Escaping From Chains: O Brother, Where Art Thou?

Cinematographer Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC departs from traditional methods on Joel and Ethan Coen’s O Brother, Where Art Thou?, using digital wizardry to lend the Depression-era jailbreak tale a customized look.

This in-depth look at the making of O Brother, Where Art Thou? first appeared in AC's October 2000 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

Someday industry aficionados may look back on Joel and Ethan Coen’s O Brother, Where Art Thou? as a landmark film that began to redefine the cinematographer’s role. Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC originally photographed the film in the standard manner at practical locations in Mississippi, but then retooled the film’s color palette with the latest digital technology, fine-tuning the look and image quality until it closely matched the Coen brothers’ vision.

Well-received at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, the picture is slated for U.S. release in December. Its title pays homage to Preston Sturges’ 1941 film Sullivan's Travels, in which a successful movie director who is tired of churning out mindless entertainment decides to make a “serious” film called O Brother, Where Art Thou? The Coens set their story in rural Mississippi during the 1930s, and it follows three convicts who escape from a chain gang and embark upon an odyssey filled with misadventures. One of the trio, Everett Ulysses McGill (George Clooney), convinces the others (John Turturro and Tim Blake Nelson) to help him escape by promising he will share loot he has hidden away from a bank robbery. McGill claims that the area where the money is hidden is about to be flooded, which lends the escape a sense of urgency. As the story unfolds, however, the audience discovers that McGill is lying. The truth is that his ex-wife (Holly Hunter) is about to marry another man; he only needs the other convicts to escape with him because they are literally chained together.

O Brother, Where Art Thou? is not the first time an entire motion picture has been digitized and then converted back to film for distribution. Gary Ross did it on Pleasantville (shot by John Findley, ASC; AC Nov. ’98), and Jon Shear color-timed Urbania, a Super 16 film, in a digital suite (Shane Kelly; AC May ’00). George Lucas digitized The Phantom Menace (David Tattersall, BSC; AC Sept. ’99), but his purpose was to integrate visual effects and live action components in literally hundreds of shots.

Although O Brother, Where Art Thou? contains a number of visual effects shots, those scenes were incidental to the decision to digitize the film. In fact, the Coen brothers saw the computer as just another tool for extending the art and craft of cinematography. There is more than a little irony in that decision, however, since neither the Coens nor Deakins think of themselves as digital mavens. In fact, the Coens still edit on a traditional flatbed console because they feel that it gives them more tactile control of the film.

Writer-producer Ethan and writer-director Joel began making movies in 1984 with the acclaimed thriller Blood Simple (which was recently rereleased in theaters in a special “director’s cut”). Their films typically explore the dark side of humanity and feature characters who stick in viewers’ memories long after the last flickering images have disappeared from the screen. O Brother, Where Art Thou? is Deakins’ fifth collaboration with the brothers, following Barton Fink, The Hudsucker Proxy, Fargo and The Big Lebowski. (He is currently shooting the sixth, The Barber Project [The Man Who Wasn't There].) Other notable credits in Deakins’ body of work include Sid and Nancy, Thunderheart, Stormy Monday, The Secret Garden, 1984 and The Hurricane. He earned a 1994 ASC Award and an Oscar nomination for The Shawshank Redemption, as well as both Academy and ASC Award nominations for Fargo and Kundun.

Also Read: Photographing The Shawshank Redemption

“Before I read the script [for O Brother, Where Art Thou?] Joel and Ethan told me they had a film they wanted to shoot in the South,” Deakins recalls. “They imagined something dry, dusty and very hot.” Texas was initially chosen as the primary location, but the filmmakers eventually switched to Mississippi. “I’ve worked in Louisiana and Alabama [on Passion Fish and The Long Walk Home,] so I knew that the region would be wet and the foliage would be various shades of lush green — and about half the picture would take place in exteriors.”

The filmmakers briefly considered changing locations again, but Mississippi’s unique delta landscapes drew them back. “It would have been a different scenario if we had been shooting in the winter or if we’d been able to take in fall colors, but our film was scheduled for a summer shoot,” Deakins recalls. “I had to find a way to desaturate the greens and give the images we were going to shoot the feeling of old, hand-tinted postcards, [which was the look] favored by Joel and Ethan.”

To prepare for the production, the filmmakers shot some footage at Griffith Park in Los Angeles, where the trees were particularly green and therefore similar to those they were about to be surrounded by in Mississippi. This footage was then subjected to a series of tests by Beverly Wood at Deluxe Laboratory. According to Deakins, tests such as bleach-bypass and ACE produced interesting desaturation but could not be applied in a selective way. The most promising option was a bi-pack system combining a black-and-white panchromatic dupe with the original color negative. Deakins notes that although this technique provided a great deal of control over saturation, it was not selective enough. “I remembered that some years ago, when we shot 1984, we’d had a similar problem,” he says. “We originally wanted to shoot in black-and-white, but the project’s backers wouldn’t allow it. Instead, we decided to go for a harsh, desaturated look using a bleach-bypass system at Kays Laboratory in Great Britain, where the staff was performing tests for us. The challenge was to create the very golden, colorful looks for the scenes that required them as a counterpoint to the starkness of the main body of the film. On those few scenes, we wound up using very heavy filtration to counteract the bleach-bypass.”

While doing tests at Deluxe for O Brother, Where Art Thou?, Deakins began to consider the new digital technology at his disposal. He was aware of Lindley’s experience on Pleasantville and knew of Cinesite in Hollywood, which handled all of the film scanning and recording on that project. He thought that if he could scan the entire film into digital format, he would have infinite control over the look in the digital suite, but he wasn’t sure it would be affordable. Deakins discussed the concept with the Coen brothers, who were familiar with the technique, and they asked him to conduct more tests.

Some of the negative from the Griffith Park tests was scanned into digital format with a Philips Spirit DataCine at 2K resolution using a proprietary look-up table developed for this application. Deakins viewed the digital images with Cinesite colorist Julius Friede. Together, they worked on manipulating the saturation of the images, and in particular selecting the greens of the trees and grass and turning them into dry browns and yellows. At that point, Cinesite recorded the digital file onto the same 35mm Eastman EXR color intermediate film (5244) that labs use for making internegative and interpositive masters for release printing. A Kodak Lightning film recorder with a high-intensity laser light source was used to convert the digital files to analog images on the intermediate film. The film was then processed by Deluxe in Los Angeles, which also made a work print.

The tests convinced Deakins and the Coen brothers. “They like to try new things,” the cinematographer says. “We knew it would be taking a risk, but Cinesite gave us a good price, and quite honestly it was the only way we could see of achieving the look that all three of us wanted.”

O Brother, Where Art Thou? was also the Coen brothers’ first experience shooting in a widescreen format (2.4:1 aspect ratio), which Deakins had suggested because of the importance of the landscapes and the epic nature of the story. He recommended shooting in the Super 35 format, in part because he liked the perspective rendered by the spherical lenses he’d used on Kundun. “Every film defines its own palette of colors and textures,” he says. “I didn’t want glossy images. The spherical lenses have the effect of pulling the audience closer to the characters; it’s more intimate [than anamorphic]. To my mind, the feeling of depth recorded on Super 35 would augment the picture-book quality of the story.”

Deakins worked mainly with a single Arri 535 camera and the new Cooke S4 prime lenses. “I think it’s important to work with the sharpest lenses you can get — especially if you’re going to convert the film to digital format — but that’s what I typically do anyhow. I rarely use filters to soften a look, so it didn’t affect my decisions [regarding] lenses and filtration.” The cinematographer notes that the Cooke lenses record “very clean” images with very little flare. A number of times he shot directly into the sun without any glare. There also were a number of night shots motivated by very bright flames, including burning torches. He says the pictures were sharp and clean with no double images or kickbacks.

After testing, Deakins settled on three film stocks. He used Kodak Vision 500T 5279 for night interior and exterior scenes, and Eastman’s EXR 5248 100-speed emulsion for most daylight exteriors. While shooting daylight sequences in shadowy forest locations, he sometimes opted for the 200-speed Eastman EXR 5293, which he also used for recording bluescreen elements of composite shots.

The entire film was storyboarded, right down to exact angles of coverage. Deakins says there was considerable discussion about the boards during preproduction. “We stayed pretty close to the plan, veering from it only when something spontaneous presented an unexpected opportunity.”

The locations in and around Jackson, Mississippi, were relatively bare, though there were some shacks and buildings that could have passed for 1930s structures. “We built a couple of sets in a warehouse, because the weather is a bit unpredictable in that part of the country at that time of year,” Deakins says. “But we were only rained out once — lucky, I guess!”

The camerawork in the film is more objective than subjective, revealing the story to viewers as if they are spectators rather than participants. Deakins offers that the result is almost like watching a play, although he notes that the picture also has moments that are like musical interludes verging on fantasy (a tactic previously employed by Deakins and the Coens in The Big Lebowski). “Those moments aren’t structurally necessary for the plot,” he says. “It is almost an operatic or circus experience, like a Fellini film in many ways.”

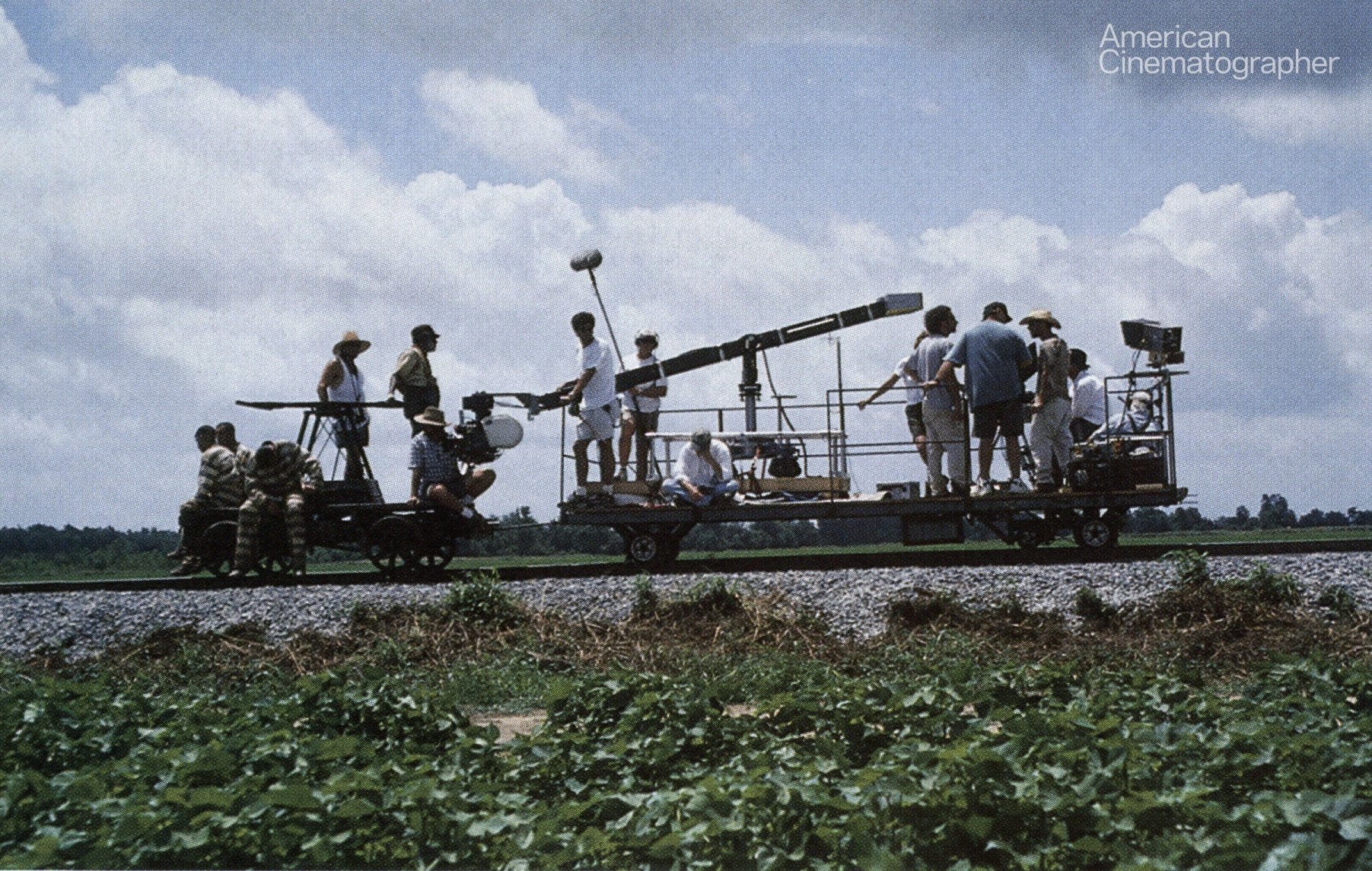

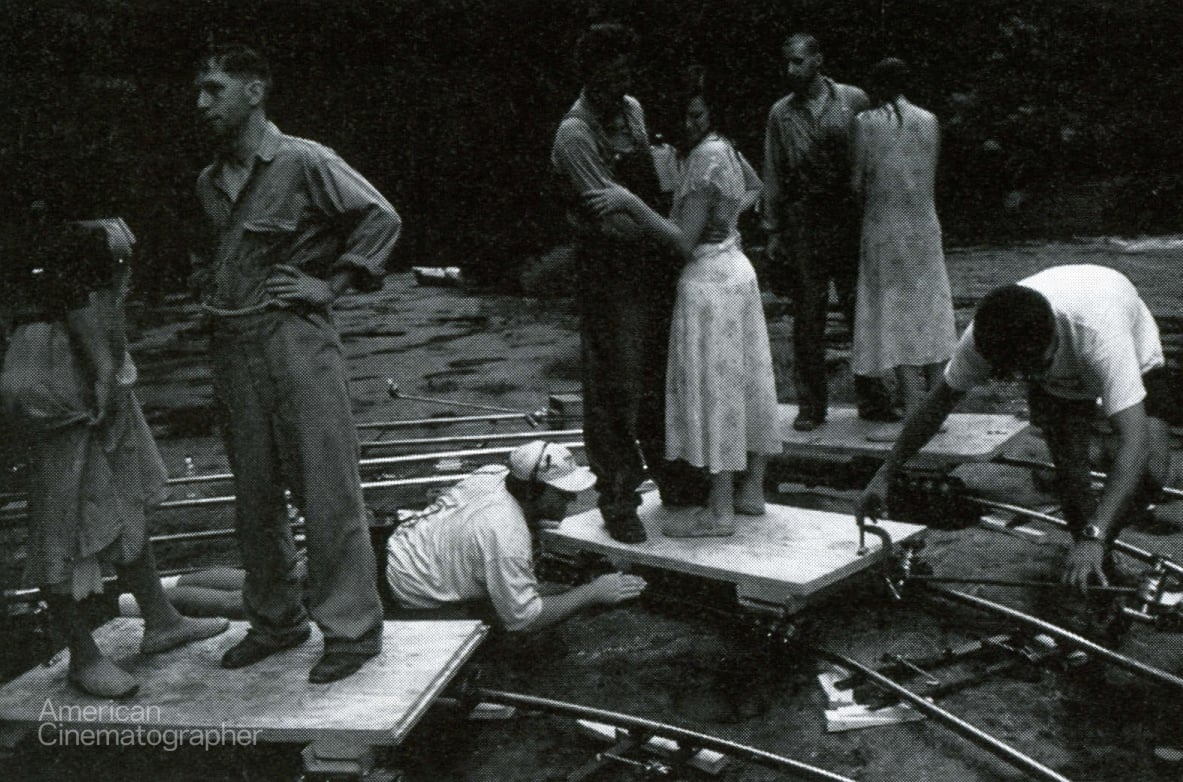

The camera is almost constantly in motion, though not as much as it was in, say, Barton Fink. “I generally prefer to be on a crane arm with a remote head, but sometimes it proved more practical to use a Steadicam over rough ground,” Deakins says. Much of the film was shot utilizing a Power Pod remote head and an Aerocrane jib arm. “ [That rig] allows a lot of flexibility in terms of camera movement, and it’s often a great time-saver. For one campfire scene, which leads the three main characters into a baptism ceremony, we shot all five setups with the Aerocrane on the same piece of track. We had been rained out all morning, but it brightened up enough in the afternoon to start shooting. We were in very thick forest; I knew it would be getting dark very early, so we had to work quickly.

“First, we did a pull-back with George Clooney to reveal Tim and John at the campfire, which became a wide shot of the whole scene,” he details. “Then we shot three close-ups in quick succession —just static shots with the Power Pod over the campfire. Next, we did a shot that circled around the group as they stood up to see these white-robed figures walking toward and past them through the forest. It was simple, really — as the dolly tracked back, the arm panned from one side of the group to the other, then around as the dolly was brought back in. The difficult bit was combining the panning of the arm with the panning of the camera so that it would look like one fluid move. We just made it as the sun sank from the forest!”

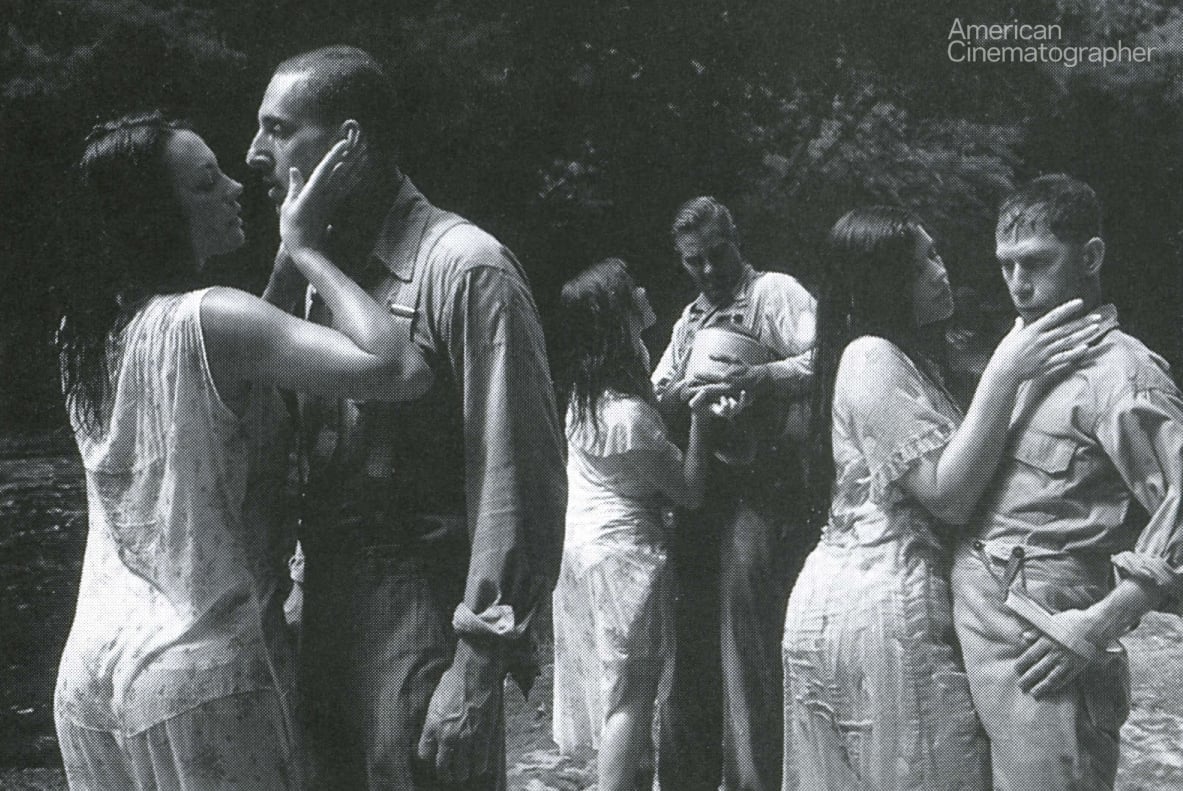

Deakins says Joel Coen wanted an interesting shot of the three cons as they followed the white-robed figures, who would lead them out of the forest to reveal the river and the baptism ceremony. To enhance the reveal, the filmmakers went from a shot on an 1T arm to one on an 85' Akela crane. “Trying to track an Akela through a swamp was not such an easy thing,” Deakins recalls. “We had to cut a road into the forest. My key grip, Mitch Lillian, decided to lay down 100 feet of railway sleepers to support the weight of the crane. Even those sank into the mud after a couple of takes, but we managed the shot with a slight wobble or two.”

The largest sequence in the film was actually shot at the Disney Ranch outside of Los Angeles. “We had some night scenes with a lot of lighting and effects, so it was obviously more practical to do those near the service industries,” Deakins says.

One of the scenes was a Ku Klux Klan rally involving some 350 dancing extras. “That sequence posed quite a set of problems,” the cameraman notes. “We had a large number of setups to do, and the choreography of the Klan members was going to be time-consuming. We chose a field backed by a tall, wide tree. The scene would be lit as if by the light from a 30-foot burning cross, and I knew I had enough room behind the tree to hide the large construction crane I would need to augment the firelight.”

To bring off the effect, Deakins used 10 Dino lights in a purpose built box truss that he suspended over the tree, in line with the fiery cross. “My gaffer, Bill O’Leary, had each bar of each lamp on its own flicker generator, and the whole unit was running at about 30 percent capacity on the dimmer. There was also Vi CTO in front of the lamps, which helped create the illusion of warm firelight.” The tree itself was front lit using 2K blondes that were also on flicker generators to give the effect of firelight coming from the cross. “Quite often I will use multiple sources to create the illusion of a big soft light,” Deakins notes. “I think during the shooting of the Klan rally I hardly used another lamp. Certainly very little changed from setup to setup — maybe some fill from a gold reflector or two.

“We just could not have made our schedule if the lighting had been complicated,” he concludes. “It was a case of an expensive rig saving time and money in the end.”

The cinematographer had a similar problem in Mississippi while shooting in an old theater. “This theater in Vicksburg was a historical landmark, so it was a hard rig,” he recalls. “Also, the ceiling was very low, so any light I used would fall into the wide shots if [the units were] bigger than a Tweenie. Again, we did not have the luxury of lighting each shot separately. I used an array of 65 Tweenies, which created the effect of a soft light on the theater audience and created a glow on the stage as well. If you look closely, you can probably count 65 shadows, but the audience will never see them!”

One of the film’s most intriguing effects shots occurs very early in the story. When the three cons break away from the chain gang, they attempt to board a rolling freight train. McGill jumps through an open boxcar door; a second con is halfway in and halfway out of the car, hanging on for life; and the third con is running alongside the car, trying to catch up. He finally stumbles and falls, dragging the other two out of the car. The sequence was dearly too dangerous to shoot with a real, moving train. Instead of using stunt doubles, the actors were filmed pantomiming the shot in front of a bluescreen. The moving train was filmed as a background plate, and the two elements were composited by Digital Domain.

Deakins spent about 10 weeks in a digital suite at Cinesite finetuning the film’s look after the negative was locked down and converted to digital format. The cinematographer reports that it was a learning process for both him and Friede. “We found that the more we tried to manipulate the image, the more noise and electronic artifacts appeared, and then we would have to rescan and retime the image,” he says. “In the end, we kept the manipulation to a minimum in order to maintain quality overall. We affected the greens and played with the overall saturation but little else. We only used windows, for instance, on a couple of shots.”

Sarah Priestnall, director of digital mastering for Cinesite, notes, “It was experimental in the sense that it was a learning process for all of us. Green is the most difficult color to deal with when you’re converting film to digital format.”

She adds, “Most people are going to focus on the use of this technology because it is new, but I think the most important thing is that everyone learned that the process can be very creative and intuitive, [enabling] cinematographers to create looks that may not be possible or practical otherwise.”

Deakins is frank in cautioning that there are still wrinkles that need to be ironed out before the digital intermediate process is as pliable as manipulating images for a TV commercial in a telecine suite. In one shot, for example, he noticed that an extra wearing an orange-yellow dress stood out from the crowd when the greens in the background were desaturated. He told Friede to tone the color of the dress down. That subtle color change now blends seamlessly with the rest of the shot, and the extra disappears into the background. However, Deakins notes that “you can’t take a cavalier approach and just say, ‘I’m going to change that green to bright red,’ because you can end up spending your life timing just one picture.” Deakins says, “The process is not a quick fix for bad lighting or poor photography; it is a tool to be used in the same way as any other tool.”

In retrospect, Deakins wonders whether the economic need to convert the film images at 2K resolution will impose some creative limitations. “There is a definite quality loss using the DataCine system, which is not even full 2K resolution — though none of us are unhappy with the resolution on the film. We found a slight loss of definition acceptable for this film, if not wholly desirable. I think it was pretty minimal, though, given that we were shooting Super 35 and could save an optical step at the lab by doing an anamorphic squeeze digitally.”

Priestnall believes that the challenges inherent in using digital intermediate technology for motion pictures will be resolved with time and experience. She says it would be impractical to scan, store and handle digital files for a complete motion picture at 4K resolution today, but notes that costs for computers and memory are coming down. She predicts that as the use of the technology becomes more prevalent, it could become more practical to work at full-film resolution.

All in all,” says Deakins, “it is a great technology and one that I feel will free me from the limitations of today’s highly contrasty and saturated stocks. However, there must be a way to view the images while timing them in a digital suite on a large, calibrated screen. It is all well and good to watch a 16-inch monitor in a telecine bay, but when the results are to be seen on a 40-foot screen, it is impossible to judge the image correctly without projection.”

The cinematographer says the Spirit DataCine is “restrictive, in that color timing is done from the original cut neg and not from a digital file. Thus, every correction or adjustment made involved the rescanning of the original negative. Naturally, it would make much more sense to be able to time the scanned file, especially if you are incorporating dissolves and CGI files into your master. I hope it will soon be cost-effective to output more than a single negative or positive, so that all release prints can be struck from a first-generation output and not from a dupe negative. This would certainly help preserve the image quality of the release prints.”

A New High Water Mark

By Ron Magid

Eric Nash, visual effects supervisor at Digital Domain, has supervised three shows in the past 11 months: Rules of Engagement and two upcoming features, Red Planet and the Coen brothers’ Depression-era opus O Brother, Where Art Thou?. The latter project only called for some 30-odd shots, but many were difficult simply because they had to look absolutely real. Nash says it was fine with him, commenting, “That’s the stuff I enjoy the most. The flashy science-fiction stuff is less appealing to me, partly because I spent so many years working on the Star Trek TV shows. It’s a lot more challenging and rewarding to create effects that very possibly could be real; the bar is that much higher to make them invisible.”

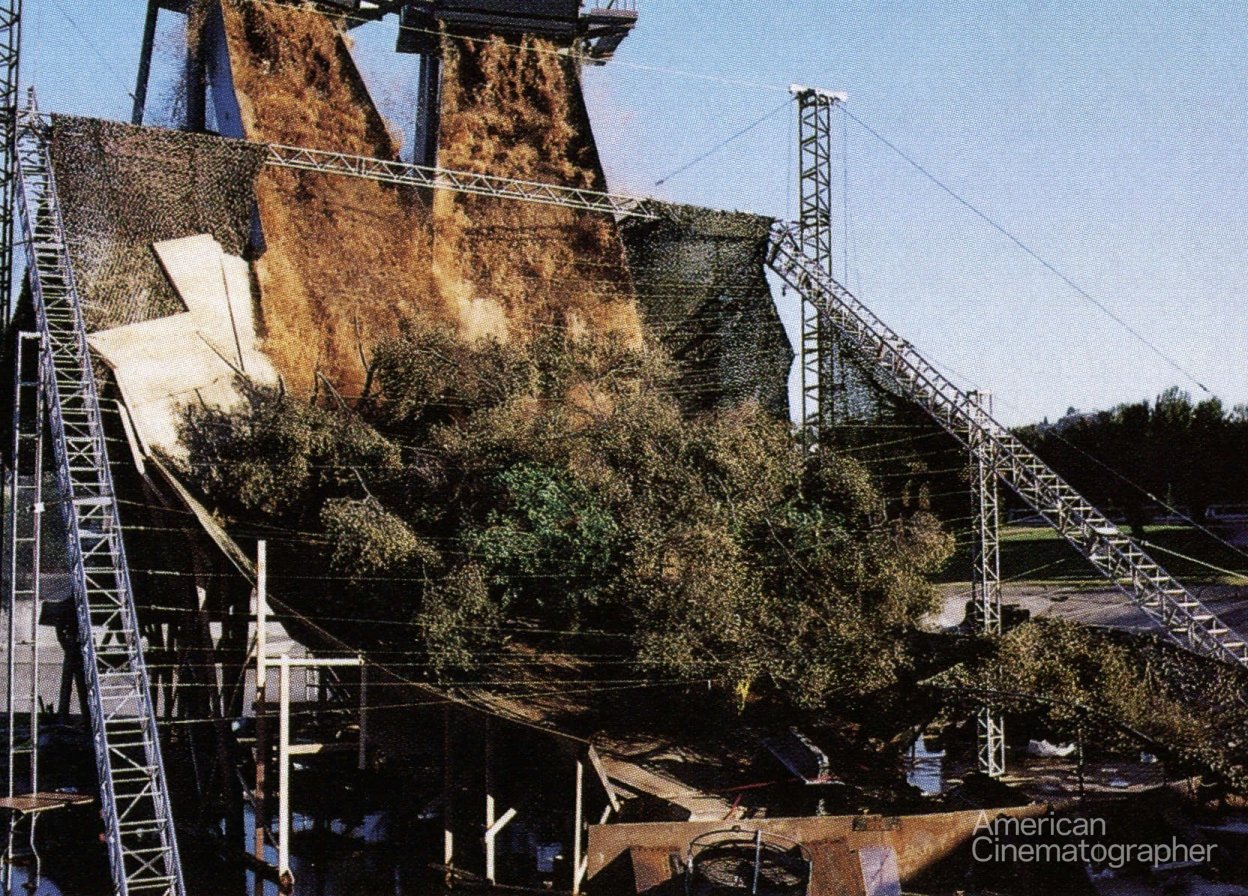

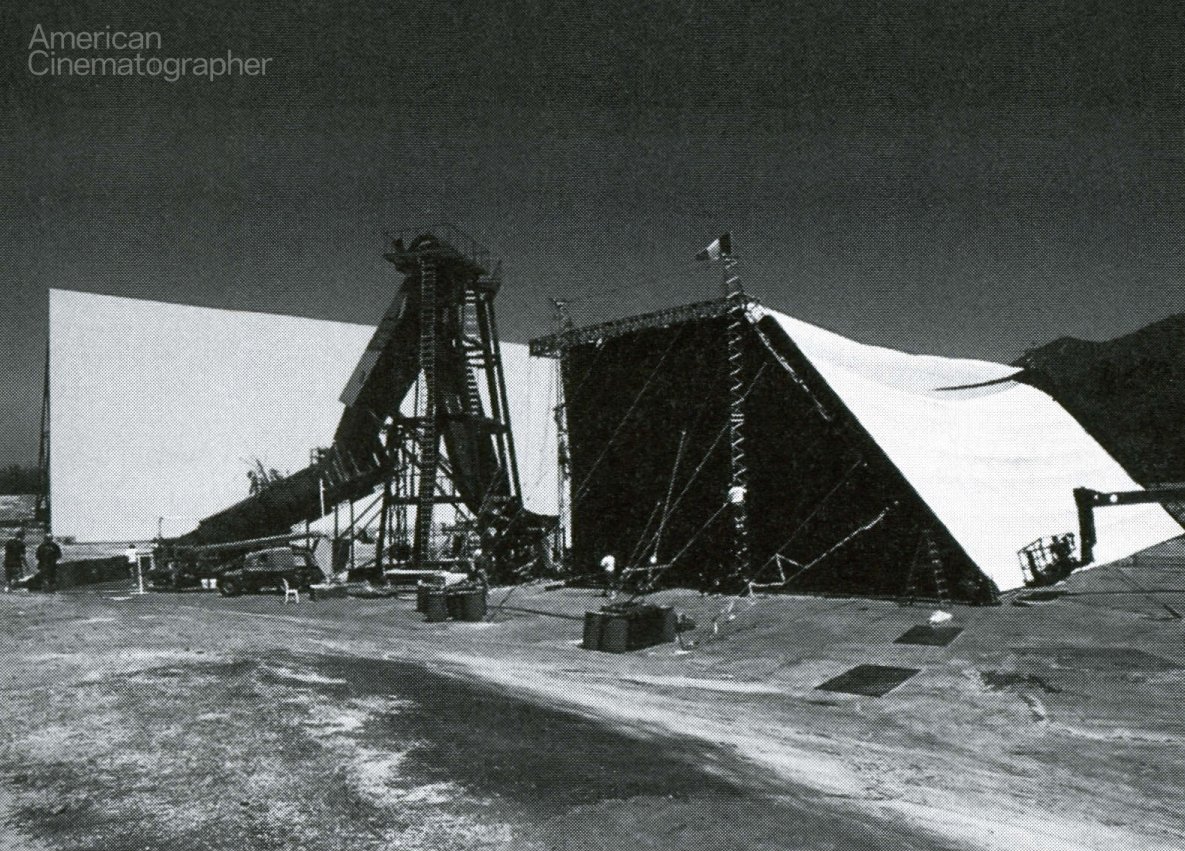

The Coens imagined using visual effects primarily to enhance a sequence here and there and to create a climactic flash-flood that saves the film’s protagonists from a triple-noose hanging. Nash acted as his own director of photography on the high-speed flood effect, which included a miniature cabin, trees and mountains in the background. Although DD’s modelmakers matched the live-action location built at Disney Ranch, the filmmakers ultimately preferred DD’s model to the real thing. “Originally, [cinematographer] Roger Deakins filmed a locked-off shot of the real cabin that they were going to show prior to the flood to establish the location, which we had to match,” Nash recalls. “We told the Coens that the match would never be 100 percent, but that our miniature would be of high enough quality that they could use it for the establishing shot. They were very skeptical.

“In creating the miniature, we performed a detailed survey of the location and used some proprietary photogrammetry tools,” Nash continues, “and I would say it was [an] 80-percent match. But when the Coens saw the model in the final take with the flood, they actually preferred it to their shot, and they wound up using the miniature for the establishing shot! Alan Faucher, George Stevens and their model crew did their usual amazing job.”

To believably re-create the interaction of real water with the set, DD’s miniature was built at V4 scale on a 30-degree angle to keep the water moving toward the camera, which was tilted up at the same angle so the set would appear level. Special effects supervisor Peter Chesney provided a pair of huge dump-tanks set up on twin 60' towers. On cue, the tanks released their 8,000-gallon payload, which completely flooded the 30'-wide x 60'-deep set and washed away the cabin, which was rigged with anchor wires from within to make it break up when it was hit by raging water. “The biggest struggle we had was getting the model to break into enough small pieces so that audiences would believe our heroes would survive,” Nash admits. “We did three takes, and the third one was the best, but a piece of roof came right up to the camera and stuck on the protective glass! We had to do a bit of compositing work, cutting and pasting water to break it up so that the roof would look as if it got consumed by water as the camera was hit by the wave.”

Nash set up two high-speed cameras running at 96 and 120 fps, respectively, to properly convey the scale of the flood as it engulfed the miniature landscape. “We were on the ragged edge because we were over-cranking and needed a ton of depth of field from the foreground leaves to the deep background,” Nash recalls. “We were outside in broad daylight, so we couldn’t add any more light. When we settled on the appropriate frame rates, the aperture was just barely holding enough depth of field. Roger [Deakins] shot the surrounding footage on Kodak EXR 5293, but we had to shoot on faster stock with out an 85 filter and then compensate digitally. That was a tightrope walk.”

Following a traveling, over-the-lip-of-the-wave shot looking down on our heroes, our POV is submerged along with George Clooney, who is shown in an over-the-shoulder shot as the wave slams into him. The underwater sequence was envisioned as and appears to be one continuous lyrical ballet. In actuality, it involved a painstaking compositing job with dozens of elements. “A banjo, a tire swing, picture frames, a gramophone horn and Clooney, as well as lots and lots of hair-pomade tins, were all shot underwater in Universal’s tank,” Nash remembers. “Our animation team created a CG bloodhound, which was fun, and we added some digital pomade cans that we could put in specific places and choreograph precisely alongside the film elements of floating cans. The Coens wanted [the audience to] first see one can, then a couple more, with the volume of cans building and building until we get above the surface, where they’re all popping up out of the water.

“The real challenge for us was taking these varied underwater elements, which were all shot handheld and varied greatly in water color and value, and blend them with each other as well as with digital elements into one long, lyrical shot,” Nash says. “Our compositing team of Claas Henke and Mark Larranaga did a beautiful job.”

When Clooney, John Turturro and Tim Blake Nelson surface, DD was able to aid the key transition from underwater by reframing the shot to keep the horizon out of frame while the cans bobbed to the surface. “The sequence was shot in Super 35, so we had the extra image area to actually reframe the above-water shot as Clooney popped up,” Nash states. “It looks as if the shot was operated that way, when in fact it was locked-off.”

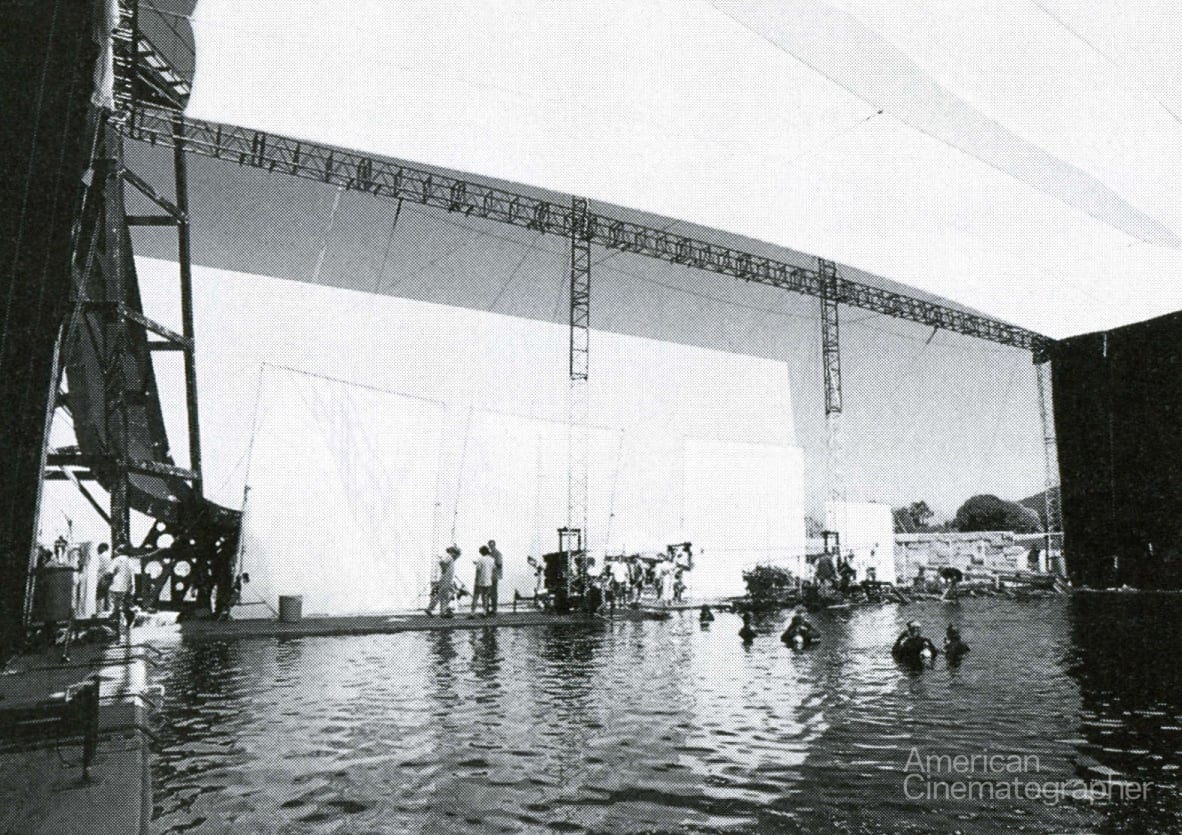

But the toughest challenge lay ahead: The actors were shot floating on a coffin in Universal’s tank, engaging in dialogue that lasts at least a minute, and everything seen behind them — the water, houses, and even a cow on a rooftop — was entirely CG. “Because he was shooting on water and had to light the scene to be overcast, Roger Deakins used the biggest silk I’ve ever seen,” Nash says. “It was like a roof that measured 120 feet across and 80 feet front to back, and it sloped right down to the waterline in the tank. The real water only extended behind them about 40 feet, and everything beyond that was digital, including the buildings and trees. The 3-D team, headed by David Prescott, fabricated all of the background elements and created the CG water, which had to blend seamlessly with the real water in the plate. We couldn’t use blue- or greenscreen because it would have reflected in the water.

“The camera was down at the actors’ eye level; their heads crossed over the silk and needed to be rotoscoped in order to matte them over the CG background. In long shots like that, [the matte edge] just begs to show off some chattering and little crawlies. An incredible amount of rotoscoping was done, but you’d never know it thanks to our paint and compositing teams.”

Nash says he enjoyed paying attention to the nuances that make the Coens’ films so much fun to watch. “O Brother is a little movie, but it was a great experience because they are such a pleasure to work with,” he concludes. “They’ve got the entire film in their heads before they show up for the first day of shooting. They know exactly what they want. They’re very reasonable and pleasant, their sets are very laid-back, and they do fabulous work. If I didn’t have to work with any other filmmakers for the rest of my career, I would be very satisfied just to work with the Coens.”

Unit photography by Melinda Sue Gordon.