In Memoriam: Giuseppe Rotunno, ASC, AIC (1923-2021)

One of the masters of modern cinematography, the Italian director of photography died on February 7 at the age of 97, leaving behind a body of influential work that will continue to resonate.

Rotunno spent nearly 60 years behind the camera, capturing beautiful and mind-boggling imagery dreamed up by the world’s greatest directors. Although he collaborated with many top American filmmakers, including Orson Welles, John Huston, Stanley Kramer, Robert Altman, Bob Fosse and Mike Nichols, he will be best-remembered for his multiple collaborations with the brightest lights of the Italian cinema: Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti and Federico Fellini.

“You know, I am just one of the people who has worked with those great directors,” Rotunno told American Cinematographer when he was honored for his artistic contributions to cinema history with the ASC International Award in 1999. “At the moment, I am the star, and I’m very proud to be talking about working with them,” he described to AC contributor Ron Magid. “De Sica, Visconti and Fellini always put very different and unique moods into their films; they were also different in terms of [their approach to] the acting, the makeup, and everything else. I simply tried to follow all of those things with my light, and put them in the best condition to be received by the audience. It’s very difficult to explain my work, but it’s like being a painter. I think painters feel something inside through the paints and the brush as they put their ideas on a on a canvas. That is also what I do.”

Although Rotunno received many honors during the course of his career, including a 1980 Academy Award nomination for All That Jazz, directed by Bob Fosse, he said that he was particularly proud to accept the ASC’s International Award: “This honor means a great deal to me, because it comes from my colleagues, whom I hold in very high regard.”

Born on March 19, 1923, in Rome, Rotunno started out from very humble beginnings. As a boy, he never entertained ideas of going into the film business; it was the death of his father, when Giuseppe was just 17, that prompted him to seek work anywhere he could find it during the difficult pre-war days of 1940. Thankfully for audiences everywhere, the gods steered the young Roman to the doors of Cinecitta Studios, where he landed the only available opening: a job helping out in the studio’s photography lab, which was run by the three Bragaglia brothers, who were famous for having researched and invented “photodynamism.”

One of the brothers, Arturo, recognized the young man’s talent and gave him a Leica still camera to experiment with on his days off. “On Saturdays and Sundays, I started to make some photographs of my own,” Rotunno remembered. “Then, on Monday, Arturo gave me permission to bring in my photos. I got deeply into the photo department, accumulating more knowledge. I started to learn about what was happening with the light, the film, and other things, and I began to love it. It soon became part of my life.”

“I was able to create a wonderful harmony with my directors, and to release their fantasies.”

Within 18 months, Rotunno graduated from developing pictures in the studio’s darkroom to becoming an on-set still photographer at Cinecitta. ‘‘Arturo, who was actually the chief of the photography lab, helped me move to the camera department, because he felt it was important for me. I became a camera assistant.” The young man soon found, however, that working as an assistant at the busy studio was akin to being a glorified manual laborer. “I did all of the work in the camera department,” Rotunno said. “I just cleaned up the camera, loaded the camera, or put it in a box.”

Nevertheless, the experience paid off; by the early 1940s, Rotunno was serving as a camera assistant and operator. Meanwhile, he was also getting his first experience as a director of photography by working on documentaries, which were all the rage in Italy at the time. Before breaking into dramatic features, future directorial giants such as Visconti and Michelangelo Antonioni were making 10-minute short subjects for theaters. Rotunno shot some 10 documentaries for Michele Gandin, the director he considered the best in the field. While most everything he shot was black-and-white, Rotunno’s first color film with Gandin anticipated his later stylized work with Italy’s cinematic masters: “We shot in a village in southern Italy, where the old houses were painted bright white and all of the women dressed in black. So it really was a black-and-white film — but in color!”

Rotunno earned one of his first big breaks while working as an operator on Roberto Rossellini’s World War I drama The Man With the Cross. “It was 1942, and the first time I really put my eye to the camera’s viewfinder,” he said. “I was operating one of three or four cameras while we were shooting a night battle scene, from inside a Russian house that had a big hole in the wall made by a cannon shell. Even though our set was an ‘interior’ it was actually built outside. Because the battle covered such a large area, we could not shoot it ‘night-for-night’ so we were shooting ‘day-for-night.’ Unfortunately, it was a sunny day, and the contrast between the interior and the exterior was impossible. I had to make it even, so I sandwiched a red and green gel between two big pieces of glass, creating a ‘filter’ that we placed over the hole. After that, Rossellini started to talk to me, and began giving me a little more importance at work.”

Before he could make any more headway in his homeland’s film industry, Rotunno was drafted into the military during the darkest days of World War II, serving as a combat photographer in the Italian army’s film unit. Suddenly, the battles he was shooting were all too real. “I was in the service, shooting alongside reporters, from 1942 until April 11, 1945,” Rotunno said. “That’s when I was liberated by the American Army in Germany, where I was a prisoner. I never left my work, from the beginning of my career until now.”

Landing a job in Italy was much harder after the war, however. Although Rotunno returned to Rome in September of 1945, it wasn’t until 1948 that he was able to pick up where he had left off. “I started again as a camera assistant, made a little salary, and occasionally worked as a camera operator — very occasionally,” he noted wryly.

One of Rotunno’s first jobs after the war was a stint on Henry King’s epic Prince of Foxes (1949), starring Tyrone Power and Orson Welles. The film was photographed by the great Leon Shamroy, ASC, who recognized the star quality in the young camera assistant he had hired. “I got on very well with Leon, the man who put me on the camera again,” Rotunno reflected. “The shoot was very long, and we worked very closely together. It was my first chance to work on a big production, and it was a spectacular film. I had never seen something so complicated for a cameraman: battles, exteriors, night stuff, many things. Shamroy was really admired by all of the artists there; he could light so beautifully. He was also a great man with a big heart, and he gave me the opportunity to stay close to him and watch everything he was doing. That set, for me, was really a university; I relied on my eyes and my ears to pay attention to what was happening around me.”

Rotunno was soon back on track, working as a camera operator. During this time, Rotunno amassed more technical knowledge while working on at least 25 films. He recalls, “They often used more than one camera — in fact, they used three cameras sometimes. They would put me by a camera and say, ‘Stay there!’” One of these pictures was the sword-and-sandal epic Attila the Hun (1954), co-starring Anthony Quinn and Sophia Loren, and photographed by the famed Aldo Tonti. The other two operators on this picture were future ASC fellows Karl Struss and Luciano Trasatti, both of whom also became famed cinematographers in later years.

Sadly, it was a tragedy that propelled Rotunno to prominence as a director of photography. He was operating for revered cinematographer Aldo Graziati on Visconti’s Senso, and in November of 1953, near the end of production, the company moved from Verona to Venice. Meanwhile, Rotunno went to Rome to discuss L’Oro di Napoli, Graziati’s upcoming collaboration with De Sica. There, he received word that Graziati had been killed. in a car accident. Devastated, Rotunno returned to Senso, and production resumed for a time with British cinematographer Robert Krasker, BSC. When Visconti and the Englishman failed to click, the director asked Rotunno to take over as director of photography.

Because of Graziati’s death and other factors, De Sica’s L’Oro di Napoli remained an unrealized project for Rotunno, but in 1955, the director remembered Graziati’s talented camera operator when he was preparing to shoot Pane, Amore e ... (Scandal in Sorrento), which would star Sophia Loren and De Sica himself. While Dino Risi is the film’s credited director, Rotunno recalls that De Sica controlled the production. The 30-year-old Rotunno’s first major film as a cinematographer was especially demanding because it was shot almost entirely on location. The project was also one of the first CinemaScope productions in Italy.

To prepare, Rotunno traveled to London to observe production of the Anatole Litvak CinemaScope romance The Deep Blue Sea, which was photographed by Jack Hildyard, BSC. The experience helped Rotunno immeasurably when shooting commenced on Scandal in Sorrento, although the challenges were considerably different on De Sica’s seaside, location-based romantic comedy. “Because we were shooting in CinemaScope, and due to the quality of the film stocks at the time, it was very difficult to balance our interiors against the bright light of the ocean exterior,” Rotunno remembered. “After all, we’re talking about 43 years ago.”

But Rotunno’s years of experience working with De Sica (he had also served as camera operator on Umberto D and Terminal Station) made his transition to director of photography a smooth one, and his success with the difficult CinemaScope production attracted the attention of one of the world’s greatest directors. “I prepared a film with Orson Welles as director, but it never started,” Rotunno lamented. “We had many meetings for a film called Operation Cinderella, and we also looked for actors and locations. We had even found some adequate solutions for the photography. But at a certain point, Orson quit and the picture was never made. Nevertheless, I had enough time to get to know him, talk to him, and ‘steal’ some ideas from him. He told me he always liked to place the camera at a low angle; because he had also directed in the theater, where the stage is higher than the floor, his point of view was always from the floor looking up at the actors. It was really a shame for me that our lost production was never ‘found’ again.”

During that same year, 1955, Rotunno shot The Monte Carlo Story, which again starred De Sica, this time alongside the great Marlene Dietrich. The picture was the first directorial effort by the fine screenwriter Samuel Taylor, but once again, De Sica controlled the reins. Although Rotunno shot the film in yet another unfamiliar widescreen format, Technirama, his greatest challenge was the temperamental Dietrich herself, who was then in her late fifties and fearful that the camera would show her age. Dietrich had been absent from the screen for some time, and the lighting technology had changed, which made her nervous. Rotunno recalled, “When she could not feel the warmth of the light on her face, she believed that she wasn’t getting enough light. To gain her confidence, I did some tests alone with her before we started shooting. I tried for a simple crosslight on her face, because she needed it then. When I showed her the tests, she was very happy, and she made big publicity for me; she said, ‘He is a genius!’ Then everybody looked for the genius. Fortunately, my wife says I was very thin at the time, and not bad-looking!”

Rotunno quickly developed a reputation as a master photographer of the world’s most beautiful women with films such as The Naked Maja (1959) and Five Branded Women (1960). “I worked with Ava Gardner, Sophia Loren, Gina Lollabrigida, and many others,” Rotunno said. “I was very, very lucky. It’s really a pleasure to light those kinds of faces. To start off, I always set up three lights so I could ‘understand’ their faces. The lady would be in front of the camera, and I would place one light behind the camera, another light exactly across my right and one on my left. Then I would see how the actresses’ movements changed the light, and adjust my lights for them. I always use my eyes and my aesthetic taste to judge what is good or not good.”

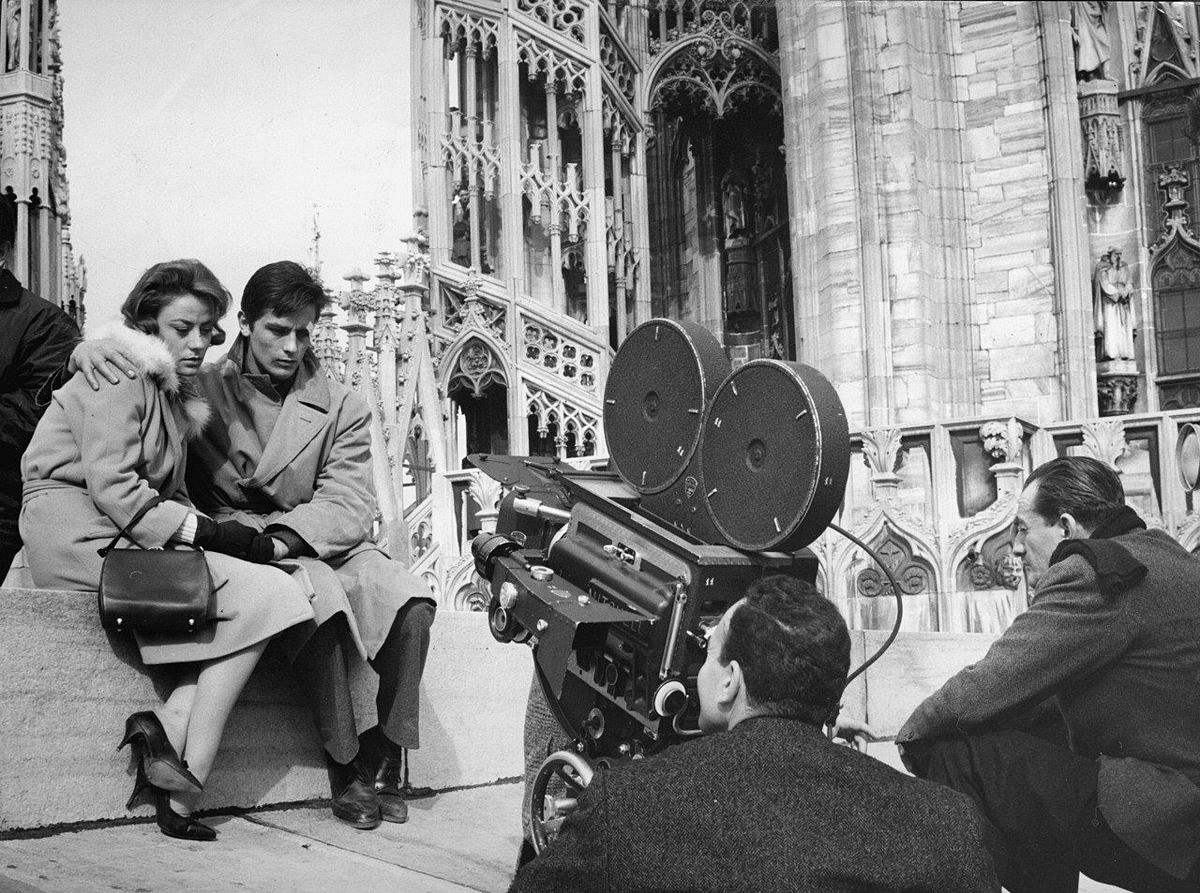

In 1963, Rotunno teamed with De Sica once again on the classic Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, which went on to win the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. The film starred Loren and Marcello Mastroianni in three separate tales, each of which depicted women using their sexuality to get what they wanted. Perhaps the most difficult sequence was one that took place almost entirely inside a Rolls Royce driving through Milan. Rather than shoot in the studio using process photography, Rotunno devised a clever method of filming the entire episode on location. “We built a fake Rolls Royce body and put it on this long, low truck with a platform used to transport boxcars to the train;’ he explained. “In front there was the camera car with a crane and lights all over it, plus a fog machine. We shot the scene in real time, and you could see the location outside the windows as the car passed through the city.”

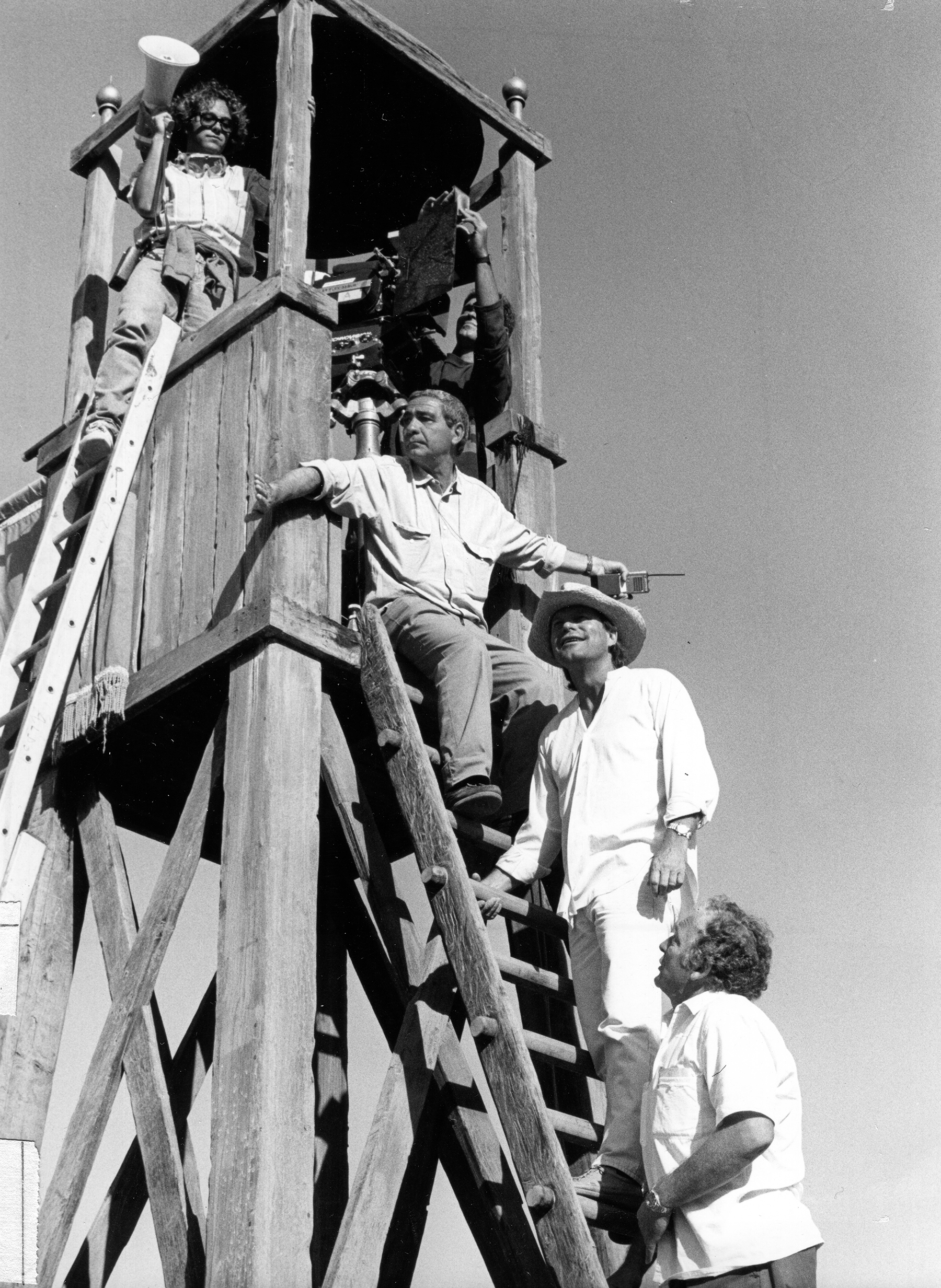

Following Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, Rotunno photographed his most epic production to date: John Huston’s The Bible (1964), which was filmed in the Dimension 150 65mm format. He then worked on the anthology film The Witches (1966), shooting all of its three segments for directors Visconti, De Sica and Pier Paolo Pasolini. Working for such a trio of perfectionist taskmasters — on one film — was quite an experience. “I can tell you that all three directors tried to be as honest as possible with audiences,” Rotunno said. “However, they had different backgrounds, sensibilities, tastes and points of view, so those films were really different.”

Rotunno’s final film with De Sica was The Sunflower (1969), but the two men remained friends until the latter’s death in 1974. “I still have a relationship with his daughter,” Rotunno said. “I knew Vittorio very well, and we worked with complete freedom. It was fantastic.”

Both before and after his lengthy collaboration with De Sica, Rotunno had also forged a strong artistic bond with Luchino Visconti. “In certain ways, Visconti was my father in my job,” Rotunno said. “I did many films with him from 1951 on, first as a camera operator, and later as a director of photography. I had that relationship for work, for life, forever.”

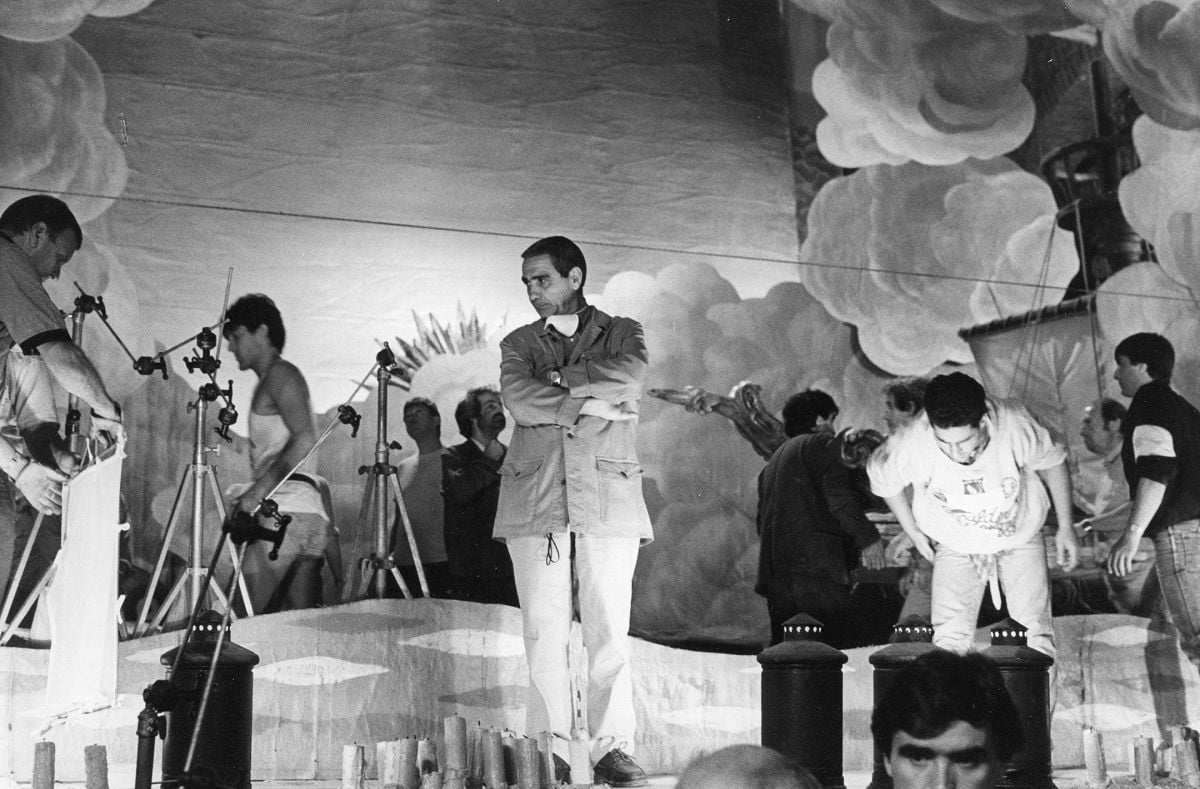

Rotunno’s first solo effort for Visconti was White Nights (1957), an elaborately plotted love story based on Dostoyevsky’s novel. His blackand-white photography enhanced both the reality and artificiality of the film, which marked Visconti’s transition away from neorealism. “We shot everything on stage, where we built a section of the city with the canal, because Visconti wanted the audience to recognize it as real but still artificial. It was quite complex — sometimes the city had to look real, and sometimes it had to look fake — but we got it, I think.”

American director Stanley Kramer agreed; after viewing White Nights, he hired Rotunno to shoot his star-studded end-of-the-world epic On the Beach (1959). The following year, Rotunno reteamed with Visconti on the classic Rocco and His Brothers. In recognition of the cameraman’s artistry on the film, Italy’s journalists honored him with the Silver Ribbon, one of the country’s most prestigious awards (Rotunno eventually earned a remarkable total of eight, in addition to the many other garlands he received in his homeland).

Rotunno recalled shooting the climactic nighttime street fight between Rocco and his brother, Simone: “I had to cover a big section of the street, but my light was almost 100 meters away from the subject. Sometimes I needed to double the light to reach one of the actors [ who was deeper in the frame], and to have enough light for the exposure; of course, the light had to seem as if it was coming from the same point. That involved many difficulties, but we did it.”

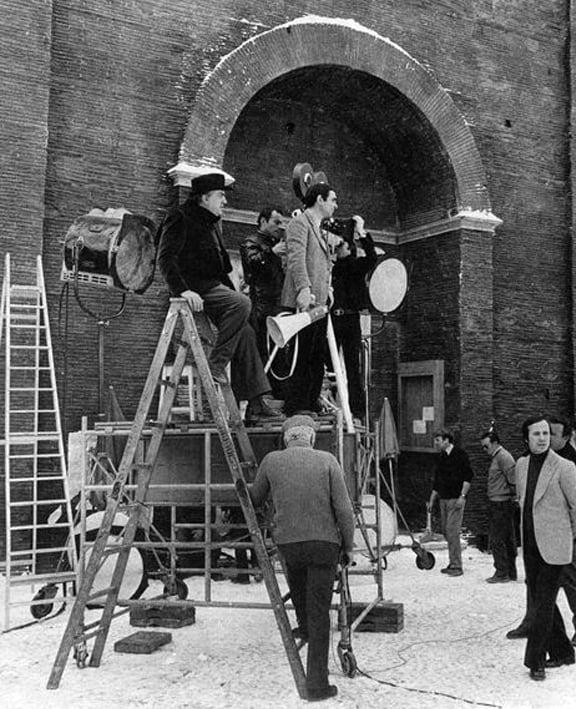

Visconti started a unique cinematography tradition on Rocco and His Brothers, which he observed on every subsequent film he made with Rotunno: each scene was shot using three cameras, not for coverage but for continuity. “Each camera captured its own piece of the story,” Rotunno explained. “When the actors filmed a short segment and we changed the shot, relit, and started again, we sometimes lost the vibration of the performance. By shooting with more cameras, Visconti could film a big piece of the story all in the same moment. The scene would start before one camera, and then we’d move in another camera; the scene would continue to play until the actors left the second camera and we picked them up with the third camera. For the director it was much better, but it was terribly difficult for me, because there was no room for the lights. Practically everything was in the shot except the corner where we placed the cameras.”

Visconti’s desire to use three cameras in the cramped laundry location where Rocco worked was particularly challenging, but Rotunno had the opposite problem while shooting the lush palazzo of landowner Prince Salina (Burt Lancaster) in The Leopard (1963). The climactic hour-long banquet scene, in which the Prince faces his decreasing power and influence in 19th-century Sicily, is considered one of cinema history’s great setpieces, and was shot under strenuous circumstances.

The sequence was filmed with three cameras in widescreen Super Technirama, within a real palazzo illuminated by thousands of candles. “To create the atmosphere, we studied all the painters of the 19th century and earlier,” Rotunno noted. ‘‘Although it wasn’t very realistic, Visconti felt that the quality, density and direction of the candlelight represented the richness of the place. Of course, because we were shooting in Technirama in 1962, the lens was not so fast, and we needed a great deal of light. The candles were basically props; my light was over the chandelier. I made a wooden crown on the chain between the chandelier and the ceiling, and I reproduced the candlelight exactly. I put some light in the foreground for close-ups, but with three cameras, it was almost impossible to light [ anywhere but from above] — we had mirrors everywhere, and there was practically no corner of the set that was out of the shot. All of our lights were on dimmers, and we used as little light as possible, because it was really, really warm; it was summertime, and we had all of these people enclosed in various rooms with candles. As we moved from one camera to the next, I got many drops of wax on my neck, and so did Visconti. I had trained the whole crew for days to put out the candles when the scene stopped. There were a thousand candles, so everybody had his section, including me. I felt like a priest in a church!”

Rotunno’s final feature with Visconti was The Stranger (1967), which immediately preceded the start of his most famous collaboration, with Federico Fellini. As with his previous associations with De Sica and Visconti, Rotunno knew Fellini for a long time before they ever worked together. In fact, Rotunno recalls first meeting with Fellini in 1959 to discuss shooting 8½ — a job he didn’t take because he was preparing to follow up his work on Mario Monicelli’s The Great War with another project, The Organizer. By the time Rotunno realized that the project was postponed, Fellini was already shooting 8½. (Rotunno eventually filmed The Organizer in 1963.)

Fellini later approached the cameraman to work on a film about a musician, The Mastorna Journey, but then became ill. “I stayed with Fellini for a year, doing all the things you do for a friend who is very sick,” said Rotunno. “The film was postponed, but Fellini told me I couldn’t leave him.”

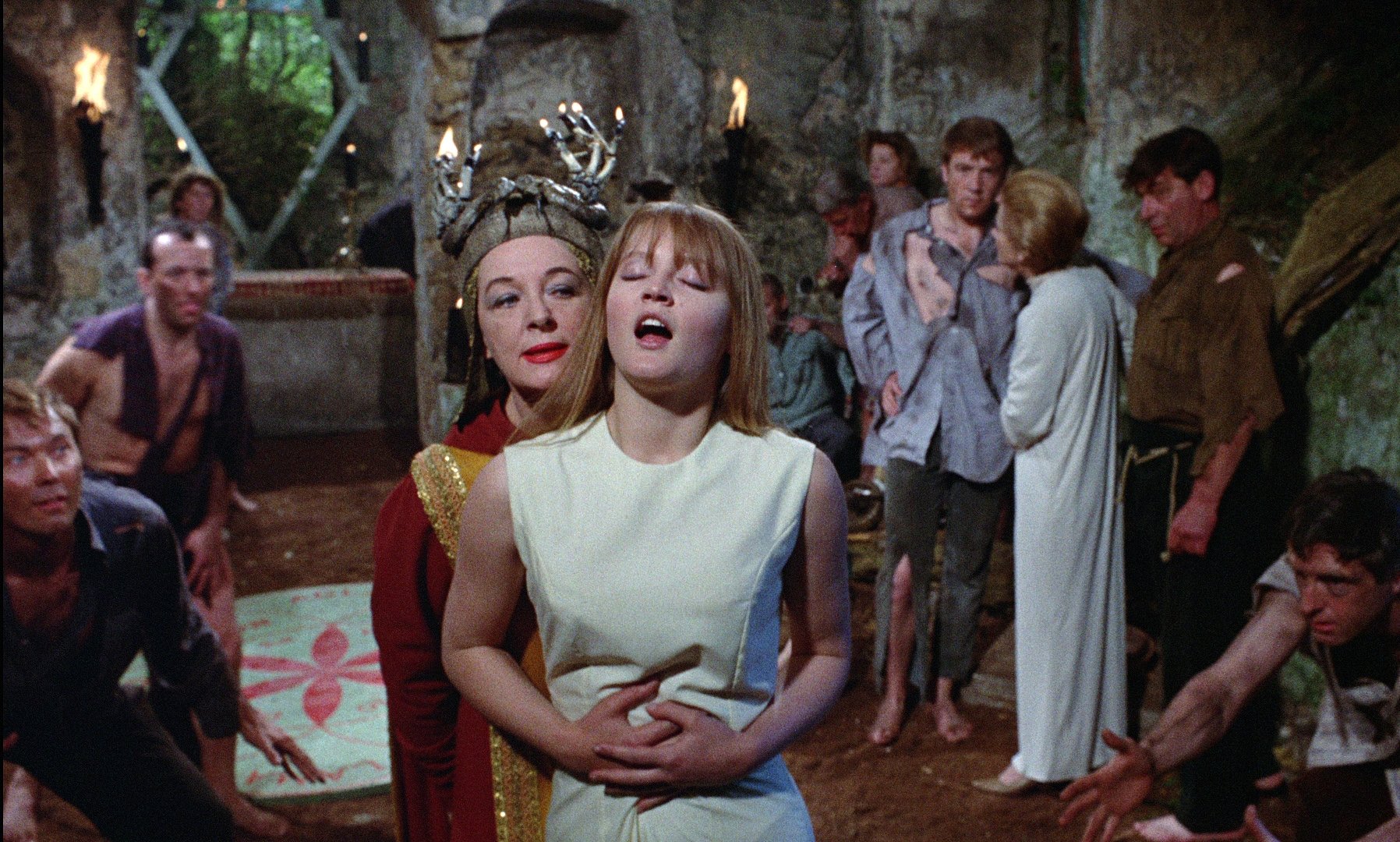

The filmmakers finally began their collaboration on the highly regarded Toby Dammit segment of Spirits of the Dead (1968), an omnibus film based on tales by Edgar Allan Poe. Rotunno’s brilliant reddish lighting lent an eerie, dream-like quality to the film’s opening sequence, in which the titular character, a dissolute thespian played by Terence Stamp arrives in Rome at sunset; the lighting effect simulated the character’s druggy point of view, with the “sunset” lingering long after the sun had actually set.

The filmmaking duo next teamed on the opulent Satyricon, based on the book by Gaius Petronius Arbiter, which only survives in fragments. Satyricon effectively captured this fragmentation, and went on to earn a Golden Globe for Best Foreign Film and an Oscar nomination for Fellini’s direction.

The largely stagebound film was shot over eight months, and Rotunno delighted in capturing Fellini’s bizarre tableaus while exercising extreme control over his cinematography. “It was like an astronaut’s dream,” he mused. “Inside a rocketship, you feel still things, but everything is moving fast around you. Satyricon was really a subterranean dream — everything was shot like a memory and it wasn’t intended to be realistic.”

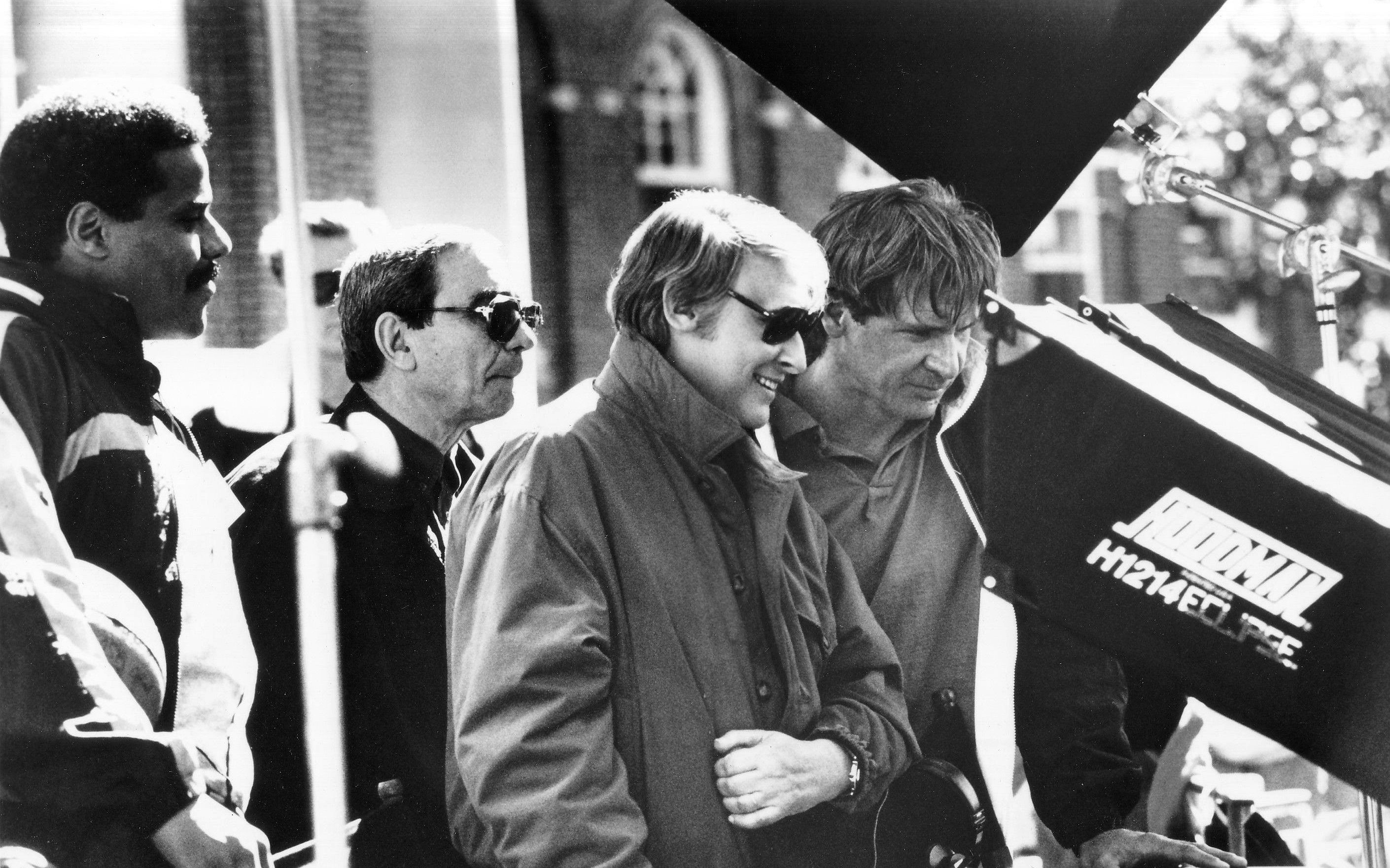

The same can be said of Rotunno’s brief stint on Fellini’s next project, The Clowns, for which he filmed only the flashback memory sequences before joining Mike Nichols on Carnal Knowledge. He would continue his collaboration with Nichols many years later on both Regarding Henry (1991) and Wolf (1994).

Rotunno and Fellini reteamed on Roma, an impressionistic portrait of the Eternal City which netted a Golden Globe nomination for Best Foreign Film. Roma broke with usual baroque look of Fellini’s films; in terms of visual style, it was more like a throwback to Rotunno’s documentary reportage. “It’s a memory film, but it is really realistic in the memory,” the cinematographer said. “I was born in Rome, and I knew the city well, so it was much easier to reproduce it in a realistic way. When we shot the traffic jam [on the autostrade], we put a big Chapman Crane on a camera car and drove around. The whole crew tried for several days to catch the ambience, but we never got it. The reality in this case worked against the memory, so we had to re-create it in the studio. Later, when we filmed the sequence in which the motorcycle drives around Rome like crazy, we were so noisy that somebody shot at us with a gun!”

Before his next project with Fellini, Rotunno began a three-film association with Lina Wertmuller comprising Love and Anarchy ( 1972 ), All Screwed Up (1973) and A Night Full of Rain (1978). He also shot his first musical, Man of La Mancha(1972), for Arthur Hiller. “Everybody sung except the director and me!” Rotunno recalled with a chuckle.

Rotunno then reteamed with Fellini on Amarcord (1974), an affectionate memory piece about life in the director’s hometown of Rimini during the 1930s. Featuring an array of lovably eccentric characters, the picture won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film and remains one of the director’s most popular works. “I knew all of the characters personally, because I had met them with Federico many, many times before we started shooting,” Rotunno noted. “In a way, I tried to put my memory in a condition very close to Federico’s. What is in the film is just a small representation of the real characters. I guarantee that if we had portrayed them in a realistic way, it would have been most unbelievable!”

Amarcord begins with the townspeople of Rimini building a huge bonfire (or fogarazza) on a pier to celebrate the end of winter. Rotunno used warm red gels to lend the lighting a nostalgic feel as Fellini introduced his characters. “The cameras went close in and followed the actors, and never came out further until the end of the film, when the young boy is again alone on the pier,” Rotunno said. “The idea was to put the audience inside of the story from the beginning to the end of the picture.”

Casanova, the pair’s next project together, is arguably the most personal, ambitious, stylized and mesmerizing of Fellini’s later films, and yet it was the least wellreviewed. “It was the most difficult film that I made with Fellini, really heavy to do, and frankly it is my favorite,” Rotunno said. “Fellini did 8½, which was about a crisis of imagination and creativity, when he was very young, but Casanova was about the old age he was really feeling. Fellini and I journeyed around Europe like Casanova; we went to Germany, Venice and England, and I think we were able to do a good job recreating the interior of a powerful prince’s German home, the warmth of an Italian salon with paintings on the wall, and the foggy atmosphere of the English countryside. I would say it’s maybe Fellini’s best and most beautiful film.”

In one of the film’s most unforgettable sequences, Casanova (Donald Sutherland) meets his mother ‘at a theater, where massive candelabras are lowered around them and snuffed out. Rotunno described, “Casanova first meets his mother in a box in the balcony of the theater, and she is represented like the imagination, like a vision for Casanova: she is shadowy, and then her face appears. I did everything in this moment, with this scene, these characters, and the light, to create an illusion that would emphasize the meaning. The chandeliers were hanging up on the stage, and then they were coming down until the men could reach them with the snuffers; when the lights were going out, they were on dimmers, because the effect had to be realistic. Again, I have no secret; I did it with my talent and my intuition. We tried to give the impression of the truth, but nothing more.”

One of the tougher Fellini assignments was Orchestra Rehearsal (1979), which presented an orchestra as an allegorical microcosm of a troubled world. The film was made for Italian television and shot on one set over a modest four weeks, after the director’s ambitious contemporary fable City of Women was postponed. Fortunately, the project got back on track the following year, and proved to be one of Fellini’s most successful films. “Fellini always worked with his own dreams, but City of Women is his most dreamlike picture,” Rotunno said. The picture’s climactic sequence is also its most surreal, as Marcello Mastroianni takes a wild, sexually charged ride down a mad amusement park slide. The 200'-tall slide set was built on Cinecitta’s backlot, and Rotunno directed his electricians to cover it with lights: “We set up many thousands of bulbs, with big bulbs in the foreground and small ones in the background, to make the slide look longer and make the perspective point of view move faster. Everybody said that Fellini and I built the slide for ourselves, and not the actors — to play, you know? Sometimes we sat on the slide together and went down with Marcello; I had a small light in my hand which I crossed over his face to create more movement.”

Rotunno’s last collaboration with Fellini was the whimsical fantasy And the Ship Sails On. In one of the film’s most memorable scenes, a group of musical artistes touring the ship happen upon the boiler room, where they give an informal recitation. “That sequence was shot on a very tall stage, which made it easier to light because there was more room — it’s much easier to control the illumination when you can place lights farther away. When I can move, I can do everything! The lights were placed above and below the actors. Below, it had to be very dark, so I used a reddish color that came from the fire inside the boiler as the coals were stoked. Above, I used golden light on the faces of the singers, using a window behind the doorway as the motivation. The two types of lighting were intended to signify hell and paradise.”

After completing work for And the Ship Sailed On, Fellini called Rotunno to make three extravagant TV commercials for a large Italian bank, but fate determined that the two friends had worked together for the final time. “We always talked about doing another film,” Rotunno said. “When Federico was sick, he was in the hospital in Ferrara, a beautiful town in northern Italy. When I went to visit some relatives there, I called Federico, and we talked and talked. He was very weak, but he told me, ‘Peppino, listen, why don’t we meet next Saturday in front of Cinecitta?’ I think he didn’t want me to see him in the hospital. Unfortunately, he never arrived at the studio.”

Just before shooting And The Ship Sails On, Rotunno completed Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz. During the following decade, he also worked with such accomplished directors as Robert Altman (Popeye), Alan Pakula (Rollover), Richard Fleischer (Red Sonya), Terry Gilliam (The Adventures of Baron Munchausen), Sidney Pollack (Sabrina) and Italian shockhorror maestro Dario Argento (The Stendhal Syndrome). He also experimented with the HDTV and Showscan formats.

In surveying his lengthy career, Rotunno liked to say that he created a great deal out of very little; he pointed out that just as music has only seven basic notes, cinematography has only three lights: “You’ve got the key light, fill light, and back light, out of which comes an infinity of results. The light is like a kaleidoscope, but those three lights mixed together are more touchy than the kaleidoscope. It’s difficult to ask a painter, ‘How did you paint the picture?’ I go with my eyes and intuition. I like so much to light, and I cannot stop. When I was shooting with Fellini, I was always lighting the next shot, because I was afraid to lose the idea of the light. My love for this work made it really easy. I work very hard, but the days seem only five minutes long. It’s a business I’m very, very proud of, because I was able to create a wonderful harmony with my directors, and to release their fantasies.”