The Future of Cinematography

“Not too far off is the ‘electronic camera.’ A compact, lightweight box no larger than a Kodak Brownie, it will contain a highly sensitive pickup tube, 100 times faster than present-day film stocks.”

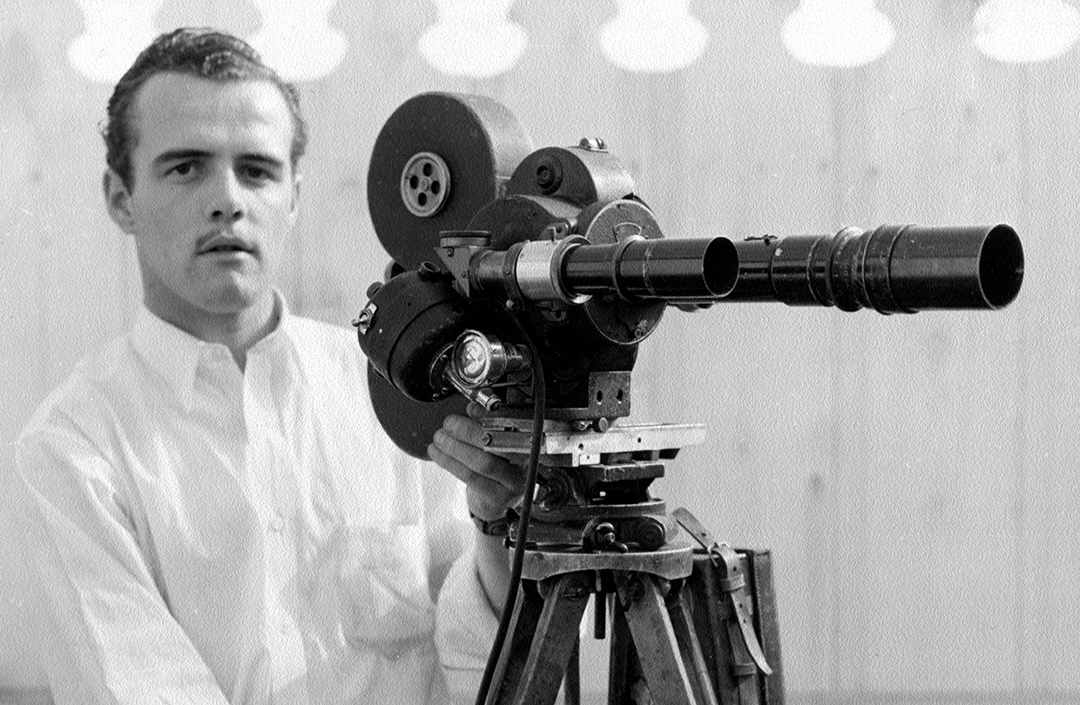

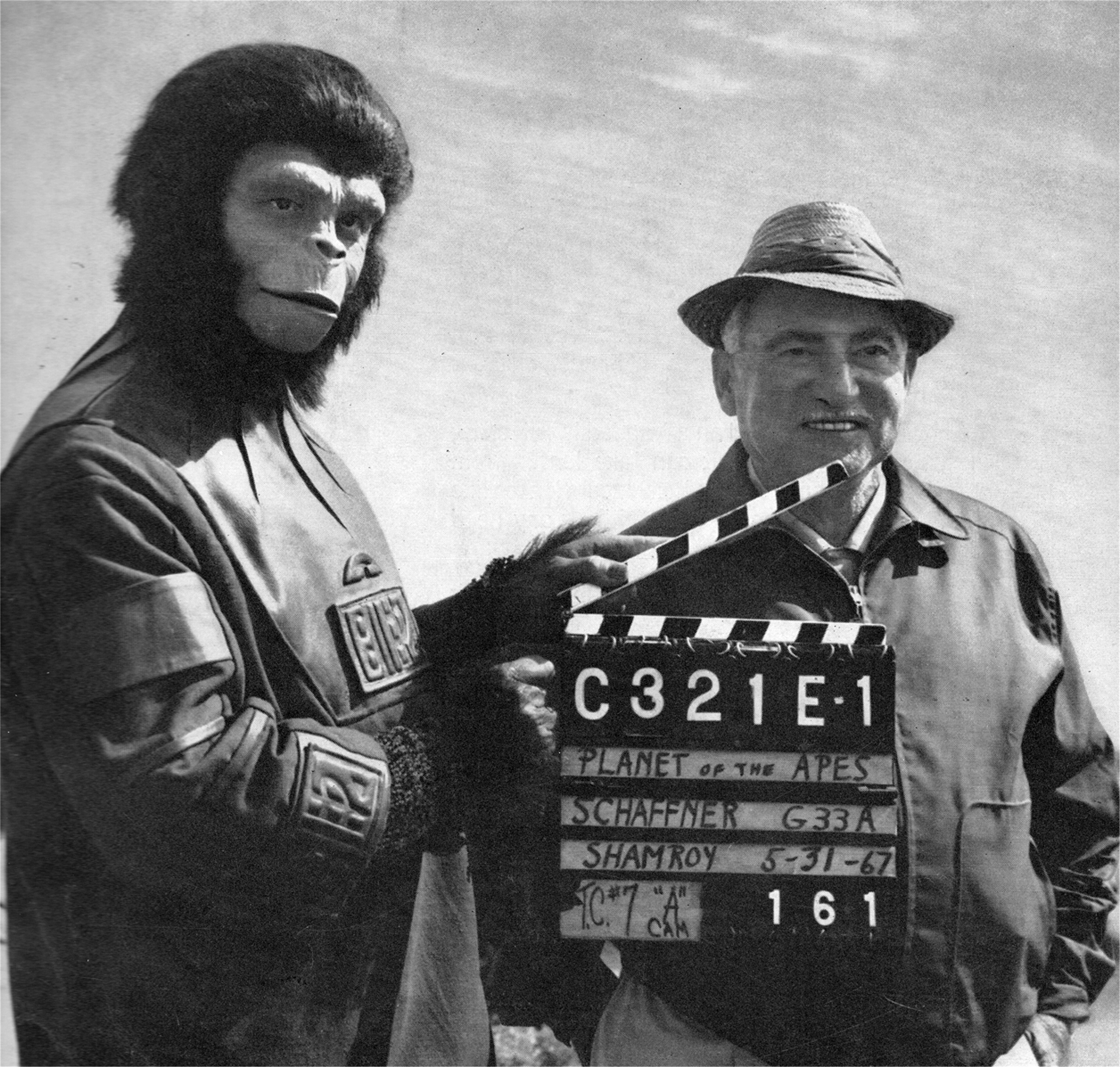

By Leon Shamroy, ASC

The motion picture industry has more than its share of skeptics and critics. Twenty years ago, when pictures were on the verge of talking, they protested, "We've gone as far as we can go."

Despite the loud wailings, impossible dreams have become technological practicalities. Pictures talk in vivid colors. New dimensions of realism have been added.

The critics had their innings. With the advent of sound, they proclaimed the art of the motion picture dead. Sound could never be accepted as a substitute for the pantomimist. But the so-called death of an art proved to be a rebirth.

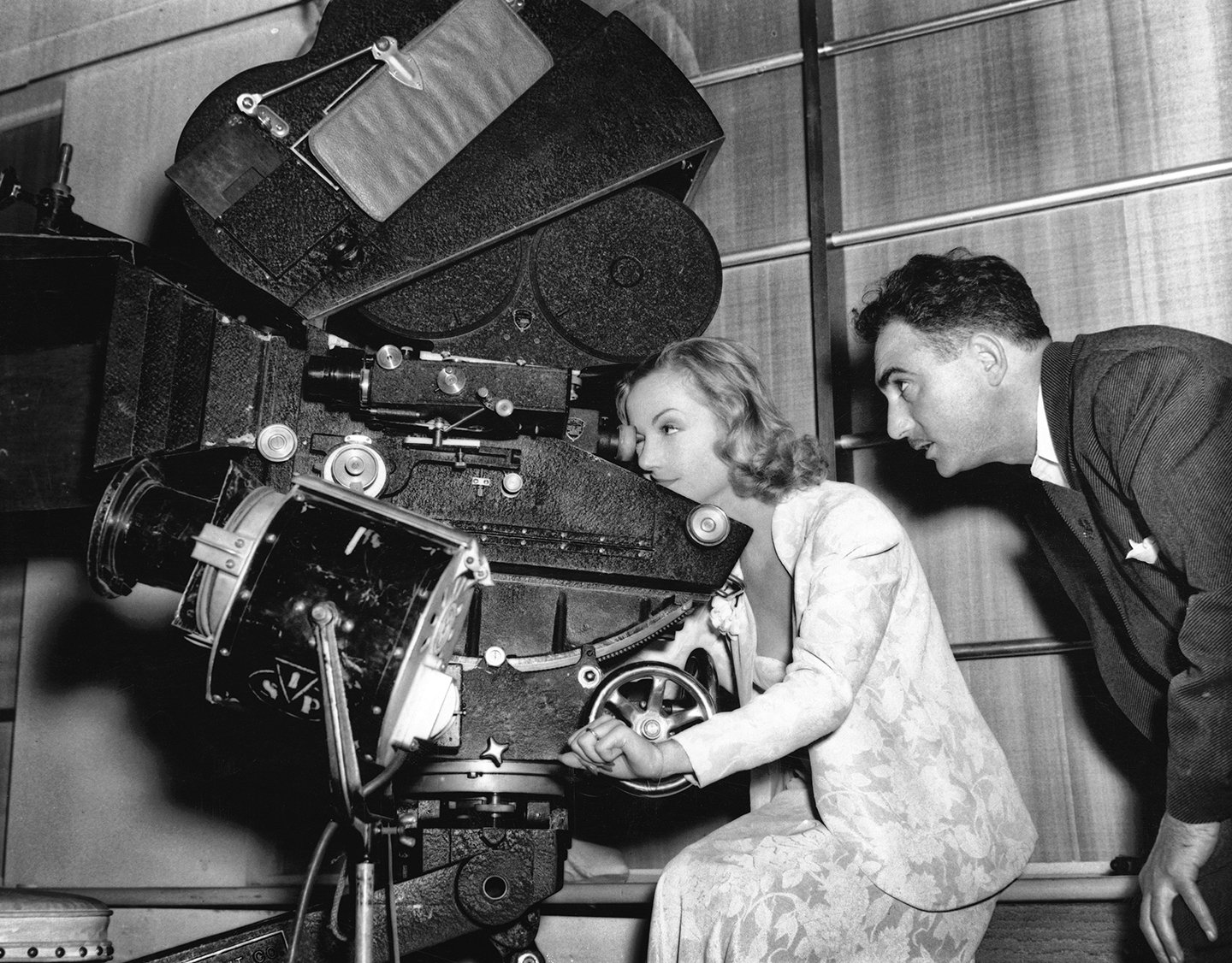

The stature of the motion picture as an art has grown, and with it the art of the cinematographer. For many years, the men behind the camera have sought to erase the popular misconception that they are something more than mechanics who point the camera and get the picture right every time.

A director of photography makes something more than a mere technical contribution to a motion picture. What the writer has created in the written word must be translated to the screen though the eyes and minds of the director and the cinematographer.

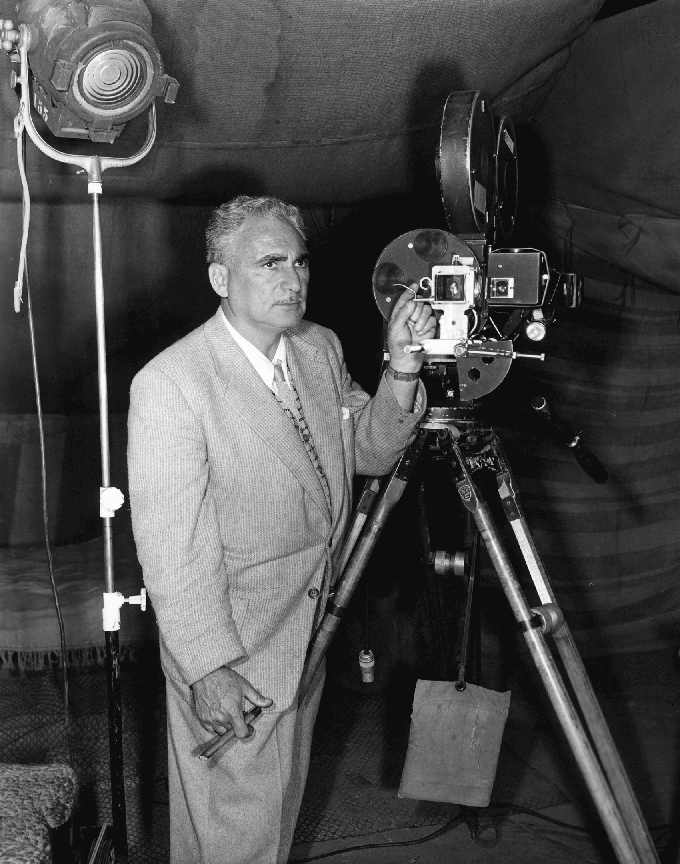

With the proper lighting, a mood can be established, an emotion emphasized, and realism heightened. The trend toward realism, however, has put many a cameraman in the position of a tightrope walker. While called upon to inject realism, he knows that to millions of filmgoers, the motion picture is a welcome escape from their everyday trials and tribulations. The basis of this escape is bound up in the illusion of the medium. To destroy this illusion with ultra-realism can mean jeopardizing large investments. The cinematographer frequently finds himself in the awkward and unhappy position of serving two masters. The critics then scream, "Art is being compromised!" But is it? While it's the direct responsibility of the cinematographer to guarantee the investment of the film industry, indirectly he feels a responsibility to those millions who look to the screen for that intangible something. Call it entertainment, escape from torturous reality, relief from domestic worry. Whatever the name put on this appeal, the illusion must be preserved. And so the people must be pleased. The cameramen must make their heroines as the audience prefers them — young and beautiful, complete with smooth silken complexions — and make the heroes youthful, handsome and virile.

Even though unfettered by economic restrictions imposed upon him by the public's tastes, the creative cinematographer continues to experiment. He looks for new ways of intensifying mood and projecting the emotions of the actor beyond the screen. The limitless palette of color points the way to new avenues of photographic expression.

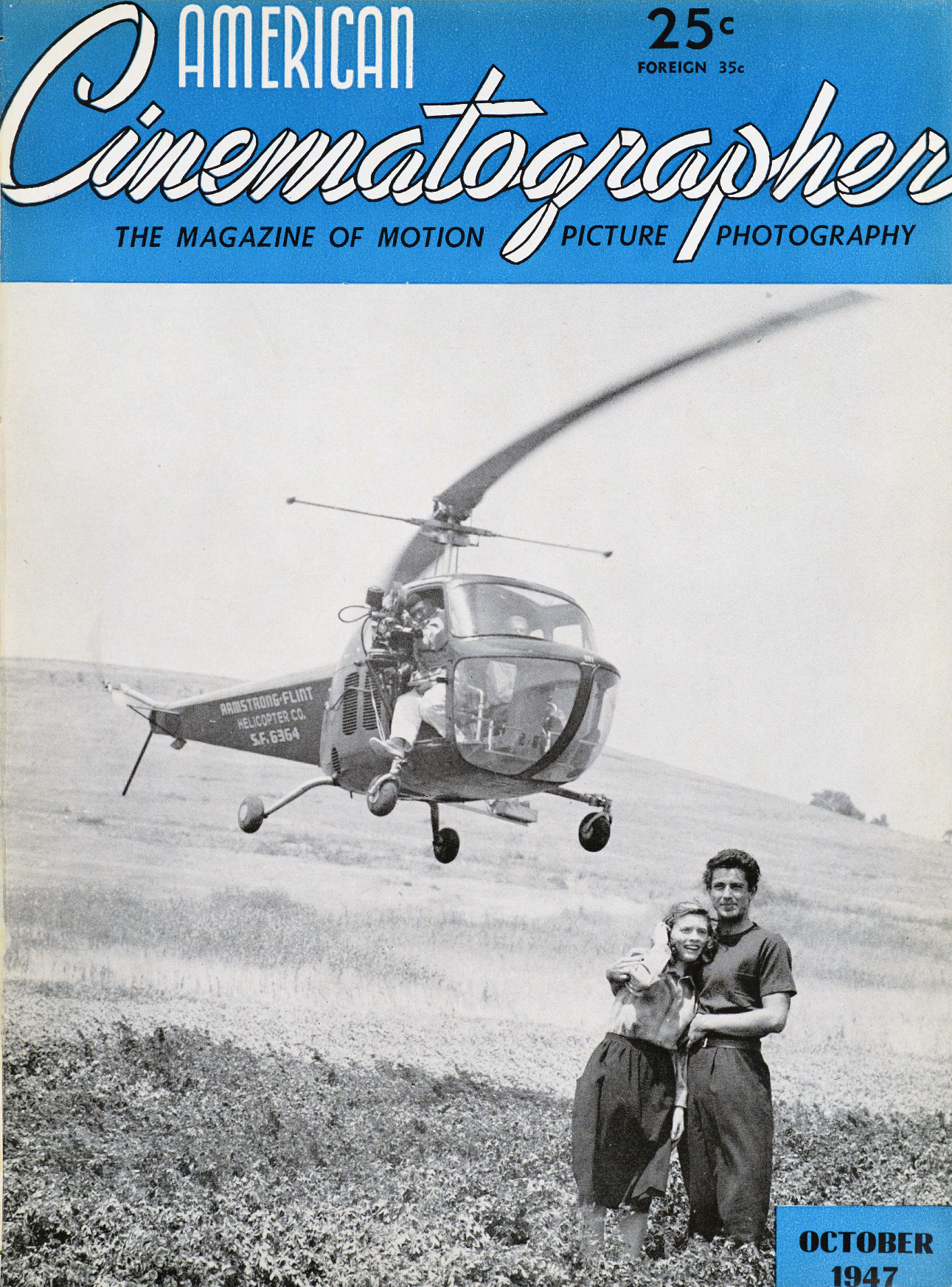

In the face of contemporary skeptics, the collective imagination of cinematographers is stimulated by new engineering developments that loom on the horizon. Not too far off is the "electronic camera." A compact, lightweight box no larger than a Kodak Brownie, it will contain a highly sensitive pickup tube, 100 times faster than present-day film stocks. A single lens system will adjust to any focal length by the operator merely turning a knob, and will replace the cumbersome interchangeable lenses to today. Cranes and dollies weighing tons will be replaced by lightweight perambulators. The camera will be linked to the film recorder by coaxial cable or radio. The actual recording of the scene on film will take place at a remote station, under ideal conditions. Instead of waiting for a day —or days, in the case of shooting with color — electronic monitor screens connected into the system will make it possible to view the scene as it is being recorded. Control of contrast and color will be possible before development.

It is not too difficult to predict the effect of such advancements on the production of motion pictures. Economically, it will mean savings in time and money. Since the photographic results will be known immediately, it will be unnecessary to tie up actors and stages for long periods of time. The size and sensitivity of this new camera will make photography possible under ordinary lighting conditions. Shooting pictures on distant locations will be simplified. generators, lighting units, and other heavy equipment will be eliminated, thus doing away with costly transportation.

In terms of cinematographic art, it will place a more refined instrument in the hands of the cameramen, an instrument of greater sensitivity and mobility.

Do you hear the skeptics shouting "IMPOSSIBLE"?

At the time of writing this essay, Leon Shamroy was serving as ASC President (1947-’48) and had built a reputation as one of Hollywood’s finest cinematographers.

A native of New York City, Shamroy was born in 1901 and highly educated, studying mechanical engineering at Columbia University. But he also had a passion for the movies.

He made his way out to Los Angeles at the age of 19, landing a job in the lab at Fox Film Corporation. After working as a technician for more than a decade, he gained experience as a camera assistant and shot his first films in the 1920s, before striking out with Robert Flaherty to photograph a documentary on Native Americans of the Southwest. After a series of freelance assignments, Shamroy continued with non-fiction work, shooting in Asia and the Middle East for two years.

Returning to Los Angeles, “Shammy” shot such pictures as Women Men Marry (1931) and Stowaway (1932) and was invited to join the ASC in 1932.

In 1939, he became a staff cinematographer at 20th Century Fox, where he remained until his retirement in 1969.

While an expert in black-and-white photography, demonstrated by such films as The Young in Heart (1938), The Gentlemen from West Point (1942) and Prince of Foxes (1949), Shamroy was renowned for his expressive color work in films including Down Argentine Way (1940), David and Bathsheba (1951), The Robe (1953), The King and I (1956), South Pacific (1958) and The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965).

For Shamroy, the unique photographic demands of Planet of the Apes (1968) represented a challenge — plus an opportunity to explode the myth that he was essentially an “interior” specialist. And for the film’s first act, in which marooned astronauts trek across an unidentified planet, he and director Franklin J. Schaffner scouted locations near Lake Powell on the Colorado River in Utah and Arizona.

“We were looking for a landscape weird and unearthly enough to suggest the possible terrain of another planet,” Shamroy explained. “The surface topography had to include formations that appeared tortured, chaotic — yet with a certain heroic, majestic scope. We also hoped to find a place where the earth was a ghostly gray-green color, rather than the characteristic red.”

Moving cast, crew and equipment into this desolate location was a major undertaking. “We could build a road part-way, and from that point on we had to hoof it for miles. People were passing out from the heat. It was the roughest filming experience I’ve ever had, but was worth it to be able to photograph the action in that wonderful terrain. God is a helluva set designer!”

Earning a staggering 18 Academy Award nominations, Shamroy took home Oscars for The Black Swan (1942), Wilson (1944), Leave Her to Heaven (1945) and Cleopatra (1963).

In 1960, he was also honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.