After Yang: A Robotic Future Steeped in Nature’s Beauty

In this poetic sci-fi feature, cinematographer Benjamin Loeb and director Kogonada envision a world inhabited by androids, stricken by grief, but always teeming with life.

When cinematographer Benjamin Loeb, FNF saw Kogonada’s 2017 feature debut, Columbus, he felt an immediate connection to the director’s work. “There are certain films you watch and say, ‘I wish I’d made that movie,’ and I had that feeling watching Columbus,” Loeb recalls. At the time, he didn’t know how — or if — they’d ever work together, but he says that even then, “I just knew that my sensibilities would align with whatever led him to make that movie.”

Two years later, Loeb would begin principal photography on After Yang — Kogonada’s sophomore feature, a ruminative sci-fi drama set in some near-to-distant future.

Of all the candidates Kogonada considered for the job, Loeb was the last to get an interview, and he laughs as he remembers how “very early in the conversation, he mentioned that there were others with more experience.” But while their first few phone calls barely covered the project itself, they revealed enough about the pair’s shared tastes to seal the deal.

“It was really a marriage of sensibilities,” says Kogonada. “There’s something in the air about Benjamin’s cinematography — that thing that’s always invisible to us, which is space itself. He really values negative space, and he infuses it with something that feels palatable and tangible.”

“A lot of what Kogonada appreciated in what he saw from me revolved around this idea of not being afraid to let things be left absent within the frame,” Loeb explains. “Maybe darkness could conceal an emotion. Maybe you wouldn’t see a face at all. Maybe you wouldn’t even see a character in a frame, and the scene is left to audio. The absence of whatever information you’re concealing engages the audience in a way where, all of a sudden, you’re participating intellectually. You’re not just looking at something — you’re having to use your imagination in a different way.”

Before he became a feature filmmaker, Kogonada made his mark as a prolific video essayist, and it was through that work that he first showcased his scholarly devotion to the films of Yasujirō Ozu. The famed Japanese director’s influence is ever-present in After Yang, but it’s perhaps felt most in its framing — in how people and places exist within a space.

“In Ozu’s films, he wouldn’t be afraid of leaving emotional moments to a wide shot, or letting emotional qualities come though body posture,” Loeb explains. “So, something that became as important as the idea of ‘absence’ was the approach of framing shots wide while still keeping their emotionality.”

This philosophy guides Loeb’s shot choices as soon as After Yang begins.

The film leads off with a wide shot of Jake Fleming, (Colin Farrell), his wife Kyra (Jodie Smith-Turner), and their adopted daughter Mika (Male Emma Tjandrawidjaja), who stand shoulder-to-shoulder in a grassy field, ensconced in the lush greens of windblown trees and sunlit weeds. As they call out to the fourth member of their family, Yang (Justin H. Min) — who stands just out of the frame, setting up a camera for a group photo — their gestures suggest there’s some subtle distance between them.

Yang, we soon learn, is a “technosapien.” A lifelike android animated by artificial intelligence, he was purchased by the Flemings to serve as both a big brother to Mika and a cultural link to her Chinese ancestry. The family fully embraces him as one of their own, but when his body suddenly shuts down, they’re thrust into a period of intense mourning.

The final, vibrant moments of Yang’s life, and the odd abruptness of his death, are juxtaposed in the opening credits sequence. In a series of static wides, the Fleming family competes against groups from around the world in an online dance competition. Again, it’s their bodies, not their words, that tell the story: They move in perfect harmony, until the music stops and Yang malfunctions and flops to the floor, throwing Jake, Kyra, and Mika into disarray.

“That sequence was discussed at quite some length,” Loeb says. “It’s so early in the story and it has a certain type of energy that doesn’t really exist in the rest of the film, which makes for a nice contrast.”

“Since so much of the film is about the dissolution of this family, I loved the idea of a credits sequence that would first introduce the family as being in sync,” Kogonada says. The director envisioned the sequence as an homage to the opening of the 1979 Shaw Brothers kung fu classic Kid with the Golden Arm, with its bold visual style and rhythmic cadence.

“Kogonada showed me that film as reference, and it had these fighters doing different types of martial arts against colored backgrounds,” Loeb says. “It felt so graphic and simple, and it became an inspiration.”

To achieve this look, the crew decided to shoot the whole sequence at 1896 Studios & Stages in Brooklyn, New York. Loeb, gaffer Andrew Hubbard, and key grip Ethan June used multiple Arri S60 SkyPanels, rigged to existing aluminum beams, and utilized these through a skirted 12'x12' full grid below it to soften the light. As a frontal source, they also used additional S60s through an 8'x8' full grid frame.

At first, they wanted to shoot the actors against various colored fabrics, to capture the background effect entirely in-camera. But once they saw that the fabrics wouldn’t hang straight, they opted instead to shoot the choreographed dance against a 20'x20' bluescreen and color it in post.

For the last moment of the sequence, which jumps back to the Fleming house, the crew used a small 4'x4' aluminum LED frame, with foamcore on one side and depron on the other. Four Astera tubes lined on the inside, and a small hole was cut in the middle, allowing them to put the lens inside the light. (The crew also used this frame for each scene in the film that depicts a “screen call” — a futuristic video communique system that sees the characters speaking directly into the camera to one another.)

Once Yang shuts down, the euphoric spell of the dance sequence is broken, and as the Flemings come back down to Earth, so too is their world steeped in earthy tones. The film’s palette and production design foreground Kogonada’s vision of the future: A strange, yet serene era in which humans and their android counterparts are more organically entwined with nature than they’ve ever been.

“It’s a time where the world has gotten greener, and there’s been some kind of environmental event that’s changed the way people live,” Loeb says. “And the film is also very much about interiors, so we wanted nature to be present even inside the Fleming family’s house.”

Alongside Kogonada and production designer Alexandra Schaller, Loeb spent six weeks scouting locations. Their mission, he says, “was to find a home that would allow us to bring this idea of ‘outside in.’” Eventually, they found what they were looking for in an Eichler home on the outskirts of New York City — a rarity, as real estate developer Joseph Eichler built far fewer of his signature Mid-Century modern-style houses on the East Coast than he did across California.

“Not only did this space have windows all around and greenery outside, but we were also able to move a tree into the actual atrium of the house,” Loeb says. During prep, he shot multiple angles at different times of day throughout the house with an Alexa Mini (which was also his camera of choice during production). Although he didn’t work with storyboards, this approach allowed him to create photo boards, which helped him vary his angles and blocking of scenes in the space. Line producer Becky Glupczynski served as a stand-in:

“For the house, we had two fly swatters to block the sun, which also doubled as bounce sources when we needed them,” Loeb describes. “For all our bounce sources, we used HMIs to keep the reflected light a bit colder. For our key at the house, we utilized an Arri T24, but because of the sheer number of days and scenes to be shot in the Fleming house, we lined the sides with T12s and bigger HMI bounces so the moves became a bit quicker.”

At its heart, After Yang is about reflection — about characters whose quiet contemplation of life is triggered by immense loss. Loeb felt it only natural, then, to make characters’ reflections through window glass one of the film’s key motifs.

Among the finest examples of this flourish are the trips the Flemings take in their driverless car, where waves of light from a tunnel wash over the windshield, as if to crash down on the grief-stricken family.

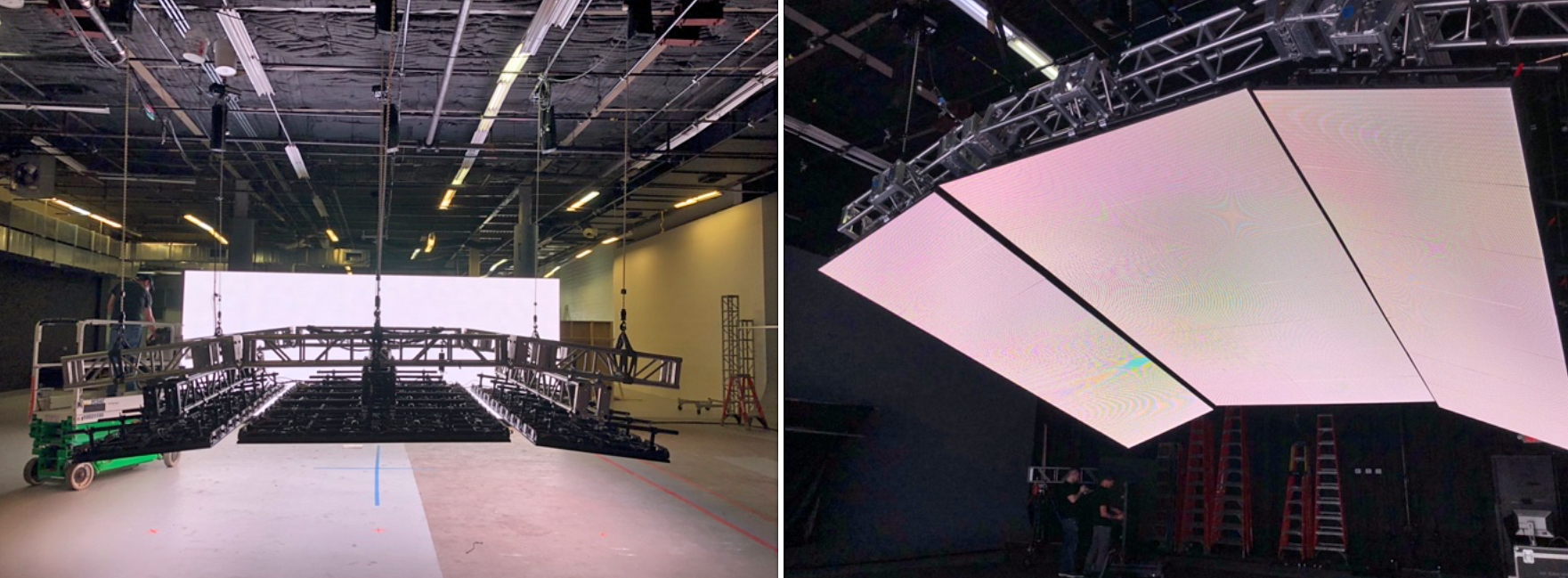

Loeb and Kogonada knew these shots would need to be done on a stage, but neither of them wanted to use a greenscreen. Instead, they enlisted the help of PRG, the Atlanta-based company that specializes in LED walls.

Key grip Chris Beattie rigged these shots, drawing from his experience rigging similar sequences on past projects. For the LED walls, the crew used Onyx 2.8mm tiles for the overhead section and one of the side walls. For the background LED wall, they used CB5 LED tiles. They collaborated with PRG and VER for the wall technology.

“Our VFX team [at Raynault VFX] built a landscape that we could project through from these walls, to get a clear, sharp reflection on the glass of the car windows,” Loeb says. The top 20'x20' wall strung up above the car “barely covered the windshield," he adds — which meant that it would need to be so close to the car that the lights’ diodes would be visible.

At first, Kogonada thought it best to soften the LED walls, to hide the pixels from audiences’ view. But Loeb persuaded the director to try it another way. “I made the case that if we diffuse those screens, the reflections we filmed would become too soft and feel disjointed from the material, and that didn’t fit the world we were building,” he recalls. “After some tests, we agreed to tweak the pixel density and make it a little less clear. When we played the footage back, we saw that the pixelation on the reflections merged with the textures of the car window glass, and we thought that was really interesting. So, we let the screen be naked and embraced those qualities.”

Another richly textured sequence delves deeper still into the spiritual link between humans and “technos.” When yearning to feel close to Yang in his absence, Jake puts on a pair of high-tech sunglasses, which transport him into a cosmos composed of Yang’s digitally catalogued memories.

During this dazzling display, After Yang expands from its mostly 2.35:1 widescreen aspect ratio to 16:9. Loeb filmed this sequence in Super 16 mode, with the camera to his shoulder, at an eye-level height close to Min’s that helped filter the scene through Yang’s perspective. Aiming to build the sequence from Yang's singular vision, he filmed with a vintage Canon 8-64mm zoom, taped off at around 25mm on the barrel.

While Yang’s memories were treated in this way, the main portion of the film, along with the human memories, were photographed with detuned Panavision Primo lenses. The “screen calls” were photographed in 4:3 with a Pathé 50mm lens.

“Kogonada and I are huge ramen fans,” Loeb laughs, “and we talked about wanting the film, like ramen broth, to exist in different layers. It isn't just a singular ingredient — it’s all of these little nuances that bring together the final taste the film should have.”

Shared love of layers aside, Kogonada’s favorite shot in After Yang is far less complex. “I love the shot of Mika and Yang at the very beginning of the film: They’re on the couch with the tree behind them, and she’s laying on him after he’s shut down. I love the colors, composition, and content of that shot, and how it gives you a sense of these characters who are family, yet not family.”

“Family, yet not family” could just as easily describe the on-set atmosphere that Loeb credits Kogonada with creating.

“Everybody was so deeply focused, involved, and had agency,” Loeb says. “Kogonada’s such an inquisitive person and he’s never afraid to ask you about your heritage, where you’re from, what your parents are like… I really respect his wanting to know the people we’re working with, in a way that isn’t just, ‘You’re the gaffer, you’re the key grip, these are your jobs.’ It’s more about, ‘Who are you as a person, and why are you here?’ And in many ways, that’s what After Yang is about.”

The picture premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and recently played at the Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film Prize. It is now playing in theaters and is available to stream on Showtime.

AC most recently covered Loeb’s work in the horror fantasy Mandy (2018).