Aces of the Camera: Leon Shamroy, ASC

“Styles in cinematography change just as much as styles in clothes or anything else. They tend to move in cycles.”

“Aces of the Camera” was a profile series that ran in AC for several years starting in the early 1940s. This article was originally published in AC, May 1941.

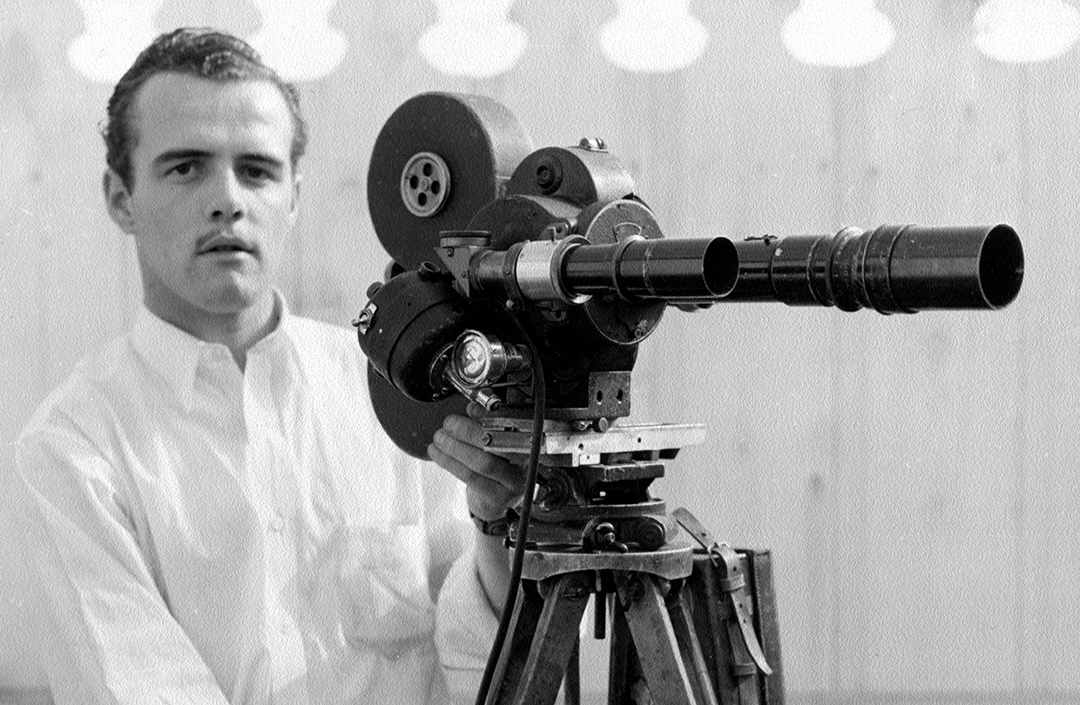

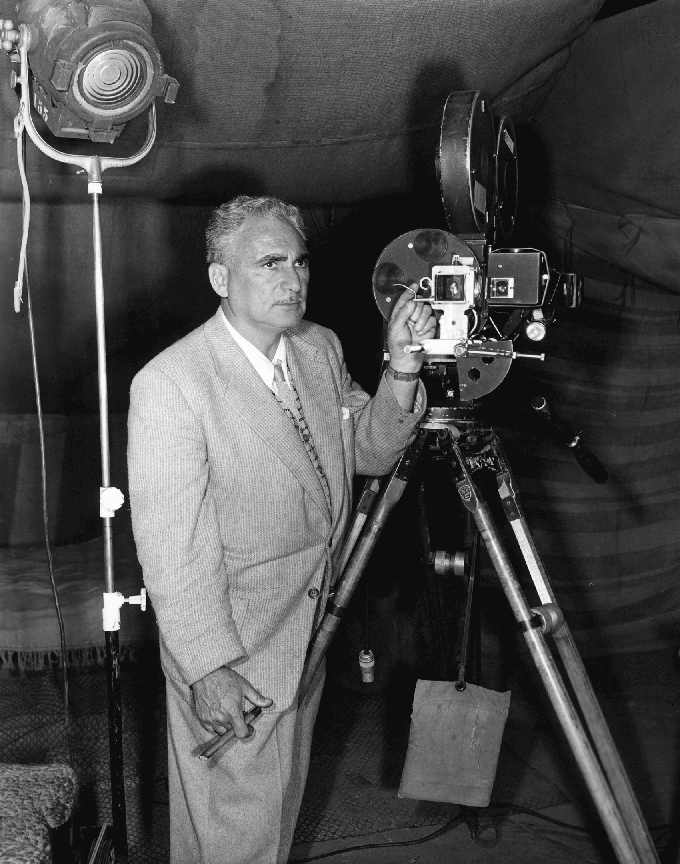

Director of photography Leon Shamroy, ASC is an engineer turned artist. More years ago than he cares to be reminded of, a vacation job in one of the early studios changed him permanently from an engineering student to an aspiring camera assistant. Turning to the camera with enthusiasm and with the true engineer’s instinct for precision he began the climb which has since made him one of the industry’s outstanding masters of the camera.

Despite his change of professions, the engineer’s viewpoint still remains, for he combines the sensitive feeling of the artist with the accuracy of the bridge-builder he might have been. Regardless of subject matter, or whether the picture is in monochrome or color, Shamroy’s photography is above all characterized by an underlying technical precision and brilliance which bespeak the methodical mind of the engineer.

To him, there can be but one right approach to any scene — but one really correct photographic treatment. Each technical trick in the cinematographer’s repertoire is valuable only as the man at the camera knows how to use it in its precisely right place.

“We’re fond of saying that cinematography is both an art and a science,” Shamroy points out. “It is. But in some ways, the two aren’t so very different, for in either art or science a workmanlike performance means having each element in its exactly right use and place. A good engineer wouldn’t put a bridge-girder into an airplane wing just because it happened to be handy; in the same way, an artist, whether he uses a brush or a camera, wouldn’t put a highlight here and a shadow there just because he felt like it: he’d put them there because they belonged in that relation and couldn’t go any other way.

“That’s the way I try to approach cinematography. I think most of us nowadays realize the importance of this kind of accuracy about details of lighting, composition, camera movement, and so on. But it is even more true of other photo-technical details. Take the new coated lenses, for instance. Technically, they’re a tremendous improvement. They give added speed together with a brilliance, snap, increased depth and shadow-detail which are, generally speaking, very desirable characteristics.

“But there are times, too, when these qualities would be badly out of place in a picture. It’s easy to imagine some types of dramatic scenes where, in order to stress the mood of somber drama or mystery, you might find it best to go deliberately out of your way to avoid the literalness of a coated lens’ image— perhaps using older, uncoated lenses, or accentuating the diffusion, as might be desirable to fit the mood of the particular scene in hand.

“There’s an added realism — and an added artistic and technical satisfaction — to color which simply can’t be approached in black-and-white.”

“Don’t forget, too, that styles in cinematography change just as much as styles in clothes or anything else. They tend to move in cycles, too. Right now we’re emerging from a period when diffusion and overall softness — optical and tonal — have been the accepted style, and crispness and extreme depth of field are coming into vogue.

“This is desirable alright. But to me, it is simply the turning of the cycle. It really wasn’t so many years ago that to be good cinematography everything in the scene had to be sharp. That was back in the days when our best lenses were f:3.5 Dagors and Tessars — critically sharp-cutting anastigmats — and film and laboratory-work tended to strong contrasts, too.

“This was over-done, and faster, softer lenses — many of them less perfectly corrected — came in. Softer, panchromatic emulsions came in; the softer Mazda light was developed to take the place of the old hard arc light. Film was processed to softer standards. And this, too, was over-done.

“So what are we doing today? We have fast lenses, and we’re stopping them down to apertures of f:3.5 and smaller, to gain depth and definition. We’re applying coatings that sharpen up the image by removing internal glare and reflections. Our laboratories are learning to put more snap and vigor into their processing. Cinematographers in almost every studio are making increased use of arcs in their lighting because the arc brings out textural details better in many instances than the Mazda. And it is all being hailed as new!

“Actually, it is going back to the ideas of years ago — but with the improvements we can gain from modern knowledge of lighting, filmmaking, and the like. It’s not new — but you can’t say it’s a backward step, either. To me it is just another phase in the search all of us are constantly making to find ways of making our pictures better and more dramatically real.

“I think the factor that will really bring us closest to this reality is color. Maybe not the color of today, but the color it is developing into. I have made several Technicolor pictures, and, frankly, I prefer working in color to black-and-white. There’s an added realism — and an added artistic and technical satisfaction — to color which simply can’t be approached in black-and-white. It is almost like a new dimension. That sounds as though I were a Technicolor press-agent, but it is a literal fact; I think any cinematographer who has ever made a modem color production will agree with me.

“And in this, I’m speaking not solely as a cinematographer, for color is coming to mean something at the box office, too. If it didn’t, you wouldn’t find a great showman like Darryl Zanuck (The Jazz Singer, The Public Enemy, The Grapes of Wrath) of 20th Century-Fox embarked on a constantly increasing program of Technicolor production. Maybe the public can’t analyze its reasons for liking color, but I’m confident it is because the color gives you at once greater realism and greater artistic possibilities. Just consider, for example, two recent productions in which Alice Faye appeared: That Night in Rio and The Great American Broadcast. I photographed both of them, so comparisons won’t hurt. One was in Technicolor, the other in black-and-white. But after seeing Alice Faye in the Technicolor picture, and then seeing her in the black-and-white one, most audiences, I think, feel instinctively that she was more real in the color picture. They don’t analyze it, but they feel instinctively there’s something missing in the black-and-white film.

“I don’t blame them. I did the black-and-white job soon after doing the Technicolor one — and every day as I looked at the rushes I was dissatisfied with the best we could do with Miss Faye in the black-and-white picture! In some instances, we were giving her technically better photography, I think — but because the element of color was missing, we all felt instinctively something was wrong.

“Perhaps the best indication of the way the public feels about this is the way amateur movie-makers have swung to color. They tell me that now about 90 percent of the films you’ll see in most amateur movie clubs are in Kodachrome. Well, I’m confident that as they get the economic end of color into closer parity with black-and-white, and the technical end simplified so you aren’t slowed down by the bulkier three-film cameras and so on, we professionals are going to folow that same lead. And when we do, we’re going to find ourselves doing better and more satisfying work than ever before!”

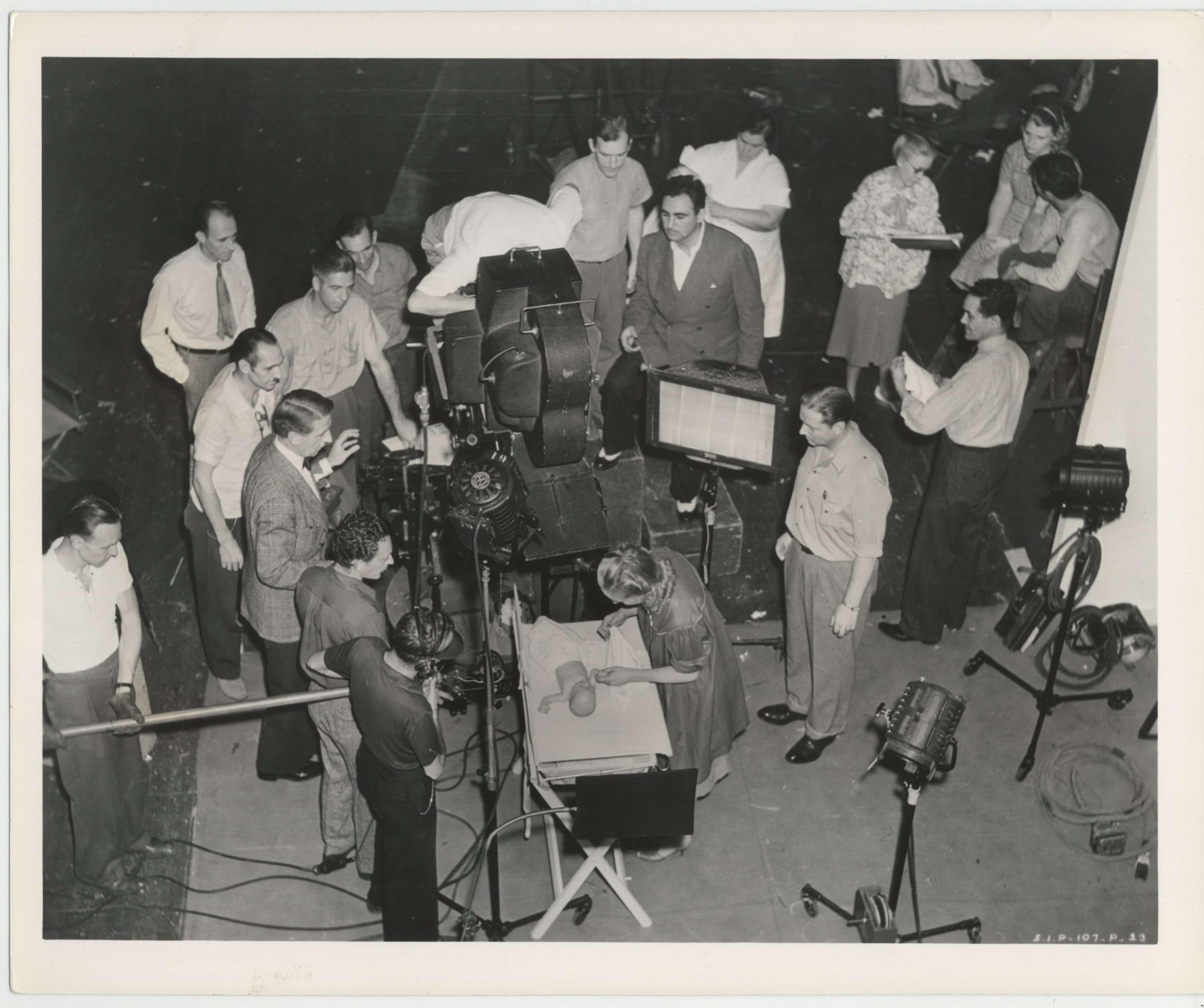

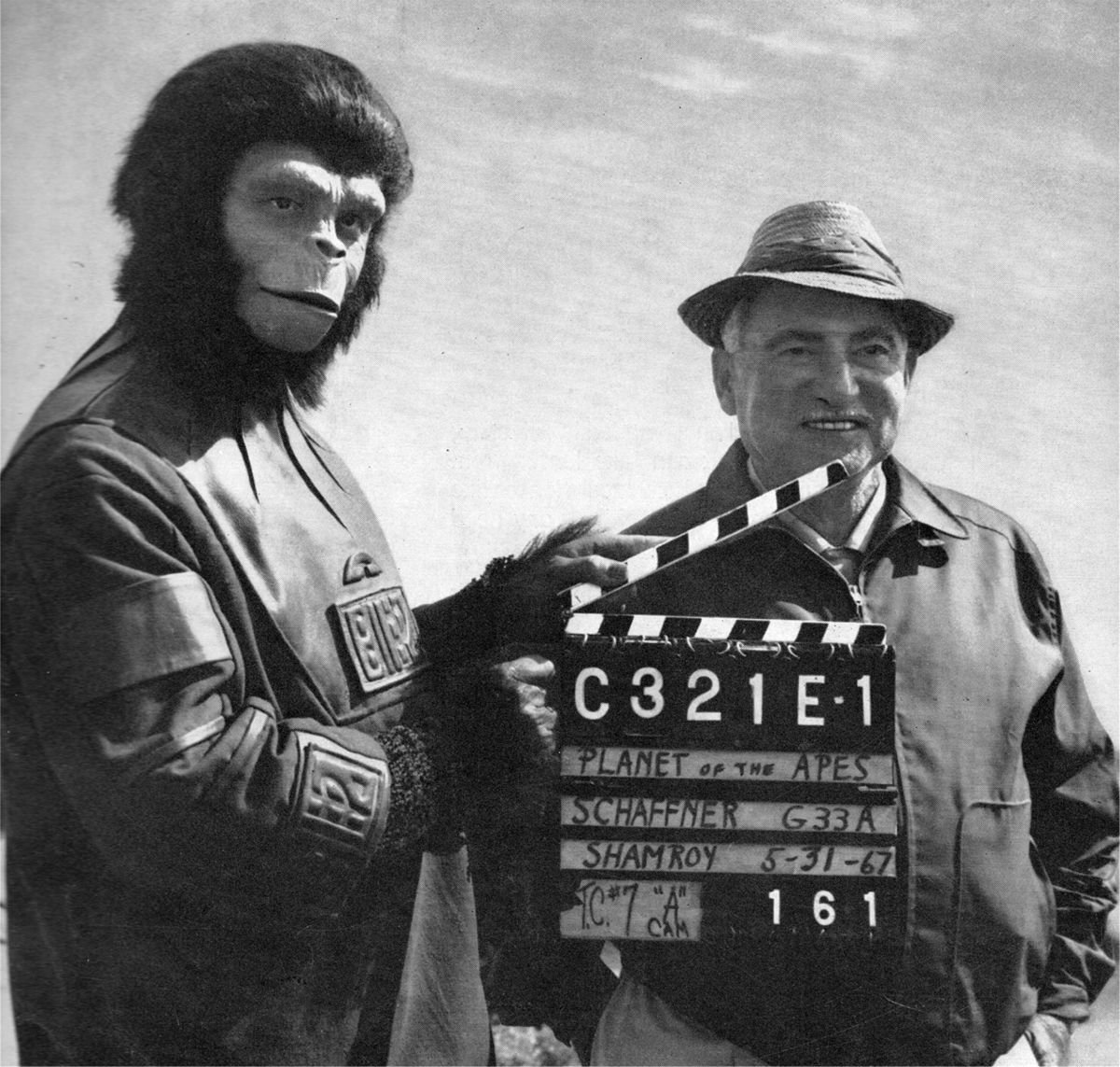

Shamroy went on to add to an already impressive resume with hits like A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Cheaper By The Dozen, The Robe, The King and I, South Pacific and Planet of the Apes.

He also served as ASC President, from 1947-’48.

He finished his career with a staggering 18 Best Cinematography nominations from the Academy (tied for the most ever with Charles Lang, ASC), including four Oscar wins; The Black Swan (1943), Wilson (1945), Leave Her to Heaven (1946) and Cleopatra (1964).

He penned this prescient essay — “The Future of Cinematography” — in AC Oct 1947, predicting today's age of "electronic" cinematography.

Shamroy passed in 1974 at the age of 72.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.