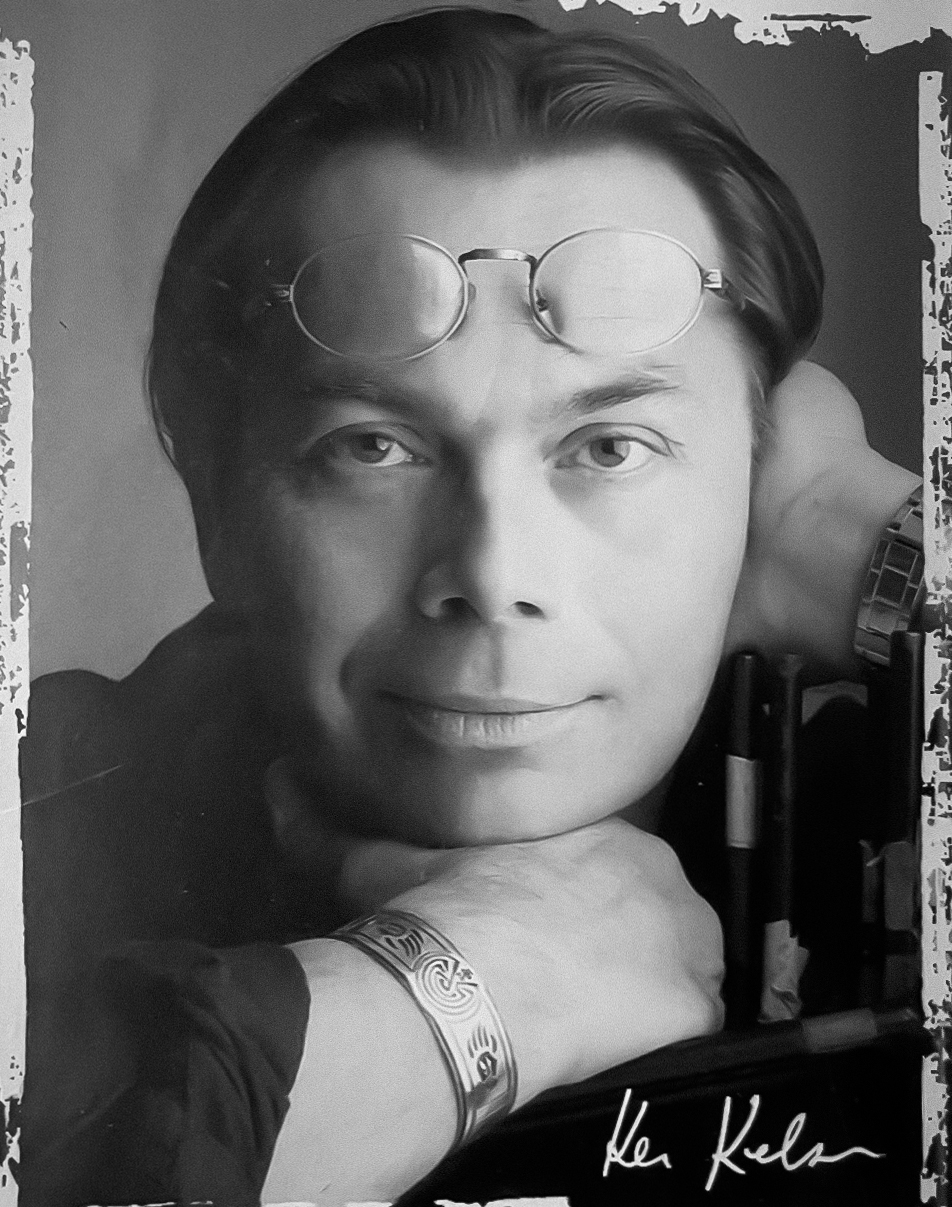

In Memoriam: Ken Kelsch, ASC (1947-2023)

Known for his vivid depictions of New York City in films including Big Night, Bad Lieutenant and The Addiction, the cinematographer died on Dec. 11 at the age of 76.

Personal photographs courtesy the Kelsch family.

“My kids used to ask me ‘Daddy, what’s your favorite color?’ and I would always say ‘dark,’” Ken Kelsch, ASC told one interviewer when discussing his career path. “In my soul, I’m a pretty dark guy, attitude-wise and everything else.”

Born in Brooklyn, NY, on July 8, 1947, Kelsch was one of four children, At the age of 12, he already had an interest in photography, and even had a darkroom — encouraged and instructed in the basics by his father. The process of taking pictures and interacting with his subjects helped him cope with his bashful nature, and he became the president of his seminary school’s photography club.

Kelsch’s father died when Ken was just 14, and his mother struggled to keep the family together and provide for them.

Growing up in northern New Jersey and seeking escape from an often difficult life, Kelsch was an avid moviegoer, and the sci-fi thriller The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms — featuring visual effects by Ray Harryhausen — left a strong impression on him. “I watched that three times at the movie theater one Saturday,” he told American Cinematographer. “I got a licking for not letting anyone know where I was that afternoon. I loved the horror genre as a kid. I was profoundly affected by Psycho, which I saw with my grandfather one great afternoon in a real, old-fashioned, big-screen theater in magnificent black-and-white.”

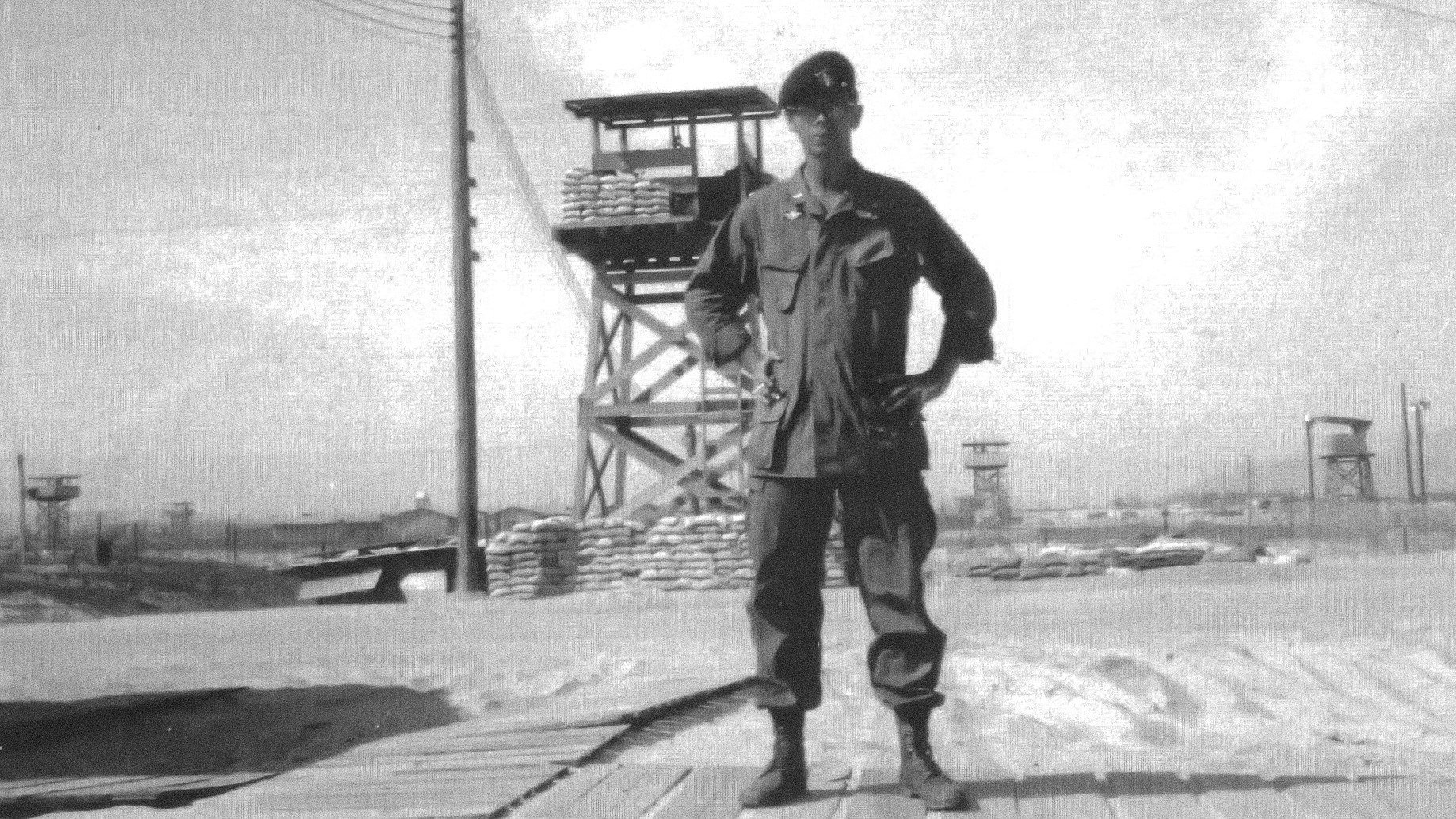

Upon graduation of high school, he had dreams of becoming a doctor, but early in his college education at Rutgers University, he dropped out to join U.S. Army. As his training progressed, he was quickly moved into more specialized instruction to become a member of the Special Forces — commonly known as the Green Berets — in 1965, and was soon shipped out to Vietnam at the age of just 22.

Serving as a first lieutenant within the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG) Command and Control North, Kelsch and his fellow soldiers were responsible for clandestine CIA-led cross-border operations in Cambodia and Laos and were involved with gathering intel on and interdicting enemy forces along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Based from Da Nang, these operations were harrowing. “I didn’t think I was going to be around to see my twenty-third birthday,” Kelsch recalled. And although he wanted to stay in the military, he had second thoughts and frequently pondered, “Would I make it through a second tour?” At the end of his first, in 1969, he was honorably discharged. (He discusses his service in this 2017 interview.)

After returning to the States, Kelsch sought to resume his interests in the visual arts, enrolling at Montclair State University in New Jersey to study photography, which led to filmmaking and shooting a short film that would gain him entry into New York University's Film & Television program.

“Beda Batka was my cinematography professor at NYU and a tremendous influence,” Kelsch told AC in a 2014 profile, naming ASC members Gordon Willis, Connie Hall and Michael Chapman as key influences and inspirations. It was also at NYU that he received his best the professional advice of his career, from guest lecturer John Cassavetes: “John told us to never stop shooting. Just figure out a way to do it.”

Working full-time while keeping up with his studies — and volunteering to shoot every student project he could to gain experience with different tools and techniques and learn his craft empirically — he finally earned his MFA in 1977.

In 1978, Kelsch got his first big break – shooting the cult-favorite horror feature The Driller Killer. It marked the beginning of his career as director of photography, as well as his long-standing working relationship with director Abel Ferrara, himself a native of the Bronx. Their initial meeting was unusual, as Kelsch related to British Cinematographer in 2021: “Abel called NYU graduate school and asked who was the best DP. They recommended me. I went over there [to meet], we smoked some cheap Mexican weed — that was my job interview. And then I started on The Driller Killer. It was myself, my future wife [Dale Denning] as my assistant — and the first woman first assistant in the union in IA — my two Dobermans to guard the equipment, my van, and some of the smaller lighting equipment I had.

“I got $100 per day for that. We shot in Max’s Kansas City [the legendary NY punk club]. In the last days of the shoot, I shot for 50 hours straight. I don’t remember much of it. We turned on the light in Max’s Kansas City, and every cockroach, every rodent came scurrying out of its hiding place. ‘Several pints of blood will spill when teenage girls confront his drill,’ was the tagline. And it opened in the Midwest in a bunch of drive-in theatres. We got our first review, and it said, ‘Abel Ferrara makes Tobe Hooper look like Fellini, and the lighting was so dark, it gave me a headache.’ We were thrilled. We actually got a review in Variety. Who cares what it said. It gave us some legitimacy.”

The duo went on to work together on 12 feature films, including Bad Lieutenant, Dangerous Game, The Addiction, The Funeral (for which he earned an Independent Spirit Award nomination), New Rose Hotel, ’R Xmas and Kelsch’s final screen credit, the melancholy 2019 documentary The Projectionist.

Of his work with Ferrara, a favorite of the cinematographer’s was The Addiction (1995), a contemporary vampire tale which finds a young woman (Lili Taylor) fiending for blood as might a junkie for heroin. “The problem with The Addiction was we had no money,” Kelsch told British Cinematographer. “I shot it black-and-white. I hard matted it in the camera in 1.85 to avoid 4:3 TV ratio in the transfer to tape. But they center extracted it. The last transfer I did for Blu Ray was much closer to my original vision. I thought it couldn’t be changed. I wanted to shoot Kodak Plus X [a black-and-white panchromatic] film but didn’t have the crew. I think we were three electricians and three grips. And we had no Condors or anything, so for a lot of the night stuff like that shot in a street in Manhattan, I had my guys to haul up my Maxi Brute on the building. This was brutal for those guys. It was a trying time. But to shoot black-and-white as a DP is great. You get nine shades of grey [Zone System]. You’re in a totally different environment. It is all abstract. As a DP, I consider myself a source-driven minimalist unless I am going to make a stylistic leap, where it’s going to be all stylized. I am capable of doing either way.

“Thematically again, it was all about resurrection, redemption. It’s the same thing over and over again because it’s obviously Abel’s concern. He is trying to figure out how to get out of the trappings of earthbound existence and somehow transcend the dirtbag that you are and go out to the next step on your spiritual plane.

“This is the most stylized of Abel’s films, not only in terms of my photography but also in terms of costuming, events, scripts, the acting. Christopher Walken was phenomenal. He took it and ran with it. Annabella Sciorra looked very stylized, like in old vampire movies, because this is all about resisting temptation.

“There is a lot of humor in the movie as well. Lili Tailor takes a lot of notes, develops her character; she knows her character’s backstory. There is nothing she can’t say about her character. It makes her the best actor around.”

Another breakout project for Kelsch was the much-loved 1996 romantic drama Big Night, a comedic look at the conflict between two Italian brothers struggling to keep their restaurant afloat. Co-directed by Stanley Tucci and Campbell Scott, who also star, the film is a foodie favorite, detailing the intricate work required to truly cook from the heart. This was a distinct departure for the cinematographer, who at that point had few other theatrical feature credits aside from his gritty work with Ferrara.

Addiction star Lili Taylor is the one who originally brought Tucci, Campbell and Kelsch together. "Lili was hassling them to hire me," the cinematographer told AC. "Of course, the six people dressed in black watching through their shades from the back row of the Angelica [theater in New York City] were the only other people who loved The Addiction," he joked.

When his Big Night interview finally happened, Kelsch "was very nervous and had nothing on my reel but scenes from Abel's films. At the meeting, all I did was tell amusing anecdotes about working with Madonna [who starred in Ferrara's 1993 picture Dangerous Game].

The fact that Kelsch's reel was filled with unsettling images didn't faze Tucci, who told AC, "It didn't matter that I didn't see anything similar to the look I was planning for Big Night. I'd seen Bad Lieutenant and I thought it was beautifully shot, more like a European film in its photographic style. Ken's work in Bad Lieutenant has a naturalistic feel, but it also has a sort of theatricality to it I hate the slickness of American movies — I prefer truthful, unaffected lighting. Ken never tries to make anything beautiful. And he did a wonderful job on Big Night."

Despite the problems inherent in making an ambitious film for $4 million in 35 days, Big Night was a big success.

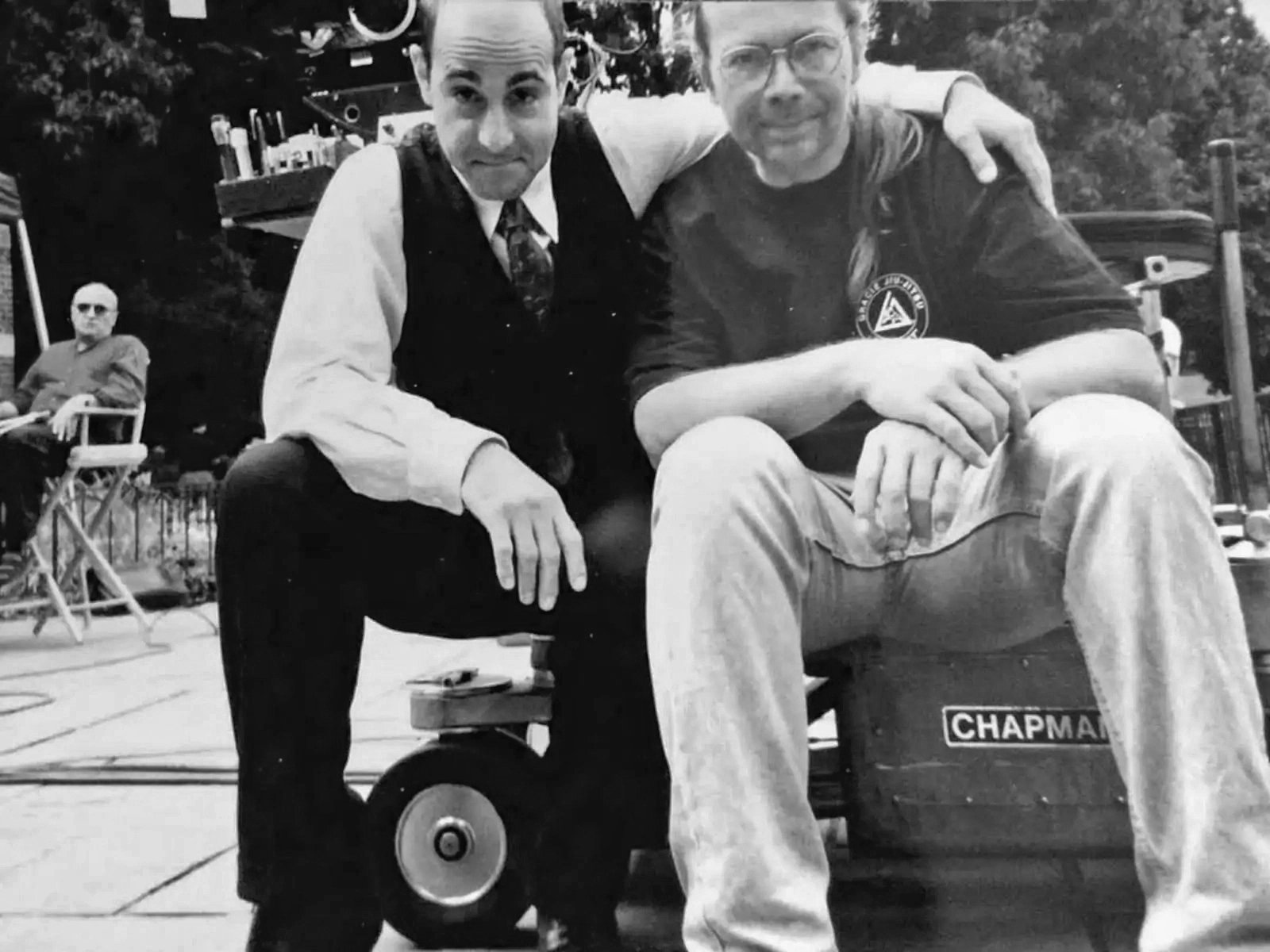

Kelsch and Tucci again collaborated on the screwball comedy The Impostors (AC Nov. ’98), which follows the adventures of Arthur (Tucci) and Maurice (Oliver Platt), two eccentric, unemployed, 1930s-era actors who are quite literally starving. Once they turn truly desperate, comedy ensues.

Tucci initially hoped The Imposters would photographically resemble a Marx Brothers film. "I would've loved to have shot in black-and-white," the filmmaker told AC. "We seriously considered it, but decided it would seem too self-conscious" and commercially limiting.

Once it was determined that The Impostors would be shot in color, Tucci's next direction to Kelsch was to "light it like a Marx Brothers movie." The cinematographer studied such classics as Duck Soup (1933) and A Night at the Opera (1935), but said he found their photographic style to be a "broadly lit, traditional. manufactured, studio look. I knew I wouldn't be able to do that without going home from the set with a migraine every day."

However, Kelsch, who quipped that he has "heard about fill light but I don't believe in it," took a cue from that old Hollywood comedic look, using "more fill than I ever have. I think the fill ratio in The Impostors is probably pretty close to Kodak's guidelines, which for me is a first. With more fill and soft light, The Impostors was a good experience for me, a total departure from everything else I've done."

Despite the rigors of shooting these two modestly budgeted shows for Tucci, Kelsch had nothing but praise for his collaborator: "I really respect Stanley and I appreciate what he is trying to do. That inspires me to go the extra mile. I don't walk away from productions too often saying 'This guy is my friend.' Abel Ferrara is less like a friend and more like a dysfunctional brother. The Impostors was the most pleasant film I've ever worked on.

"I would look around at that cast — Lili, Woody Allen, Alfred Molina, Campbell, Isabella — and sometimes my jaw would just drop thinking about what these major talents were doing, probably for scale. Stanley is such a friend and so supportive of these people that they'll all do just about anything for him. That's the definition of leadership."

Kelsch was invited to join the ASC in 1998 after being recommended by members Sol Negrin, Michael Negrin and Constantine Makris: “I’m incredibly proud to be associated with the world’s finest directors of photography,”

Among Kelsch’s many other credits are the features Spookies, Drop Squad, Susan’s Plan, Montana and It Had to Be You. For television, he shot the 1998 remake of Rear Window, starring Christopher Reeve, and the first two seasons of the series Medium, as well as occasional episodes of other shows.

Following Kelsch’s death, his son, Chris, stated via Facebook, “If you knew him, you probably have a story about him. He really was a great man, loved by many. A war hero who filled every room with his presence. An artist who never stopped being himself. A caring father who would do anything for his kids and grandkids. Shared his experience, wisdom, and love with all. Our family will deeply miss him and always love him as I’m sure many of you will as well.”

Kelsch is also survived by his daughters, Joy and Nina, and grandchildren, Gavin and Quinn.