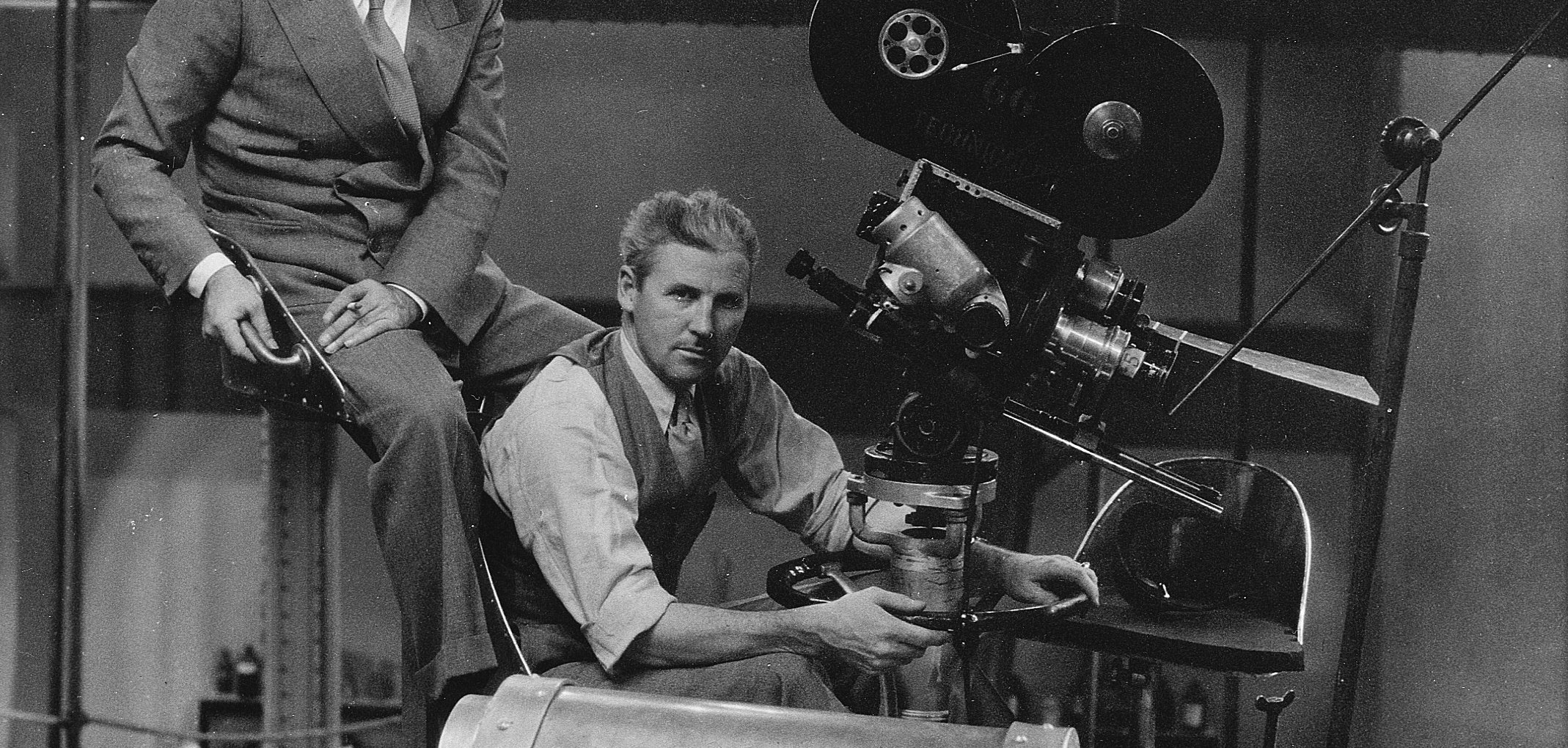

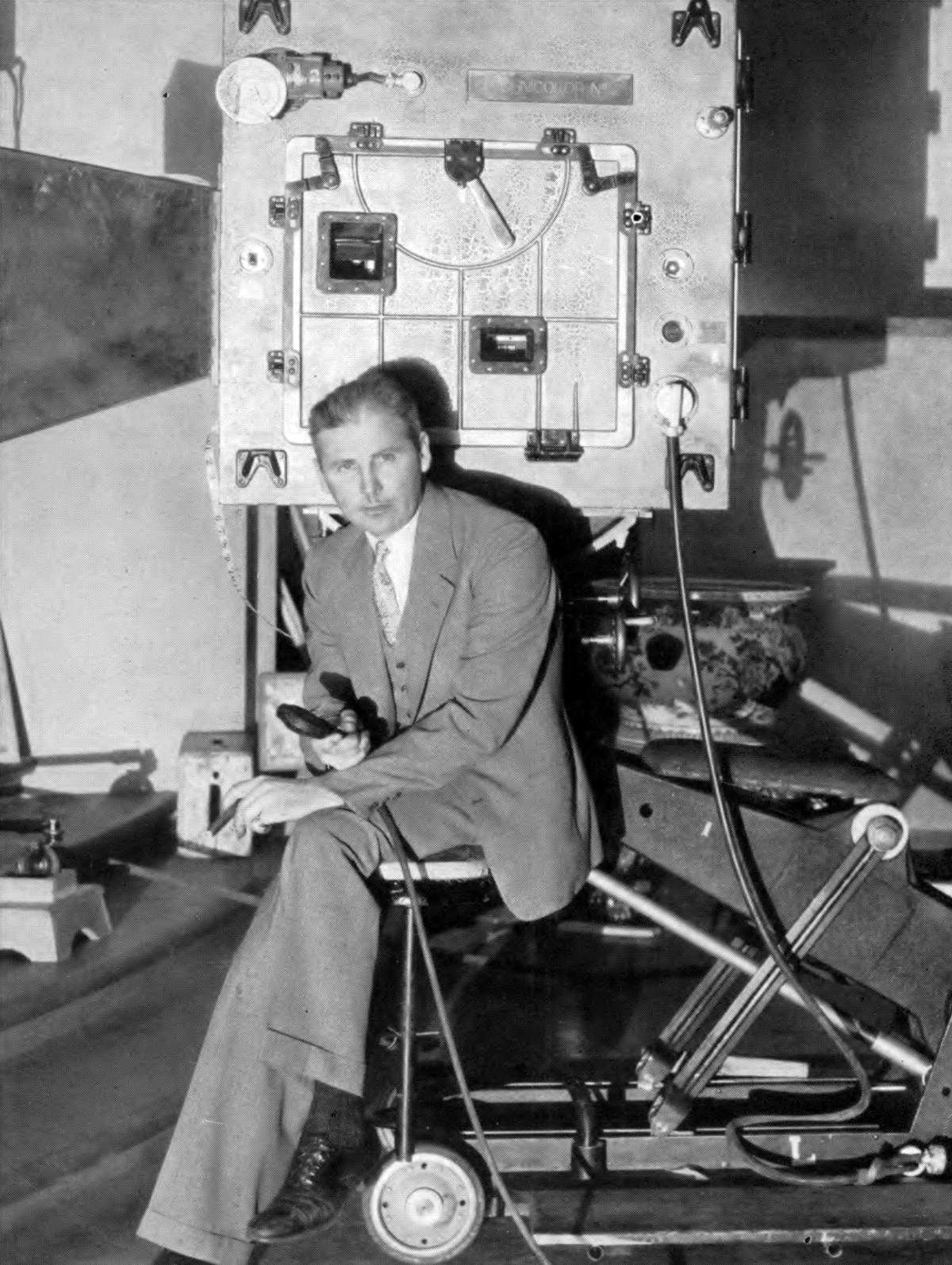

Aces of the Camera: Ray Rennahan, ASC

A 1941 profile on the expert cinematographer who excelled at shooting Technicolor.

“Aces of the Camera” was a profile series that ran in AC for several years starting in the early 1940s. This article was originally published in AC March 1941.

When you think about natural-color cinematography you think about Technicolor — and when you think about Technicolor, you think almost as inevitably about director of photography Ray Rennahan, ASC, who for nearly 20 years has been the mainstay of Technicolor’s photographic staff. Back in 1921 he photographed the first Technicolor feature ever released —Toll of the Sea. Six years ago, in 1935, he photographed Becky Sharp, the first feature made by Technicolor’s modern three-color process. And almost exactly one year ago he received the industry’s highest photographic honor — the Academy Award — for his participation in Technicoloring Gone With the Wind. During the years between, he has specialized in color cinematography to such an extent that he has photographed or participated in photographing a great majority of the outstanding color productions made.

But if you try to single him out with some such poetic title as “the granddaddy of Technicolor cinematographers,” Rennahan is likely to rebel. He’ll smilingly point out that at 45 he’s in the wrong age-bracket entirely for such a title. “And besides,” he’ll add, “I’m not actually the senior cinematographer in point of years with Technicolor: that honor properly belongs to George Cave, ASC, who, though in recent years he has been a Technicolor executive, was for many years a cinematographer — and a good one. George photographed the firm’s first tests, and their first feature, too, in the quickly-abandoned additive two-color process. I came on only after the two-color subtractive process had been developed to the point of being commercially feasible, and [Technicolor co-founder] Dr. Herbert T. Kalmus came to Hollywood to make a feature.

“But there’s no particular point in digging back into that ancient history. Technicolor and all of us who have been associated with it have come a long way in these last 20 years; but I think that all of us, from Dr. Kalmus right on down the line, are a great deal more interested in the achievements yet to be made than in anything we’ve done in the past.

“That’s not saying we haven’t made progress! Even in the past six years, since the present three-color process has been in use, we’ve seen changes, not only in the process itself and the results we can get with it, but in the industry’s attitude toward color. Six years ago, making a color feature was an adventure, and more; to the producer it was a gamble, and to the production crew on the set it was a headache. Today the industry has learned to take color in stride. The producer knows that color, intelligently used, definitely adds to the box-office appeal of a good picture. And the production personnel on the set know they can do anything with Technicolor that they can with black-and-white — and do it more effectively because of the added element of color.”

Rennahan considers his long specialization in color a definite asset. “Of course I’ve shot some black-and-white now and then,” he remarks. “I did, for instance, when we were recently down in Mexico City on location for my present picture, Blood and Sand, and some monochrome background and stock-shots had to be picked up for the studio. As a matter of fact, I’ve shot just enough monochrome to know I can handle it better than I ever did before, just be cause of the training I’ve had with color."

"But I’m always glad to get back to color; it’s so much more satisfying."

“And,” he points out, “there’s a definite advantage to working as we Technicolor cinematographers do. We do get around! I think we get a greater variety of work and experience than almost any other group of cinematographers. It’s not only that we’re constantly working in different studios, on different pictures, and with different production cinematographers as partners. We also run the fullest possible range of production conditions and subject-matter. One day, for instance, I may be working on a really big major production like Gone With the Wind or my present assignment, Blood and Sand: a few days after that assignment closes, I may be sent to some other studio to direct the photography of a little three- or four-day short subject, or even a commercial film, in either of which instances time and resources are likely to be as limited as they were abundant on the major studio ‘special.’

“This constant change means you don’t have any chance of getting into a rut, technically or artistically. One day you’re working on a big picture where time and money hardly count, and the main thing is to achieve perfection in each scene. The next, you have to slap it out fast, cutting corners wherever you can to save a few moments or a few dollars — and the results on the screen have still got to be good!

“About the only variable we miss that a freelance monochrome cinematographer has to contend with is constantly changing from the processing standards of one laboratory to those of another. All of our work must of course be processed by the Technicolor laboratory. Still, what with advances in negative sensitivity and constant improvements in negative processing and printing methods, our lab has certainly done its bit to keep us from getting mentally stagnant!

“And I think everyone will agree that that laboratory has done a remarkable job. When you consider the technical problems involved in any type of color photography, and the variables involved in developing three negatives, balancing prints from the three to form a complete three-color positive, and the innumerable peculiar habits of even the most perfectly standardized dyes, you’ll realize what a job they have. And in spite of it all they’ve refined the process to a point where today we accept consistently good color-prints as a matter of routine.

“Even within the past couple of years, processing improvements have made an enormous difference in the freedom with which anyone who photographs Technicolor can work. Just a few years ago, for instance, shadows were something which, unless you were in a position to gamble on results, most of us preferred to avoid. Today we can use shadows in Technicolor — not only that, but they are richer than the best obtainable in black-and-white, for we can get real, healthy blacks, and add to it the heightening effect of color-contrasts. Any colored object — a face, a hand, a dress — stands out more vividly when contrasted with one of the velvety shadows today’s Technicolor can give you.

“And speaking of faces, there’s one thing that tends to suffer under some of the production methods used by some studios making Technicolor pictures today. Any cinematographer knows the importance of make-up and of thorough understanding and cooperation between the make-up artist and the director of photography. In Technicolor, it’s doubly important, the more so because good color make-up is a comparatively new thing, and one which can be learned only by experience. I don’t think the make-up artist lives who can do a really satisfactory job on his first color picture. He’s got to learn the restraint necessary for good color make-up.

“Of course with the constantly increasing number of color productions being made, more color-trained make-up artists are being needed, and men who have not previously had experience with color make-up must somehow be given the chance to get it.

“But when, perhaps only a short time after finishing a Technicolor picture at a studio, you return to that studio for another picture and find an entirely different man in charge of the picture’s make-up — well, it doesn’t seem quite logical to me. Especially when you find — as I have on many occasions — that the make-up man you worked with before, and carefully trained in the requirements of color make-up — is still on the studio’s payroll and without an assignment. You’d think the studio executives would naturally put the man with color experience on their color production, wouldn’t you? After all, in addition to deciding in the first place to enhance that production with color, the studio has gone to considerable trouble and expense assigning a production cinematographer like Ernest Haller, ASC or Ernest Palmer, ASC and a Technicolor cinematographer like me or one of the other Technicolor staff cinematographers to the picture. We’re supposed to see to it that the players’ faces are presented in color to the best advantage on the screen: but we can’t do it if those faces aren’t correctly made up.

“I’ll admit its all to the good that as many make-up artists as possible be trained in color make-up. But letting them teach themselves by trial and error on actual production doesn’t make very good sense to me. Wouldn’t it be a lot better to assign the man they knew to be experienced in color as make-up man on the picture, and then let the man they wanted trained work with him as a sort of junior associate? In that way, the production would be assured correct make-up and normal faces from the start, and the make-up man would learn by doing things the right way, rather than by hit-or-miss experimentation.

“Really, the day of radical technical experimentation in Technicolor is over. Of course technical advances are coming, but we’ll be able to take them in stride, Meanwhile, there have been enough Technicolor productions made in almost every major studio so that we’ve built up a mighty good backlog of technical knowledge. The technical factors involved in making a satisfactory Technicolor production are now almost as familiar as those involved in doing the same scene in monochrome.

“But speaking as a cinematographer, I’m very sure we haven’t even begun to scratch the surface of the things we, as artists, can do with color. All of us who have worked at all with color—and most of those who haven’t had that opportunity, as well — have ideas which, once the right production opportunity arises, we want to try out. With the constantly increasing number of Technicolor productions being made, the opportunities for putting into effect more and more of those ideas are going to present themselves. On some productions we can make use of the added literalness of color for greater realism. On others, we can make use of the added beauty of color for greater pictorial effect. And on yet other productions we can cinematic language, making use of color to heighten any dramatic mood, just as in monochrome we use lighting for mood and effect. The basic tools are ready and familiar in our hands: and as we learn to use them completely, I am confident we will see cinematography go on to new heights of beauty and dramatic expressiveness, for color, added to form, tone and motion, gives us the completely expressive medium of which for nearly fifty years cinematographers have dreamed."

Technical advances will come, but in the long run, we will find the real future of color cinematography in the hands of the cinematographers!”

Rennahan went on to shoot For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943), Lady in the Dark (1944), The Three Caballeros (1944) and numerous other films before moving primarily on to television work. He shot several episodes of shows such as Destry, McHale's Navy and The Virginian — but spent most of his TV years on one Western series in particular, shooting 103 episodes of Laramie.

He accumulated seven nominations in the "Best Cinematography, Color" category at the Academy Awards, including wins in 1940 (Gone With the Wind, shared with Ernest Haller) and 1942 (Blood and Sand, shared with Ernest Palmer).

Rennahan served as president of the ASC twice (1950-’51, 1965-’66) and passed away at the age of 84 on May 19, 1980.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.