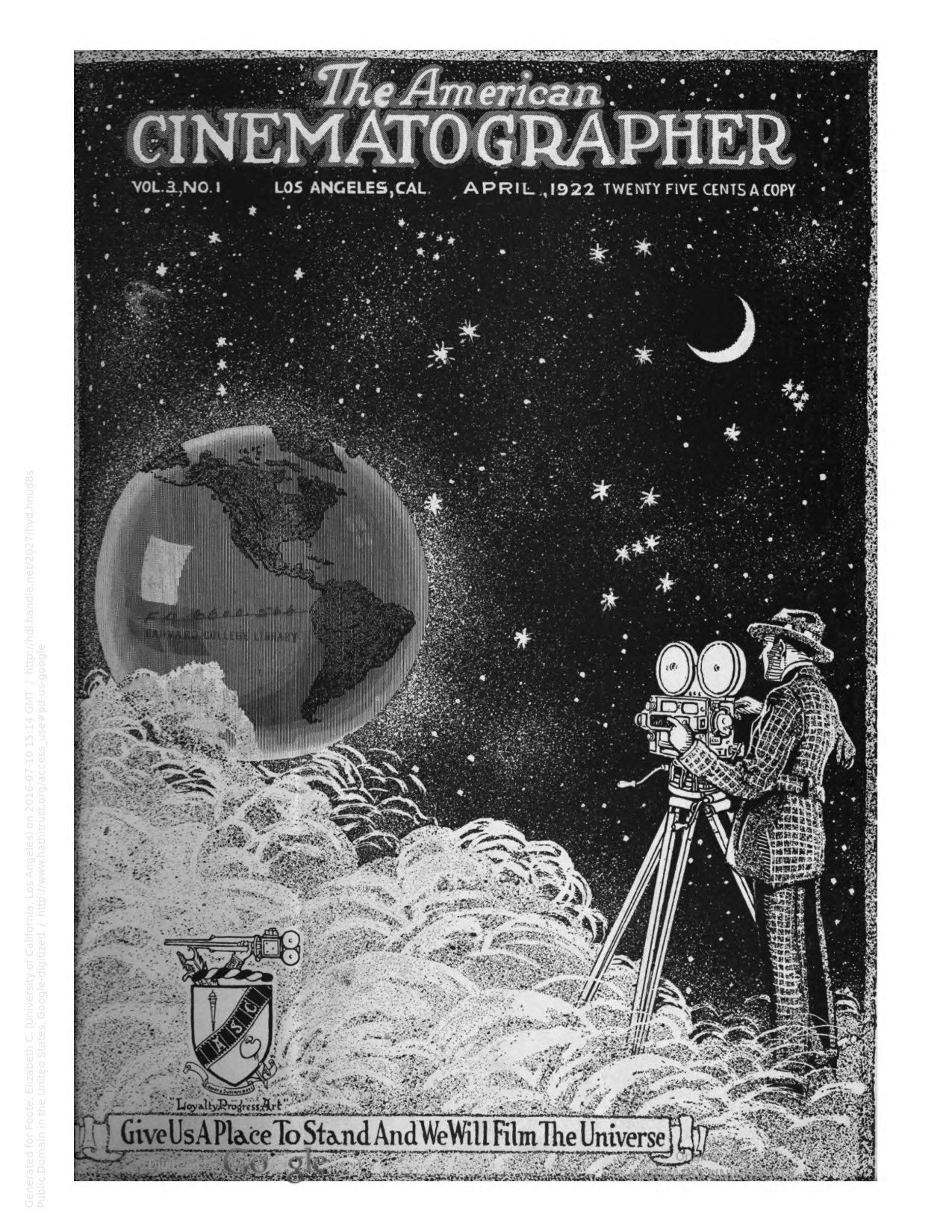

Some AC readers will remember this classic cover depicting cinematographer in space, illustrated by Lewis Physioc, ASC and published in November of 1922 with the headline “Give Us a Place to Stand and We Will Film the Universe”: