Dying to Leave Earth: Mickey 17

Cinematographer Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC reteams with director Bong Joon Ho to launch a dystopian vision of immortality.

This article originally appeared in the April 2025 issue of AC.

The futuristic black comedy Mickey 17, shot by Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC and directed by Bong Joon Ho, presents a title character who is known as an “Expendable” — a human worker who performs extremely hazardous tasks in exchange for a guarantee that if he dies, he will immediately be resurrected in an identical, 3D-printed form with all memories intact.

When Mickey Barnes (Robert Pattinson) signs on to become an Expendable and help colonize a distant ice planet, things don’t quite go as planned: Soft-spoken Mickey 17, the protagonist’s 17th copy, is presumed dead, and a volatile Mickey 18 is printed prematurely. With the pair of Mickeys (both played by Pattinson) now considered “multiples” — a banned predicament — authorities call for the identical duo to be executed.

Khondji calls Mickey 17 “a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” noting that “it has all the trappings of a sci-fi movie, but beneath that, it’s a deeply moving story about humanity. It’s hard to say more without giving away too much, but the fact that Rob Pattinson plays two characters in the film is significant. That duality brings an incredible dynamic.”

The cinematographer recently connected with AC from Paris to discuss the project, his second collaboration with Bong, after Okja.

American Cinematographer: You’ve noted in the past that it’s important for you to find the rhythm of scene. How do you and Bong do that?

Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC: When we were in Seoul working on Okja, there was a shot we just couldn’t get. It had to do with the actors’ movements, their walking and talking, and how it coordinated with the camera. Something was out of sync. That’s when we realized rhythm is in everything, even in a simple shot of two people talking. It’s about the rhythm of the camera, the dolly, the operator — everything working together, like music. On Mickey 17, we designed the shots very methodically.

The storyboard was like a bible, incredibly detailed, and we followed it scrupulously. [See the director's sidebar, "Rhythm and Tempo"] It was almost like sheet music. You had to follow it exactly or you’d lose the rhythm of the film. Bong’s process feels like a mix between composer and mathematician, but in a very poetic way. Every shot is intentional and necessary. Sometimes, as we were shooting, if something wouldn’t work exactly the way he envisioned it, he would change it on the spot, but if you suggested skipping a shot, he’d look at you like you were crazy because each piece was essential to the whole — and it was.

You’ve also described how actors can influence your cinematography — for instance, Brad Pitt always knew where the light was, and Leonardo DiCaprio’s energy shaped your camerawork. What did Pattinson bring to this film?

A very soft and beautiful energy. He’s incredibly professional, very focused, and he listened to Bong intently. He can also be very intuitive. He understood his characters deeply, and it was clear he worked hard to embody them. It was similar to working with Brad Pitt in that Rob was very precise with the light — he knew how to position himself in it — but his energy is entirely his own, and it required a different kind of sensitivity in the way we filmed him. His performance is split between two characters. Mickey 17 is very naïve and pure, almost philosophical, and capturing that energy was like capturing his soul. He has a kind of innocence that reminds me of one of the characters in Voltaire’s Candide.

Mickey 18 is the complete opposite: caustic, dark and dangerous. The story demanded a sensitivity to Rob’s subtle shifts in movement and emotion, especially in the close-ups. It’s an incredible performance; his range is remarkable, moving seamlessly from classical to very modern. This is the second time I’ve worked with him. The first was on The Lost City of Z [AC's coverage] and I couldn’t wait to collaborate with him again.

Did you photograph the two Mickeys differently?

No, we wanted them to feel very much the same visually, and the way they were framed, lit and captured on camera was consistent. Rob’s portrayal of their internal divergence brought everything to life. He played the two characters with subtle physical and emotional differences, much like how twins might appear slightly different. That contrast in character made their dynamic even more compelling. They’re [duplicates], so they had to look nearly identical, but their internal differences created tension.

What made you and Bong choose to shoot with the Arri Rental Alexa 65, and what considerations went into your choice of lenses?

We’d shot Okja on the Alexa 65 and were very happy with the results. We did a lot of lens testing, as I always do. Sometimes I wish I could just pick one or two sets of lenses right away, but I can’t help myself! For this film, we primarily used TLS Vega Prime lenses, which are based on the [Nikon AF-S Nikkor] design, and also Cooke S7/i lenses. Both sets of lenses covered the way we needed, at 95 percent of the sensor. When I shoot with the Alexa 65, it’s not about the sharpness or resolution, it’s about the expansiveness of the frame. I’d love to shoot in VistaVision one day, because I’m drawn to the scale of it. For certain shots, when we needed a smaller, lighter camera, we used the Alexa [Mini] LF.

How did you determine which lenses to use for a given scene?

For scenes that called for a more glamorous, luscious feel — something cleaner on the skin — I used the Cookes. When I wanted a harsher, more contrasty, lived-in look, we used the Vegas, which had a more still-photographic feel. For instance, there’s a battle scene where I used the Vegas because they felt more like photojournalism. But these distinctions are subtle; they exist more in my head. It’s not like comparing Baltar lenses to [Arri/Zeiss] Master Primes, where the gap is huge. The difference was nuanced, but it mattered to me. When I test lenses, sometimes I can tell that no one else really understands where we’re going or what we’ll ultimately choose. It’s often just me making those final decisions. I’ll share my process with my 1st AC, Vincent Scotet, because he sees things the way I do, or with Gabriel Kolodny, my DIT, who has worked on all my films. Our eyes are calibrated together, so they understand me better!

“The world of the film isn’t sleek or futuristic; it’s rough, dirty and lived-in. Part of it feels like an ugly, decaying mall or a massive, grimy garage.”

How did you handle exposure?

My T-stop was fairly open, around 2.8 to 2.8/4. I didn’t shoot fully wide open, though; I don’t like to shoot wide open on large format. The Alexa 65 naturally has a beautiful focus falloff in the background, so I didn’t feel the need to push it further. Our 1.85 aspect ratio already had a slightly more intimate feel, and sometimes I’d have to give it a bit more light to maintain the layers of depth in the frame. We shot everything at 1,280 ISO, which for me is like 640 on film. When I shoot film, I find the stock, which is almost always Kodak [Vision3] 5219 500T, too clean at its base, so I expose it at 640, push it 1 or 1½ stops and work from there. So, shooting at 1,280 feels natural to me. It allows me to light by eye more often. I use it as a baseline, and I create LUTs based on that.

Has your approach to image control changed as cameras have become more sensitive and tools for image manipulation more sophisticated?

Honestly, I haven’t changed much over the years. I’ve never been a fan of having everything overly controlled. That’s what I loved about film: There was always an element of magic, a lack of control, that made things exciting. With digital, I’ve seen the progress and improvements, and while it’s great, I’m cautious about adopting new tools or techniques.

For instance, I’m very particular about color; I don’t like excessive or artificial- looking colors. On this film, there’s a scene where the red in a costume just wouldn’t register properly — it looked too digital, too artificial. Gabriel and I drove ourselves crazy trying to fix it. No matter how we adjusted the camera settings or LUTs, the red didn’t look organic like it would on film, or even to the naked eye. The problem was partly the costume and partly the daylight, which was mixed with HMIs coming in from outside; we were in a gigantic hall designed by a renowned English architect. We brought in other cameras from Arri and tested different sensors. Eventually, we went back to the LUT and toned down the red during the shoot.

A lot of people don’t see color well — they miss the nuances — and sometimes, I feel like a freak with how much I notice color! Recently, I was at the Louvre with my wife, looking at a pre-Renaissance painting, Cimabue’s Maestà. There was this veil under the Madonna and child, and I noticed it had a very faint pink tone. My wife insisted it was gray, but I was certain it was mauve to pink. It’s like a delirium about color! Gabriel has the same obsessive sensitivity to color, which is invaluable when we’re working together. It’s almost like the opposite of colorblind: hyperawareness.

You’ve spoken about the importance of entering a director’s head and heart when you collaborate with them. Were there differences in that process with Bong during your second collaboration?

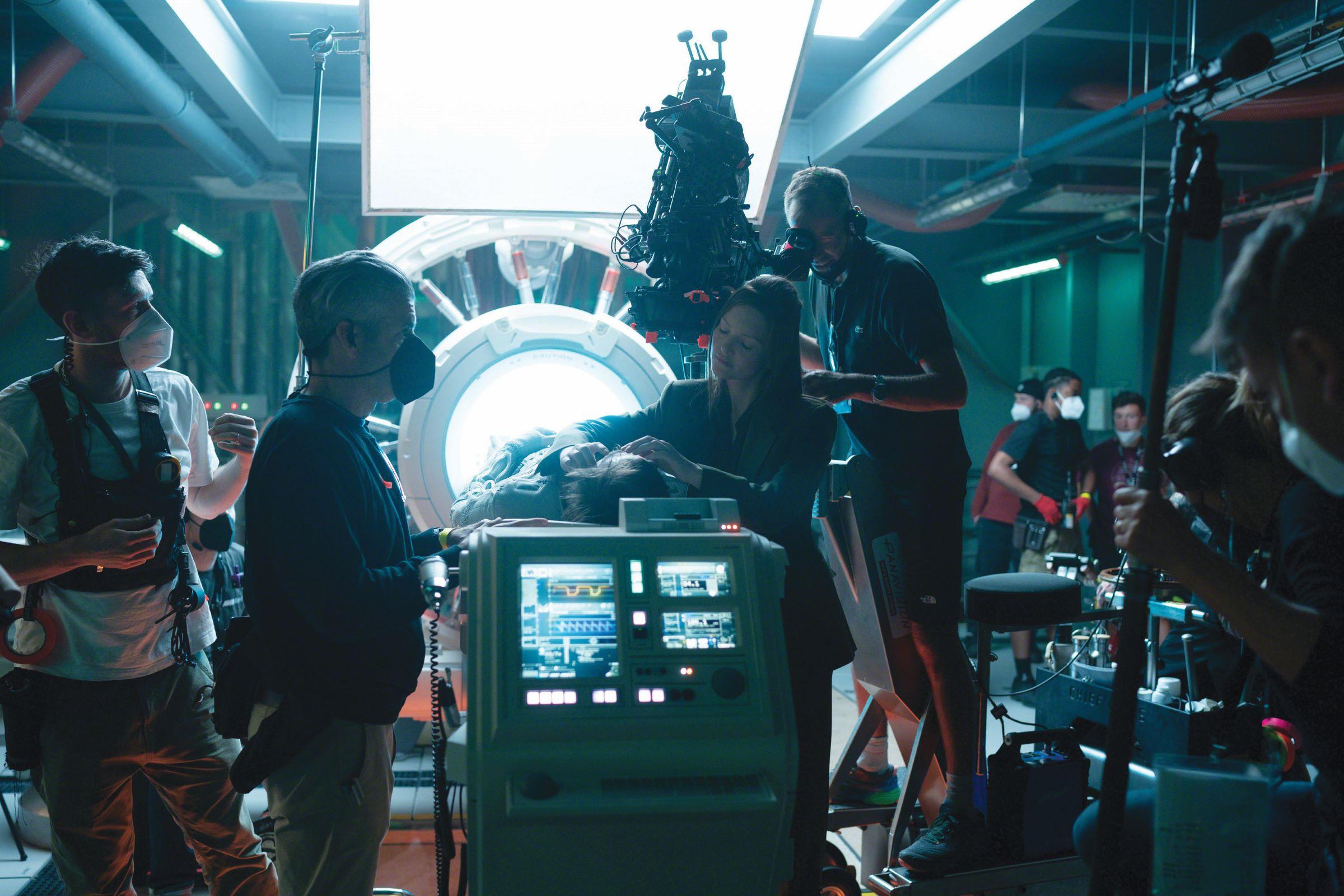

Some directors often see things in ways they can’t always articulate, so you have to develop a feel for what they want. Every collaboration is unique, but with Bong, the most important thing is to get into his head. You have to open yourself up to his vision; otherwise, you risk getting stuck in your own technical objectives. It always comes back to the characters and the emotional essence of the scene. For Mickey 17, the process was incredibly precise. It was like playing an orchestral symphony, with Bong as the composer and conductor. This level of planning made it a challenging shoot, especially on a large stage [at Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden] with so many moving parts, schedules, producers and logistics. It was a huge machine, and you had to keep up with its momentum.

At the center of it, though, was Bong, one of the most creative artists in modern cinema. My gaffer, John “Biggles” Higgins, is a good planner, which was crucial. We had some large sets that could intimidate anyone, but Biggles handled it with ease. My key grip was John Flemming, another legendary figure in England. My camera operator was Chris Bain, who is also English and incredibly talented. The only people I brought with me were Vincent, from Paris, and Gabriel, from New York.

"The story demanded a sensitivity to Rob’s subtle shifts in movement and emotion, especially in the close-ups.”

How would you describe the looks you sought for the environments in the film?

The world of the film isn’t sleek or futuristic; it’s rough, dirty and lived-in. Part of it feels like an ugly, decaying mall or a massive, grimy garage. At the same time, there’s this vast, sprawling city in motion filled with people heading toward a distant planet. Each part of the film has its own distinct color palette. It’s all about finding the balance between the rawness and the beauty. On Earth, at the beginning of the film, it feels almost like a Renoir painting, with a more classical and vibrant palette.

We designed the spaceship with distinct visual identities for different sections; [production designer] Fiona Crombie and I worked to give each part of the ship its own feel through color and lighting. I used a lot of soft toplighting, and there was a fair amount of color, especially in the scenes with Toni Collette and Mark Ruffalo. Mark plays the head of the mission to the planet, and his costumes and environment have a flamboyant, Baroque quality; I wanted Mark’s scenes with Toni to feel hyper-realistic, almost as if they were stepping out of the screen. Meanwhile, with Robert Pattinson and Naomi Ackie, the approach was softer. Their scenes have a more pastel, slightly flashed look. The scenes on the planet are almost monochromatic with a hint of green, [echoing] the military tones in the characters’ outfits. It’s a bit grungy and rough, not soft or clean. I used the Vega lenses to enhance this texture.

How much of the color and contrast do you build into the lighting on set?

We like to create as much as possible on set. It reassures me to see the look during filming. The notes for the dailies are usually, “Don’t change anything. Just transfer it exactly as it is.” Damien Vandercruyssen from Harbor [Picture Co.], who is very good, was our dailies colorist and our final colorist. I was on site at Harbor’s new London facility for the main grading, and we finalized the grade with Bong in New York for a couple of days.

With Mickey 17, as well as The City of Lost Children and Alien: Resurrection [AC's coverage], it’s clear science fiction interests you. Why?

I’ve always been fascinated by science fiction. I’ve wanted to work on a true sci-fi film for a long time, though I haven’t quite achieved that yet. Treasure of the Bitch Islands [1990] is perhaps the most science-fiction project I’ve done. But the science-fiction films I’ve worked on have all been very different from traditional sci-fi. The directors I’ve collaborated with aren’t primarily driven by the sci-fi elements, which is actually a good thing [because] it brings depth to the projects. Still, if I’m being honest, I haven’t yet worked on the kind of pure science-fiction film I dream of making.

What’s an example of that?

Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin [AC May ’14]. To me, that’s one of the greatest science-fiction films. Of course, there’s 2001: A Space Odyssey [AC's coverage], which is iconic, and I also love Dune — both David Lynch’s version [AC Dec. ’84] and Denis Villeneuve’s [AC's coverage here and here] are wonderful. I’d love to make a film about the void, about emptiness and how terrifying it is. I’ve always been fascinated by scary films, and science fiction has the potential to be deeply unsettling. But the line between science fiction and reality is so blurred now. Things that once felt impossible are happening all the time.

TECHNICAL SPECS

1.85:1

Cameras | Arri Rental Alexa 65, Arri Alexa Mini LF

Lenses | TLS Vega Prime, Cooke S7/i