Speed Racer: A Need for Speed

Speed Racer, shot by David Tattersall, BSC, translates a popular animated series into a live-action feature, calling for some unusual visual techniques.

In 1967, Tatsuo Yoshida's pioneering animated character, Mifune Go, was renamed Speed Racer and brought to American television. There, his exploits behind the wheel of the Mach 5 became every bit as legendary as they were in Japan. Now, directors Lana and Lilly Wachowski have taken Speed Racer to the big screen, breaking new ground in visual effects to move the character into the live-action world.

The film centers on young Speed (Emile Hirsch) and his attempts to save the family racing business, which is led by his father (John Goodman). After Speed turns down a lucrative offer from a competitor, Royalton Industries, Royalton (Roger Allman) vows that Speed and his Mach 5 will never cross another finish line. With the support of his family and his girlfriend, Trixie (Christina Ricci), Speed decides to beat Royalton at his own game by winning a death defying cross-country rally known as The Crucible.

Filming in Techno Color

For director of photography David Tattersall, BSC, the decision to join the Speed Racer team was easy. “When [producer] Grant Hill called me about the project, I said I’d sell my own grandmother to work with the Wachowski sisters,” he recalls wryly. Tattersall’s credits include high-profile digital features such as Star Wars: Episode II (AC Sept. ‘01) and III and numerous celluloid projects, including Die Another Day (AC Nov. ‘02), The Green Mile (AC Jan. ‘00) and Con Air (AC June ‘97), and he notes that the format for Speed Racer had not been determined when he came aboard the project.

“One of the first questions that arose was whether to shoot on film or digitally,” he recalls. “To bring the anime world to life, the Wachowskis wanted something very different — not really a film look, a digital look or even an animated look, but a hybrid of the three. Our goal was a kind of hyper-real look.”

Defining that look began last spring, when the filmmakers spent a week on stage shooting comparison tests with a 35mm camera and a number of high-end high-definition video cameras, including a prototype Sony CineAlta F23 that had just been unveiled. Tattersall recalls, “As we were testing, we talked about what the hyper-real look would be and discussed using superdeep focus and a smooth, grain-free ‘Techno Color’ palette, a kind of exaggerated digital version of Technicolor. Those [qualities] tested out to be more easily achievable with HD than with film.”

The F23 seemed uniquely suited to achieving the desired extreme-deep-focus look; the camera’s 2/3” CCDs could capture more depth of field than a larger single 35mm-sized chip. Also, Tattersall found the Sony camera to be “very user-friendly with its improved, more rugged and ergonomic design features, and a good choice for the Speed Racer shooting style,” he says.

When the team decided to go with the F23, technical adviser Vince Pace of Pace Technologies “moved mountains to make the first five camera bodies off Sony's production line available for us to use in Berlin,” adds Tattersall. “With the help of [technical consultant] Fred Myers, Vince also custom-tweaked settings and internal components to suit our particular needs.”

In keeping with the look of Japanese animation, the Wachowskis wanted certain sequences to have an infinite depth of field. However, Tattersall notes, “Shooting at extremely deep stops can be tricky; the amount of tungsten light needed to maintain a T5.6 stop for high-key sequences on large stages can get uncomfortably hot for everyone. I tried to keep the kilowatt count down and hovered around T4 or less on medium-wide Zeiss Digiprimes for most of the shoot. When we weren’t throwing a zoom or looking for extreme compression or a bendy distortion effect, Lana and Lilly would invariably land on one of two focal lengths, the 14mm or the 20mm.” (These focal lengths are equivalent to 35mm lenses of 35mm and 50mm, respectively.)

More on Racing Cinematography:

Jacques Jouffret, ASC Shoots Gran Turismo

Second-Unit and Helicopter Camera Operator John Stephens Recounts the Making of Grand Prix

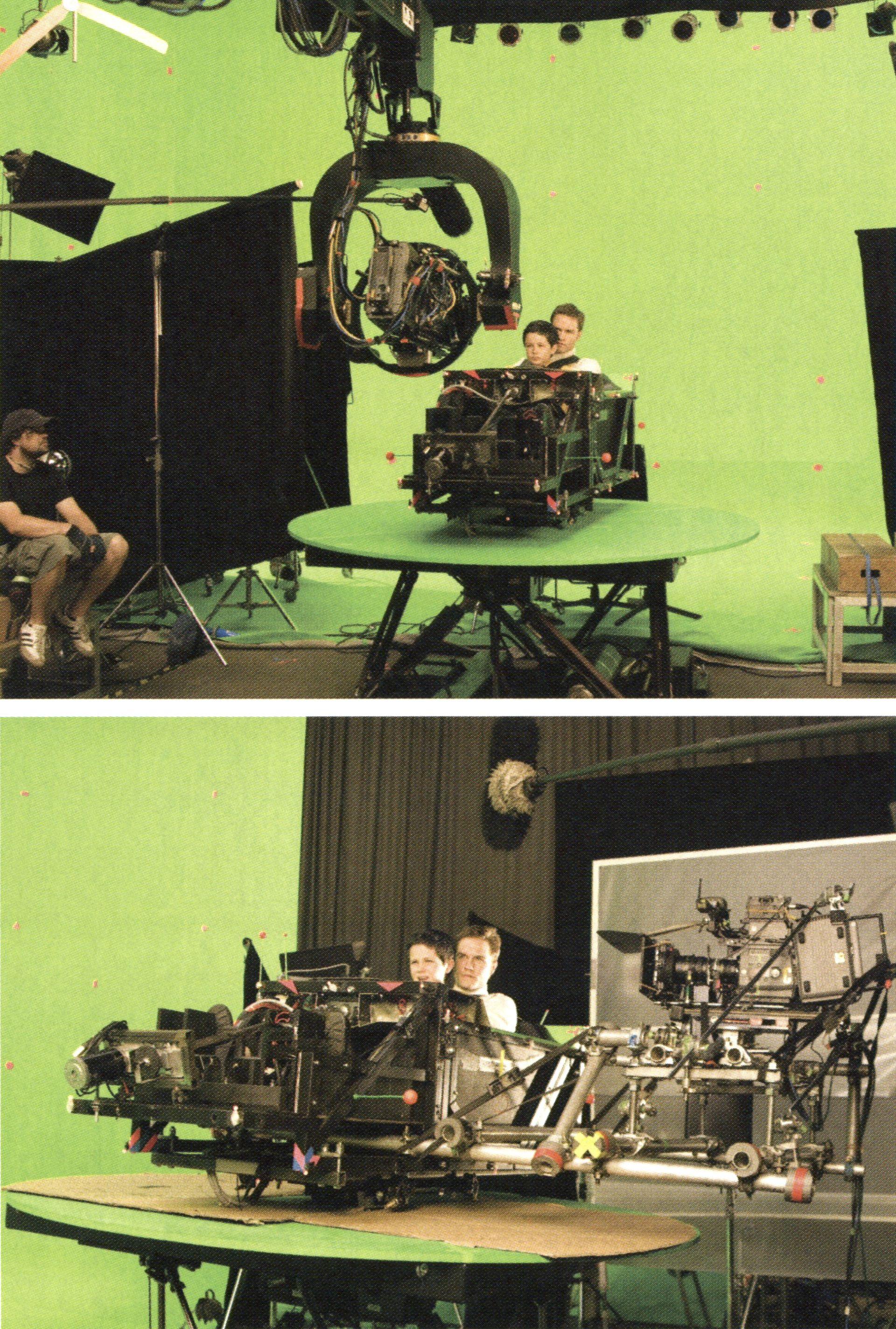

What enabled the filmmakers to achieve extreme depth of field was a method visual-effects co-supervisor John Gaeta (The Matrix, Matrix Reloaded, Matrix Revolutions) dubbed “photo anime.” Separate foreground, mid-ground and background elements were shot, all in sharp focus, and then composited to create an image with a depth of field well beyond normal optical limits.

“When we looked closely at Japanese animation, we noticed that a lot of it is done with a large painted background and modified layers on top of that, like traditional cel animation,” says Gaeta. “It puts everything in focus.”

Not everything in Speed Racer looks that way, however. Visual effects co-supervisor Dan Glass (V for Vendetta) explains, “We learned quickly that if you present the whole film in super-deep focus, people don’t know what to look at; you lose the traditional filmmaking language of utilizing focus to direct the audience’s eye. So some sequences were shot with more traditional optical qualities with regard to depth of field, and in other sequences we went to the other extreme, putting the background element so out of focus it almost became abstract.”

As their work evolved, the filmmakers began using photo anime to create an unrealistic-looking anime-style perspective as well. Tattersall explains, “We started experimenting with the idea of mismatching our foreground, midground and background lens sizes and focus planes. For example, we might use a medium-wide lens for the foreground and a super-long lens for the background. We called this ‘faux lensing,’ where we were literally inventing optical properties that aren’t physically possible.”

The team also experimented with altering other physical optical characteristics, including the bokeh, or the way that out-of-focus areas are rendered within the image; this corresponds to the shape of the iris. For instance, when Speed falls in love with Trixie, the effects crew transformed the “faux lens” iris shape into a heart, creating heart-shaped out-of-focus highlights in the background. “We experimented with the out-of-focus-areas idea during our previz, and it was advanced much further by Daren Poe of Digital Domain and Jake Morrison, who spearheaded the in-house team that handled 300-400 photo anime shots,” says Gaeta.

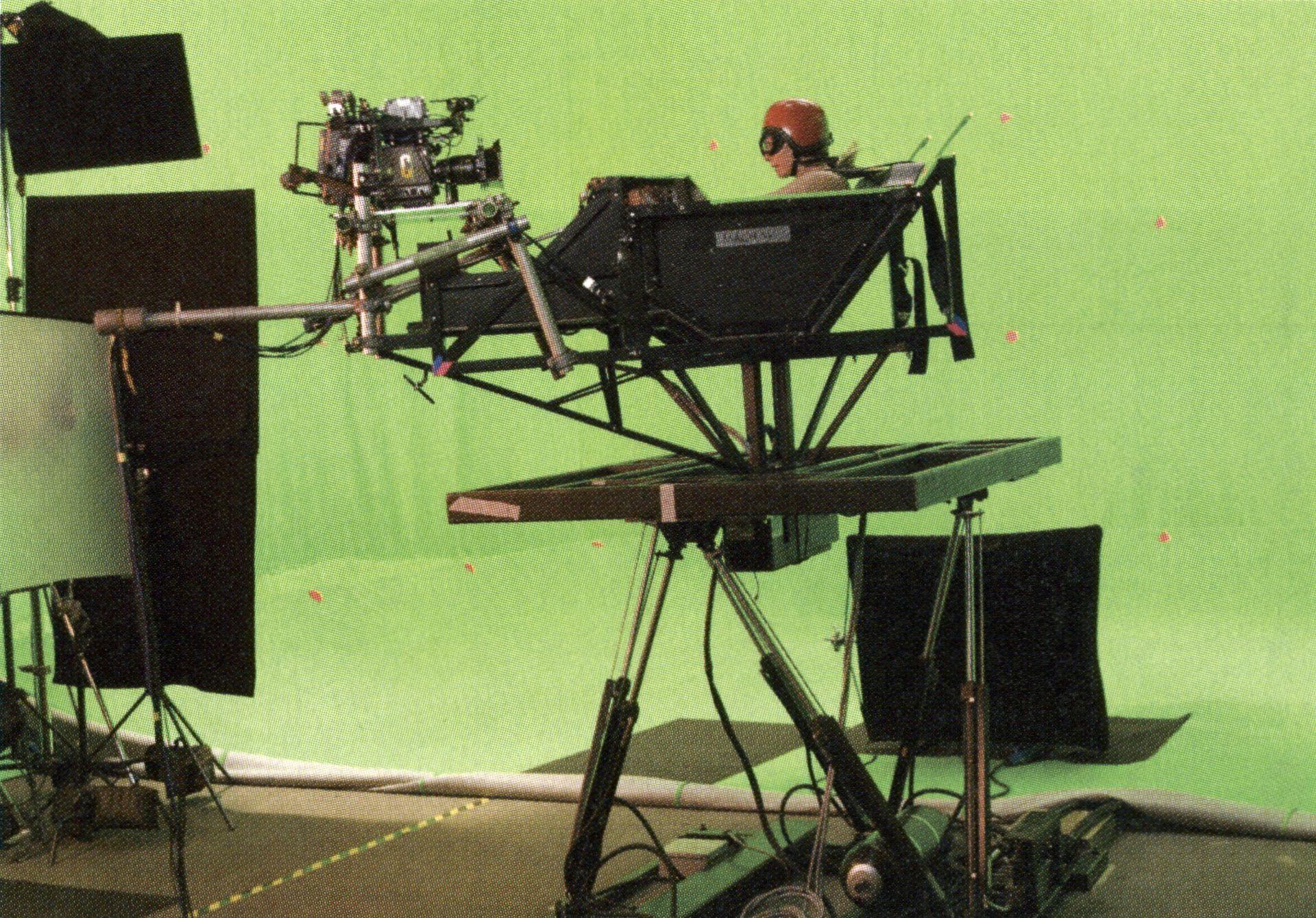

The extensive compositing Speed Racer required translated into a lot of time in front of greenscreens, and one tool Tattersall employed for such work was a special greenscreen box: a rigid 6’-square, 10”-deep rig fronted with chromakey green material and backlit with tungsten Kino Flo tubes. Each side featured a large handle, enabling grips to carry the box behind an actor and immediately turn any medium or close shot into a greenscreen setup. “If the shot was any wider than a cowboy, we’d either move to a greenscreen stage or walk outside, where we had green already set up, but the greenscreen box made it very easy to reshoot a moment for a composite element without having to carefully light a greenscreen or move the actors from the set,” says Tattersall.

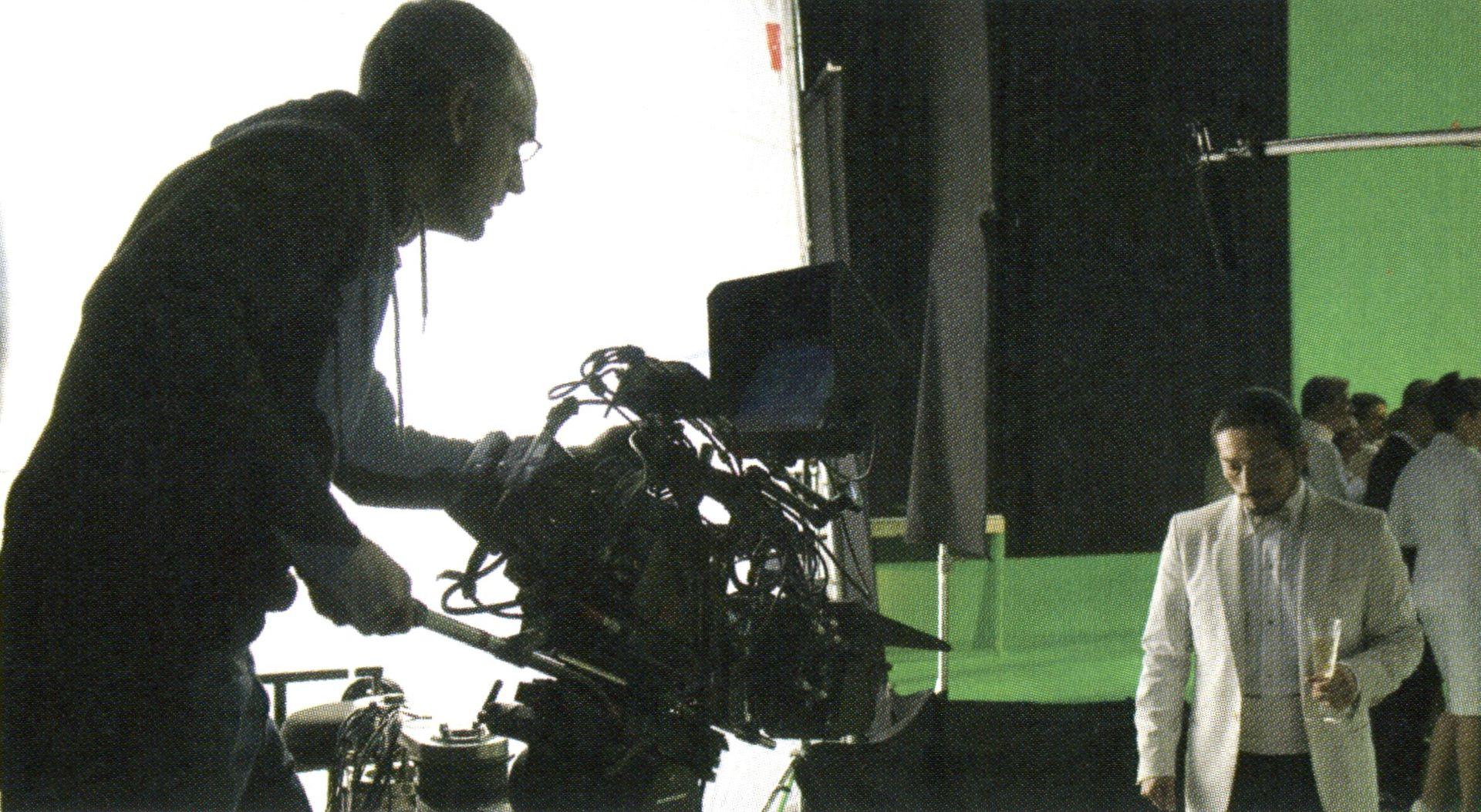

Two units, often three, were running throughout the lean 60-day shoot, which took place entirely onstage at Studio Babelsberg in Berlin. “The production company struck a deal that gave them incredible tax incentives if we completed work by a certain date, so our schedule was fairly tight,” says Tattersall. “We were definitely shooting fast!”

Working in a Bubble

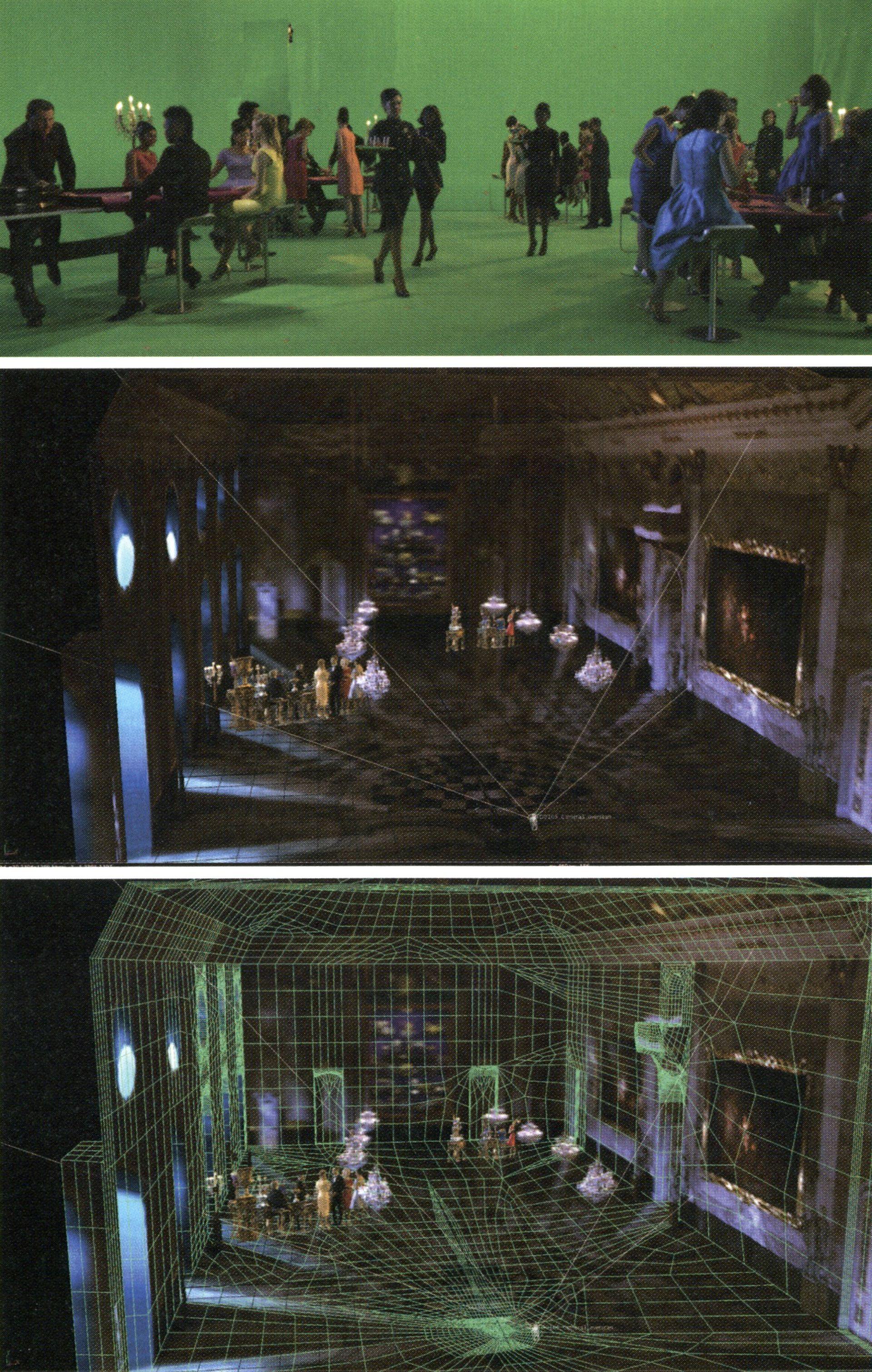

The second unit, led by director James McTeigue and cinematographer Harvey Harrison, BSC, focused primarily on the racing sequences. Another unit, known as both the “world unit” and the “bubble unit,” set to work before principal photography began. Led by Dennis Martin, this unit traveled the globe in search of exotic, beautiful locations, armed only with high-end Canon EOS SD and EOS 1D Mark II digital still cameras and a nodal tripod head; they used this equipment to capture high-resolution stills that Martin later stitched together to create a 360-degree two-dimensional background, or “bubble.” Glass, who supervised the integration of the bubbles into the film, explains, "We simply couldn't afford to build the incredibly complex and detailed environments the bubble unit shot, either as set pieces or as completely virtual sets.

“Using still images as virtual backgrounds has been done for many years now,” continues Glass. “For Speed Racer, we were using very flat perspectives and moving our virtual camera within those flat perspectives to simulate camera moves, but we were doing it so the parallax didn’t quite work right. It’s supposed to feel artificial and contrived.”

Each bubble comprises hundreds of high-resolution digital stills, and each element was photographed up to seven times at bracketed exposures — from three stops under to three stops over — to create super-high dynamic-range images that captured every detail of the locations. (Most bubbles ended up being about 12,000 pixels wide in resolution, and some were twice that size and larger if more detail was needed.)

Matte painter Lubo Hristov used digital tools to “paint” over the stitched bubbles, accentuating some elements. “Lubo took the existing natural details, colors and textures, and exaggerated them in very striking and unique ways that lend extraordinary richness to every bubble,” says Glass.

One of the film’s locations, the Drivers’ Club, took the bubble unit to a perfectly preserved castle just outside Berlin. Public access was limited, and Martin and an assistant entered the castle with only a still camera and a tripod; standing in the middle of a room, they took their photos without disturbing any of the centuries-old structure.

“In post, we took that amazing environment and filled it with 60 actors,” says Gaeta. “We would never have been able to bring that many people into that room, let alone cameras, lighting and everything else that comes with a movie production.”

Because the bubble unit finished most of its work before principal photography began, Tattersall and the Wachowskis could preview the environments and rough composites while they were shooting on the greenscreen stage. Using Sparky, a proprietary system designed by Digital Domain, they could see real-time rough composites of the actors in the bubbles, enabling them to match interactive lighting and camera moves.

A Candy-Coated World

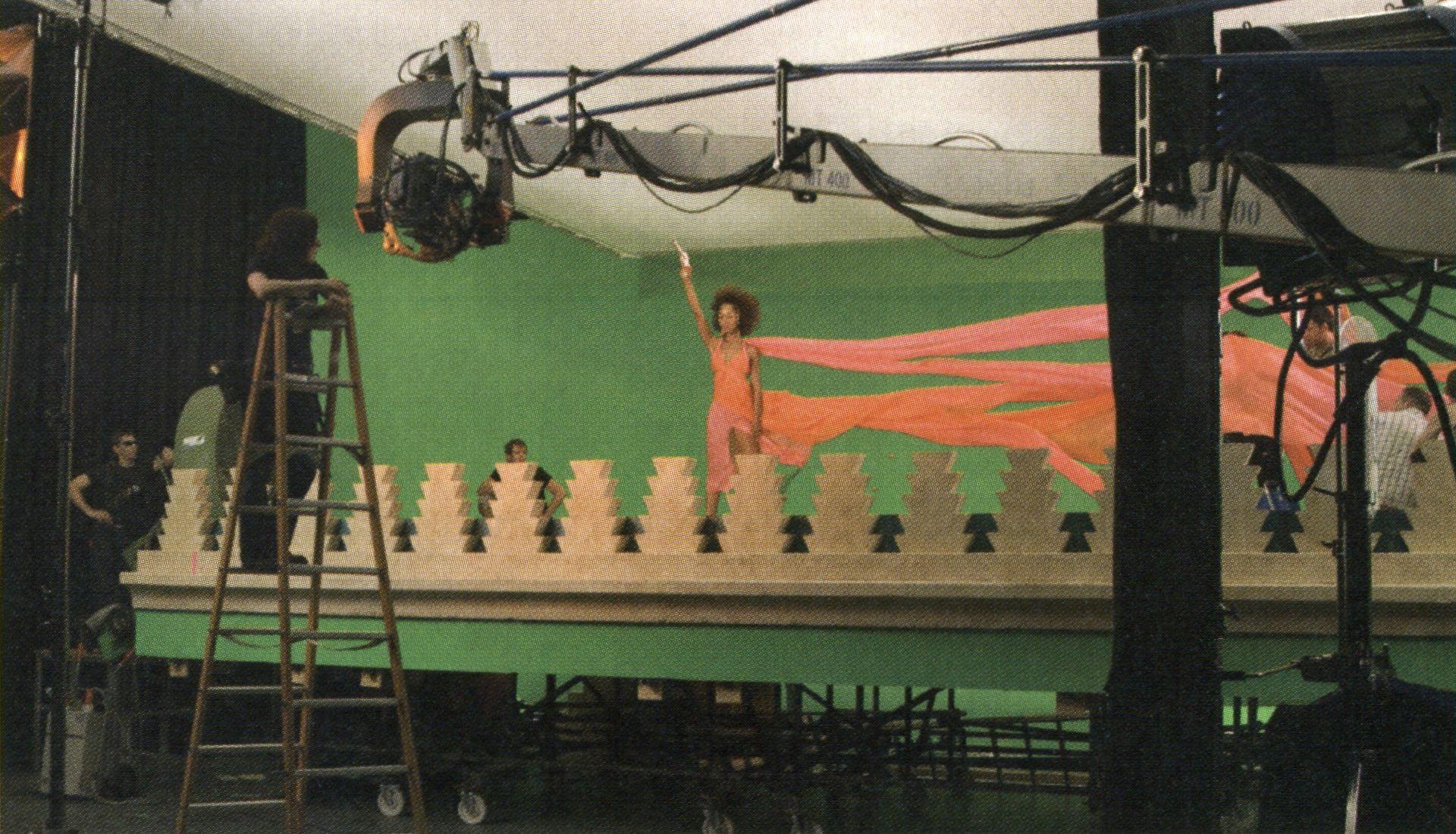

Most audiences associate the Wachowskis with the brooding style of the Matrix trilogy (AC April ‘99, June ‘03, Nov. ‘03), but Speed Racer takes a sharp turn into a candy-coated world. “Speed Racer is lightweight, bright and funny, with outrageous contact-rally sequences and monkey kung-fu,” says Tattersall. “It’s quite the polar opposite of the Matrix films. It’s very, very colorful; the sets and costumes feature unusually bright colors, and I was often gelling the lights with deep Congo Blues or fuchsias or Chrome Yellow. Once the photography was done, we passed the baton to the visual effects artists, and they used digital filters and gamma-warping to heighten and exaggerate the colors even more.”

Glass notes that Speed Racer’s hyper-saturated color palette “was another significant motivator to go with an all-digital pipeline.” He continues, “One of the important benefits of the F23 was its considerable dynamic color range. We learned our lesson on other HD projects, where we ran into all sorts of color space problems in the post pipeline. Most HD cameras have their own proprietary color handling, and that can complicate how well that camera’s color space integrates with post systems. We wanted to make that as [simple] as possible, so we converted the F23’s natural 12-bit linear color space to the Kodak Cineon 10-bit Log standard before handing it off to any of our post facilities. There's no loss or compromise going from 12-bit linear to 10-bit Log, and it allowed everyone to work from the same standard.

“In addition, we sent [all of the effects facilities] a custom lookup table [LUT] that we cooked up with Digital Domain and Pacific Title [which handled the digital intermediate and some effects shots] to emulate the color saturation we had in mind,” continues Glass. “That got everyone very close to a final look, but we built in some headroom so no one could push the saturation too far and break it.”

Tattersall notes that when shooting digitally, he normally uses hi-def monitors to adjust his lighting. However, on Speed Racer, he was operating the A camera, so he was often away from the monitor tent. “On the last two Star Wars movies and Next [2007], I spent most of my time at the monitor with my engineer and communicated remotely to my gaffer and crew,” he recalls. “On Speed Racer, I was on the floor operating and communicating directly with my crew, the directors and the actors, and that helped us move more quickly. The cameras were set up every morning to gray scales, and we didn’t really tamper with settings during the day. I would go into the engineering tent to check the settings after the first take of every new scene, just to make sure everything was okay, and then I’d spend the rest of my time on the set with the camera.

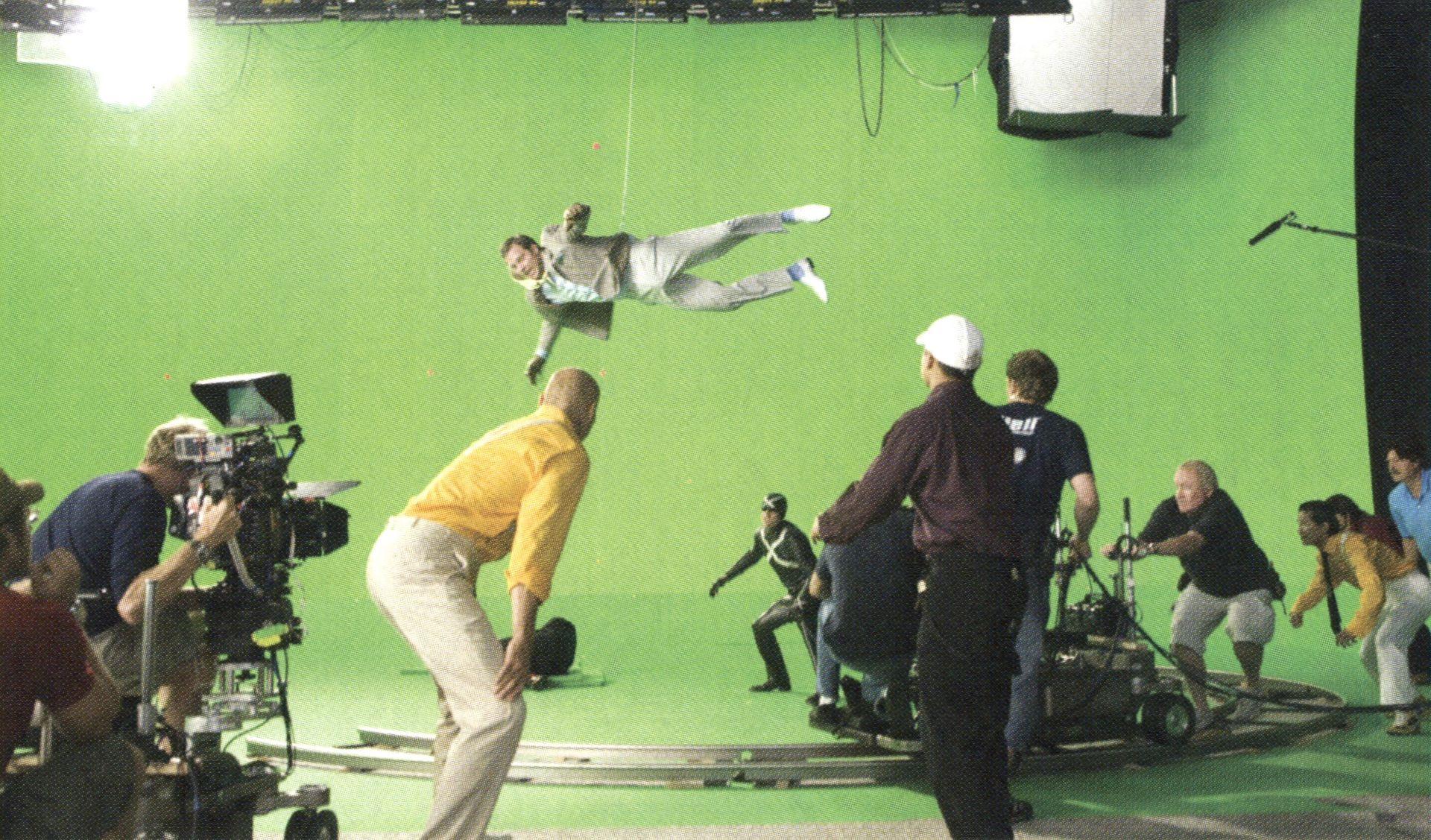

“It’s a very kinetic show from a camera point of view,” he continues. “Lana and Lilly were constantly asking me to do whip-pans, crash zooms and trombone tracks. They had me chasing kung-fu stars and machine-gun tracers, flying stunties and crashing ice sculptures. Frankly, it was just a lot of fun.”

Tattersall rarely adjusted the F23’s internal matrices and menus, and he captured most of the action at a -3db gain setting to achieve a sharp, noise-free look. The camera captures 4:4:4 1920 x 1080, but he occasionally pushed it to 4:2:2 to capture 60-fps slow motion. When the filmmakers needed faster speeds, they brought in Vision Research Phantom and V1O high-speed cameras (which captured 4:2:2 direct to data up to 1000 fps) and an NAC Hi Motion camera (which captured 4:2:2 direct to data up to 600 fps).

With a young audience in mind, the Wachowskis set a target running time of 100 minutes, but their screenplay clocked in at a whopping 160 pages. To help them compress time and shoot the entire script, “we shot a lot of the dialogue at 23 fps, and layered backgrounds from adjacent scenes sometimes slide back and forth under the foreground actors [to achieve quick transitions],” says Tattersall. “There’s a bit of an animated feel to those sequences, and it’s not subtle. The whole film is very fast-moving.

“The Wachowski sisters are pioneers and artists — the real thing — and I was really impressed by their way of working,” he adds. “They’re not at all interested in what’s in fashion cinematography-wise; they’re not copycats.”

Crossing the Finish Line

Although the filmmakers initially planned to record to the F23’s dockable HDCam SR deck, they adopted the Codex system for direct digital recording before production began, and soon, the Codex became the primary record source and the HDCam SR became the backup. “The Codex system is fantastic,” says Tattersall. “It was really very handy, because it makes it possible to play back full-resolution HD instantaneously. You’re not watching some proxy or an NTSC down-rez; you’re looking at the full image. And throughout the day, the Codex drives could be sent directly up to editorial, and the footage was immediately ready for them.

“Michael Taylor, our HD engineer, would capture stills [off the Codex] while we were shooting, and I would then go through them and pick the selects,” continues the cinematographer. “That gave us a sizable library of images we could use to communicate with the post facilities, editors, second unit and continuity, and I took them home to color-correct them in Photoshop for later reference in timing. I found it enormously helpful for color matching and lighting matching when setting up reverses or coming back to the same scene another day; we were able to put the still up on the monitor and wipe from it to [the feed from the camera], and we could match the two perfectly. That reduced our time spent grading at Pacific Title quite a bit. Also, because the images are full resolution, even the publicity department can use them.”

In addition to playing back full-resolution HD, the Codex system is able to flavor HD files in any format desired. For Speed Racer, the files were converted to MXF for Avid, and the editors were handed ready media on drives with no capture time necessary. The sound department downloaded its masters into the Codex system, and those were likewise delivered ready to the editorial department. Instead of just watching dailies in the morning, the crew was able to see rough-cut and rough-composited sequences.

With each foray into digital cinematography, Tattersall strives to improve the workflow, and on Speed Racer, he felt it was time to address an issue that had long been on his mind. He explains, “All video monitors are natively daylight-balanced, and that’s fine when you’re in a mixed-lighting situation or working with daylight-balanced fixtures, but when you're working in all-tungsten light, the monitors never look quite right compared to what you see on the set. On several occasions, I’ve wanted to balance the monitors to a tungsten color temperature to get rid of this disparity. Dan Glass and Pacific Title worked out a special LUT for our monitors that emulated a 3200°K balance; it wasn’t perfect, but it was much closer to what I wanted. Of course, we had a tented engineering station on set that was calibrated correctly, but we also had various monitors all over the place, including two SO-inch plasma screens for the Wachowskis. Balancing those to tungsten got the image much closer to what we were seeing with our eyes.”

When it came to lighting Speed Racer, “it was fluorescents and LEDs for the most part, and both are great ways to reduce heat and power consumption,” says Tattersall. “We used a lot of 8-foot Kino Flos and the new LitePanels 12-inch LED systems, which seemed to be appropriate for the HD look. I also used the 19-inch Ring Light, which was great; Lilly and Lana called it ‘Vogue cover lighting.’ The 8-foot Kinos are versatile, they go up quickly, and we could easily bank them together in long lines or double and triple them up. They’re lightweight and cool, which was important with the amount of light we were working with. They make even enclosed sets more comfortable. There were times when we turned to Maxi-Brutes, but we didn’t do it often.”

Pondering the advancements in the digital-to-film workflow that he has witnessed firsthand, Tattersall says, “Without a doubt, the future of production is moving to HD. It’s kind of the obvious way to go. Most departments have seen the advantages of digital and moved in that direction. Production is one of the last departments to become completely digital, but it’s inevitable that it will; the potential advantages are too great to ignore.

“For Speed Racer and similar effects-heavy shows, the principal photography secures the foundation of the image, and then the image is further developed and refined in post,” he continues. “Both John Gaeta and Dan Glass made incredible contributions to the image and the cinematographic elements of Speed Racer. They took our foundation and evolved it into what the movie eventually became. It’s not just a cinematic movie, but a cinematic/post mix, and staying in a digital medium from beginning to end made the whole workflow much more efficient.”

Tech Specs

2.40:1

High-Definition Video

Sony CineAlta F23; NAC Hi Motion; Vision Research Phantom, V10 cameras

Zeiss Digiprime lenses

Digital Intermediate

Printed on Kodak Vision 2383

Unit photography by David Appleby. Still images via ShotDeck.

For full access to the American Cinematographer archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.