SPONSORED BY: ASC Master Class

ABOUT THE PARTICIPANTS

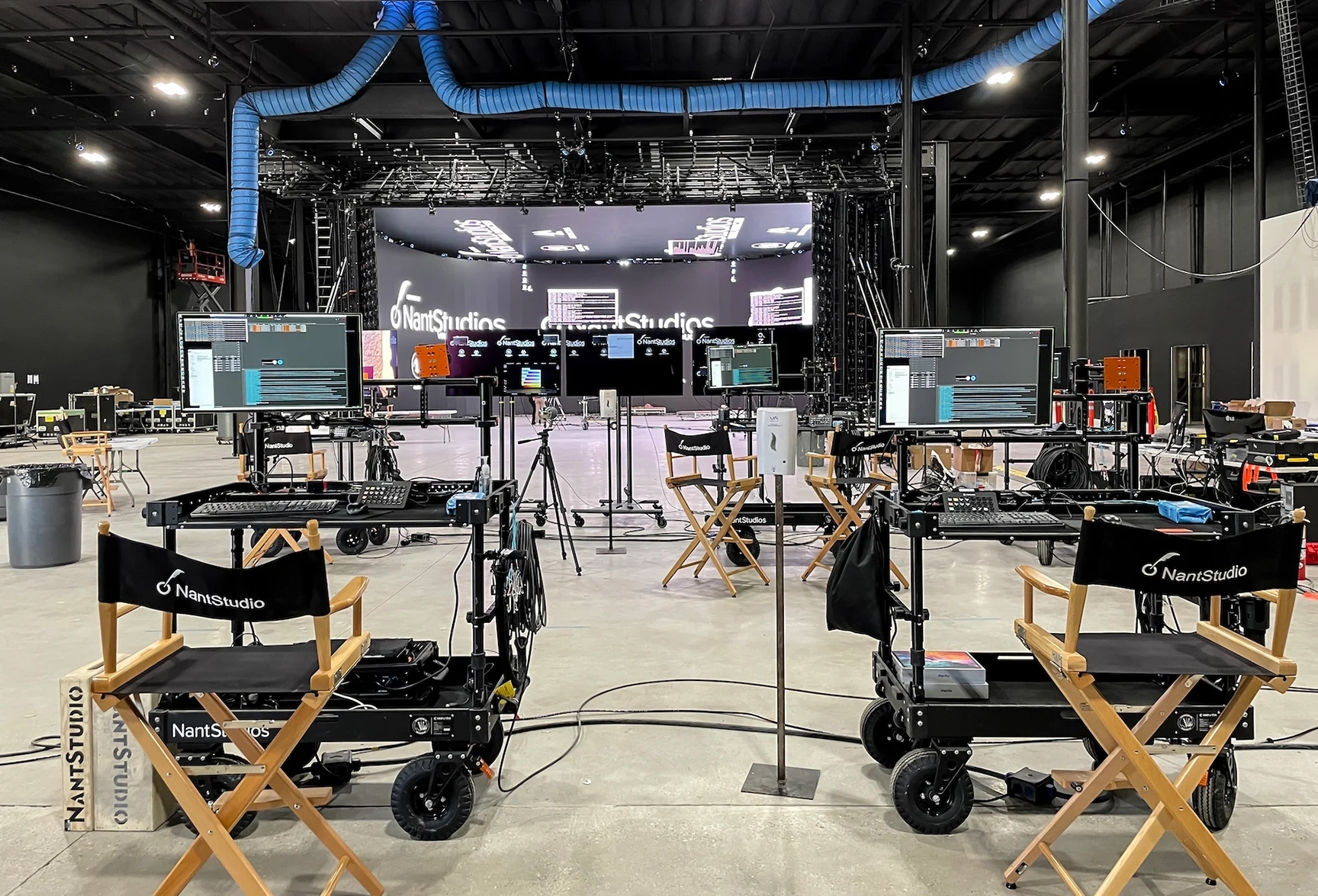

CONNIE KENNEDY

A veteran film and TV producer, Kennedy has consistently been at the forefront of emerging technologies to facilitate both physical and virtual production. She is currently the Director of the Los Angeles Lab at Epic Games, where she is responsible for education and industry adoption of Unreal Engine in film and television, working with top studios to leverage real-time video game engines in innovative ways on projects such as The Mandalorian and Westworld. She previously co-founded Profile Studios, a pioneer in the area of virtual production with credits including Star Wars: Episode VII: The Force Awakens and Avengers: Endgame. Through Profile she also served as virtual production producer for Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s VR experience Carne y Arena, which was awarded a Special Achievement Oscar. Connie is most excited about the on-set collaboration afforded by game engines and high-end LED walls, which can bring the magic of VFX directly to the cast and crew while filming.

NOAH KADNER

Kadner is the Virtual Production Editor at American Cinematographer and author of the Virtual Production Field Guide series for Epic Games. He also hosts the Virtual Production Podcast. Noah is a seasoned industry thought leader. His partners include Epic Games, Apple, and ROE Visual. Noah also has extensive production and postproduction experience in film, broadcast, streaming and virtual production.

TRANSCRIPT

Iain Marcks: Connie and Noah, welcome to the American Cinematographer Podcast.

Connie Kennedy: Thank you. It’s wonderful to be here.

Noah Kadner: Very happy to be here.

Iain Marcks: Connie, I want to start by asking you what kinds of virtual production innovations are happening at the Epic Games LA Lab?

Connie Kennedy: Well, I think mostly what we’re involved in at the moment is trying to develop the Unreal Engine with features that are the best they can be for ICVFX. And that process depends a lot on the different productions that are in progress and the feedback that we get from them. And then as we get feedback from them, we're constantly fixing bugs and coming up with new ideas and improving the way in which we’re both creating content and also operating stages. It’s really a community effort is probably the best way to say it.

Iain Marcks: Now, what kinds of productions do you see coming through the lab?

Connie Kennedy: You know, the lab is really set up for testing and R&D. We don’t really bring in productions per se. But one thing that we are doing is setting up workshops, so that we can bring people who are in production together as a community, and we can listen to what their experiences are. And we can talk to them about the latest innovations that we’re involved in, and then we can talk to them about how they might integrate that into their own workflow.

Iain Marcks: It seems significant that Epic is a video game company innovating in the motion picture medium, and that games and motion pictures would intersect was inevitable, but exactly how was less clear. What was the turning point in your estimation?

Connie Kennedy: If I was to pinpoint a moment and talk about a project, it would have to be The Mandalorian. That was a moment when we brought people in the film business in visual effects with ILM, Lucasfilm, and Epic Games, Lux Machina, Fuse. I mean, there were so many people that came together at that moment. And it was really exciting, because, you know, I have to say that no one really knew how it would go. But what was wonderful was that everybody was willing to give it a try.

And the studio was willing to put the money towards trying it. And I think if I was to pinpoint a time, that would be the moment, but really, when I look at virtual production as a whole, and the way that tools in gaming began to be intersected into the workflow for film and television, it was really farther back from that it was more to do with what we were doing with Avatar, what we were doing with World of Warcraft, Avengers, we were doing something called simulcam. And that’s when we started to realize that, hey, you know, we can put virtual environments, virtual characters, and live-action together. And then it became important to figure out how do we all work together and make decisions in real time. And I think, you know, in the gaming workflow that people were used to, they were used to looking at the environment and using virtual characters and virtual environments and making decisions together. But it wasn’t the case in film and television. So this became a new process. And I would say, it’s really with those kinds of projects that we began to realize that we were embarking on a whole new era. And then I think, with The Mandalorian, and the integration of LED walls, which have been used for years in broadcasting, you know, all of a sudden, we were in a situation where we had the ability to render more quickly using hardware, graphics cards that could render composite imagery in a way that we’ve never seen before. And we had a game engine where we could composite all of these elements in real time, we’ve been working on the ability to make decisions about lighting, all of these things continue to evolve, and make it possible for it to be a faster and more effective real time workflow.

Iain Marcks: You mentioned the term ‘real time’ a few times. And it seems that a key component of what makes virtual production work is that it’s in real time. What is the significance of this development?

Connie Kennedy: The significance is the way it informs collaboration. I think, you know, the more we can have people who used to be siloed, in whether it was with postproduction, or people who are in production, who aren’t necessarily able to be there during production, especially production designers, people in the art department, people who are normally not normally but traditionally involved in preproduction and prep, and now they’re in real time, making decisions with people who are actually involved in the production. And we’re bringing what used to be punted to postproduction into the preproduction process and also into production. So what happens is, all of a sudden, you have everyone able to make a decision about lighting, blocking, performance, the look of the entire picture, you’ve got all the important people to that decision making process on the stage standing there in real time making those decisions together.

Iain Marcks: Noah, there seems to be some confusion about what virtual production actually is. In-camera visual effects, or ICVFX, is a key element, right, working on a volume with LED walls. It’s also more than that. Can you elaborate?

Noah Kadner: Yeah, I mean, I think obviously, in-camera visual effects with LED walls has been extremely popular over the past few years, thanks, in no small part to successes of shows like The Mandalorian. And it has kind of led to this sort of equating that term to mean virtual production, when in fact, it’s actually a subset of virtual production. And that as a term is something that’s been around for well over a decade now, coming up, actually coming up on 15 years, originally coined during the production of the movie Avatar back in 2009, to essentially refer to any sort of activity in which physical filmmaking and digital visual effects were happening simultaneously, as opposed to you film a green screen. And later, you’ve kind of put the background in and postproduction, taking guesses while you’re filming it, what it's actually going to look like. It's the idea that there’s some aspect of the filmmaking in which that post process comes into the live action workflow. So some other examples of virtual production, in addition to in-camera visual effects are things like simulcam, where you might be superimposing using real time animation tools, some sort of digital environment on top of the live camera feed that that cinematographer is looking at. Some of the other areas are just kinds of visualization like previs and postvis techniques, just all these ways in which we’re taking these real time tools and using them to kind of create provisional imagery that assists the live action production, things like motion capture, you know, again, coming back to Avatar, that was kind of their big thing was mixing together, motion capture, simulcam, and essentially having a really solid preview of the movie that they were filming, as they were making it with a lot of the elements that would be added later in postproduction kind of brought forward at least in sort of a proxy way. So you know, I mean, it’s one of those things it’s been hiding in plain sight in the movie business for years, it just suddenly became very popular. And I think that may be why people are equating those two terms. But yeah, I mean, if we could set the record straight, virtual production is sort of the spectrum of which in camera visual effects is just one flavor.

Iain Marcks: Where else is virtual production being employed outside the theatrical and television based mediums? And which industries are driving the biggest innovations in virtual production?

Noah Kadner: I mean, I could, I could say a few words. I mean, obviously, Connie knows this world better than anybody, but this happens to be very fresh in my mind, because we're doing a couple of these stories for an upcoming issue of the magazine. But it seems to me and you know, maybe you could comment on this as well, kind of, but it seems to me like things like concerts, award shows, live sports are really kind of driving people in the sense of, there will be some kind of virtual production technology that's used in a way that is not necessarily how you might use it in filmmaking, but has potential, let's just say like, for example, you know, LED screens as something you would actually film in front of a camera that's been around, if you watch shows, like, you know, Sports Center, or you know, anything of that sort of genre, you will have seen a stage that probably or even, you know, just regular news broadcasts, you will have seen a studio that might have some LED screens on it to be used as displays backgrounds, what have you, they don't, but they were never meant to be realistic. It was always meant to be like, here's a really beautiful-looking, big display in the background that has some bearing on what it is we're broadcasting. And that ultimately, I think, at least validated the possibility that if the screens got to the point where the resolution was high enough, and the quality of the imagery that has been generated was sufficiently realistic enough that you could actually use it in place of something like a greenscreen, or in place of something like a miniature or in place of something like a matte painting scene. And so I feel like that's still happening today, there's a number of new stories that I'm tracking, that are using even more cutting edge virtual production techniques for broadcast use, that may not necessarily look realistic or have an application to filmmaking per se. But, you know, at first sight, but I think have a lot of potential. So I don't know, does that jibe with your experience, Connie?

Connie Kennedy: Oh, yeah. And I think what I would add to that by saying that really these visualization techniques, which is really what we're talking about, we're using them for all different purposes. So it may be that we're using them for augmented and virtual reality with sports, but which is what you're describing, all using different photographic backgrounds, so that we can create the illusion of a car, going to multiple locations within minutes. And you know, illusions like that, that are really cool for advertising and that kind of thing. But I think what's really exciting is the way these tools are being used, in order to visualize a more sophisticated project, where you need to figure out where you're going to put your time, your money, your resources, and how are you going to know how to do that without being able to see something in advance. And I think the way that these tools are being used with production designers, and other departments, whether they're prepping an event, a theme park, a movie, a television show, or a game, all of these tools can be used in the same manner, to be able to help create the roadmap, and create the style, and the look, and all of the things that can otherwise be really time consuming, and expensive, and prohibitive, depending on your budget. So if you're able to get a fantastic-looking image, and really drive a story point, and be able to pitch that to a studio and say this is the way this movie is going to look, this is how the characters are going to look inside this environment, this is how it can be integrated into a fantastical setting, and then a realistic setting, and this is how it will all look together, those visuals go so far to being able to sell your idea in a way that you wouldn't be able to do otherwise. And I think that is a really, really exciting aspect of the way these tools are being used. And then I would also go as far as to say that there's all kinds of things in the future that we're headed for, with these tools in the sense that we're going to be able to create a film that is like a passive experience, that will become a more interactive experience. And I think that is a really, really exciting prospect for the future, because of the way in which we're developing tools that allow for us to make these different kinds of immersive experiences simultaneously. And I think that's going to, you know, depending on the way in which we distribute those experiences, that's going to be leading us into this kind of transmedia world that we still have yet to define.

Iain Marcks: Is that something that you're working on at the innovation labs, is not just the virtual production, but also the distribution of this transmedia?

Connie Kennedy: I wouldn't say necessarily that we're working on distribution directly. We certainly are with Fortnite. That is, you know, that's our domain. But there are a lot of projects, of course, that we wouldn't have any control over exactly how the distribution would be, but we can certainly help drive that distribution with the tools we're creating.

Iain Marcks: Well, distribution, I guess, for an immersive experience, would like, implementation be a better term?

Connie Kennedy: Oh, yeah. I'm, we're involved in so many industries, we have tools that are being used with architecture, an automotive, fashion, all you know, various types of AR and VR experiences. I mean, it's honestly exploding right now. Because people are discovering that these tools, it's so wonderful for being able to create experiences that we wouldn't have otherwise, if you were just rooted in, in the real environment.

Iain Marcks: What are some of the ways that cinematographers can take advantage of virtual production beyond what we've just already discussed here? Like you mentioned, simulcam. What's the potential, let's say for virtual cameras and lenses? Are we going to see software-based film stocks? Or real time virtual optics? You know, is there a place for light field photography in virtual production?

Connie Kennedy: Given that Noah is a cinematographer, let's say, Noah, I'd love to hear your point of view. I mean, we’re certainly developing tools for lighting. It's one of the most important things that we're doing with the engine right now. AndI think it would be really interesting to hear from you, Noah, about how you might have seen this in production right now, and how that's working for you.

Noah Kadner: Yeah, I mean, you know, obviously, cinematography at its core is, is kind of the collection of imagery using some kind of an apparatus. I mean, that's something that hasn't changed for well over a century. What has changed is what that apparatus or that, you know, that motion picture camera is capable of doing versus capturing a series of still images that we project back and you get a persistence of vision, and it appears as though you're watching motion. Does that mean, we're talking about things like Avatar, where they're filming, they're not capturing imagery, but they're capturing motion, and then transferring that motion into the movements of digital characters and presenting that in 3D and also high frame rate. I think as we continue down this road, we're going to see more things coming around that allow us to experience stories in ways that go way beyond that sort of 2D presentation. You know, whether that means we'll all be wearing headsets, whether that means we'll all be wearing AR glasses, that remains to be seen. That technology has been around for a while now, too, and no one has been able to really popularize it in a way that makes the mainstream want to go check it out. When Avatar came out in 2009, the first Avatar, it seemed like we were on the verge of all movies being shot in 3D because that movie was so successful in taking advantage of that medium, and for a brief time, a lot of movies were being shot in 3D. But I think there was some pushback on the part of a lot of filmmakers that it added so much additional technical hassle for not really a big difference as far as the way the audience would experience it. Because ultimately, a lot of people weren't even seeing these movies in 3D anyway, because they either didn't feel like putting on the glasses, or it wasn't available in the area or whatever. And so it seems like there's going to be opportunities to tell stories in completely new ways that a cinematographer’s sort of artistic eye will absolutely still be very useful for. It's just a, it's kind of, I think the cinematographer has always been meeting the audience wherever they end up being, and so as we see these new technologies and ways to participate come down the pipe. You know, like, I spent a good chunk of this holiday break playing this game called The Last of Us with my son, which is all about, you know, this insane situation of people trying to survive a kind of post-apocalyptic world. And it's, but it's really, you know, it's the way it's presented is really very cinematic. And I wasn't even actually bothering to control it. My son was playing it the whole time. But we, you know, my wife and I were just watching him play. And we were really into it as much as you would be any movie. And you could see there had been a lot of time spent on that presentation to make it look striking and cinematic, and not just kind of a flat and, you know, boring presentation. So, yeah, I can only see those opportunities continuing on, but the artistry that goes into eliciting an emotional response through the way something is depicted is always going to be, you know, important, I think.

Connie Kennedy: Yeah, the way in which the challenge becomes integrating virtual and real environments and people and characters and inanimate objects, and being able to blend this in a way that if certainly, if you're trying to do something that's photoreal and you're using ICVFX, and you're using an LED wall, all of those challenges have to do with the way in which we're interpreting what it should look like and And so, you know, it's interesting when you talk to different cinematographers, that it's not a kind of paint by numbers process, it's not like, Oh, here's the formula, this is what you do. There's still a lot of room to make decisions based on your own artistic sensibility. And that's both in the computer and on the stage, physically. And that it's really interesting to watch a team trying to work with that, because what I've discovered is that people aren't necessarily looking for the perfect solution. They're looking for something, they're looking for the imperfection that actually makes it work. And that's something that's much more subtle, and consequently, difficult to communicate, difficult to collaborate around, and difficult to ultimately execute. So but it's but it's, that's what makes this so exciting, is because you're watching all of these different creative people work together to try and explore what this is and how it works, and how to make it benefit the story as best they can. So I think we have a long way to go, but I think we're, you know, we're quickly getting through enough projects where we are starting to share our experiences, and realize what's working and what's not.

Iain Marcks: You mentioned, Connie, that one of the things that you're working on right now is lighting. And I know that with the big Unreal Engine 5.0, 5.1 update that a lot of upgrades were made to the way the engine renders light, can you talk a little bit about those developments in the way that light has evolved in this environment?

Connie Kennedy: I think probably the simplest way to put it is that we're trying to automate as much of this as we can, you know, I think when you're when you're trying to make changes, that are responding, that are changes that are responding to what you're doing physically and what you're doing virtually. And you're trying to blend this together, and replicate what happens in the physical world, in the virtual world. It's complicated. Because there's a domino effect. Every time you move a prop, every time there's a reflection on a window. Every time there's something that happens on water, or the glint of an eye or the way light falls on someone's face, all of those things have to be coordinated between the virtual and physical world. And so we're working to develop tools that will make changes based on certain physical principles, and that takes a long time. So we're in the process of developing tools that will make that simpler and faster and more accurate. And so we have 5.1 is the version that just came out in the interim with Lumen, and then Nanite, and 5.1.1 will be even more refined, and by 5.2, will have even more tools. But this is constantly evolving, and it's something that we discovered, depending on the environment, the virtual environments that people are working in, it presents new problems and requires new solutions. And so we're listening to people's experiences every day, and trying to respond as best we can, with changes to the tools and new developments with the features that make this easier and better.

Iain Marcks: Is there a correlation between let's say, the learning curve of understanding how the Unreal engine works and the adoption curve? Like do you spend a lot of time having to explain to people who maybe don't have a lot of experience with video games, like what a game engine is, and why it's significant that it works in real time, you know, and that you're able to coordinate the virtual and the practical using this technology.

Connie Kennedy: You know, the word 'game' is sometimes the issue. I think people who don't who aren't aware of what a game engine is, I think the word 'game' is a little bit distracting at times. But then when you when you do understand that what the game engine is really doing that it's actually something that's allowing us to composite different elements together in one, you know, final render, then people start to realize, Oh, all these things, they used to be segregated, we're now talking about looking at it together as a whole. And when you begin to understand that is what's so exciting about this, that's what's making it possible to use virtual elements in real time, and be able to make changes in real time. You know, you want to move a rock or change the position of a tree, you want to maybe change the time of day, all of those things become a really exciting option when you're in the middle of a creative process. And I think when people begin to realize this is what is a new experience for filmmakers, then they start to understand how to make strategic decisions about when to use this, because I think what happens is that people think that this is going to replace everything that we're doing in any creative process. So we're never going to go on location, again, for a movie. Well, that's not the case. This is adding to our toolkit. This is giving us the opportunity to create experiences, and add story points that you wouldn't be able to do otherwise. Because now you can create worlds and experiences and add them to the story in a way that you never could before.

Iain Marcks: We've talked about The Mandalorian, and we've talked about Avatar in passing, but what are some of the ways that an independent filmmaker can take advantage of virtual production?

Noah Kadner: Well, I mean, it's exactly that, you know, I've actually interviewed a number of filmmakers who didn't necessarily have an amazing amount of resources, but found ways to leverage these tools, either by making a project say, entirely in game engine, or finding a way to tap into some aspect of the game engine’s capabilities, like maybe making a movie using mocap, or using it to create visual effects for their film. But yeah, I mean, that, to me, that is one of the most exciting pieces of it is, first of all, you're talking about software that's free, because its bread and butter is making video games. So you're kind of getting, you're kind of getting a free ride on the coattails of the videogame industry by using this as a filmmaking tool because they've been generous enough to give it away for free. And it really does stack up quite impressively to a lot of other tools that are quite honestly, quite prohibitively expensive to someone working at the indie level. So terms like democratization do get thrown around quite a bit, but I think in this instance, it really is appropriate. Because if you have access to a computer that can play video games, you pretty much have everything you need to make a movie exactly the way you want to imagine it. And so taking that against, say, 20, 30 years ago, where the means of filmmaking, where you got your hands on a film camera, and maybe you got some short ends of film somewhere and you know, scrambled together enough cash to develop it and process it, you still have a long way to go before you could make something that would stand next to the Hollywood sort of standard of filmmaking. Whereas today, just for the price of a computer, and using the software, you could easily remake Star Wars if you really wanted to, or something along those lines. without breaking a sweat. It's just you know, it's comes down to just raw talent and ambition, which is very exciting, because yeah, filmmaking in general is such an expensive endeavor that it is a little bit rarefied, and into who actually gets the opportunity to make movies. So by taking that away, and sort of providing this open possibility, hopefully, we'll see, you know, more and more interesting stories being told by people that might never have had the chance to even consider themselves filmmakers, just because the lift to get to all those resources that used to be required was so high, they just kind of gave up and did something else entirely, or maybe wrote books or whatever. So that, to me is the most exciting part. And, you know, I think you're gonna see that happen more and more as the tools become even easier and more accessible to us. Hopefully, you know, the tent will continue to grow greater and greater and more people will come in.

Connie Kennedy: Yeah, and I would add to that, Noah, that we're creating a very high quality level of content that's also available to people for virtually no money. And then you can either use it as is or build on top of it. But you're starting at a point where it's optimized to a level that used to take months to create. So that's giving independent filmmakers the opportunity to create something really great as well. So you've got environments, and now we’re, you know, introducing MetaHumans into the engine. Pretty soon, everything will be there, everything you need will be there in order to offer people the opportunity to make all kinds of different stories with marketplace assets that they have access to. And I think I think it's, it's only just beginning to be something that's accessible to everyone everywhere. And also, people are able to work together and collaborate, no matter where they live. So when we're also not restricted by a physical location. So there's a confluence of a number of different changes that are making it possible for people to make very high quality content on an independent level.

Iain Marcks: Right. When you say MetaHumans, we're talking about the high resolution, very realistic-looking human models.

Connie Kennedy: Yeah, the exciting thing is that they're completely rigged, they're ready to go. And that's a revolutionary change. So we're going to begin to see all kinds of really exciting changes with what the MetaHuman initiative is bringing to the attention.

Iain Marcks: What is virtual production not good for? It's not going to solve all your problems. And like you were saying, it's not going to replace location shooting, right?

Connie Kennedy: It doesn't need to replace anything, the most important thing is to choose the right tool for the job, I think is what it comes down to. If you have a story, where the location just doesn't exist in the real world, then of course, you're going to need to do something else. And if you decide that you don't have the money to create photo-real environments, or photo-real characters for your story, then you can choose to do it stylistically, in a way that might make it less expensive and less labor intensive. There's a variety of different ways to represent your story visually, around whatever budget you have. And that's the challenge. That's what's exciting. I mean, you can see people who create equally emotional and gripping stories with all different types of visual representation. So I think virtual production is giving people the opportunity to tell their stories in a myriad of different ways.

Noah Kadner: Yeah, as we've seen, and you know, been celebrating over the past few years, if there was anything I would say it's not good at, it's not good for the kind of filmmaking style that's very off-the-cuff, in the sense of, if you're a kind of filmmaker who likes to show up in the morning, and sort of, like, suss it out as you go, and like, Oh, let's go over here, and let's go there, you could find yourself not so happy in one of these setups, because it's like, the preparation that goes into a successful, especially something like in-camera VFX, it cannot be overstated. So, you know, the more that you can visualize how you're gonna do something, plan, and have everything prepared so that when you get to the day, then you have that flexibility. I mean, you look at you know, we were talking about Avatar, you look at Avatar 2, that's been in prep for, you know, almost a decade really. I mean, Cameron has obviously started thinking about it the instant he finished the first one, and it's taken him all this time. And so, you know, you see that movie in two plus hours of, what is it, almost three hours, and it goes by really quick and you’re like, Oh, it feels really spontaneous and off-the-cuff. And it's like, no, this every bloody frame of this movie was agonized over for years to make it look that way, which you know, is his specialty. But that would be the one, or it's like, be prepared.

Iain Marcks: One thing we haven't discussed is iteration is something that virtual production is really good for, having the shot there that you can iterate over and over and over and over and over again until you get it perfect.

Connie Kennedy: Yeah, there's, I mean, that's a wonderful thing. It's also a dangerous thing. Because you can put too much time into something that may end up not even being in the movie. So you know, there's a danger in that to a certain extent, I think. You know, what Noah is pointing out is that it's really important to have a clear roadmap and have an idea as to how much prep time is required. And I think given that a lot of this is new to people, sometimes that is really difficult to assess. And it couldn't be more important. It's the difference between success or not, whether or not you're allowing enough time to create the content, and whether you're locked in. Because if you start making changes, once you've gotten into production, and you're not ready with those assets, and you've got a crew that is ultimately going to be standing around waiting for that, that's not going to be a good situation. So, you know, I think this is probably one of the biggest challenges right now is that people, you know, previously have been making movies often without even writing the script as they're shooting, and that's not a workflow that would work when you need to have these assets ready to go well in advance. And that means approvals across all departments, and budget approvals across all departments.

Iain Marcks: Do you think that's something to work towards for the future? So that filmmakers who do— because, you know, we talked about routine solutions, you know, and there are no routine solutions, especially with filmmaking. And so do you think that eventually, someday, working within the Unreal Engine, working with virtual production will allow filmmakers that kind of spontaneity?

Noah Kadner: I mean, I personally think— I mean, it's there already. I mean, definitely, if you have an environment that's been created, with some flexibility built into it, for example, you know, something where you didn't just build one view, but you built the view that's technically behind the camera. Because if somebody is like, Let's do reverse shot, you can just be like, No problem group. And I think that, and I've already seen this, I've already seen tools that are starting to scratch the surface, this was an area that we're going to collide into, at some point, inevitably, is kind of things like AI and generative art. I suspect, you know, within a few years, it will be very conceivable that you could be on a set in one environment and just say, wouldn't it be great if it was this instead? And it'll be good, it'll just be there. Like, there won't be there won't be somebody modeling that there won't be somebody like, Oh, let me rearrange that the computer, and the application that you're working with will ultimately just understand those kinds of natural language problem prompts, and be able to, to vastly alter the environment as you go. And so yeah, I mean, right now, we're in that moment where there's more of a heavy lift to build those environments and make those assets. And there's a lot more people involved, there's a lot more work involved. But I suspect that process will be streamlined and greatly assisted by what we're already starting to see a lot of in terms of generative art, just because computers will be getting better and better at just understanding requests made not using their language, which has a lot of kind of esoteric commands and things like that, but just will understand exactly what you're describing and just do it.

Iain Marcks: It feels like we're still accelerating through this adoption curve on the track of virtual production, but we haven't hit the straightaway yet. Other than the LA Lab or American Cinematographer, what are some of the resources available to filmmakers and creators who want to learn more about virtual production or maybe even take the wheel and help drive the technology forward?

Connie Kennedy: You know, I think there's a number of different schools and we're supporting them, who are developing different types of virtual production curriculums. And we’re starting to try and connect the dots between all of them so that they can collaborate on what it is that they're developing to teach. And so I would say, a number of different companies: SCAD, Pixomondo, Final Pixel, Disguise, Vū. You know, there's a number of companies that have set up great academies, and they're building a wealth of material. The [Visual Effects Society] is working on a really nice glossary, and that's helping people understand what's meant by all the new terminology that's coming up. The Software Academy, there's a number of different organizations that are working on helping people to collaborate around all this new information that is kind of being curated by all these different schools and associations. So I think something like the LA Lab magazine, or the American Cinematographer magazine, we're all trying to help people understand where to go to find that information.

Iain Marcks: Noah, any anything to add?

Noah Kadner: Yeah, I mean, filmmaking has always been a very collaborative effort. I mean, it's extremely challenging. Even if you are this sort of auteur type, it is very challenging to make a film without involving other people in some way. And so there has always been a lot of back and forth as far as sharing of techniques and, you know, cutting-edge sort of workflows, which is something we obviously cover constantly in American Cinematographer, you've got people at a very high level kind of breaking down exactly what they've done in a in a finished product, so that you can possibly emulate what they're trying to do, or at least I'd better understand what it is you're looking at. And with virtual production, I've never seen that taken to such an insane level of openness. All this stuff, it’s almost like this fully-formed industry appeared overnight, and people are just trying to understand it and kind of get their heads around it, because they want to use it because they are impressed with its capabilities. And so, yeah, it seem way above and beyond what I'm used to seeing as far as how much people are willing to share their time and, you know, explain to others what's working. And so yeah, it's a great opportunity right now, I mean, if you have the slightest interest in this stuff, there are so many places to go to learn more. And there's so many ways to get hands-on experience. You know, that as far as breaking into an industry like filmmaking, there's, to my humble opinion, never been a more fertile time, just because there's so much interest around it. And it seems like there's still this major gap in terms of people that have that unique combination of skills that allows them to be capable of doing in-camera VFX, you know, at a level that's demanded of by these productions, and so that, you know, there's a strong motivation, and a lot of the companies that Connie just mentioned, to bridge that gap and train people up as quickly as possible. So if you want to surf the wave, you know, I sound like I'm selling the Kool-Aid here, and in some ways, maybe I am, but it's a great time to get into it, I would say more than I've ever seen in my whole career.

Connie Kennedy: And I would also add to that to say that what's really exciting is that it's global. So this is something that’s happening everywhere at the same time. And what's wonderful is it's giving an opportunity for people to tell stories that are specific to a variety of different cultural contexts, which makes it really rich and interesting. And I can't wait to see what people come up with.

Iain Marcks: It's a super exciting time to be a filmmaker, and Connie and Noah, I really appreciate you coming on to the podcast and talking about it. And just thanks so much for being here.

Connie Kennedy: You're welcome. Great to talk to you.

Noah Kadner: Oh, yes, my pleasure.

American Cinematographer interviews cinematographers, directors and other filmmakers to take you behind the scenes on major studio movies, independent films and popular television series.

Subscribe on iTunes