In Memoriam: Michael Chapman, ASC (1935-2020)

The cinematographer and two-time Oscar nominee — best-known for features including Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and The Fugitive — passed on Sept. 20 at the age of 84.

The cinematographer and two-time Oscar nominee — best-known for features including Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and The Fugitive — passed on Sept. 20 at the age of 84.

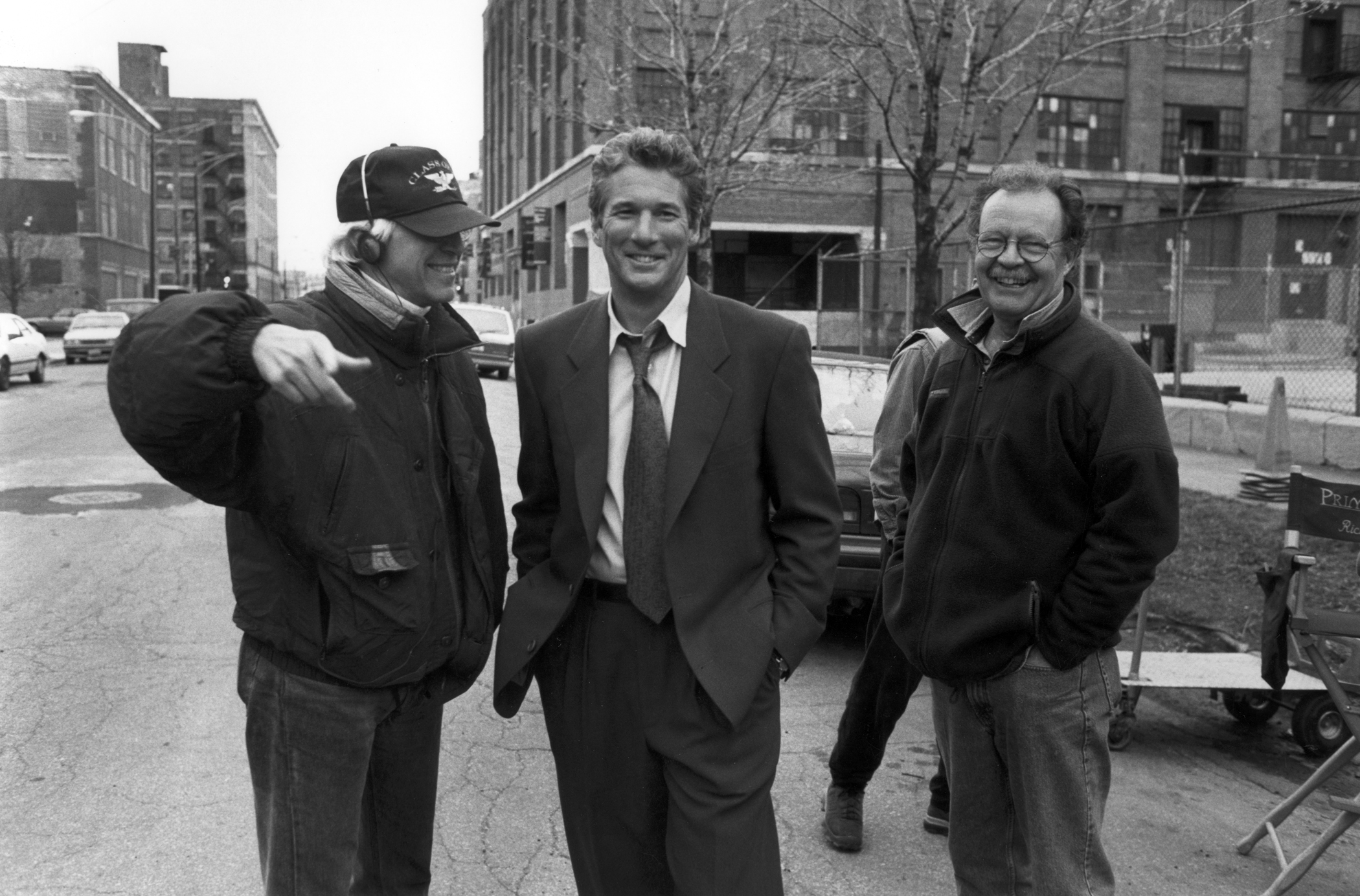

An influential figure in the New Hollywood that emerged in the 1970s, Michael Chapman, ASC shot more than 40 feature films. Twice nominated for Academy Awards — for Raging Bull (1980) and The Fugitive (1993) — he has also tried his hand at directing (The Clan of the Cave Bear and All the Right Moves) and screenwriting (The Viking Sagas, which he also directed).

Chapman’s varied contributions to filmmaking might suggest that he spent his youth striving to work in some form of visual expression, but he maintains that his entrance into the film industry was a “complete accident.”

Born in New York City on November 21, 1935, Chapman was raised in Wellesley, Massachusetts. As a youth, he was more interested in sports than photography or painting. “I was certainly as passionate about movies as any other kid in Wellesley,” he told AC contributor Jon Silberg upon being honored with the ASC’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2003. “But it never occurred to me that I could go get a job in that business — that movies were made by ordinary people who had families and who went to the bathroom. It was a whole other world to me.”

After he graduated from high school in the late 1950s, Chapman attended Columbia University, where his major was “useless knowledge” he says with a laugh. “There was a system at that time where you could basically take whatever you wanted and get your degree. I suppose I was an English major or a history major in some vague way.”

Upon graduating from the Ivy League school, Chapman went to work as a freightbrakeman on the Erie Lackawanna Railroad. “It was a very chic thing to do in the late Fifties — echoes of Kerouac and Ginsberg and all that,” he noted dryly.

The U.S. Army soon put an end to his railroad career. “This was back when they were drafting middle-class white boys,” said Chapman. “Fortunately, it was after Korea and before Vietnam, so I managed to get out of the Army without having to shoot at anybody.” After he was discharged, he returned to New York and married a Columbia classmate whose father, Joseph C. Brun, ASC, happened to be an Oscar-nominated cinematographer.

Brun, who had emigrated from France, was one of the most respected cameramen on the East Coast at that time. “He was a wonderful guy, but he was scandalized that his daughter should be married to a freight brakeman, so he got me into the [camera] guild. I started out loading magazines on commercials — there were very few features being shot in New York at that time — and I worked as an assistant camera, focus puller, clapper loader and all that.”

By the time Chapmen started working at the New York City-based commercial house MPO Videotronics, he was hoping to get a chance to move beyond the rank of assistant. MPO happened to employ some major cinematography talents, including future ASC members Gordon Willis and Owen Roizman. Chapman said it was his collaborations with Willis that made him see filmmaking as a passion, rather than just a job. “Gordy was offered a feature, and he asked somebody else to be his operator, but that guy had a chance to work on a series and foolishly turned Gordy down. When he asked me, I changed my card from assistant in a second. Then Gordy took me along for an amazing ride.”

Chapman operated for Willis on The Landlord (1970), Klute (1971), The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather Part II ( 1974). After overcoming some initial doubts about operating, Chapman realized that he was good at it, and that it gave him immense satisfaction. ‘‘I’d always been a good athlete, and there’s a lot of athleticism in operating a camera,” he observed. “That’s what makes operating so wonderful and seductive and exhilarating to do: it combines athleticism and aesthetics. I loved instantaneous framing and thinking as I went. It was like swinging a baseball bat. It’s wonderful fun, it’s sexy and it’s gratifying. You get to flirt with the actresses. What more could you ask for?”

After several successful years, Chapman decided he wanted to be a cinematographer. “I didn’t really lobby to shoot anything,” he recalled. “I didn’t know how to do such a thing — and I still don’t. I just hoped that an opportunity would come along, the way the chance to operate had.”

That’s just what happened: Hal Ashby, with whom Chapman had worked on The Landlord, began to prep The Last Detail (1973), and his top choices for director of photography were either unavailable or carried the wrong union card for the East Coast shoot. Ashby therefore decided to let Chapman come aboard as director of photography. “Hal is one of the Seventies directors that people don’t talk about enough,” said Chapman. “He was really good, and he made some wonderful films. I think The Last Detail is one of the best things Jack Nicholson has done. Besides that, I owe Hal a huge amount; he’s the guy who started my career as a cinematographer.”

As he had with his move up to operator, Chapman approached the transition to cinematographer with a mixture of confidence and doubt. “I was very lucky in that what I was asked to do [on The Last Detail] seemed to almost petition for a certain kind of look. It clearly was meant to look like the 11 o’clock news, and that’s what I said to everybody. But the reason I kept saying it was that the 11 o’clock news was the closest you could get to no lighting at all, and I was terrified about my ability to light! I figured there was no way I could light those scenes in a way that would have the power of the light that existed on location.” Chapman recalled a fight scene that occurs inside a train station men’s room: “We used a railroad station in Toronto, and existing lighting in the men’s room was the lighting in the film. I enhanced it a bit here and there so you could see the actors’ faces, but that was it.”

Whereas some cinematographers might want to show off a bit in their first outing, Chapman felt the opposite: “I wanted to be invisible — which, of course, turned out to be the right thing to want to be. I think The Last Detail is a wonderful movie, and I hope that part of its strength comes from its newsreel/documentary style, which was as much a result of my terror as anything else. Luckily, it happened to work out.”

After The Last Detail, Chapman began a very productive series of collaborations with director Philip Kaufman, who had commenced production on The White Dawn (1974). The drama concerned a group of whalers stranded in the Arctic, and “he was shooting with a Canadian cameraman who had made the bad tactical mistake of doing some tests,” Chapman said. “Phil was apparently so appalled by what he saw that he fired the guy, and then he needed somebody who had an East Coast union card.”

Chapman felt that this little-known film, which stars Timothy Bottoms and Louis Gossett Jr., was under-appreciated. “It’s kind of wonderful, and I really liked working with Phil. We also worked together on Invasion of the Body Snatchers [1978], which was a hell of a lot of fun, and The Wanderers [1979], which is a very rich movie, heartfelt stuff. I was very glad I was able to work so often with Phil.”

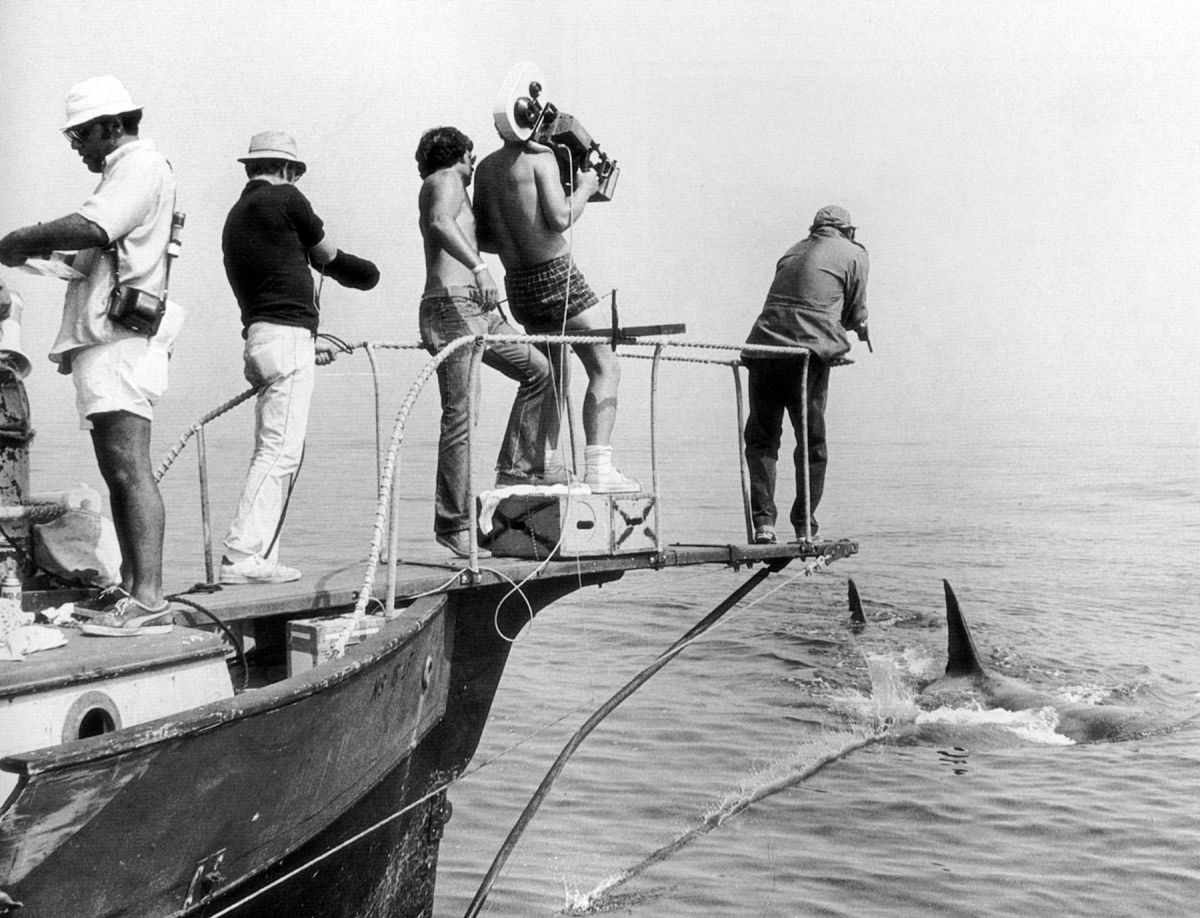

Following The White Dawn, however, East Coast cinematography jobs slowed down to a trickle, so when Bill Butler, ASC asked Chapman to operate for him on Jaws (1975), Chapman jumped at the chance. He says he never felt that operating again was a step backward in some grand career plan. “I was working overtime almost every day;’ he said. “My only thought was, ‘I’m going to make a very good buck all summer, so I’m a happy Chappy!”’

Of his extensive handheld camerawork on the blockbuster, Chapman said, “Bill and I figured out early on that I could handhold the camera on those small boats and roll with the waves as I climbed all over the place. I think it was very effective in terms of creating suspense, but there was really no other way to do it. I’d probably still do that film handheld today.”

Shortly after completing Jaws, Chapman landed a cinematography job that began one of the most important collaborations of his career, with director Martin Scorsese. The young filmmaker had directed a few low-budget features, including Mean Streets, and was planning a small drama about a New York taxi driver. Chapman read the script by Paul Schrader and saw tremendous artistic possibilities. “Paul could write like an angel,” he said. “Taxi Driver is as good a script as I have ever read — and it was very visual. So many of the little details in that movie actually were in the script.”

Taxi Driver most certainly did not call for the “11 o’clock news look,” and Chapman, now more confident in his skills, was eager to try new things. “The project had enormous visual possibilities, and we felt it would be correct to be unusual and to do odd things with the camerawork and lighting. It would have been a terrible mistake to do any sort of surrealism in The Last Detail, but with Taxi Driver, the whole script was laden with visual information and suggestions, and we went for it.”

The filmmakers used slow motion to great effect to show characters floating through the urban milieu, or to dissect moments of extreme violence. “Nowadays, slow motion is often done in a cheesy way,” said Chapman. “If you see somebody running toward you in slow motion, you know there’s going to be an explosion behind him. I think we used it much more effectively, but those ideas were Marty’s, not mine. Shooting straight down on a table and having a hand go across in slow motion — that’s me doing what I was told. If ever there was a director with a visual sense, it’s Marty.”

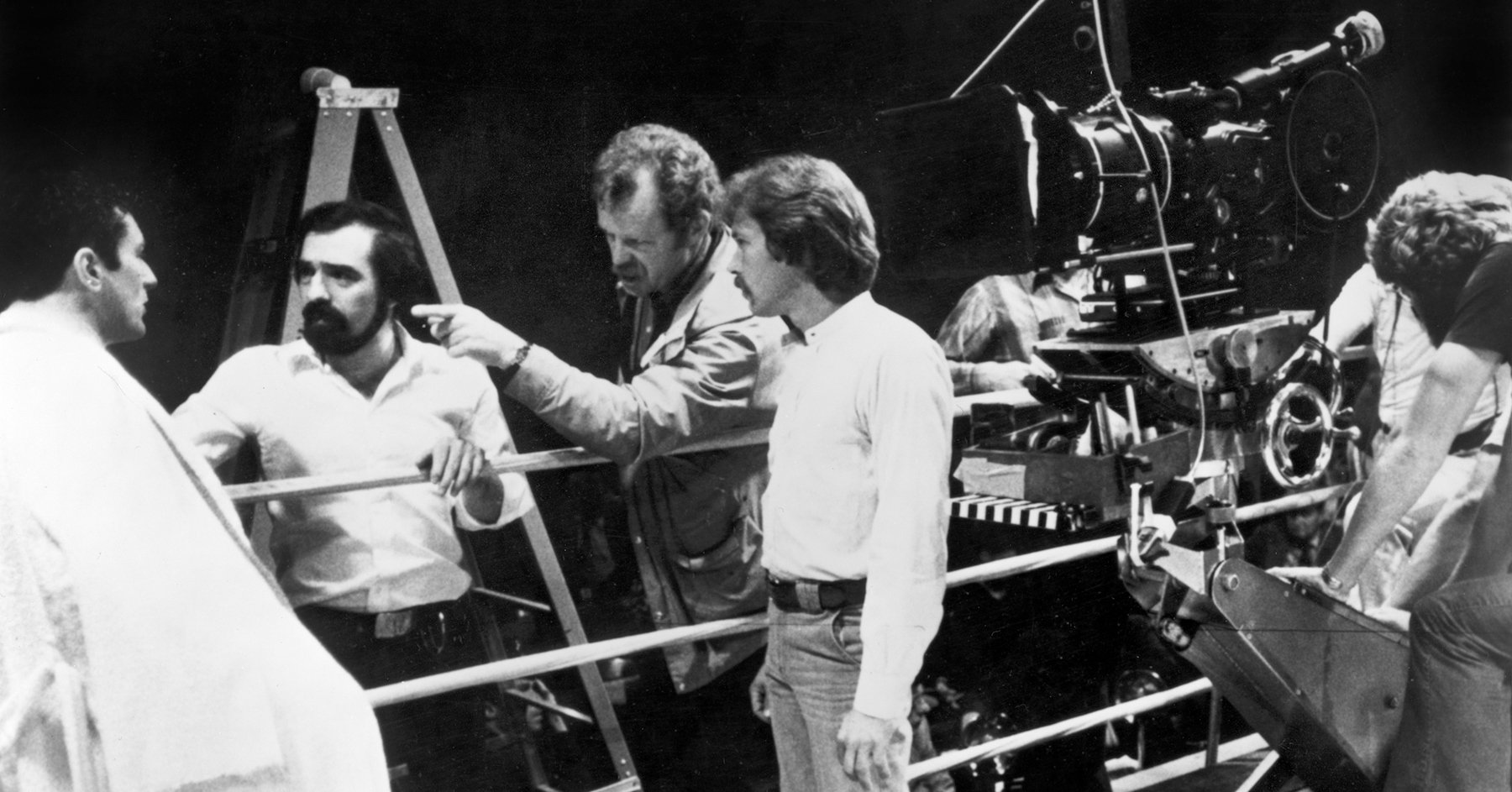

The duo next teamed for the ambitious concert film The Last Waltz (1978). Scorsese and Chapman, both fans of Robbie Robertson’s group The Band, wanted to create a documentary that would match the power of the music. “They wanted to go out with a big bang;’ he said of the musicians. “I did all the lighting, and it was showbiz lighting all the way. We had sets from the San Francisco Opera Company, and there were eight or nine cameras, which people like Vilmos Zsigmond [ASC, HSC] and Laszlo Kovacs [ASC] were operating. Marty and I knew all the songs, and we could draw storyboards for every verse — at this point zoom in, at that point dolly left. The strategy for filming all of their songs was planned out in enormous detail. Backstage, we had a whole roomful of people desperately loading and unloading magazines all night.”

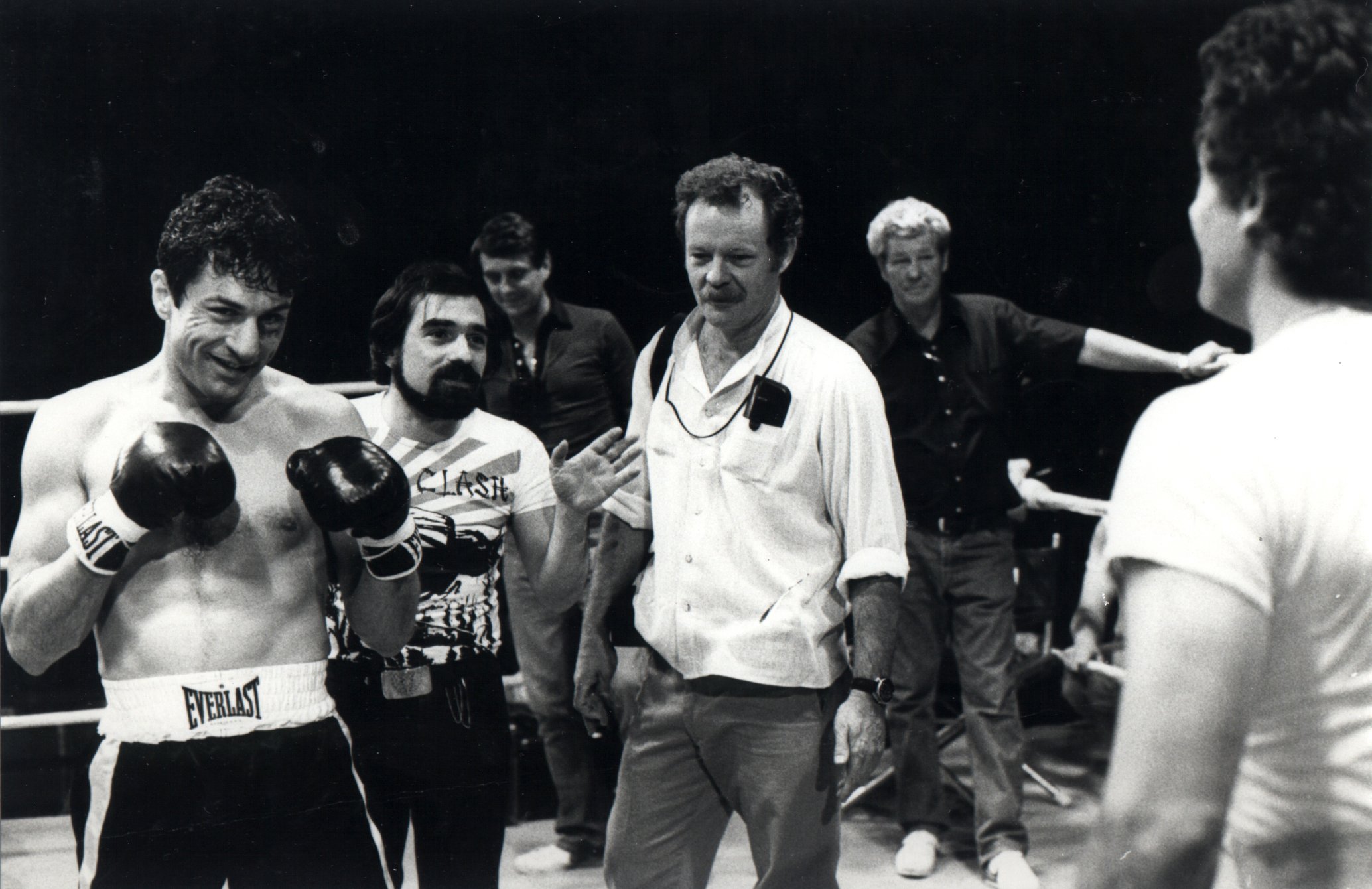

Shortly afterward, Chapman and Scorsese embarked on what would become a key film not only in their own careers, but also in the history of American film: Raging Bull (1980). Chapman’s black-and-white cinematography on the Jake LaMotta biopic was inspired by the media that had brought boxing into the filmmakers’ living rooms. “Boxing was black-and-white to us, whether it was the Friday night fights on TV or the graphics in Life magazine,” said Chapman. “And then there were all the movies we associated with boxing, like City for Conquest.

By that time, however, black-and-white motion pictures were rare, and on top of that, Chapman’s experience with the format was limited. He recalled, “I knew in theory that you had to use backlight to separate [ elements in the frame], and that you only had tones to work with. But I found that it was actually liberating to shoot black-and-white because it’s inherently more abstract than color. It’s one step removed from the reality of the red tie and the blue shirt. You start one step from reality, and from there, you can do pretty much whatever you want:’

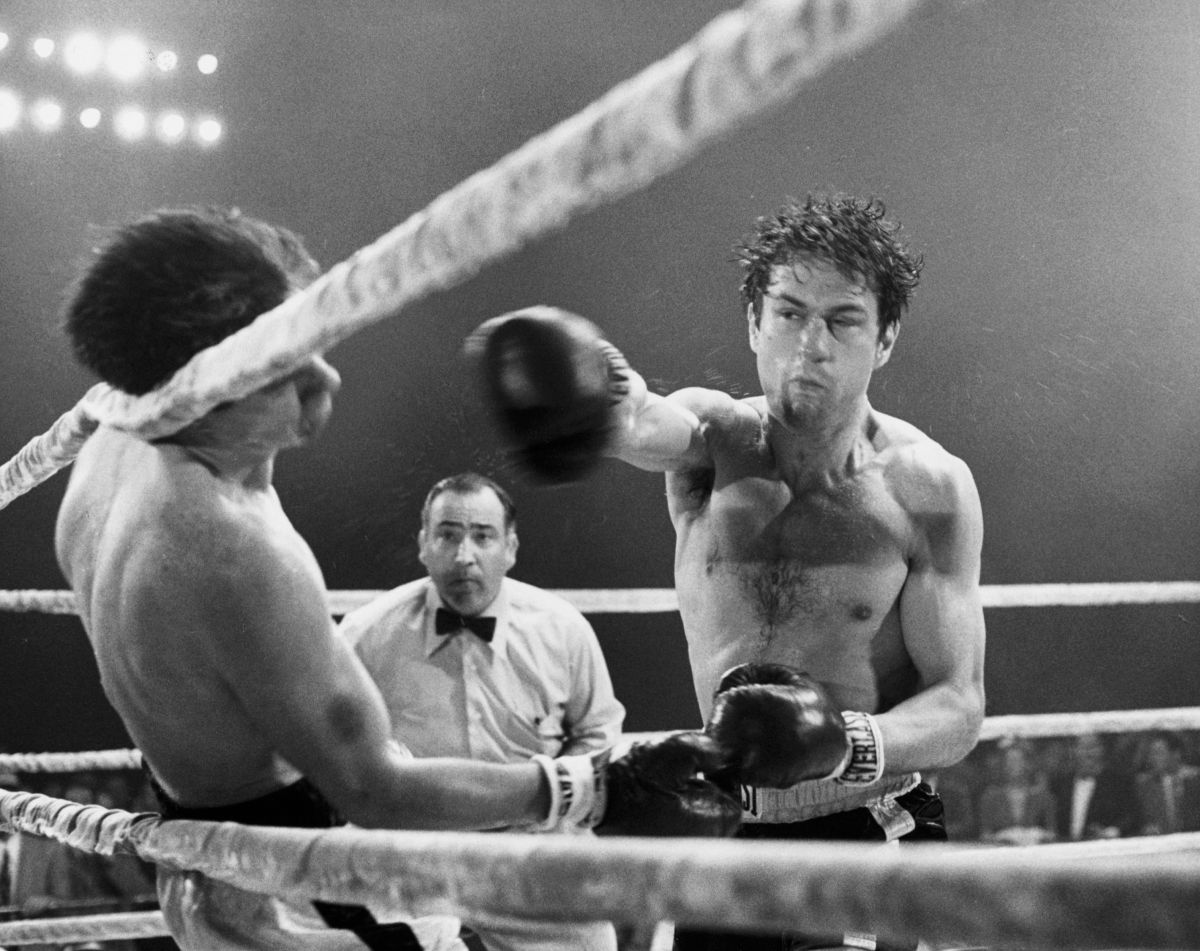

Chapman and Scorsese decided to cover scenes depicting LaMotta’s personal life naturalistically. “I lit those more like I would have lit them in color than I probably should say,” the cinematographer revealed. “Obviously, I had separation by backlight, but for the most part the lighting was pretty straightforward.” The scenes in the ring were another story. “Those were very much meant to be ballet. Like many of us, [LaMotta] was far more at home and at peace with himself when he was at work — or boxing, in his case — than when he was trying to deal with ordinary life, which he was obviously terrible at.”

Although Chapman had given up operating by that point, he decided he’d try to shoot the simulated home movies that appear in color midway through the film. He loaded a 16mm camera with reversal film and gave it a shot, but it was no use. “I was just too good;’ he recalled with frustration. “I couldn’t frame those scenes badly enough to make them look like real home movies. So I gave the camera to Marty, and he couldn’t do it badly enough, either. Finally, we got a Teamster to do it, and he got it just right!”

Among other honors, Chapmen earned an Academy Award nomination for his expert camerawork.

In 1999, Raging Bull was selected by American Cinematographer readers as one of the best-photographed feature films of all time, with AC editor-in-chief Stephen Pizzello noting:

The sport of boxing offers everything an ambitious filmmaker could want for the screen: physical and psychological conflict, drama, and suspense. Ironically enough, director Martin Scorsese, never a fan of the “sweet science” had to be pressured into helming Raging Bull by his onscreen alter ego, Robert De Niro, who brought him the source material: a confessional book by former prizefighter Jake La Motta. Still reeling from the failure of his lavish musical feature New York, New York, Scorsese found himself attracted to the true story's themes of self-immolation and redemption. As he noted in the book Scorsese on Scorsese, his own personal travails allowed him to relate more closely to the suffering endured by La Motta and those in his violent orbit: "I understood then what Jake was, but only after having gone through a similar experience... I was fascinated by the self-destructive side of Jake La Motta's character, his very basic emotions. What could be more basic than making a living by hitting another person on the head until one of you falls or stops?"

Once he agreed to film La Motta's story, Scorsese assembled some other old friends to help him bring the project to life: screenwriter Paul Schrader, editor Thelma Schoonmaker, and cinematographer Michael Chapman, all of whom had lent their skills to Taxi Driver.

The result of this collaboration is one of the most brutal and beautifully shot monochrome pictures of the modern age. In addition to rendering the noir trappings of New York's boxing heyday, Chapman used an artful combination of techniques — including Steadicam, handheld camera, special rigs, variable framerates, freeze-frames and a specially designed flashbulb simulator — to infuse the film’s fight scenes with a balletic energy that lent the combatants' vicious exchanges an operatic grandeur.

While prepping the project, Scorsese and Chapman drew inspiration from several classic black-and-white films, including Double Indemnity, Sweet Smell of Success and the Italian neo-realist classic Salvatore Guiliano. They were also influenced by the work of the great still photographer Weegee, who made his name working for the New York Daily News during the 1930s and ’40s. In addition, Chapman also screened several one- and two-reeler shorts by Buster Keaton: The Neighbor, The Fence, and The Blacksmith Shop. As the cinematographer told one interviewer, he remembered these short films as being "very clean, and somehow dealing with the fact of [photographic] separation without having to resort to backlight: just beautiful black-and-white with things in space separated entirely by gray scale.”

Using a wide array of lighting instruments, Chapman effectively illuminated the full arc of La Motta's spiritual fall and eventual salvation — a transformation that was physically embodied by De Niro, who famously packed on poundage to portray the fighter in his later, dissolute years. In one of the film’s key scenes, La Motta, in his new incarnation as a nightclub entertainer, performs a riff on Marlon Brando’s “I coulda’ been a contender” speech from On the Waterfront. As AC’s readers have confirmed, Raging Bull is indeed a heavyweight achievement.

In 2019, the picture was recognized by ASC members as one of the 100 most influential milestone films of the 20th Century — coming in at number 6.

When director Carl Reiner began looking for a cinematographer to shoot his film noir send-up Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982), he naturally thought of Chapman because of Raging Bull. The cinematographer fondly recalls his work on the Steve Martin comedy, which required him to use a variety of practical tricks to make his cinematography match the l 940s-era Hollywood scenes that would be blended into the film. “Steve and Carl were very nice guys, and we had a wonderful time making Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid,” he said. “We didn’t have digital technology, but it was still too good-looking in a way. Younger people didn’t know those [old Hollywood] actors, and they didn’t get the joke.

“That was the last movie I did with a gaffer named Don Scott,” Chapmen remembered. ‘‘I’d worked with him off and on for years. He was an old-timer, and he’d actually worked on some of the movies that we intercut [our footage] with. Much of what we did on Dead Men was archeology; we dug out old arc lights and had them cleaned up and polished. Don showed me techniques I didn’t know how to do, things that involved mirrors and pans of water, that they once used routinely. I don’t think anybody remembers how to do them anymore.”

Chapman went on to shoot a number of comedies, including Ghostbusters II (1989), which sparked a period of collaboration with director Ivan Reitman that included Kindergarten Cop (1990), Six Days Seven Nights (1998) and Evolution (2001).

“I had fun on all of them,” said Chapman. “I’m sure I adapted [my technique] to what was good for comedy, but, by and large, I don’t think you have to elaborately change your way of doing things. They always say tragedy is a close-up and comedy is a long shot, and I think that’s true. You want the joker and the jokee to be in the frame at the same time. On comedies, I use a little more fill light; you tend to create a lit atmosphere where the performers can be at home, where they can move around and do their jokes without having to hit a precise mark.”

Of course, by this time, Chapman was frequently creating images that would subsequently be manipulated or enhanced digitally. He recalls working on the comedic fantasy Space Jam (1996), in which basketball great Michael Jordan and other players freely mingle with animated cartoon characters: “That’s a great example of lighting an area and letting people perform in it. We had what amounted to a basketball court, and we set up several cameras — for close-ups, long shots and all that — and they followed basketball players playing against tall people in green suits. Once I lit it, there was nothing for me to do. I just hung out and watched.”

Although Chapman still loves his work, he had mixed feelings about the direction in which his craft is going. “In a curious way, I’m glad I got into the business when I did, because what I did as a cameraman was a more self-contained craft than what it seems to be today. I think the job I did, and still do, is disappearing somewhat. I don’t think it’s going to happen overnight, but 50 years from now it will be a very different world.” Nevertheless, he is excited about the overall future of visual storytelling, which he believed was still in its infancy. “If I were young, I would spend a lot of my time learning the digital end of postproduction. Why not? I’d love to get in there and paint; I’d love to make a movie that looks like Monet or Picasso. If you can get to the edge of abstraction, why not try it? It could be wonderful.”

In conclusion, Chapman insisted on debunking some of the myths surrounding the American New Wave of the 1970s. “I was involved in a ridiculous number of those movies, and I must say that it was much more about accidents or happening to be at the right place at the right time than any overarching genius on my part,” he emphasized. “Had I known at the time that it was going to be thought of as a great renaissance, I would have taken a lot more notes and paid more attention. We thought we were just making movies.”

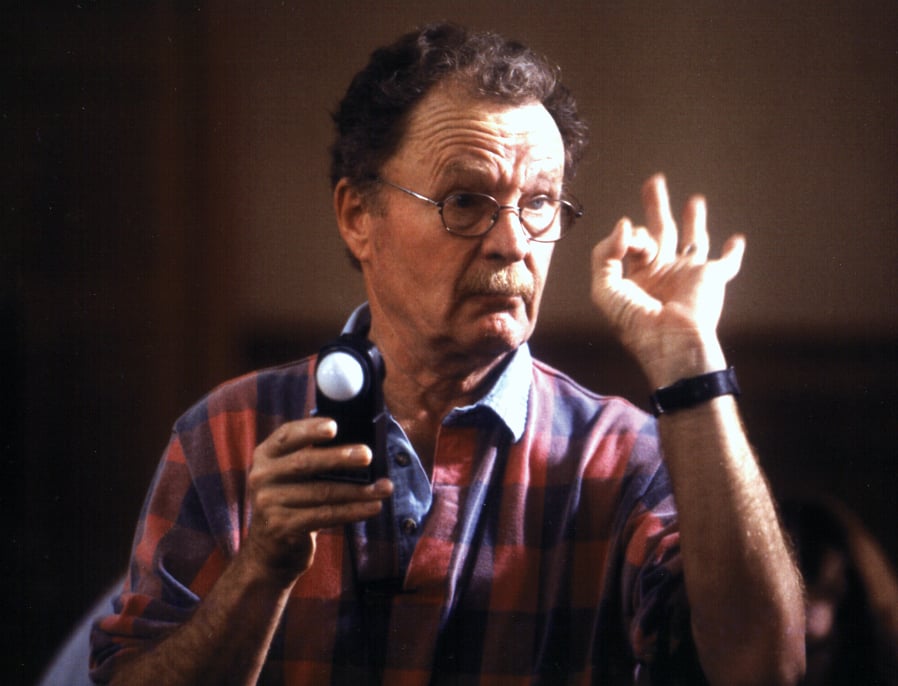

In 2016, Chapman was honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award during the 24th annual International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography Camerimage, held in Bydgoszcz, Poland. Though in frail health, he attended the event in person:

Chapman is survived by his wife of 40 years, screenwriter Amy Holden Jones, four children and four grandchildren.

Donations may be made in his memory to the Sherriff’s Meadow Foundation, which is dedicated to conserve the natural, beautiful, rural landscape and character of Martha’s Vineyard for present and future generations.

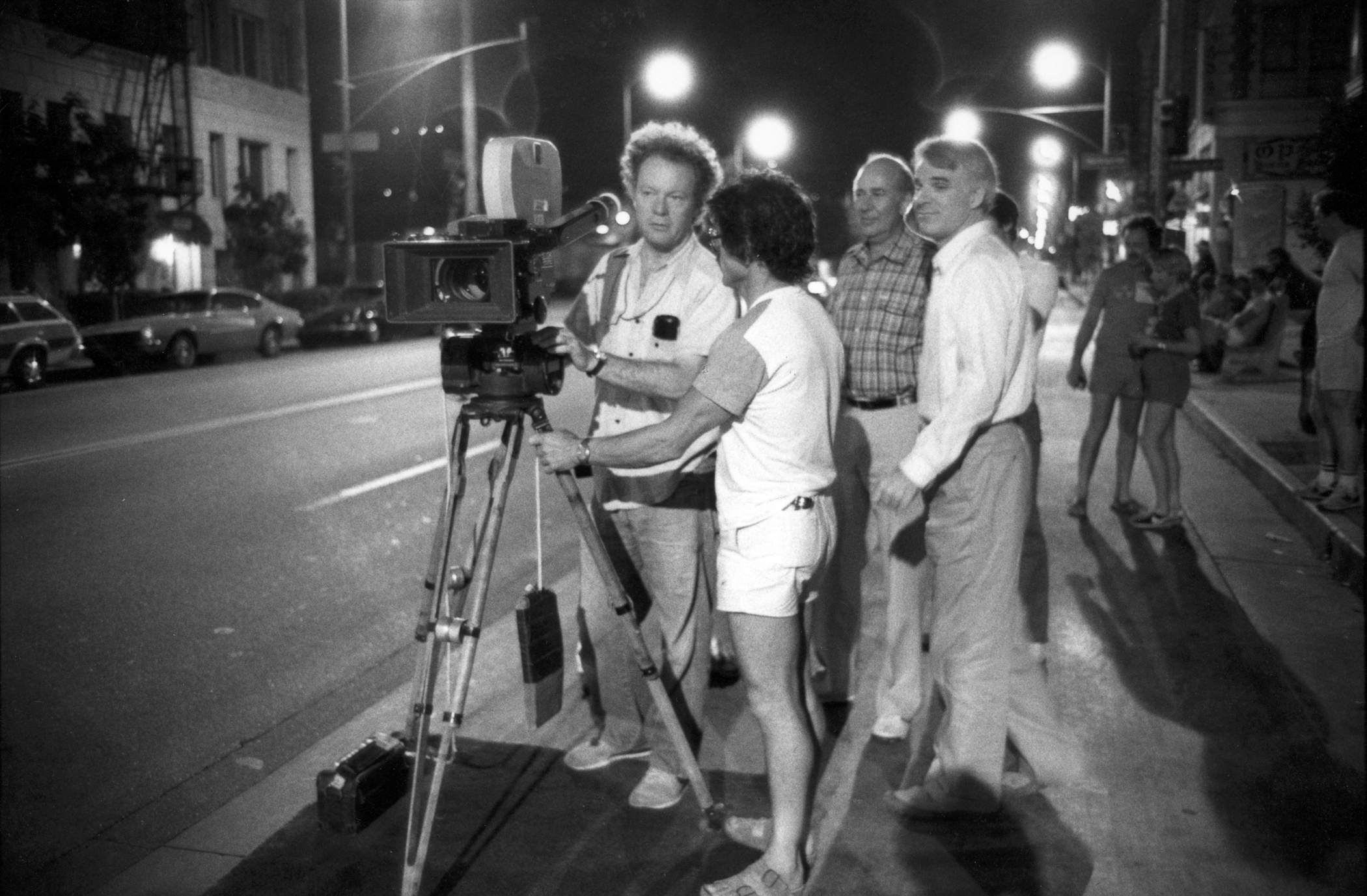

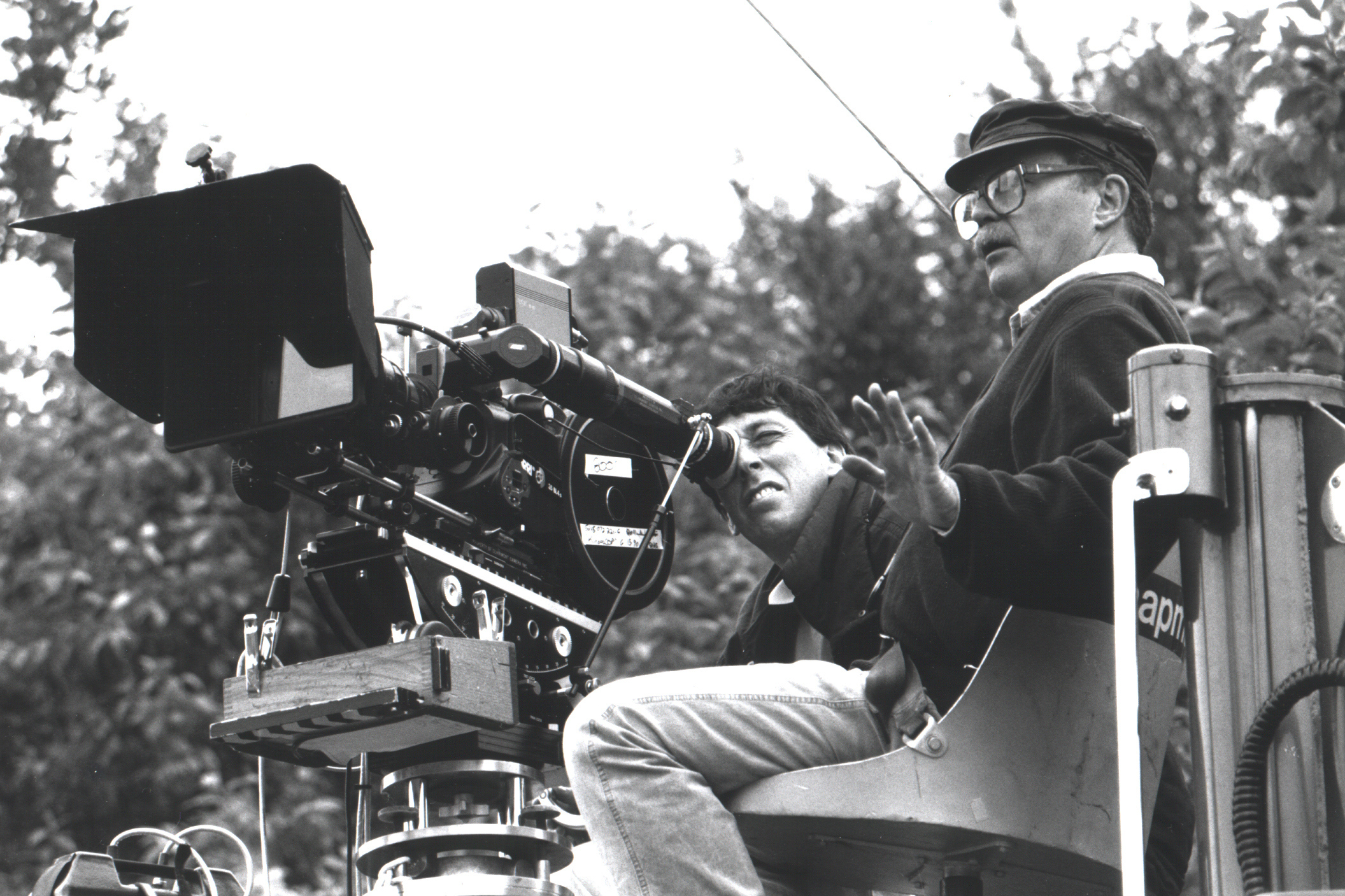

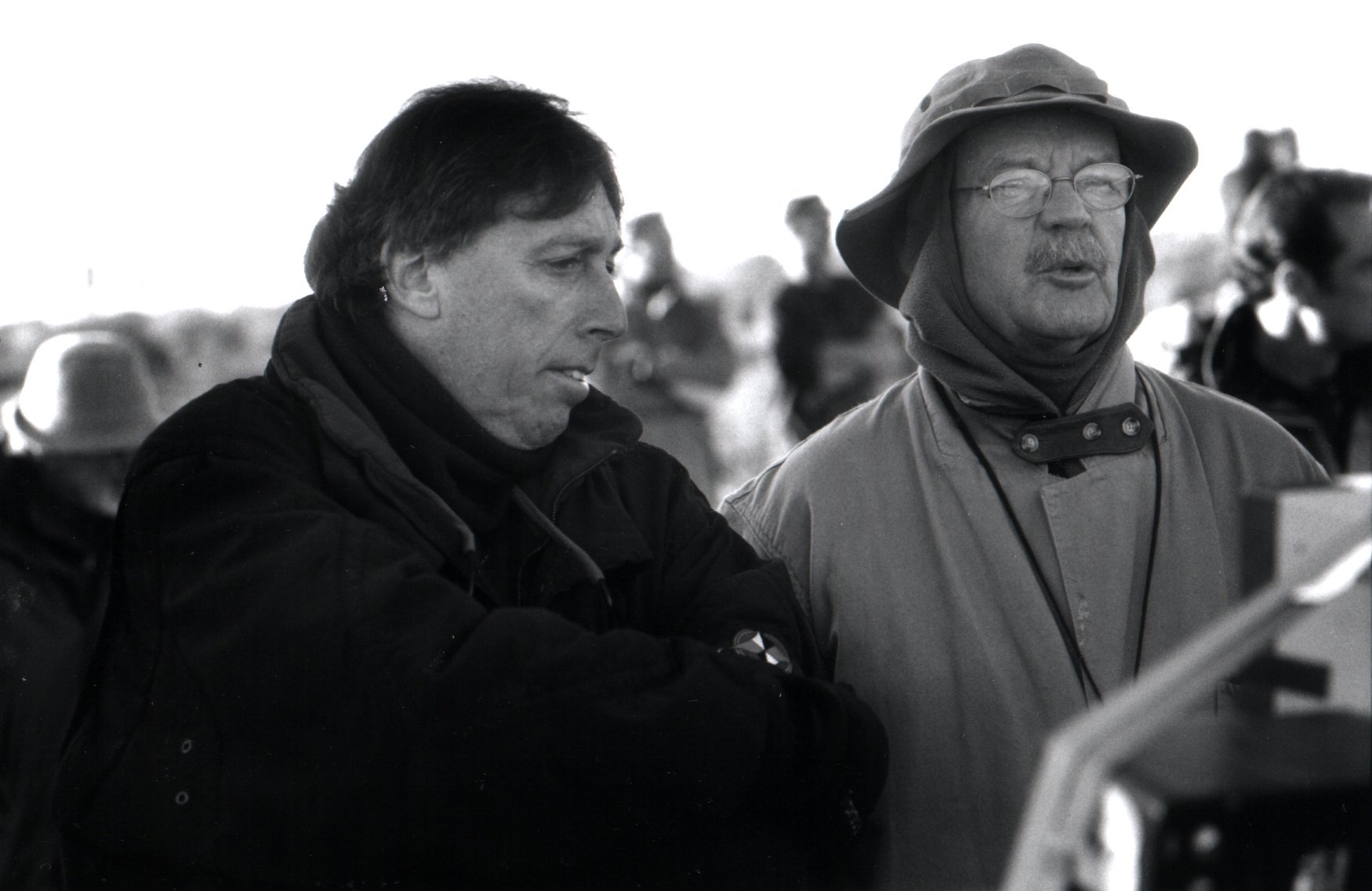

Here are some additional photos of Chapman and key collaborators at work, from the American Cinematographer archives:

This video tribute to Chapman demonstrates some of the cinematographer’s creative range across many projects: