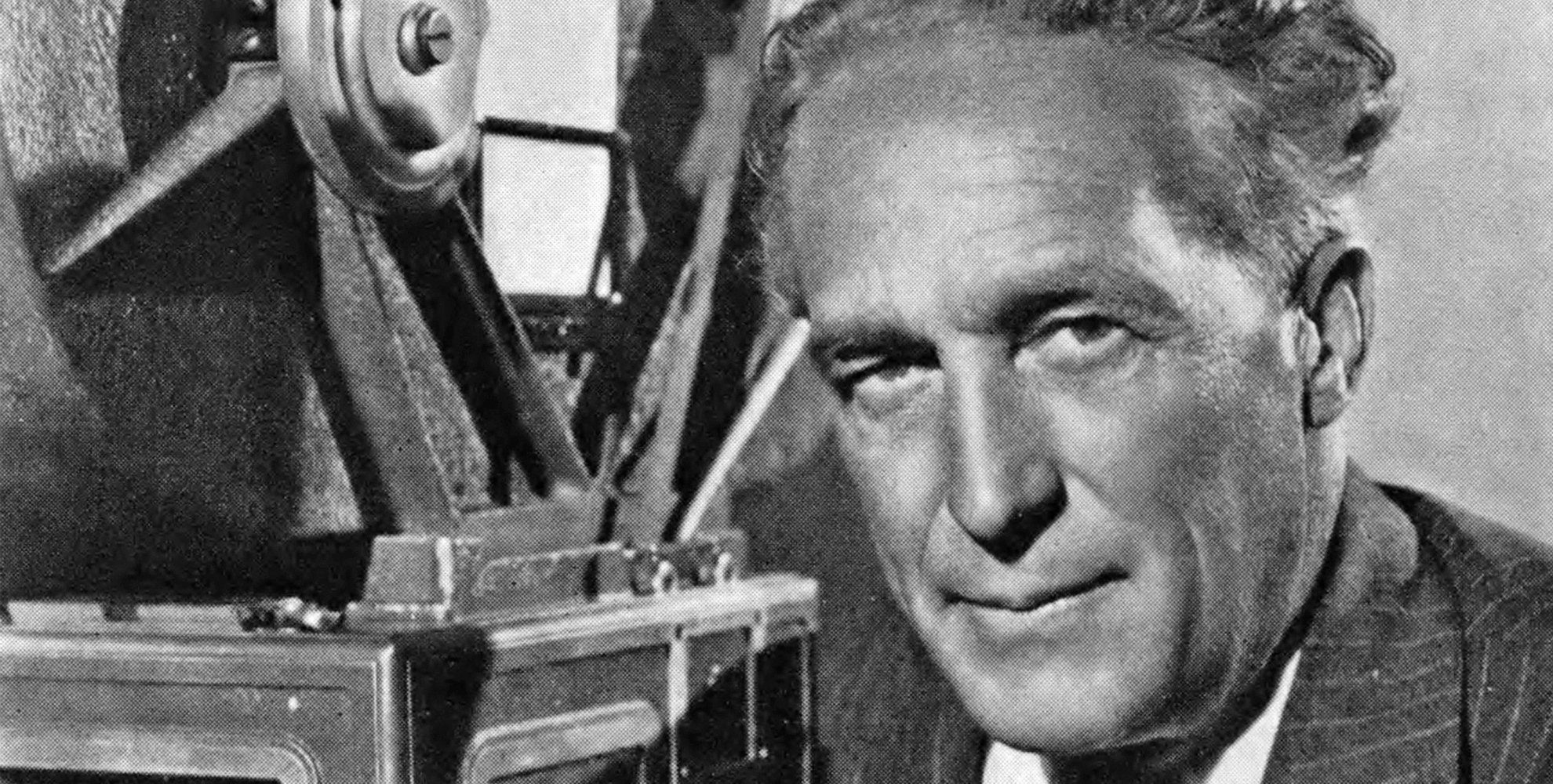

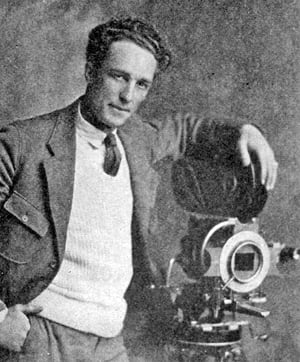

Aces of the Camera: Ernest Palmer, ASC

“There’s something so much more satisfying — more complete — about a scene photographed in color than there is about the same scene photographed in cold black-and-white.”

“Aces of the Camera” was a profile series that ran in AC for several years starting in the early 1940s. This article was originally published in AC, Nov. 1941.

One of the real pleasures of visiting the 20th Century-Fox studio is the privilege of dropping in for a chat with Ernest Palmer, ASC, on the set. For Ernie Palmer has a very special way of greeting his on-the-set visitors; with no sense of affectation at all, he somehow manages to convey the impression that he is genuinely glad to see you — that your visit is in itself one of the pleasanter highlights of his day. No matter how busy he may be, or how important the action he is photographing, he finds time always to greet you with warm friendliness, and to see to it that you have a comfortable chair before turning back, if he must, to the business of putting the next scene superbly on the screen.

And he is busy. For many years one of the studio’s top-ranking aces of black-and-white camerawork, today he has added to this accomplishment equal ranking as a camera-artist in color. He has probably been associated in the making of more Technicolor features than any other of the industry’s “production” cinematographers. Among them have been such films as Kentucky, Hollywood Cavalcade, Chad Hanna, Belle Starr and Blood and Sand. Most recently, with the currently released Weekend in Havana and his present production, Song of the Islands, Palmer has become one of the first “production” cinematographers to solo-pilot a major-studio Technicolor production.

Palmer very obviously likes color. If you ask him why, he’ll give you that deceptive slow smile of his, and confess, “I like to look at the rushes! There’s something so much more satisfying — more complete — about a scene photographed in color than there is about the same scene photographed in cold black-and-white. And color is infinitely flattering, not only to the players but to the cinematographer as well, so that it is really fun, rather than an ordeal, to go into the projection-room to screen your rushes if they are in Technicolor.

“It is always a surprising thing to me to see how many stars who have not previously appeared in a Technicolor picture seem somehow to rather dread the ordeal of facing the color camera, as if it were something that would mercilessly show up their unphotogenic points. Really, the exact opposite is true: Technicolor is the most completely flattering medium by which any star can be presented. The simple fact of the addition of color seems to do as much to enhance a player’s appearance as the whole bag of monochrome camera-tricks. We had a clinching proof of this in two recent releases of our studio — That Night in Rio, in Technicolor, and Great American Broadcast in black-and-white. Both of them were photographed by my friend Leon Shamroy, ASC, and Alice Faye appeared in both productions. Viewed strictly as examples of photography, there could be little choice between the two productions; both were photographed by the same artist, and both were good. But there was no comparison between the way Miss Faye appeared on the screen in the two films. It is well known that during the last year she has not been in the best of health: well, in the black-and-white production she sometimes showed it, while in the color film she did not. The same thing has happened with other stars, in other studios, too, so we may conclude very definitely that the best prescription for any player who may feel that overwork or time are taking their toll would be to insist on being photographed by the flattering color-camera.

“I’m sure by now the old idea that color-photography is harder and slower than black-and-white has been pretty well exploded.”

“The same thing works equally for the cinematographer, of course, for if in Technicolor he can make a player look better than she does in black-and-white, it is definitely to his advantage. Besides, it is, if anything, easier.

“I’m sure by now the old idea that color-photography is harder and slower than black-and-white has been pretty well exploded. I know that here at 20th Century-Fox, while of course they make some allowance for the added cost of lighting equipment, electrical crew and laboratory-changes, they make no other concessions to the traditional ‘difficulty’ of Technicolor. They give us exactly the same shooting-schedule as if we were working in black-and-white. We manage to adhere to those schedules, and sometimes even improve on them!

“As far as my own work goes, I find there’s a definite advantage to utilizing substantially normal black-and-white lighting techniques in color. In some instances, the fact of color and color-contrast helps us get pictorial effects and separation of planes without going to some of the trouble we’d go to in getting comparable effects in monochrome. But in general, good lighting is good lighting, whether you do it in black-and-white or in color.

“The chief difference is in the color and intensity of the lighting. Naturally for Technicolor you must use light conforming to the daylight-white standard if you want normal results, though nowadays you can make almost equal use of arcs or inkies as occasion may demand. And you still have to light Technicolor at a rather higher level than black-and-white.

“But there’s no longer any such thing as getting ‘typed’ on color. In between my Technicolor assignments, I’ve made several black-and-white pictures; my next after Song of the Islands will probably be in black-and-white, too. And neither the studio executives nor I have found any reason for thinking my work in color has hurt my ability to photograph good black-and-white. As a matter of fact, just before I took on this Technicolor assignment, I filled in several days on added scenes on a black-and-white picture. And I found that, due to the system of using light-meters inaugurated here by Supervisor of Photography Dan Clark, ASC, about the only change that was necessary was to reduce the intensity of my lighting. That, using the meter, was of course easy. And I found that with that change, I could carry on equally well regardless of whether I was using color or monochrome.

“And here’s something: One of these days, when I get a bit more time between studio assignments, do you know what I think I’ll do for a hobby? I’m going to get myself a 16mm camera — and shoot home movies in Kodachrome!

Palmer passed away in 1978 at the age of 92. Before his retirement in 1957, he accumulated four Oscar nominations for Best Cinematography, including a win in 1942 for Blood and Sand, which he shared with fellow ASC member Ray Rennahan. Palmer finished his career with 143 credits to his name, spanning five decades in the industry.