Star Trek 50 Part IV — Star Trek Meets The Next Generation

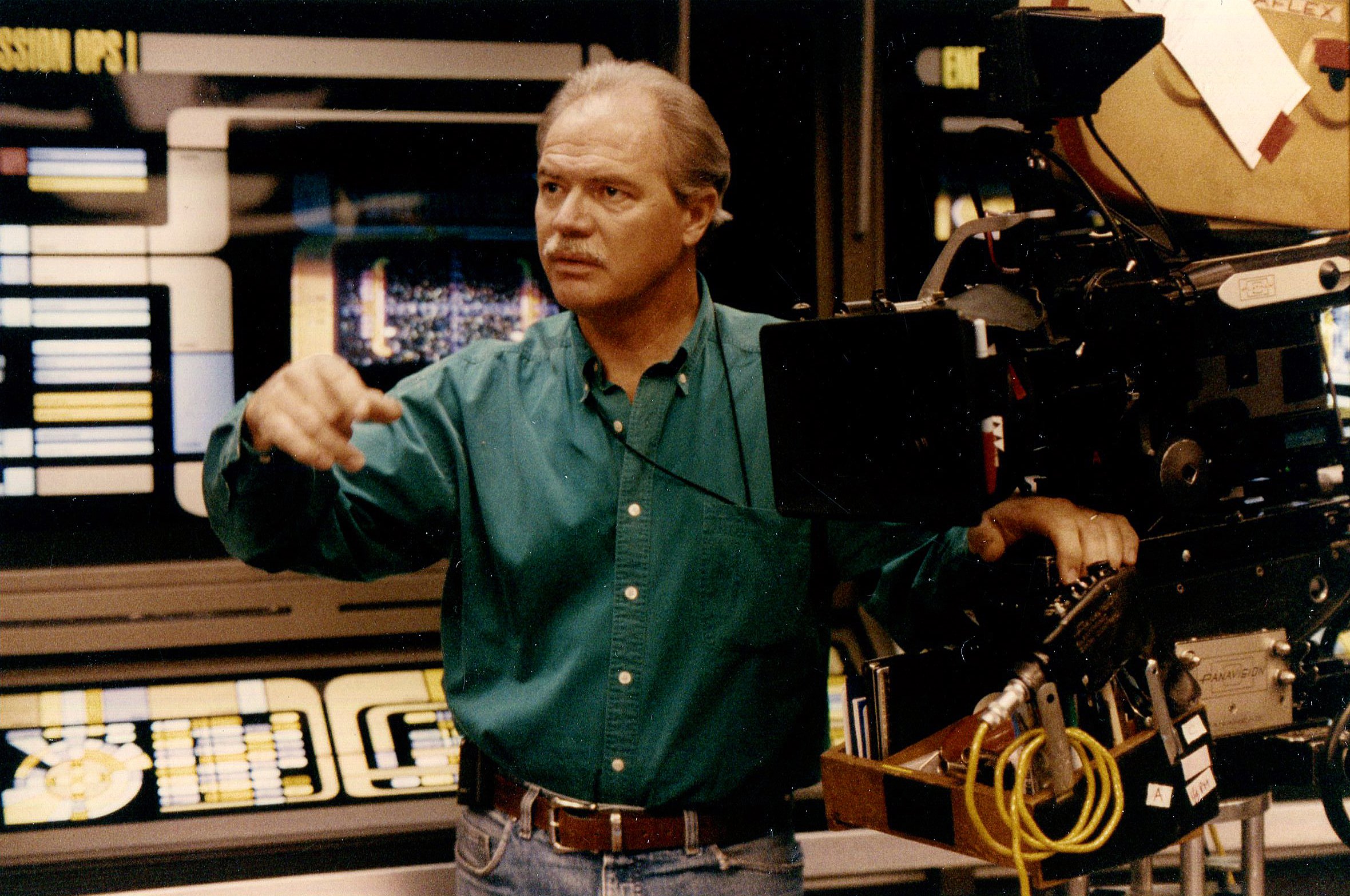

Cinematographers Gerald Perry Finnerman, ASC and Marvin Rush, ASC discuss their experiences at the Final Frontier.

The fourth entry in our 12-part retrospective series documenting 50 years of production and post on the Star Trek franchise.

Cinematographers Gerald Perry Finnerman, ASC (TOS) and Marvin Rush, ASC (The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine) bridge television’s generation gap and discuss their experiences at the Final Frontier.

When the first Star Trek pilot was filmed 30 years ago in 1964, creator and executive producer Gene Roddenberry wanted Lloyd Bridges to play the role of Captain Christopher Pike, but the actor turned him down. Jeffrey Hunter subsequently played the role, but the pilot never aired in its original form. Network executives felt it was too cerebral, and that Spock was too satanic for the public taste.

A second pilot, made in 1966, was to showcase Jack Lord in the captain’s role, but Roddenberry and Lord couldn’t come to an agreement. That opened the door for the inimitable William Shatner.

Since Star Trek first aired on September 8, 1966, there have been three additional TV series, seven feature films (with the latest due next month), well over 100 books, multiple videocassettes and laserdiscs, in addition to endless streams of merchandise. A poll several years ago indicated that 53 percent of Americans consider themselves Star Trek fans.

In 1987, Paramount Communications redefined the television landscape when they bypassed the three main commercial networks and released Star Trek: The Next Generation in first-run syndication. A slew of other original programs and movies made for first-run syndication have followed in its wake.

In many significant ways, Star Trek’s 28-year lifespan has encapsulated the contemporary history of television film. The original 1966 series was primarily photographed by Gerald Perry Finnerman, ASC. Star Trek: The Next Generation was shot by Marvin Rush, ASC, who subsequently went on to shoot Deep Space Nine, and is currently filming Star Trek: Voyager. The two collaborated last year when the original Star Trek cinematographer filmed many of the background elements used for digital compositing of Deep Space Nine scenes.

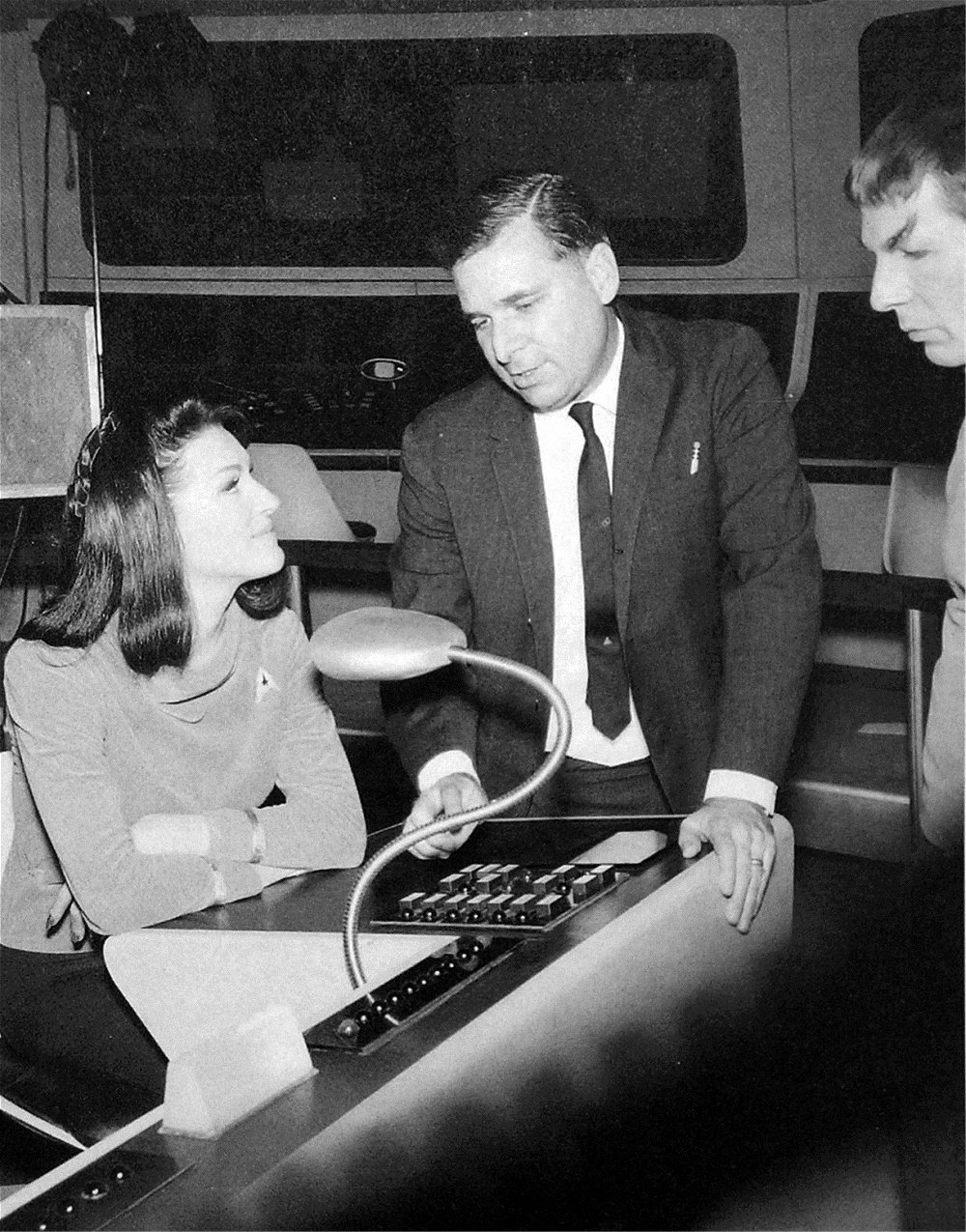

In a recent conversation in which the two compared Star Trek memories, Finnerman recalled his initial involvement with the show. “It was a fluke,” he says. “I was working with Harry Stradling [ASC] on Walk, Don’t Run in Japan. After we got back, we were working at Columbia for about a month. Harry came to me one day and said that Desilu was starting a TV series called Star Trek. They had asked his son, Harry Stradling, Jr., to shoot it, but he was already committed to Gunsmoke. I didn’t think I was ready — I was only 32 — but Harry encouraged me to talk to them. A Desilu executive said they would let me shoot an episode, and if they liked it, I could do the next one. I really wanted to work with Harry on Funny Girl, but he told me to try shooting Star Trek for 30 days. He said I could come back if it didn’t work out.”

Three days after he was hired, Finnerman was making suggestions. Scenes staged on alien planets were normally shot against a white cyc background but the setting was sterile. “It had no depth, so I asked if I could read three or four scripts in advance,” Finnerman recalls. “One script was a love story. I said we should use warm tones to symbolize love, because color affects people psychologically, the same way music does. Another story occurred on a villainous, nefarious planet. It needed cold colors that chill your heart.”

Roddenberry told him to shoot a small test, and director Joe Sargent was equally encouraging. Finnerman wanted to put some 10Ks up high, and cut gels for different color themes. He planned to have scoops shooting light up from below, which would allow him to blend different colors. A colored light was aimed at the cyc, and costumed actors placed before it for the test shot. The filmmakers liked the results, and three days later, one of the heads of production at Desilu came onto the set with an $800-a-week contract.

With that test shot Finnerman began to establish a Star Trek look. It wasn’t uncommon for him to use an 18mm lens, and occasionally a 9mm lens, to create a feeling of depth. More typically, he used 24mm and 28mm lenses.

“We used forced perspective,” he remembers. “If we kept the camera down low, with a wide-angle lens, we could put a fake rock or two in the foreground and make them look tremendously large. We also added colored gels to the lights, which helped to define the mood on different planets.”

Finnerman was shooting with a Mitchell BNC camera, mainly with prime lenses, and recalls using a zoom lens only twice. The film he was using, Eastman color negative 5251 with an exposure index of 50, “was slow, but it had wonderful saturation and a lot of latitude,” he recalls. “I shot a series of tests to see where my printing lights were. I ended up pushing the film about a half a stop.”

Finnerman recalls that he used 150 footcandles of keylights, which, combined with the authentically woollen costumes the actors wore in 1966, didn’t take long to overheat both makeup and actors.

The situation was a Catch-22 for Finnerman. At f2.3, the images didn’t have the definition needed to maintain a feeling of depth: ideally, he needed a lens stop of f2.8 or 4. But that would have required raising the level of light to 200 to 300 footcandles, which would have had cast members fainting left and right.

Finnerman, who describes himself as “a knickknacker,” was not a fan of flat lighting, and on Star Trek, which was hot on relatively large sets with an ensemble cast, he used crosslight before it was in vogue. It was never as simple as putting up a 10K and using scrims to reduce intensity. He usually worked with two or three crosslights, precisely placed, while keeping the intensity as low as possible and giving the assistant cameraman enough of a stop to carry splits.

Having been one himself, Finnerman understood what the assistant was up against. That’s one reason he used wide-angle lenses: if he had a 24mm or 28mm lens on the camera, Finnerman knew that the assistant had a fairly decent shot at carrying a split without causing either the foreground or background to go soft. That sort of technique was counterculture thinking for television production in 1966.

“I did a lot of little things,” says Finnerman. “I would put most of the light on the person in the background. Your eye always goes to the place that is brightest. If you have two people talking, and you play the person in the foreground down in lighting, your eye goes to the person in the background, and they both look sharp.”

Finnerman still has a number of letters he received from Roddenberry during this period. One, dated May 31, 1966, reads:

“Dear Gerry, I am very pleased with the job you are doing and with your people and their work. I’ve heard you make three or four suggestions to the director, [and they were] all well-taken, constructive and highly practical. This kind of creative thinking from your corner will make for a unity between episodes and guarantee that we get them done on time. Keep up the good work.”

“Those letters were wonderful,” Finnerman says. “I would read them to the crew, and it kept their spirits up. His kindness permeated throughout the crew. He was never negative. If there was something wrong, he would come to me and say, ‘You know, maybe next time you might think of something and approach it a little differently.’”

Star Trek, then as now, was filmed entirely on sets, and in the early days, Finnerman says, there was an amazing amount of jerryrigging.

“We had wind and rain scenes, and would invent lightning effects,” he says. “We didn’t have a lightning machine in those days. I’d take an arc and reverse polarity. When you do that, every time you press the striker down you get flashing effect. I knew I was going to burn the arc up, and the electrical department would go crazy. But I thought it was worth it artistically.

“Usually, when we did things like that, it was impromptu.” Originally, he recalls, the transporter room effects were to be done using dissolves. “The characters would just appear and disappear,” he says, “and I thought, ‘This is pretty insipid.’ What would be indigenous to this show was some type of lighting effect, so I had them drill three or four or five holes in the floor. We put lights underneath, and then I did the same on the top.

“It occurred to me when we shot it for the first time that I should have said something. I hadn’t discussed it with Gene, and I probably should have. But when he saw it, he asked, ‘How the hell did you do that?’

“I had a lot to learn, and believe me, I learned every day. When we filmed our part of the two-hour Menagerie episode, I shot a whole day of process scenes, used as flashbacks. I shot it without putting the correction filter on the arc for the projection machine, and when I looked at it, it seemed a little cold. I couldn’t figure it out. What I hadn’t done was put a yellow carbon in the arc to correct for the Kelvin.

“The next day when I went to dailies, we were looking at the flashbacks based on the original pilot. The people were normally lit, but the pilot was absolutely blue. I’m sitting there shuddering, and thinking, ‘Well, this is the last day of my three-year contract.’”

Finnerman recalls, however, that Roddenberry turned to him at that moment and asked how he got such a marvelous effect! “I said, ‘I don’t want to go into the details.’ Sometimes you can look like a fool, but other times they think you’re some kind of genius,” Finnerman says.

“On a show like Star Trek, you have to push the envelope. The result of playing it safe is a diet of pabulum.”

— Gerald Perry Finnerman, ASC

Rush notes that the blessing and curse of Star Trek is that it can’t look like other television programs. “I’ve screened shows that Gerry shot in 1966 and compared them to other programs. It had a very distinctive, very different look, and it was better because of the difference,” Rush says. “The colors were wild. It was a snapshot of the times with a futuristic twist. I think for a lot of reasons it became an icon. One of them is the fact that the stories had a moralistic point of view.

“There was one episode that Gerry did with Frank Gorshin, where his skin was half-white and half-black, and he hated the people who were half-black and half-white [“Let That Be Your Last Battlefield”]. It didn’t take a rocket scientist to figure it out, but it was considered daring. I hope the continuing work that we’re doing is as relevant. That’s for someone else to judge. If it illuminates issues, and makes people think, then we are doing something that might still be around in 25 to 30 years.”

While Roddenberry was dealing with themes that were decades ahead of contemporary thinking, Finnerman was inventing new ways of shooting film for TV. Star Trek was one of the first shows with natural-looking source light, for which he caught a fair amount of flack from the network. He was told that his lighting should be flat and that the key-to-fill ratio should never be more than 2:1.

“I would shoot with a six- or seven-to-one lighting ratio most of the time, and every lamp we hung was used for crosslighting,” he recalls. “I was even lighting with a ten-to-one ratio, and it held.”

“They also believed that you should never put color on people or anywhere else,” he adds. “I remember one chief engineer getting absolutely livid. It’s funny now, but I was only 32 years old, and it was my first job as a cinematographer. We were sitting in the projection room and he said, ‘Look at the color of that man’s hair, it’s red. You’re doing everything you shouldn’t be doing.’ I’d put color on the cyc to warm something up. He said it was unacceptable, but Gene stood up for me and said he liked it.”

Finnerman’s strongest influences were Burnett Guffey, ASC, an Academy Award-winner for Bonnie and Clyde and From Here to Eternity, and Stradling, whose Oscar-winning work on The Picture of Dorian Gray Finnerman especially admires. “Harry once told me, ‘When you take the lights around so far that it scares people, or it scares you, that’s when it looks good,’ and that’s what I used to do. I used to take that light way around until I got scared, and then it had dimension. That’s what Star Trek had: dimension. It wasn’t only the colors and the gimmicks, and the shaking of the camera and the ship and the lighting, because basically we didn’t have a lot of effects, except for the standard wind machine and the rain machines.

“I think much of the look also came from the placement of lights and the use of colored gels. We also saved the company a lot of money, since they didn’t have to paint sets to make them look different. We painted them with light. We changed walls from gray to blue to green, depending on the mood and what we wanted to say about that planet. One day we created a purple sky. Another day, the same set looked like a hot desert in March. A third day, it was deep blue. We did it with filters and lights.

“My father use to tell me about Josef von Sternberg [ASC], who prior to becoming a great director was a cinematographer. He wanted all white sets. Then he would come in and paint them with light. That was in the days of black-and-white, and it was a process of cutting off the light, dropping it by degrees with the use of scrims. When he had finished, he had taken a pure white set and turned it into a magnificent three-dimensional look. I took that approach on Star Trek. I wanted all my sets painted white, and then I would play with them, knocking off as much light as I wanted and adding colors. We did it in six days per show, and we always made our schedule.”

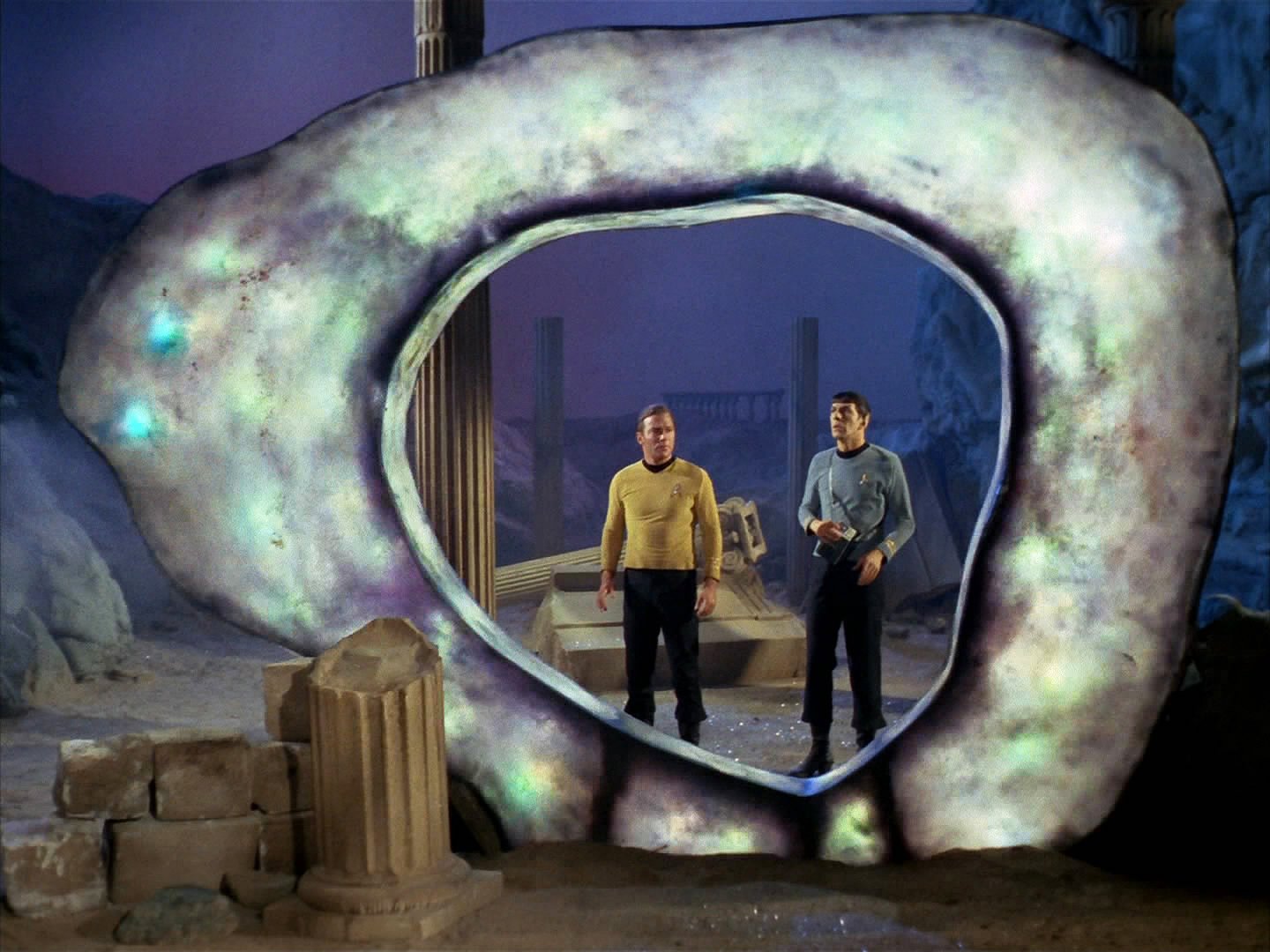

In order to make the ship’s bridge, the hub of the TV show’s action, believable, Finnerman took advantage of the set’s design features. “The set was 240 degrees,” says Finnerman. “You could see everything, so there was no place to hide lights except in the front, which meant that everything would have been flatly lit. The redeeming feature was that the set went straight up, like a chimney. I kept looking at that [overhead] opening. There was nothing in there, and I thought, ‘If I could drop something through that hole in the center, because you never see it I could put some kind of lights up there.’ I could crosslight the set, and just use front key for ambiance. It was soft light like Marvin uses today. I went to my key grip and said, ‘I have an idea, but I don’t know if it will work. It will probably look funny, but can you build me something like an octagon that I can drop through the roof, just out of frame? I want four lights on the bottom that I can point in different directions. It could be a piece of metal with eight arms coming out. Four on top, and four on the bottom.’ It looked like an octopus. From that angle, I was able to crosslight Kirk, Spock, Lt. Uhura and the others. It gave me backlight and dimension, and that really saved me. I tried to cut down as much as I could on frontlight, and that worked out very well.”

Finnerman considered it his job to help draw the audience into listening to the shows’ dialogue, which continues to be the core of all Star Trek stories, on film or television. “Gene Roddenberry wrote wonderful dialogue,” says Finnerman, “and all of the actors had stage experience. That helped. They delivered their lines in ways that locked the audience into their faces.”

Marvin Rush enjoyed a similarly talented cast in Star Trek: The Next Generation. Patrick Stewart, who portrays Captain Jean-Luc Picard, was with the Royal Shakespeare Company for over 20 years. “Captain Picard’s character is memorable, and it’s rooted in [Stewart’s] theatrical background. I think there’s a certain amount of reality of character that you get from actors who come from the stage. That isn’t to say that you can’t get there another way, but it starts with that background.”

In the early days, Finnerman shot with Mitchell cameras, which are big and heavy by today’s standards. But he always kept the cameras moving. “That’s another advantage of crosslighting,” he notes. “It throws shadows from sound booms off the set. We could make 90-degree turns in any direction.

“My philosophy of lighting is to look for the source. I try to figure out where the light is coming from, and what the logic is. Usually it is obvious, unless you’re on a planet where there is more than one sun.”

— Marvin Rush, ASC

“I was always pushing directors to go a little further,” he says. “I’d say, ‘On this two-shot, when Kirk walks away from McCoy, we can dolly over and take him over to the bridge.’ They weren’t comfortable with that. I liked to see a scene flow for three or four pages rather than shoot a straight master and then break it into close-ups.”

“So many things you say ring true today,” Rush says to Finnerman. “We are still moving the camera and using crosslight. We still push in on a tight close-up during weighty moments when something significant is happening. The techniques you used are still going strong.”

Rush’s Star Trek voyage began when he was working at Paramount, shooting the sitcom Dear John. His only single-camera film credit was Frank’s Place, a critically acclaimed comedy series. Tim Reid, the star of that show, asked him to shoot a pilot for a one-hour drama called Snoops. Immediately afterwards, Rush was invited to interview for The Next Generation. Ed Brown, the original cinematographer, was leaving the show. Rush was interviewed by producers David Livingston and Rick Berman, both of whom were fans of the distinctive-looking Frank’s Place.

“Much of the credit [for Frank’s Place] belongs to Bill Fraker [ASC,] who filmed the pilot,” Rush says. “I did my best to copy the look he established. That was no small feat, because he’s a terrific cinematographer. In any event, they were fans of the show. They remembered episodes and things that I had done with lighting.”

Star Trek was, in more ways than one, a whole new universe for Rush. On Frank’s Place, he typically shot five pages per day. On The Next Generation, he was shooting eight to nine pages daily, and the workload included digital compositing and other effects, many of which were new to him.

“I had done some minor optical work here and there, including split-screens,” Rush says. “I knew a little about bluescreen, but that was about it. I was starting with a new crew and producers I didn’t know. I’d known Hugh Wilson, the executive producer of Frank’s Place, for 10 years. When you know the producer and the crew, you have tremendous creative freedom.

“I remember the first Star Trek episode I shot. ‘The Ensigns of Command.’ Stage 16 was our swing set stage. It’s the biggest stage on Paramount’s lot, and the set covered every square inch. It was a giant village. It was immense, and it had integral interiors. [Cinematographer] George LaFontaine [ASC, with whom he had worked as an operator] told me once that sometimes big sets are easier to light, but it was still intimidating.”

Finnerman recalled having the same discussion with Stradling some 30 years ago, when he was lighting the Covent Garden set for My Fair Lady. Finnerman asked how Stradling was going to handle that big set. “Harry said, “The bigger the set, the easier it is to light. Just watch.” He started in the back and worked his way forward.”

“My philosophy of lighting is to look for the source,” says Rush. “I try to figure out where the light is coming from, and what the logic is. Usually it is obvious, unless you’re on a plane where there is more than one sun. George LaFontaine also taught me that when I shoot daylight exteriors on a soundstage I should put the sun in the worst possible place — the most unattractive, most uncomplimentary place — and then word hard to fix it. The idea is that when you are on location, you can’t put the sun where you want it to be. I don’t always follow that philosophy. But you don’t put it behind the camera – instead, I use a three-quarter raking backlight, or a half-light, or maybe even dead backlight, if you want it to look like real sunlight.

“It’s the same with interior light sources,” Rush continues. “I figure out where the sources are, and play them so the scene is believable. I really hate seeing more than one shadow on a wall. I try to get directors to stage action away from walls. The further they stay away, the easier it is to keep shadows from dancing on the walls. I tell them it will look better, because there will be more depth in the scene, and I can make actors look better. Most of the time that’s a successful technique. There are times when someone has to be up against a wall for a story point, or because of the nature of the room. In that case, I light for one shadow.”

Rush marvels at Finnerman’s work with 50-speed film. “We’re shooting with a 500-speed film. The 5296 film changes the equation. I can light a big room with a 10K and a bounce card, and pull a deep stop. I can use a 12' x 12' grifflon that gives me a base level of fill light that is essentially shadowless. When I put a crosslight in for key, I’ve got a single source. That just wasn’t technically feasible when you did the original show.”

Finnerman observes that many sets on the new Star Trek series are self-contained, with overhead and side lighting. “The high-speed film is such an advantage, because you can create a much more natural look,” he says. “There was no way our sets could be self-contained with a 50-speed film. Today, you can light entire sets by bouncing ambient lights off walls.”

Rush uses two approaches to designing light into sets. One is to put neutral density filters on them until they are nothing more than accent lights. The other is to allow them to become part of the base light. When an actor moves close to one of these lights, it is used as a source for motivating crosslight hidden just out of frame.

“I don’t think anyone can explain the magic of Star Trek. It’s a small miracle.”

— Marvin Rush, ASC

Rush notes that the look of the bridge set for the Enterprise was fixed before he came onboard The Next Generation. Referring to Finnerman’s comments about the bridge set on the original show, Rush says, “They did the same thing on my show. They built a complete [muslin] dome over the set. There was no provision for any lighting other than the ambient light coming through the muslin. Putting lights beside the camera was totally unacceptable to me. Instead, we built some boards that could be clamped into the ceiling and created a lighting grid for the captain’s chair.

“To my knowledge, the dome had never been photographed. It was supposed to be an observation window. You looked straight up and saw a star field on the other side. But no director ever made use of it; no actor ever looked at the stars through this window. We took the plastic window out and put a lighting grid in its place. It was very small. We didn’t call it an octagon, but it did exactly the same job.

“Your bridge had an elevated area with a second deck,” Rush continues. “We had the same situation. The problem was how to put in light without having big shadows plastered on the back wall, which was made of plexiglass. It was a mirror-like surface.”

Finnerman nods in agreement. “Basically we think alike,” he says. “Another cameraman might have walked onto the original Star Trek set or onto the Deep Space Nine set and said, ‘This is the way it is, and I have to live with it.’ Our inclination was to say, ‘Let’s make it better. We can fix it.’”

Rush is reminded of a sequence involving removable panels on the back wall of the bridge set, designed to allow the crew to take reverse shots of the cast. (The set also has permanent side panels.) For one episode, the director wanted to stage a shot in front of one of those panels, but Rush knew the camera would be unacceptably close to the actress. He didn’t want to use a 24mm lens for a close-up in this particular situation, because he knew the results would be inappropriate. But the director didn’t see it that way, so Rush asked his key grip to cut a hole in a panel wall to provide a better vantage point for the lens.

“We have a hotline to the office,” he admits. “I could have called, but I didn’t want to take a chance on someone saying no, so we took the initiative.”

Finnerman interjects his belief that Roddenberry would have approved. “I made a lot of artistic decisions without sharing too much information in advance,” he says. “Otherwise, I’d have ended up playing it safe. On a show like Star Trek, you have to push the envelope. The result of playing it safe is a diet of pabulum.”

The two cinematographers also share the experience of filming elaborate alien faces. “We used to have trouble sometimes with prostheses,” says Finnerman. “They tended to absorb light, whereas a face reflects light. My eye could pretty well tell me it wasn’t going to look good. You would put a light on it, and it would go blue or green. I found a trick. I bounced light through a reflector, which made it softer. I also added a little diffusion and netting to smooth a prosthesis out, so you really wouldn’t know what it was.”

Rush can report progress in that area: “Michael Westmore is our chief makeup man, and he has earned several Academy Awards and several Emmys for his work. The technology for putting makeup on appliances has gotten a lot more sophisticated. We use the same surgical adhesives that doctors use to stick tissues together. They are remarkably sticky, and a tiny bit will hold on firmly. You [Finnerman] also had to use a lot more light, with higher temperatures, and that tends to make people perspire. One of the things we do is to keep the stages air-conditioned to a pretty good level. There are a lot fewer problems with prosthetics coming off. We also use diffusion. Last year we had a real problem. In fact, I talked with Gerry about it. I was having problems with Odo, a character on Deep Space Nine. Gerry suggested that I try some particular nets. I had used nets in the past, but it was amazing how much better it was. It got rid of those lines a lot better than the diffusion I had been using.”

Rush, who had followed Finnerman’s work for years prior to meeting him, also cites Leonard South, ASC as a mentor. “I did Foley Square, my last show as an operator, with Lenny. He taught me a lot. I always prided myself on composition, but if an actor moved, I’d move the camera to correspond with his movement.

“One day Lenny said, ‘You’re doing a good job for me, but you need to learn to let the actor move in the frame a little more. If you did what you’re doing on the big screen, you’d knock the audience right out of their chairs.’ It really surprised me because I’d been doing this for a while, and I thought I knew what I was doing. But Lenny operated the camera on all of those Alfred Hitchcock movies, before he became a cinematographer, so he really understands the art. I’ve really taken it to heart. I always tell that to our new B-camera operators. It’s a subtle thing, but when you compare two shots side by side shot by two different operators, it’s a much more elegant look. That’s what Leonard South taught me, and I’ll never forget it.”

Rush notes that one of the original episodes of Star Trek might typically have incorporated eight or nine optical shots, a very ambitious number in the 1960s. A Deep Space Nine episode could contain 50 or 60 composites. The two-hour pilot had more than 200, including motion control filmed on stage with actors, and dozens of split-screens and digital composites. The producers also integrated morphing and computer-generated images into the show.

“This use of technology makes it possible for us to do different types of stories,” Rush says. “Whole sets can be created without building them. We were able to do a lot of this optically, but now it’s quicker and more seamless.”

“I’ll tell you how far [effects work] has come,” says Finnerman. “One the original series, there was an episode with a split-screen, where I exposed half of each frame with Shatner, and used a black show card to cover up the other side of the frame. Then I rewound the film, put it back in the same camera, and shot the other side of the split-screen. George Méliès used that technique in 1900. We pulled it out of the air and hoped it would work.”

Another major difference between the production of the two shows is dallies. When Finnerman was shooting Star Trek, dailies were on film, and they were only open to Finnerman, the producer and the director. The new Star Trek shows have open video dailies to which everyone is welcome. The only restriction is that everyone must watch the same TV monitor, in the same room, so that they see the same images.

What hasn’t changed, Rush points out, is that the characters are wearing funny outfits, talking about places that don’t exist, and shooting silent guns that don’t have any recoil. There is a very fine line between creating a new reality and seeming silly, he says.

“What’s happening in front of the camera must seem absolutely real to the audience. The people who speak the lines must absolutely believe what they say. They have to make the audience believe that there really is a place called Argon Nine, and that the characters have been there.

“Whenever possible, sets are built in 360 degrees. There are no three- or four-wall sets. Instead, there are six-wall sets, including the floor and ceiling. Everything is shootable in any direction. If a director wants to do a 360-degree dolly, it’s no problem. He can show the audience the ceiling and the floor to help develop a sense of place.” The trick, Rush says, is to design the base light into the sets. That way, he doesn’t have to light every shot from black.

“We put a ceiling grid with 8K soft lights (on the Promenade set),” he says. “The light went through muslin. We built some other grids with color-balanced fluorescent tubes. The 8Ks were divided into circuits. That allowed us to divide the Promenade into sectors. They were all on a computer dimmer board handled by the gaffer. I told him what I wanted, and he did it. The point is that these panels could be photographed. They were a part of the set, and they contributed to the ambience. The main lighting units were generally just at the edge of the frame, two or three degrees away. With this lighting structure, we could freely have 360 degrees of coverage.”

As Finnerman had on the original show, Rush designed a signature look for key characters in the new Star Trek films. For example, Worf, the Klingon security chief played by Michael Dorn, has incredibly deep-set eyes.

“He typically stood as far back in the Enterprise bridge as you could possibly go, and he has a dark complexion,” Rush says. “The android, Data, has a yellow face, which was about a stop overexposed when he stood in a shadow. That was a tough combination for any two-shot. I used a 4K softlight with a long snoot for Worf. We called it the ‘Worf light.’ It sat on a pie place on the floor, and it basically came up to the eyeline. It was well below the lens, because if you put it on even with the lens, and Michael lowered his head at all, his eyes would go completely to black. We used a net on Data, about a single’s worth, to bring him into harmony with the rest of the set.”

“I use the same technique on Benjamin Sisko, the captain on Deep Space Nine, that I had on Picard,” he continues. “We set the key in such a way that wherever he turns, it catches just the socket of the downstage eye. It lights half the face and the bridge of the nose catches just the eye socket. I didn’t invent it, but it’s something I use very often on those characters. It’s difficult to explain, but it feels and looks right.”

“Another Rush contribution to the look of the new shows Star Trek shows is darker set walls. He explains that if you have darker walls to begin with, they don’t tend to reflect as much of the bounce fill light he uses. This allows him to fill with ambient bounce light without using scrims and flags to tone down bright walls, which in itself creates more contrast.

On The Next Generation, Rush made occasional use of half-light. On Deep Space Nine, he started keying with half-light when he designed his approach to filming the show. He used half-light on faces, sometimes in combination with an eye light he calls a “hot dot.” The “hot dot” technique combines a bounce card with a small light, usually a tweenie. He positions it low and behind the camera. “I’m not a big fan of Obie lights,” he says. “They can get too bright if the actors get too close. If they are a few feet away, they are too dark. We do the same thing with a bounce card and a light. Even if someone is too far away, there are generally no exposure problems. That’s because of the way light works: the further you back off, the smoother it gets. That doesn’t work for a dolly shot, and for that reason sometimes we use an Obie. But generally, we create eye light with a fluorescent that we can mount on the back of a magazine. It’s right over the top of the operator’s head, and it shines on both sides of the magazine. It has a dimmable fluorescent valve built by my gaffer.”

Rush says that he got lucky on Deep Space Nine: the cast had some difficult faces to photograph, but there were also many faces that can take light from a variety of angles and still look good. “The cast you work with, and their faces, determines to a large extent what you can and can’t do, certainly for close-ups. I usually give the actor something to look at when we are staging a scene. For example, if there’s dialogue, and we are coming for a close-up on one actor, I’ll ask the other one to lock in on the eyeline. I’ll show them where it is, and bang, they’ll come right to it.

“I tell them, ‘If you come right to this point here, your face will light up in a way that will really reach out to people. If you go past it, it won’t work.’”

Finnerman comments, “That’s very interesting. When I was doing Star Trek, I used classic black & white lighting techniques. Today, lighting styles have changed considerably. It’s much more of a natural source look. I find myself doing things today, like bringing light into a face at a lower angle, that I wouldn’t have done then.”

Ask Rush about the keylight level he used on Deep Space Nine last season, and he’ll tell you he doesn’t read footcandles very often. He thinks in terms of stops. He rates the 5296 at an exposure index of 400, about a quarter-stop overexposed. The lens stop is generally around T3 to 3.2. He estimates that his keylight is 30 to 35 footcandles. That provides some frame of reference when you compare it to the first Star Trek shows.

Rush notes that the bounce light he tends to use requires more wattage, and one of his tricks to keep the stages cool is to use a tiny piece of foam core or show card stapled up in a corner. He puts an Inky on a pie plate, on a riser, and shoots the beam into the foam core. The result is sufficient to light a little corner of a set.

“That option wasn’t available to you,” he says to Finnerman. “You simply couldn’t approach a little hidden corner the same way that I can. I can tuck lights into small little areas, and they do a lot of work.

“Probably a lot of cameramen don’t use fluorescents as much as I do,” Rush continues. “We have rigged all kinds of fluorescents in various sizes, from tiny luminaries to big eight-footers. I also use quart light, and just about everything Mole Richardson makes.

“There is so much more flexibility today,” he says. “Back lighting is a lot simpler. Before, you had to hang a junior fairly high up. It’s pretty bulky, and it had to be supported. It stuck out from the wall a ways, and it had a set of barn doors. Today, I can take a little piece of foam core, about four inches long, staple a six-foot fluorescent tube against the wall, angle the bracket in the right direction, and I’ve got seamless backlight.”

What was it that made Star Trek so special that it is more popular than ever some 30 years later? The richness of the concept, the synergy between the characters, and the remarkably imaginative stories conceived by Roddenberry are a major part of the success, but Finnerman believes there is more to it. “We think visually, and that’s synonymous with the magic of Star Trek,” he says. “Images augment the words like pieces of a puzzle.”

Rush adds, “I couldn’t agree more. I don’t think anyone can explain the magic of Star Trek. It’s a small miracle.”

“Having the privilege of working on this show has made me think a lot about the future. I’m sure that Gerry had no idea that people would be watching his shows 25 to 30 years after he shot them. It is a real tribute to him that they have stood up so well. I hope what I’m doing now will be aired for 25 to 30 years. I always think, ‘I’d better do a good job, because if it’s horrible, I’m going to be looking at it for 30 years.’ It’s important not to think of this work as a disposable television show.”

“It’s funny,” says Finnerman, “I’ve been very fortunate. I shot some very good features. I have 10 Emmy nominations, and I won once for Ziegfeld. Sometimes, people ask me about Moonlighting, but usually it’s Star Trek. I still get letters about Star Trek. That’s what people remember.”

This story retains the original text and style as it was originally published in American Cinematographer, October, 1994.