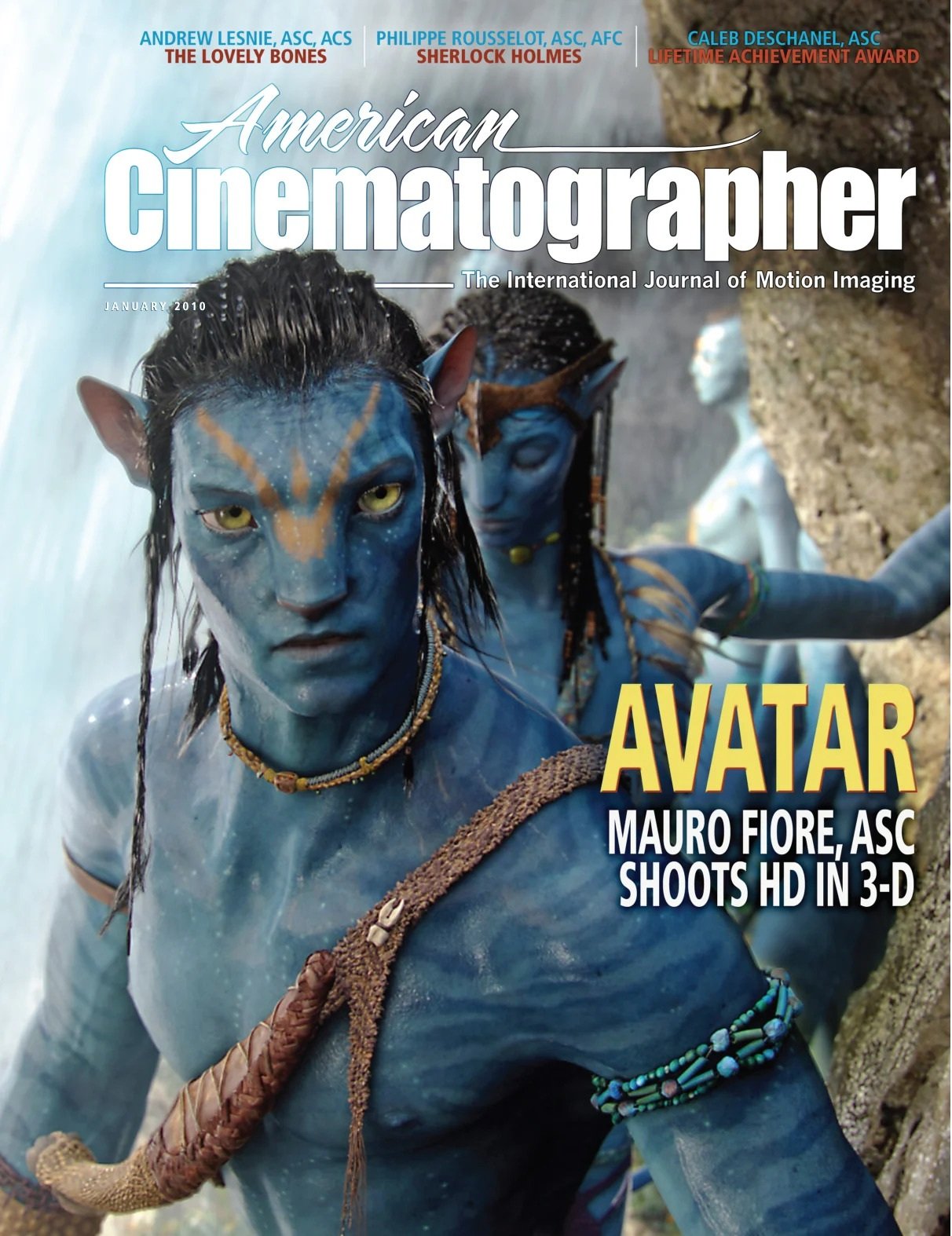

Conquering New Worlds: Avatar

Mauro Fiore, ASC helps James Cameron envision his 3-D science-fiction adventure that combines highdefinition video and motion capture.

A decade in the making, James Cameron’s Avatar required four years of production and some major advances in cinema and 3-D technology in order to reach the screen. Cameron spent much of the decade exploring the 3-D format on the hi-def Imax documentaries Ghosts of the Abyss (AC, July '03) and Aliens of the Deep (AC, March '05). On both of those films, he partnered with Vince Pace, ASC of Pace HD, who adapted two optical blocks from Sony’s F950 CineAlta HD cameras to create a 3-D camera with controllable interocular distance and convergence.

With an eye on Avatar, Pace and Cameron refined their 3-D digital camera system considerably over the course of their collaborations. “A feature-based camera system needed to be quieter and react more quickly to interocular and convergence changes than our original system did,” says Pace. “The original system was perfectly suited to Imax but a bit more challenged for a feature, especially a James Cameron feature!”

The result of their refinements is the Fusion 3-D Camera System, which incorporates 11 channels of motion: zoom, focus and iris for two lenses, independent convergence between the two cameras, interocular control, and mirror control to maintain the balance of the rig (especially for Steadicam). The system can also be stripped down to facilitate handheld work. “We also devised a way to have more control over the interocular distance — on Avatar, some shots were down to 1/3-inch interocular, and others were all the way out to 2 inches,” Pace adds. “With all of those elements combined, you’ve got an intense 3-D system.”

The Fusion 3-D system can support a variety of cameras. For Avatar, the production used three Sony models: the F950, the HDC1500 (for 60-fps high-speed work) and, toward the end of production, the F23. All of the cameras have ⅔" HD chips and record images onto HDCam-SR tape, but on Avatar, they were also recording to Codex digital recorders capable of synced simultaneous playback, allowing the filmmakers to preview 3-D scenes on location. “We used the traditional side-by-side configuration in certain circumstances, but that’s too unwieldy for Steadicam work, so for that we created a beam-splitter version that comprised one horizontally oriented camera and, above that, one perpendicularly oriented camera, forming an inverted ‘L,’” says Pace. “However, there was a change in balance when the camera shifted convergence or interocular distance, so we created a servo mechanism with a counterweight to keep the camera in perfect balance. This Steadicam configuration also allowed us to get the interocular distance down to a third of an inch. There was a tradeoff: we lost ⅔ of a stop of light through the beam-splitter’s glass. And for really wide shots, we needed a larger beam-splitter mirror. With that rig, we were able to get as wide as 4.5mm [the equivalent of15mm in 35mm], which I believe is unprecedented in 3-D. The oversized mirror wasn’t really conducive to handheld work, so we kept it on a Technocrane most of the time.”

Avatar is set roughly 125 years in the future. The story follows former U.S. Marine Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), a paraplegic who is recruited to participate in the Avatar Program on the distant planet Pandora, where researchers have discovered a mineral, Unobtainium, that could help solve Earth’s energy crisis. Because Pandora’s atmosphere is lethal for humans, scientists have devised a way to link the consciousness of human “drivers” to remotely controlled biological bodies that combine human DNA with that of Pandora’s native race, the Na’vi. Once linked to these “avatars,” humans can completely control the alien bodies and function in the planet’s toxic atmosphere. Sully’s mission is to infiltrate the Na’vi, who have become an obstacle to the Unobtainium-mining operation. After Sully arrives on Pandora, his life is saved by a Na’vi princess, Neytiri (Zoe Saldana), and his avatar is subsequently welcomed into her clan. As their relationship deepens, Sully develops a profound respect for the Na’vi, and he eventually leads a charge against his fellow soldiers in an epic battle.

For the film’s live-action work, Cameron teamed with Mauro Fiore, ASC, whose credits include The Kingdom, Tears of the Sun and The Island (AC Aug. ’05). “Jim saw The Island and Tears of the Sun, and he was apparently impressed with the way I’d treated the jungle and foliage scenes in both films,” says Fiore. “They brought me in for a three-hour interview, and [producer] Jon Landau walked me through the whole 3-D process, the motion-capture images, the promos and trailers they had done. The next day, I had a 30-minute interview with Jim, and we hit it off. They were already deep into production on the motion-capture stages in Playa del Rey, [Calif.,] and they were preparing to shoot the live-action footage in New Zealand.”

“The challenge for me, and what really got me excited about the film, was to use the tools to tell the story in the best way possible. It required a lot of experimentation and a reinterpretation of how I deal with composition and lighting.”

— Mauro Fiore, ASC

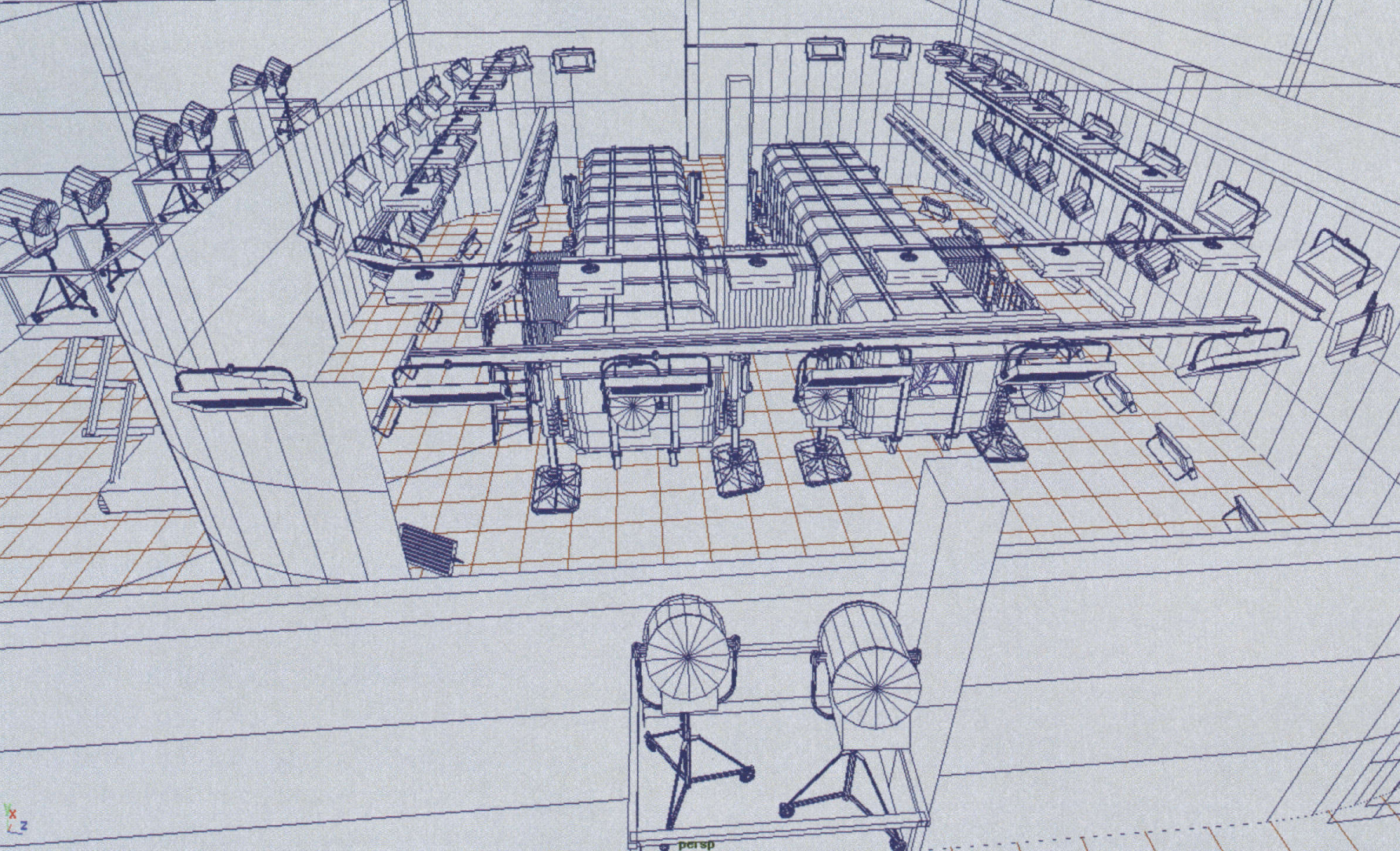

The technology employed on Avatar enabled Cameron to design the film’s 3-D computer-generated environments (created by Lightstorm’s in-house design team) straight from his imagination. By the time Fiore joined the show, the director had been working for 18 months on motion-capture stages, shooting performances with actors who would be transformed into entirely CG characters. Glenn Derry, Avatar's virtual-production supervisor, contributed a number of innovations A virtual diagram shows a pair of "remote research stations" that were built in a former Mitsubishi factory in New Zealand.

stations" that were built in a former Mitsubishi factory in New Zealand.

Gaffer Chris Culliton explains, "Because we had these exact virtual models of the warehouse and the sets, we were able to design and test the lighting and greenscreen weeks before we arrived in Wellington. As you can see, on the real set we decided to go with 24-light Dino softboxes rather than 20Ks on the rolling truss; the ability to change the bulbs and the diffusion allowed us more options for a soft, ambient push. Between the Dinos, we also hung 10K beam projectors to create a hard, warm sun feeling where needed." that helped Cameron achieve what he wanted. With all of the locations prebuilt in Autodesk MotionBuilder and all of the CG characters constructed, Derry devised a system that would composite the motion-capture information into the CG world in real-time. He explains, “With motion-capture work, the director usually completes elaborate previs shots and sequences, shoots the actors on the motion-capture stage, and then sends the footage off to post. Then, visual-effects artists composite the CG characters into the motion-capture information, execute virtual camera moves and send the footage back to the director. But that approach just wasn’t going to work for Jim. He wanted to be able to interact in real-time with the CG characters on the set, as though they were living beings. He wanted to be able to handhold the camera in his style and get real coverage in this CG world.

“Jim used two main tools to realize his virtual cinematography,” continues Derry. “One was a handheld ‘virtual camera,’ which was essentially a monitor with video-game-style controls on it whose position was tracked in space. Using the virtual camera during the mocap portion of the shoot, Jim could see the actors who were wearing mo-cap suits as the characters they were playing. For example, by looking through the virtual camera, he’d see Neytiri, the 9-foot-tall Navi, instead of Zoe Saldana. He’d operate the virtual camera like a regular camera, with the added benefit of being able to scale his moves to lay down virtual dolly tracks and so on. For instance, if he wanted to do a crane shot, he’d say, ‘Make me 20-to-1,’ and when he held the camera 5 feet off the floor, that would be a 100-foot-high crane.

“The other tool was the SimulCam, a live-action camera with position reflectors that could be read by mo-cap cameras,” continues Derry. “It superimposed the CG world and characters into the live-action photography by tracking the position of the live-action camera and creating a virtual camera in the CG world in the same place. The two images were composited together live and sent to the monitors on the set [as a low-resolution image].” For example, when Cameron was shooting a scene in a set involving an actor and a CG Na’vi, if he tilted the camera down to the actor’s feet, the viewfinder would show not only the actor’s feet, but also the Navi’s feet, the entire CG environment and the CG details outside the set, such as action visible through windows. All of this could be seen in real-time through the SimulCam’s viewfinder and on live monitors on the set, allowing the human actors to interact directly with the CG characters and enabling Cameron to frame up exactly what he wanted.

“With the SimulCam, you don’t have to imagine what will be composited later — you’re actually seeing all of the pre-recorded CG background animation,” says Derry. “So if you want to start the shot by following a ship landing in the background and then settle on your actor in the frame, you can do that in real-time, as if it’s all happening in front of you. On every take, the CG elements are going to replay exactly as they’ve been designed, and you can shoot however you want within that world.”

Because the SimulCam becomes a virtual camera in a virtual world, it can be placed anywhere in space. Standing more than 9' tall, the Na’vi are larger than humans by a ratio of 1.67:1. If Cameron wanted a shot to be at the Navi’s eye level, he would ask the system operator to make him 1.67:1, which would reset Cameron’s height to that level. In other words, he could continue to handhold the camera on the real stage floor while “standing” at a height of 9' in the virtual world. “Jim used the SimulCam as a kind of virtual viewfinder to direct the performances and get the shots he wanted, and then, in post, we’d tweak things further,” says Derry. “We could redo the art direction of the set by moving a tree, moving a mountain, or adjusting the position of a ship or the background players. For Jim, it's all about the frame; what's in the frame tells the story.”

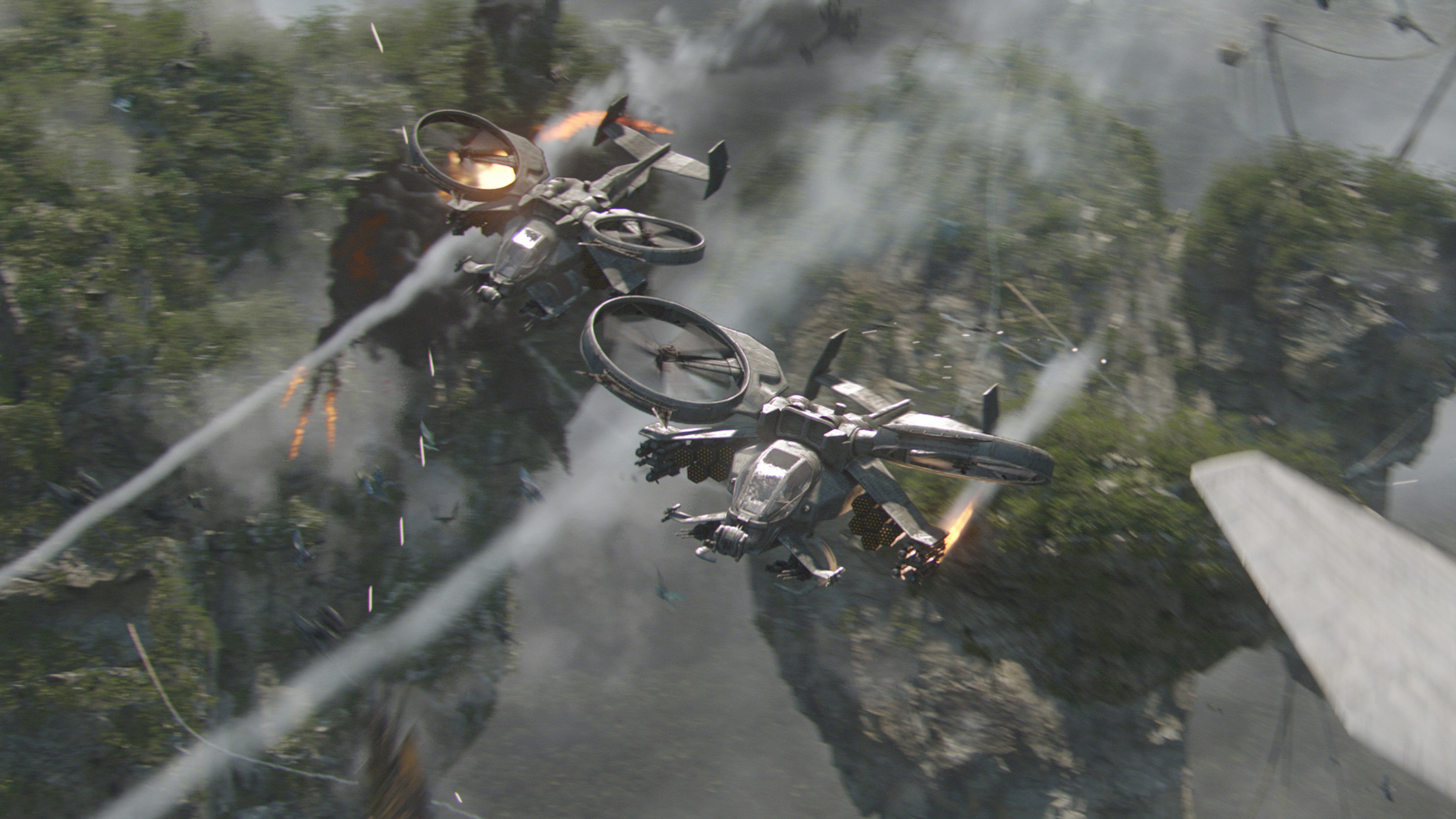

Virtual camera operator Anthony Arendt, who also operated the Fusion cameras alongside Cameron in the L.A. unit, recalls, “After Jim was happy with his takes from the SimulCam, they were still far from ready to send to Weta. We screened every shot in 3-D with him in Military helicopters fire their missiles into Pandora's toxic atmosphere. The "staggered teasers" strategy was also employed for these greenscreen shots. a theater nicknamed ‘Wheels and Stereo,’ and he gave us meticulous notes on every aspect of the shots. Fie gave the virtual artist notes on the overall scene and all of its detail; he gave stereographer Chuck Comiski notes on the 3-D, and he gave me specific notes on the camera moves. Because the recorded motion-capture images lack depth-of-field, he also gave me detailed notes on depth-of-field cues that would help Weta down the line. We treated depth-of-field as if we were shooting with one of the 3-D Fusion cameras.

“As the project progressed, we figured out ways to give Jim’s SimulCam shots the specific feel of different moves: Steadicam, Technocrane, handheld and so on. We could do that a number of different ways, depending on how the shot started and what Jim wanted to end up with. In the theater, we’d play back Jim’s SimulCam shots through MotionBuilder and then re-operate the shots according to his notes. He was very specific. For example, he gave me a note that said he wanted a shot from one of the Scorpion gunships to feel like it was shot from a Tyler mount, not a Spacecam. His attention to detail was mindblowing!”

After 18 months of motion capture, Cameron brought in Fiore to shoot live-action footage onstage at Stone Street Studios in Wellington, New Zealand. “About 70 percent of the movie is motion capture, and the rest is live-action,” says Fiore. “Although the motion-capture work was mostly finished, the actual look of the film was yet to be created. The footage we shot in New Zealand ultimately defined the overall style of the movie.”

Because all of the sets were created in MotionBuilder long before any physical construction began, Fiore was able to take a virtual tour of the sets and plan his approach. “We spent a good month in Los Angeles laying out the lighting plan in the virtual sets,” the cinematographer recalls. “We were able to position specific fixtures and see exactly what it would do in the environment. We had accurate measurements of the real stages, so we knew where we had to work around low ceilings or support beams, for example, and we could solve those problems well before we ever set foot on the stages in New Zealand. We also spent a great deal of time blocking scenes on the virtual sets. Basically, all of our tech scouts were done virtually.”

This process revealed a problem that Fiore and his gaffer, Chris Culliton, would confront in the Armor Bay set. A massive armory on Pandora, this set piece would stand 100' tall and hold hundreds of Armored Mobility Platform suits, large, robot-like devices that the soldiers can control. In reality, the set was constructed in a former Mitsubishi factory in New Zealand, and only two AMP suits were made, one functional and one purely for set dressing. The ceilings in the factory were just 22' high, so the rest ofthe set had to be created digitally.

“The challenge was that a lot of the shots in the Armor Bay were looking up at this great expanse of a 100'-tall location that simply didn’t exist — we were looking up into our lighting fixtures and the ceiling,” says Culliton. “We had to find a way to light from above yet still have a greenscreen up there so the rest of the set could be added later.”

To solve the problem, Culliton and key grip Richard Mall took a cue from the theater world and hung greenscreen teasers of different lengths from the ceiling. The teasers were hung in between the rigging; the lights were clear to illuminate the set, but from the camera position, the teasers hid the fixtures. “We hung the teasers perpendicular to the ceiling, covering roughly 150 feet of ceiling space, with about 6 to 10 feet of space between each teaser,” says Culliton. “If you stood in the corner and looked up, it appeared as a single piece of greenscreen. On the camera side, between the teasers, we hung Kino Flos to light the green; we’d normally use green-spike tubes for greenscreen, but because of the lights’ proximity to the actors and the set, we went with standard tungsten tubes. To light the set, we hung 10Ks gelled with V2 CTB, and we had about fifty 10-degree Source Four Lekos gelled with V4 CTB and V4 Hampshire Frost hanging between the teasers. Those gave us little hits and highlights throughout the set.”

Greenscreen, in abundant supply on the shoot, was often placed close to actors and set pieces for particular composite effects, which led to concerns about green spill. Fortunately, while touring the Weta Digital facility, Fiore found a solution with the help of fellow ASC member Alex Funke. “We went over to visit with Alex, who shoots the miniatures for all of Weta’s work, and he showed us this 3M Scotchlite material, the same highly reflective material that’s used in traffic signs and safety clothing. He put it around the miniatures and lit them with ultraviolet light, which allowed him to pull really clean mattes without corrupting the rest of the set.”

Using standard black-light fixtures, Fiore and his team began attaching the Scotchlite material to specific aspects of a set or environment that would need to be replaced in post. Nearby, they would hide a small UV black-light fixture, which would retroreflect the bright green from the Scotchlite back to the camera without affecting the area around it. “In some situations, we also used green UV paint on various surfaces to achieve the same results,” notes Fiore. “These areas were small enough that we could light them with small sources. A 12-inch or 24- inch black-light tube was really all we needed.”

The UV technology was also applied to the avatar booths, tight, coffin-like enclosures that resemble MRI equipment. After a soldier lies down on a table, he is inserted into the booth, where his consciousness is projected into the body of his alien avatar. Circling around the opening of these machines is a spinning display of colored liquid (a CG effect). Because the CG area was very close to the actors and other set components, Fiore used the UV paint on the rim of the machine to prevent spill and create a clean matte for the CG work.

At the onset of principal photography in New Zealand, a dailies trailer incorporating two NEC NC800C digital projectors was set up so the filmmakers could view each shot in 3-D as it was completed. Playing back the recorded footage via a synchronized feed from a Codex digital recorder, Cameron and Fiore could experience the 3-D effects on location and refine them as needed, shot-by-shot. “We called it ‘the pod,’” Fiore recalls. “In the beginning, we were checking on nearly every shot to make sure the lighting was solid and the convergence and interocular were correct. It was a very laborious way to start working, but it was necessary. The cameras themselves were a bit finicky in the beginning, and sometimes getting them to match up was a challenge. If one was even slightly off in terms of focus, the whole effect was mined.”

Avatar was Fiore’s first digital feature — he had shot a commercial on HD — and his first foray into 3-D. “One of the things that was really tricky for me was the ⅔-inch-chip 3-D cameras’ extended depth-of-field,” he says. “It’s a lot like the depth-of-field you get with 16mm. It’s really difficult to throw things out of focus and help guide the audience’s eye. Shallow depth-of-field is an interesting dilemma in 3-D, because you need to see the depth to lend objects a dimensionality, but if you have too much depth-of-field and too much detail in the background, your eye wanders all over the screen, and you’re not sure what to look at. I had to find new ways to direct the audience’s eye to the right part of the frame, and we accomplished that through lighting and set dressing. We strove to minimize the distractions in the background. I learned that if I controlled the degree of light fall-off in the background, I could help focus the viewer’s attention where we wanted it. Instead of working with circles-of-confusion, I had to create depth-of-field through contrast and lighting levels, which was a really fun challenge.

“Once we started shooting, we quickly discovered that highlights in the background were a problem because depending on the convergence of the scene, two distinct images of that highlight might diverge, creating a ghosting effect that was very distracting,” continues Fiore. “Even a practical fluorescent could cause a problem. I tried a few experiments, like putting polarizing gel on the highlight sources and a Pola on the lens and then trying to dial them out, but as soon as the camera moved, the effect was gone. So I had to bring in smoke, where I could, to bring down the contrast.”

Fiore also had to rethink his approach to composition. “Anytime you’re in a position where one lens is obstructed by an object and the other isn’t — say, when you’re shooting over someone’s shoulder or through a doorway — you get into a situation your eyes can’t comfortably handle in 3-D. Whenever we got into that type of situation, we had to be very careful to ensure both lenses were seeing both the obstruction and the clear view.”

Because so much of the film’s world is virtual, Fiore was constantly matching interactive lighting with elements that would be comped into the image in post. An example of this is a plasma storm that takes place on Pandora. “What is a plasma storm? No one knows — it’s all inside Jim’s head!” Fiore exclaims with a laugh. “We had to figure out a way to create a fantastic event that no one had ever seen before.”

In the scene, Sully is in a remote science lab with Dr. Augustine [Sigourney Weaver], and they see the storm happening outside the windows. We had to find a way to create the effect of the storm on their faces.” He turned to the DL.2, a DMX-controlled LCD projector that acts like an automated light source. By utilizing a preset “anomalous” pattern in the DL.2 and projecting the image through Hampshire Frost onto the actors faces, Fiore achieved a unique look for the storm’s lighting effects.

Interactive lighting was also crucial for selling process shots inside vehicles, such as the military helicopters that swarm around Pandora. “The helicopters were built on a gimbal system,” says Culliton. “The gimbals were strong and capable of some good movement, but they only created about 15 degrees of pitch and roll. Jim’s paramount concern is realism, and helicopters move a lot more than 15 degrees, especially on military maneuvers. When they turn, they turn very quickly. We had to find a way to represent that speed and velocity through light.”

Fiore explains, “We put a 4K HMI Par on the end of a 50-foot Technocrane arm and used the arm’s ability to telescope and sweep around to get the feeling of movement in the helicopters. When the helicopter turned, that sunlight would move through the cockpit, throwing shadows from the mullions onto the faces of the actors. By exploiting the Technocrane’s arm, we could quickly zip the light from one end to the other and create the impression of fast movement.”

Because the light was positioned on a remote head controlled by standard camera wheels, Fiore asked his camera operators to control the light. To assist the operator, a small lipstick camera was mounted to the Par and fed back to the operator’s monitor, allowing him to operate the lamp just like a camera; he could aim the beam precisely where Fiore wanted it to hit the helicopters.

For the climactic sequence, in which a human army descends on Pandora to attack the Na'vi, the stages at Wellington weren’t large enough to hold the construction crane required to drop a mock helicopter full of soldiers. Instead, the production moved outside to the parking lot, setting the scene against a 400'-wide-by-50'-high curved greenscreen (built out of industrial shipping containers faced with plywood and painted chroma green).

The sequence takes place during the day, but Cameron insisted it be shot night-for-day. “At first I thought he was insane,” recalls Fiore. “But when I thought about it, I realized it made a lot of sense. We had to be able to completely control the light without worrying about sun direction or cloud coverage. As crazy as it might seem to shoot an outdoor day scene at night, it was the right decision.”

Two 100-ton construction cranes were positioned to hold a lighting truss over the outdoor set. (A third crane supported the helicopter.) “We built a 60-by-40-foot truss structure complete with grid and walkways,” says Culliton. “We basically turned the outdoors into a working greenbed! Above the truss, we suspended a 100K SoftSun through a large frame of light Grid and XA Blue, mimicking the ambiance of the Pandoran sky. We also hung a combination of 7K and 4K Xenons and 4K HMI beam projectors to get shafts of daylight through the vegetation, which was added later.”

“This entire production was extraordinary, the most extraordinary experience of my career so far,” says Fiore. “The challenge for me, and what really got me excited about the film, was to use the tools to tell the story in the best way possible. It required a lot of experimentation and a reinterpretation of how I deal with composition and lighting. There were times when it was a miserable experience, but I know that everything from here on out is going to be a lot easier! If you’re going to delve into new technology and a new world, Jim Cameron is the guy to do it with.”

1.78:1

High-Definition Video

Sony F950, HDC1500, F23; SimulCam

Fujinon zoom lenses: HA16x6.3BE, HA5x7B-W50

Digital Intermediate

Fiore earned an Academy Award for his outstanding contributions to this record-setting film, which will be re-released in the U.S. on September 23 — remastered in 4K HDR.

AC will cover the production of the sequel Avatar: The Way of Water — photographed by Russell Carpenter, ASC — in an upcoming issue. The film will be released on December 16.