Aces of the Camera: William H. Daniels, ASC

The esteemed cinematographer was well known as Greta Garbo’s favorite talent behind the camera.

“Aces of the Camera” was a profile series that ran in AC for several years starting in the early 1940s. This article was originally published in AC Jan. 1941.

In the musical world, there are a rare few musicians who have such complete technical and artistic mastery of their media that not only the general public but also their super-critical fellow artists point to them as supreme examples of musicianly attainment. So, too, in the cinematographic world, there are certain outstanding directors of photography whose work is eagerly studied by their peers as consistently flawless examples of what fine cinematography ought to be.

William H. Daniels, ASC is one of these masters of the camera. He is a cinematographer’s cinematographer. If you asked any member of Hollywood’s closely knit and professionally hypercritical camera fraternity — from directors of photography down to film-loaders — for a listing of the 10 best directors of photography, the name of Bill Daniels would stand high on virtually every list. Among the non-photographic members of the industry, his name would rate almost as high.

But from this don’t jump to the conclusion that Daniels’ camerawork is necessarily showy or spectacular. It isn’t, for Bill Daniels is too completely the cinematographic artist to permit it. Superbly pictorial when the occasion legitimately allows, Daniels’ camerawork is planned with but one end in mind: to present players and story so perfectly that the camera-treatment itself becomes merely the vehicle — although a perfect one — which brings story and characters to the audience. It must never call attention to itself.

Seeking this end, Bill Daniels has always striven to avoid what he considers the two greatest — though diametrically opposite — photographic pitfalls: on the one hand, routine, “formula” photography; on the other, exhibiting too spectacularly individualistic a style. He’ll probably hate me for saying so, but in seeking to avoid these pitfalls, Bill Daniels has developed a style completely his own. Two successive Daniels pictures may not look in the least alike, yet both will be instantly recognizable to the camera-minded viewer by the sure precision that marks every phase of their camera treatment — a certain singing smoothness which for all its variety of technique and artistic mood is as distinctive as anything on the screen.

Dramatically and photographically, Marie Antoinette had nothing in common with The Mortal Storm, Ninotchka or Rose Marie — yet all three of them share the imprint of the inconspicuously perfect execution which is Daniels’ professional signature.

What sort of a person is this man Bill Daniels? Tallish, ruddy-faced, with red-brown hair and mustache and penetrating blue eyes, the first thing you notice about him is that like some of the more bewildering Irishmen of fiction, he seems somehow to be smiling internally even when he is most soberly concentrating on some perplexing production problem.

On the set, he exudes a curiously intermingled air of deft, easy-going competence with a strong sense of nervous dissatisfaction. The latter, I think, is dissatisfaction with himself, for in more than a decade I’ve never known Bill Daniels to admit that he was fully pleased with his achievements. He’ll turn out a photographic job of Academy-Award caliber — and even amid the backslapping of preview or premiere, if you ask him what he really thinks about it, he’ll say it’s “Pretty fair — I think I got about half of what I was aiming at.”

But to his fellow workers, it’s another story. One member of the crew of his current production — his second at Universal after a long and distinguished career at MGM — summed things up this way: “I’ve seen lots of cinematographers with big reputations, but when you come to work with them, they don’t always live up to advance billing. But with this man Daniels, it’s the other way around. He came to this studio a stranger — but today every one of us who has worked with him is for him 100%.

"You see how he’s handling things over there now? Well, it’s the same all the time. He never puts on an act — never raises his voice or makes a fuss over anything. But, man oh man, how Joe knows his stuff! He seems to know instinctively just where every light should go, how strong it should be, how it ought to be diffused, and all that. I thought I knew lighting pretty well myself, but let me tell you, I’m getting a college education in the art of precision lighting watching him light even the most commonplace shot!”

Daniels is an inventive fellow, too. He has started more than a few photographic trends and gadgets that have since become accepted practices in the industry. Characteristically, they're largely simple, commonplace bits of logic which, once you see them applied, make you wonder why you didn’t think of them yourself.

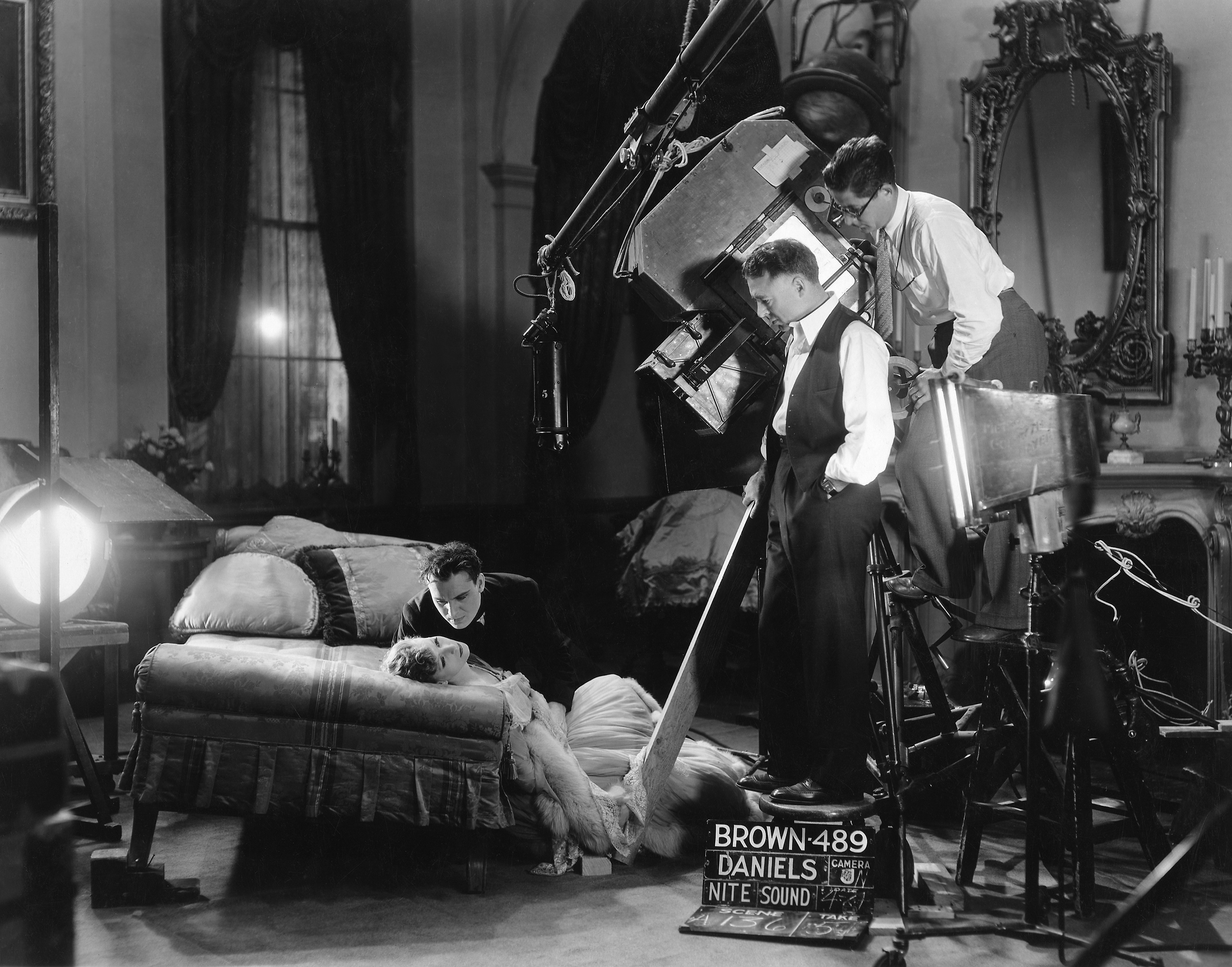

One of them was his celebrated bicycle horn. It began several years ago when he was filming (as he did for some 15 unbroken years) one of Greta Garbo’s productions. In that troupe, as in most others, while the directors of photography lights the set, the stand-ins take the places of the principal players, who in turn take it easy in their dressing-rooms. When the lighting is completed, the cinematographer usually passed the word verbally to the director, who in turn sent an assistant to summon the stars for final rehearsals and the actual “take.” But this verbal word passing took time and added a note of confusion to the otherwise orderly routine of production.

So Bill bought a bicycle horn and attached it to his camera-blimp. Then when his preliminary work was over, he could simply reach up and squeeze the bulb, and a few peeps on the horn gave everyone the signal at once. The stand-ins would step out, Miss Garbo would take her place before the camera — and production would go on with a minimum of confusion. Soon cinematographers in most of the other major studios had fitted their cameras with similar hooters. But about that time, Daniels discovered the drawback of that horn system — in his case, Garbo’s sense of humor. When she felt the waits between scenes were too long, she took pleasure in stealing up behind Daniels — and squawking the horn herself!

Soon after, Daniels originated the “peeping microphone.” Often a directors of photography finds it helpful to survey a set through the camera’s focusing ground-glass while giving instructions to electricians, players, and others. But when his head is buried in a sound-proof camera-blimp, even the loudest voice won’t carry far. And Bill Daniels hates to raise his voice.

So he persuaded the sound department to install a small microphone inside his blimp, with an amplifier and loudspeaker mounted on the outside. Then, when he was peeping through his camera, he could issue instructions to anyone on the set quickly, easily, and intelligibly, no matter how large or how noisy the set might be. Again, similar gadgets blossomed out on cameras in almost every other studio.

Most recently, Bill has added a new gadget to his camera. Like many other cinematographers, he finds it useful at times to mount a few lamps on his camera for front-lighting close shots. At present, using Super-XX, he employs two — sometimes three — “dinky inkies” and occasionally a miniature “broad.”

Now when you have two, three, or four lamp-cables — to say nothing of the loudspeaker power-line and the camera’s motor-feed cable — trailing from a camera that is to be making an involved dolly shot, your crew has a most confusing mass of spaghetti to keep untangled.

So Bill decided to simplify the spaghetti situation. In a convenient spot at the side of his camera head, he has mounted a six-outlet electrical junction box. Into one outlet he plugs a power line. Into the remaining five, he connects short feeder cables leading to his amplifier, his lamps, and any other electrical accessories he may need. Recently, while making retakes of a high boom shot, he wanted to make a last-minute check on the scenes he was to match. His assistant passed up to him the light tests of the scenes involved, together with the illuminated light test viewing box. Twenty feet in the air, Bill calmly plugged the lightbox's feeder to his mobile supply panel — and without further fuss or confusion compared his lighting setup with the scenes he was to match!

Daniels was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1901 and started his film career in 1919 — the same year the ASC was founded. He passed in 1970 with 170 credits to his name. Many of his most famous films were released well after the original publication of this article, including Harvey, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, How the West Was Won, and Ocean's 11. During his illustrious career, he was nominated for four Academy Awards, winning Best Cinematography, Black-and-White for The Naked City in 1949.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.