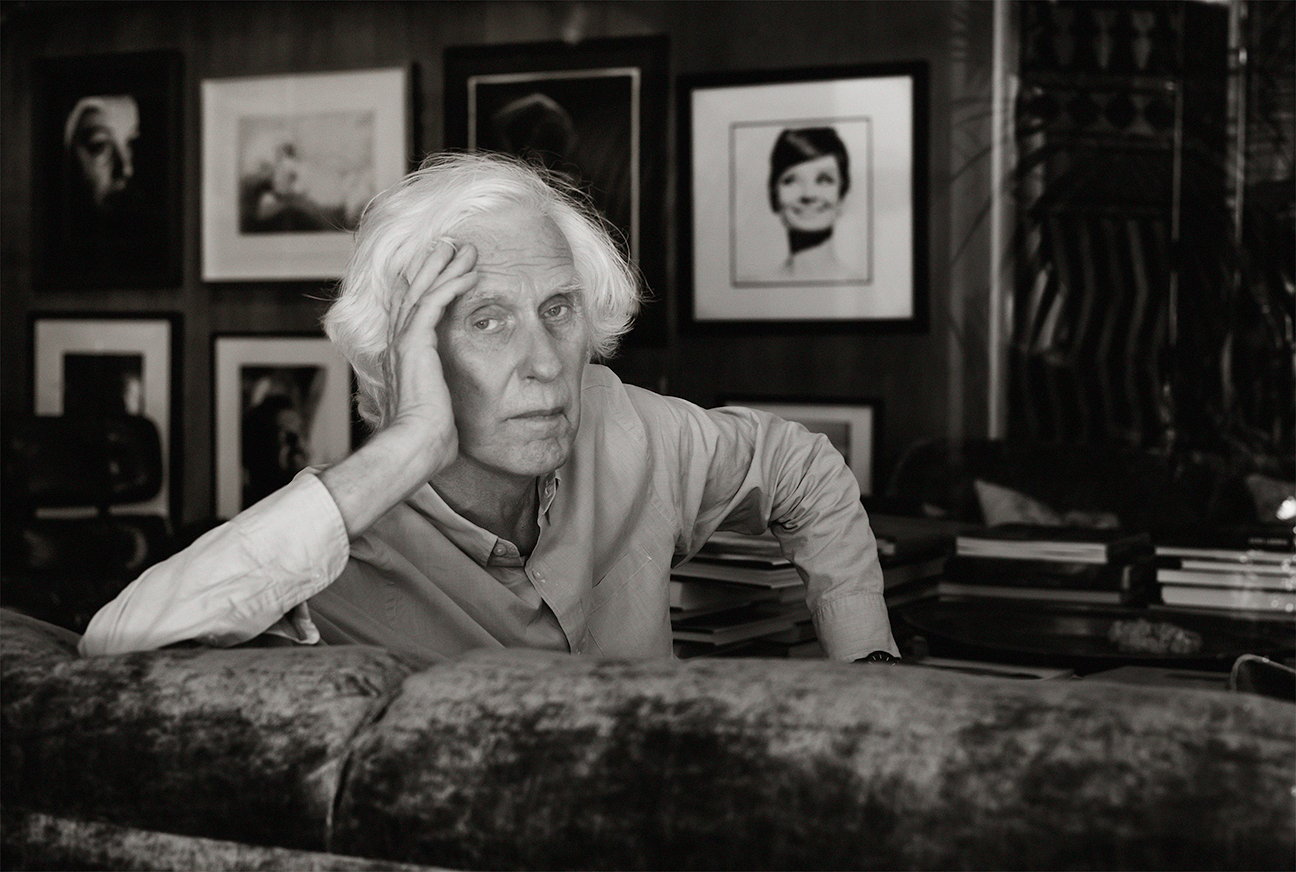

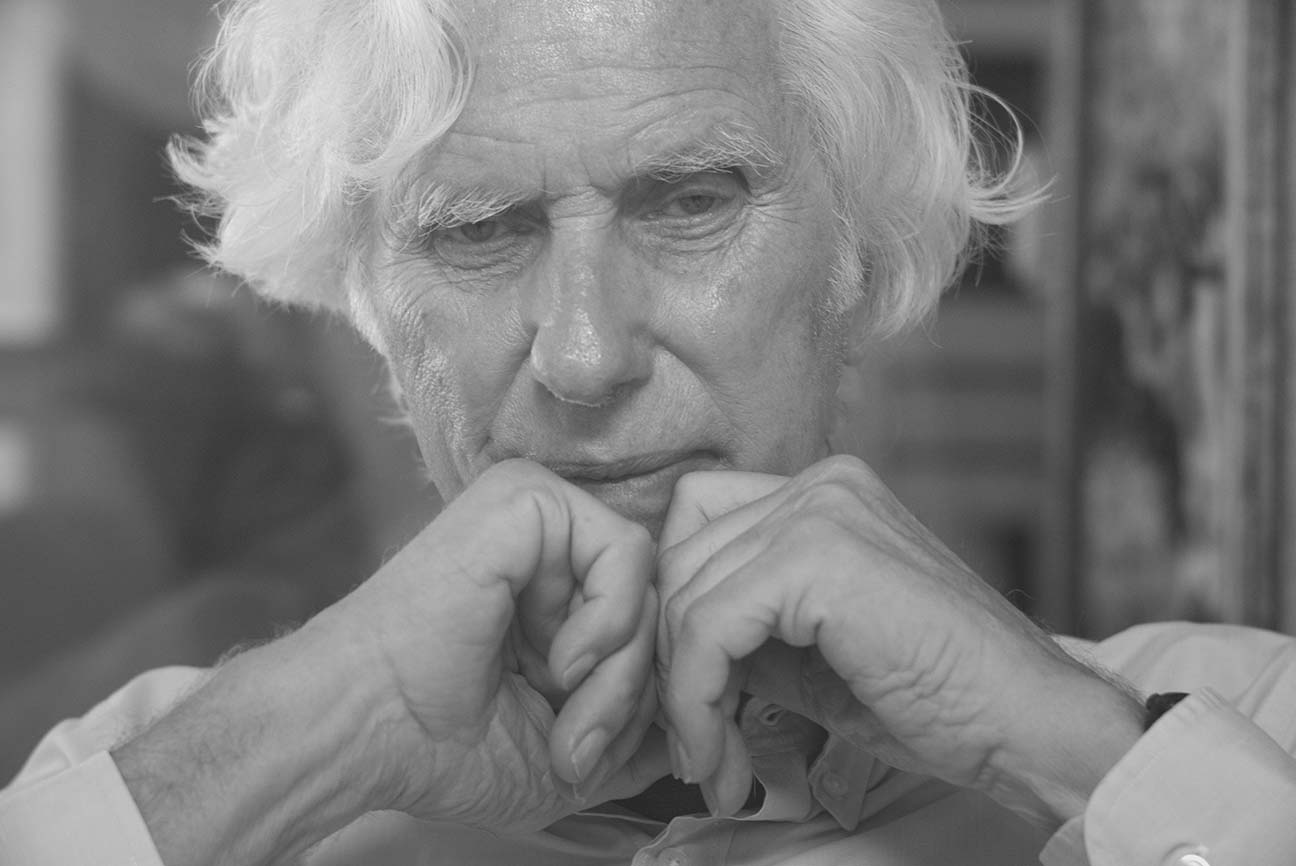

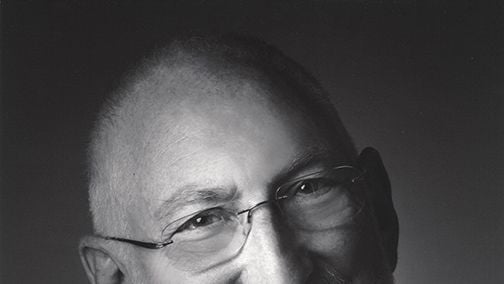

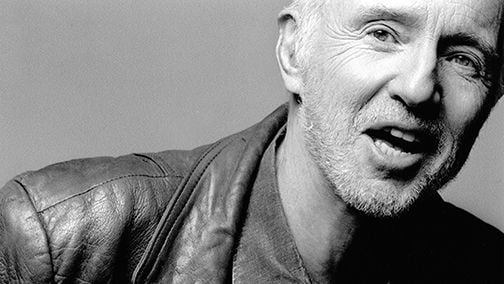

Remembering Douglas Kirkland — Influential Still Photographer and ASC Associate Member

The influential still photographer and ASC associate member died on October 2 at the age of 88.

Photos courtesy of Douglas and Françoise Kirkland

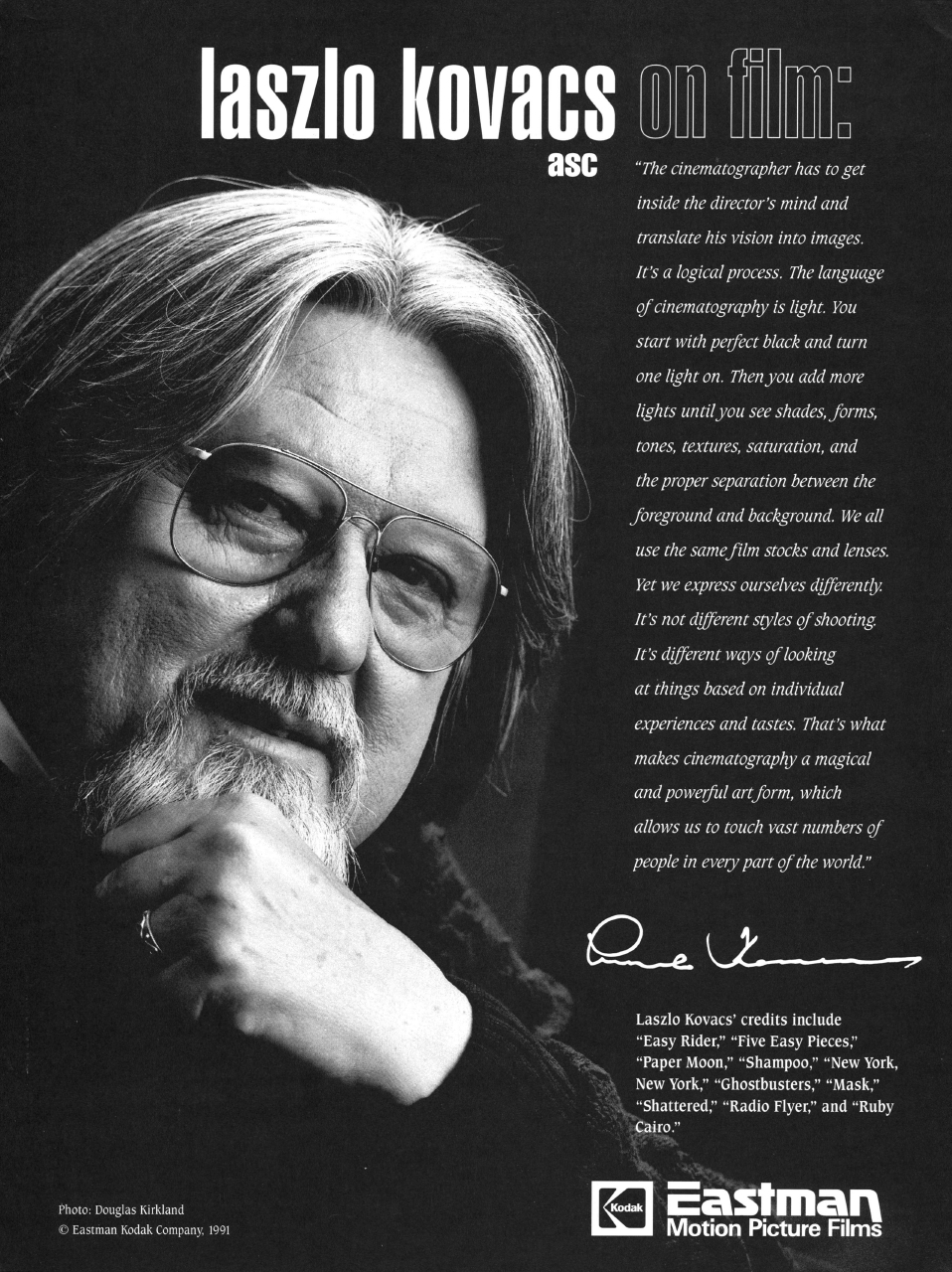

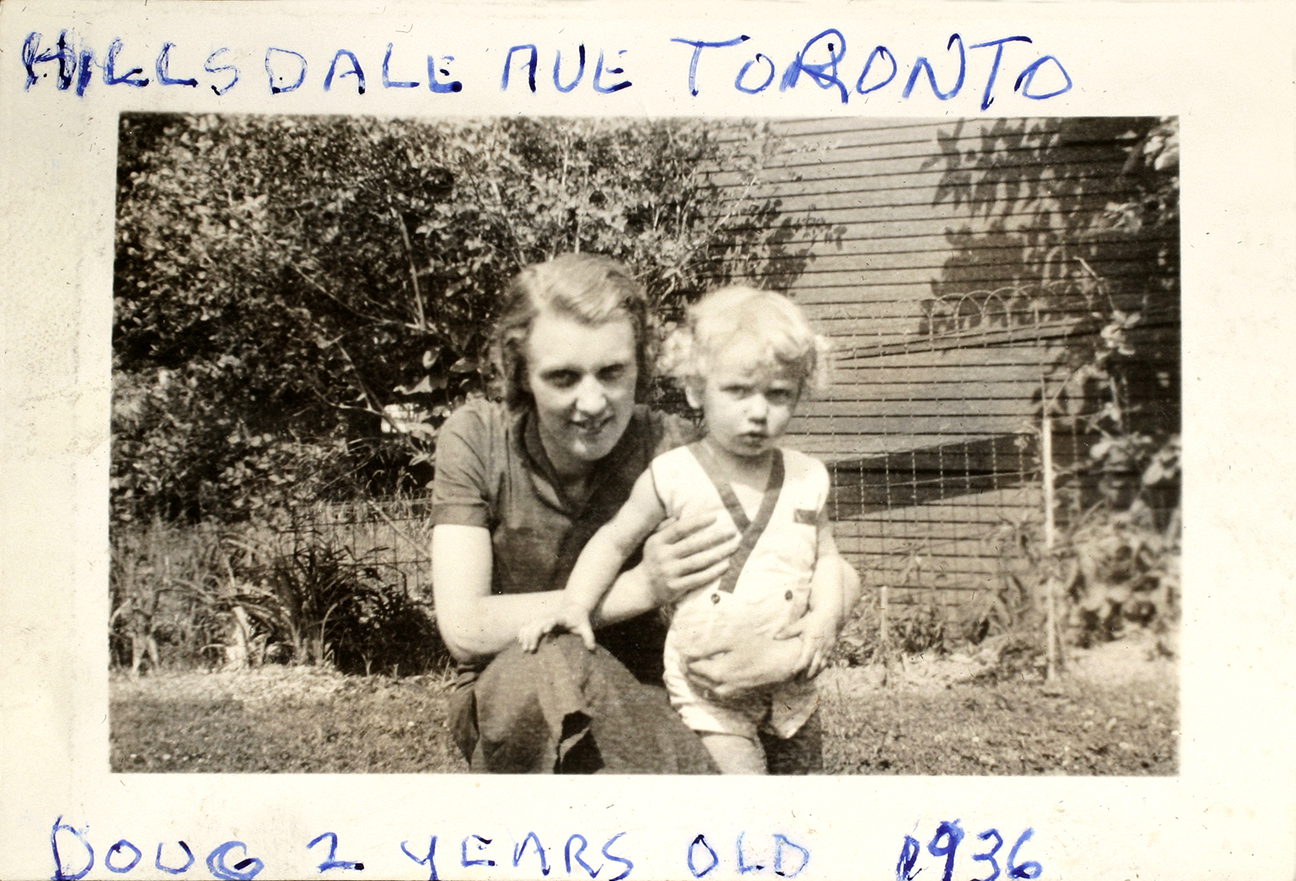

Born on August 16, 1934, in the Canadian hamlet of Fort Erie, Douglas Morely Kirkland fell in love with photography when he was a teenager. Over the years, much of his work focused on personalities who work in front of and behind the motion-picture camera, including the 200-plus cinematographers he photographed for Kodak’s long-running “On Film” ad campaign.

“Those shoots were a series of parties,” remembers Kirkland’s wife and partner Françoise, who participated in many of the sessions, which featured ASC members including John A. Alonzo, Richard Crudo, James Chressanthis, Steven Poster, Don Burgess, Gordon Willis, Joan Churchill, Nancy Schreiber, Robert Richardson, George Spiro Dibie, Judy Irola, Dante Spinotti, Darius Khondji, Ellen Kuras, Stephen Lighthill, Vittorio Storaro, Haskell Wexler, Roy Wagner, Don McAlpine, Reed Morano, John Toll, Jacek Laskus, Russell Carpenter, Eric Steelberg and Mandy Walker. “Douglas was so inspired by all of them.”

Growing up in Fort Erie (population 7,000), an uncle’s Kodachrome slides and back issues of Popular Photography sparked Kirkland’s fascination with photography. He pursued his interest relentlessly, studying photography at a vocational high school in Buffalo, N.Y., and taking any photography job he could find. His early gigs included snapping photos for Fort Erie’s weekly newspaper and serving as an assistant at a Buffalo photography studio. All the while, his heart was set on working in New York City, the heart of the publishing industry.

In 1957, Kirkland moved to New York and was fortunate enough to get a job assisting legendary photographer Irving Penn, for whom he did everything from numbering negatives to making Type-C prints. “I was learning a lot but not earning enough to live in New York indefinitely,” he told American Cinematographer contributor Jon Silberg in 2011. He needed to make the leap to a staff job, ideally with one of the glossy national magazines that were extremely popular at the time. Of course, an entire generation of talented photographers was chasing after those same staff jobs, and there were very few openings in those publications. Kirkland went back to Buffalo, where he shot in a product-advertising studio. Within a year, he was headed back to New York.

When he finally moved to the Big Apple, in 1959, Kirkland found the competition fierce and the cost-of-living high. “I found jobs at little magazines nobody had heard of,” he told AC. His early assignments included freelancing for Chemical Week, Business Week and a boating magazine. “I’d cover meetings or take portraits of executives. I also did some work for Popular Photography and wrote reports about my experiences with different equipment.”

In January of 1960, Kirkland received a call from Arthur Rothstein, the director of photography at the popular and highly respected Look magazine. There were two new openings, the first in 15 years. They tried Kirkland on a couple of stories, and he landed a staff job. “It’s hard to describe what that meant to me at that time,” he said. “I had just turned 25, and this was an unimaginable break.

“I was hired to do fashion and color,” he explained. “When I say that to people today, they think I mean ‘colorful pictures,’ but no, shooting color was a specialty then. Color photography in those days meant transparencies, and you had to get the exposure absolutely perfect. Remember, Look hadn’t hired anybody in many years, and most of them were used to shooting a black-and-white negative and having the ability to alter it in the darkroom. I was ‘the new generation.’”

The tools of the trade were also changing. Medium-format twin-lens reflexes, such as the Rolleiflex with its one fixed-focal-length lens, were still the camera of choice for many photographers of the day, and some even worked with larger, bulkier gear. But Kirkland was among a younger set that embraced shooting with 35mm Nikon rangefinders and SLRs, Canon SLRs, and the medium-format SLRs made by Hasselblad.

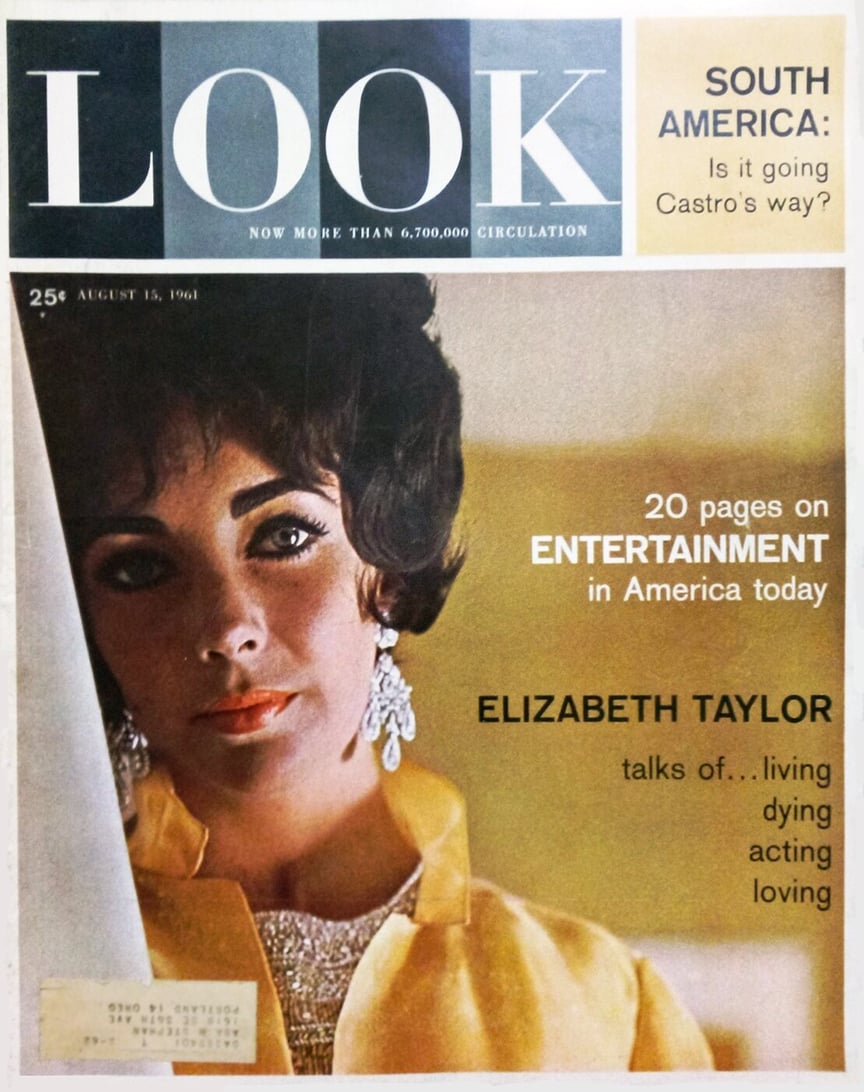

Not long after being hired by Look, Kirkland was asked to accompany a writer who was going to interview Elizabeth Taylor. The year was 1961, and Taylor was among the biggest movie stars of the day. “She had agreed to the interview but said she didn’t want to do any pictures,” Kirkland said. “My editor said, ‘You go there and see if you can persuade her to let you photograph her.’”

Kirkland was determined to fulfill his assignment. Resolute but respectful — traits he continues to bring to his celebrity portraiture — the young photographer quietly approached Taylor and told her straight out that he was new to Look. “I said, ‘Imagine what it would mean if you would give me the opportunity to photograph you,’’ he remembered. “She paused, then said, ‘Come back tomorrow night at 8:30.’

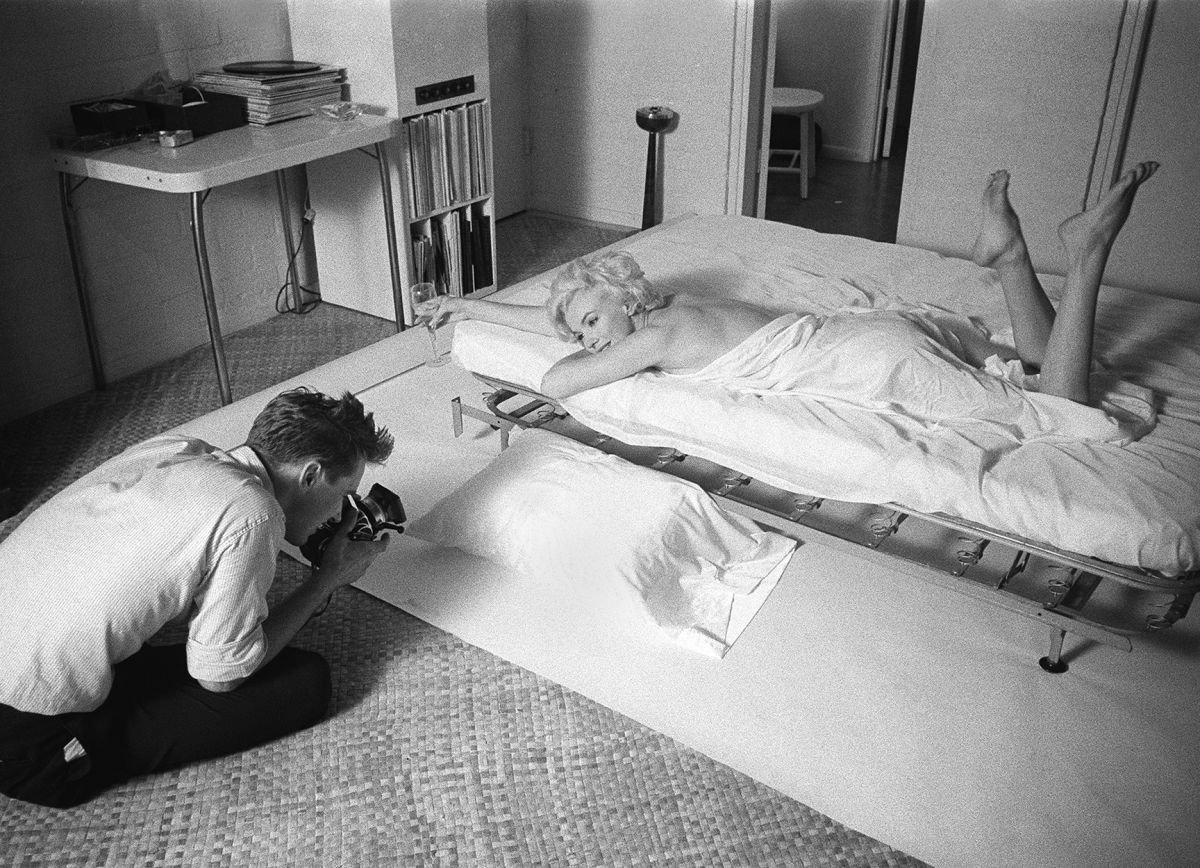

“She hadn’t had any portraits done for quite some time — the only current pictures of her were by paparazzi,” he said. “My picture of her became my first Look cover, and it ran in other magazines all over the world. It really put me on the map. By September of 1961 I was on the road with Judy Garland, shooting her for a month. That’s the way magazines did it in those days.” He was soon taking pictures of many other top celebrities of the day, including Shirley MacLaine, Marlene Dietrich and Marilyn Monroe, and this work, in turn, led to shooting on film sets.

Kirkland never worked as an official unit photographer, instead doing what was known as “special photography” for Look, Life and other publications. “It was a time when the unit photographers were generally shooting black-and-white with Rolleis and just one focal length,” he explained. “There was a certain kind of photo the studios wanted, but they couldn’t get dramatic effects or really capture the essence and the look of a film,” which is what the glossy magazines wanted. Accordingly, photographers like Kirkland were sent to the set to capture staged setups and behind-the-scenes material that fulfilled the publication’s editorial needs in a way that the unit photography of the day couldn’t.

Kirkland has done this kind of photography on more than 150 feature films, providing a preview of the film’s look to millions of readers. Some of his special photography has even made it into poster art or other key art, such as the shot he took with his Widelux camera of Julie Andrews on the mountaintop that became part of the key art for The Sound of Music, or the Kodachrome slide of Robert Redford and Meryl Streep used to advertise Out of Africa.

Kirkland loved these assignments because they took him to the center of the filmmaking process, a vantage from which he could observe the cast and crew at work. “I have a fascination with the power of cinema and watching how it all works,” he said. “I learned so much watching cinematographers work, seeing rushes and tests of lighting and lenses. I definitely have more refined abilities today as a result of watching cinematographers. I may use a strobe light or a mirror or reflector rather than the lights they generally use, but the ideas about light that I’ve learned on movie sets have affected me enormously. As a still photographer, you can use the light that’s there, maybe add some light, or even light [the shot] completely, but a cinematographer must think of a lot of things still photographers don’t need to consider, such as camera movement, continuity and where you are in the story. How fortunate to be a photographer and be so close to such work!”

He recalled observing Richard H. Kline, ASC on the set of Camelot: “The director, Joshua Logan, was an excellent stage director, and the photographic aspects of the shoot were primarily in [Kline’s] hands. I looked around at this massive stage set, all the lights and everything involved in the cinematography of the picture, and there was this guy, only a little older than I was at the time, who was in control of all of it. The Sound of Music was another eye-opener. The cinematographer, Ted McCord [ASC], was doing all this work with these huge arc lights to get the effect he wanted.”

Occasionally, a cinematographer has also adopted something Kirkland has done, which happened with David Watkin, BSC on Out of Africa. Kirkland recalled, “I was shooting Kodachrome at the time because it was just the best for clarity and saturation, but I wanted to give the images something of a sepia look. So even though Kodachrome was daylight balanced, I shot with an 85 filter. When David saw the pictures, he liked the look so much he decided to give the whole film a warmer look. That was very flattering!” Kirkland also shot “special photography” for other feature films including Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, 2001: A Space. Odyssey, Titanic, Moulin Rouge, Australia and The Great Gatsby.

Kirkland’s editors typically did not share his interest in the craft of filmmaking, instead favoring shots of celebrities, and in his celebrity portraiture Kirkland has captured some amazing candids of such icons as John Lennon, Marilyn Monroe, Peter Sellers, Marlon Brando and Charlie Chaplin. “My thing is to be honest, and most celebrities respond to that,” he said. “We all know there are a few arrogant lost souls in the business, but I’ve found that nine out of 10 are good if you are honest with them and have the right attitude. I am as at ease with celebrities as the members of the ASC are. It’s part of the job.”

When Look went out of business in 1971, the company returned photo copyrights to its staff photographers. “They were nice Midwestern people,” Kirkland described. “They felt that was the right thing to do, letting the photographers own the work they had made. Some of the work went to the Library of Congress, but all the photographers had access to it whenever they needed it. Can you imagine a company doing that today?”

By then very well established, Kirkland segued into a staff job for Look’s primary competitor, Life, and he continued working for the magazine in its many different forms until it shut down in the 1990s. Most of this work was also celebrity and entertainment-industry driven. During this time, Kirkland also freelanced for numerous other publications, tackling travel photography in Siberia, Africa and South America, and science-related work for such magazines as Geo and Omni.

Kirkland’s photography was also published in a number of books, including Light Years, Icons, Legends, Body Stories, An Evening with Marilyn, James Cameron’s Titanic, Freeze Frame, Michael Jackson — the Making of Thriller, When We Were Young, Freeze Frame: Second Cut, Douglas Kirkland — A Life in Pictures, and Physical Poetry Alphabet (co-authored by Françoise).

Over the course of his career, Kirkland was honored many times, including presentations with a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Society of Camera Operators, a Lucie Award for Outstanding Achievement in Entertainment Photography from the International Photography Awards, and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Canadian Association of Professional Image Creators. He also received an Honorary Master of Fine Arts Degree from Brooks Institute, the Award of Excellence from the Canadian Consul General in Los Angeles, and an Outstanding Achievement prize during the Canadian Arts & Fashion Awards in Toronto.

On November 6, 2001, Kirkland was invited to become an associate member of the ASC, with personal recommendations from Society members Woody Omens, Owen Roizman and Steven Poster. Noted Roizman in the announcement of Kirkland's membership, “Besides Doug’s beautiful work, he has also been a good friend to the ASC and of cinematographers in general. He has volunteered his services to us on several occasions and is always full of enthusiasm for what we do.” Kirkland was the first still photographer to receive such an invite from the Society

In 2011, Kirkland was presented with the ASC Presidents Award in recognition of his contributions to advancing the art of filmmaking through his still photography — documenting the work of cinematographers, actors, directors, and other motion-picture professionals. When Kirkland’s wife and business partner, Françoise, got the call from then-ASC President Michael Goi about the honor, she first assumed the Society wanted her husband’s help with a photography project. “I gave him the phone and went into another room,” she told AC. “When he hung up, he came in and said, ‘I have something to tell you.’ He was so serious I thought it must be terrible news! But he was just that moved about receiving this recognition. And he is not what you would call an overly emotional person.”

“For me,” said Douglas, “the ASC is the singular heart of the industry. I know so many of the members, and so many of them have done amazing work. There is no film without them — at least, no viable film.”

October 2, Kirkland died peacefully at his home in Los Angeles, in the company of surviving family including Françoise and his son, award-winning director and ASC associate member Mark Kirkland.