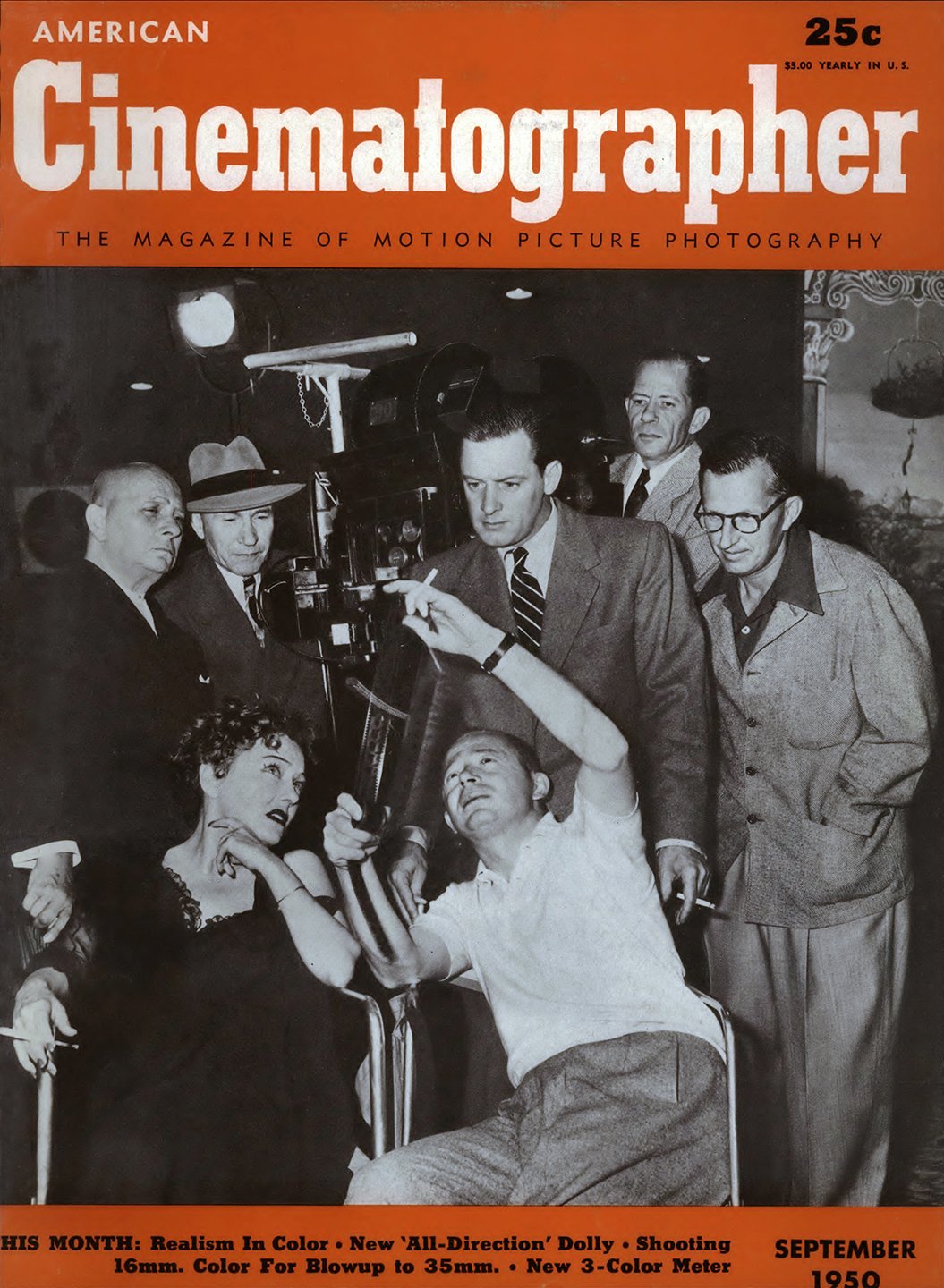

An Old Master Shows Some New Tricks on Sunset Boulevard

“I believe that a motion picture should be alive and not dead — spontaneous instead of calculated,” says director of photography John F. Seitz, ASC.

In the make-believe world of sunshine and celluloid called Hollywood, the terms “stupendous” and “colossal” have been over-used to the point of becoming synonymous with “fair” and “mediocre.” This being the case, when a really great motion picture does appear, it is difficult to find fresh superlatives with which to adequately describe it. If such words could be found, however, they would most certainly apply to Paramount’s masterful production of Sunset Boulevard. The picture tells the story of a woman, an aging former star of the silent screen, who refuses to accept the fact that the parade of life has passed her by. But more than that, it is the story of one sharp facet of a fabulous industry — a faithful (if somewhat special) slice of life out of a glamorous pattern of heartbreak well known to those who work in the world of the motion picture.

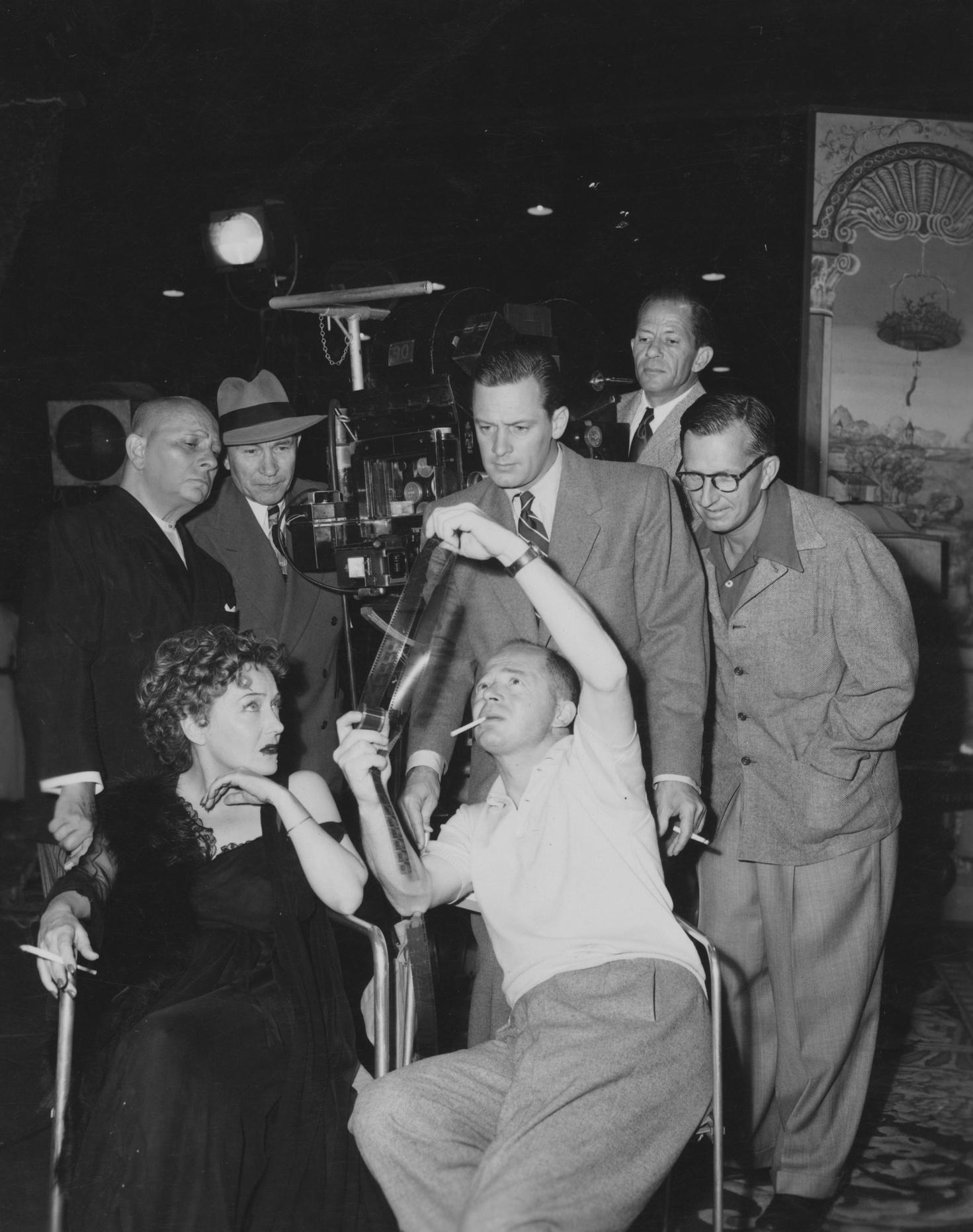

To capture the subtleties of this story and to recreate in a modern context the ghostly glories of a gilded era now past, Paramount assembled a rare assortment of craftsmen. The writing-producing, directing team of Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder chalks Sunset Boulevard up as one more triumph in a long series of artistic and box-office successes. Gloria Swanson emerges from semi-retirement to score in a performance of magnificent stature — one that will undoubtedly add a gold “Oscar” to her mantlepiece. But credit for this outstanding film belongs equally to the men behind the scenes — to Hans Dreier and John Meehan for their inspired art direction, to Franz Waxman for his provocative musical score, and especially to John F. Seitz, ASC, for his brilliant job of photography.

It is fitting that the camera should play an important role in the telling of the Sunset Boulevard story — for here is a plot conceived expressly for the screen — not adapted from the latest best-seller or Broadway stage hit. It is a purely cinematic vehicle — and as such, it depends strongly upon the subjective eye of the camera to tell its intense story.

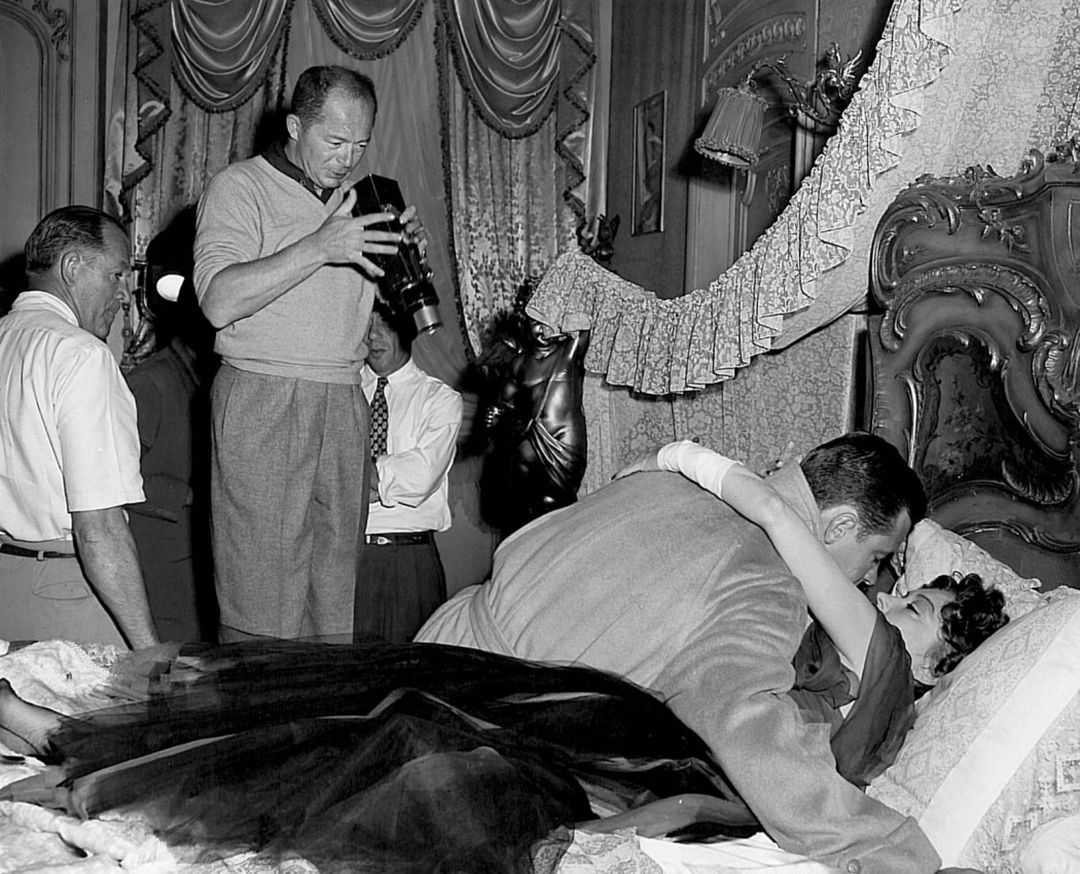

The photography in this film is honestly realistic, yet suffused with an aura of other-worldliness that perfectly complements the mood of the story. It does full justice to the lavish, decadent elegance of the ghostly mansion in which lives the idol of another age. It strikes precisely the right note in portraying the heroine — unmistakably middle-aged but a commanding figure, and still, in her own way, a beautiful woman. There is no varnishing of the truth for manufactured glamour, no mushy diffusion in an attempt to transform a 50-year-old woman into an illusion of 18-year-old prettiness. Had this latter point been less honestly handled, the entire film would have lacked credibility.

Sunset Boulevard depends upon photographic mood for much of its dramatic effect. Thus, the more intense sequences are played in a low-key faithfully motivated by the time of day as well as locale. The restrained lighting in these sequences leads the audience to focus its attention sharply upon the action and dialogue of the players in such a way that the performances could also be kept effectively restrained.

Wide-angle shots involving extreme depth-of-field are used most forcefully in this film. In one scene, the bandaged wrists of the actress (the result of a suicide attempt) dominate the foreground of the frame, while her young lover moves freely about in the background. Both planes are held in sharp focus. In another scene, the white-gloved hands of the butler are seen playing the organ in the foreground, while background action takes place in a widely separated plane.

To achieve this extreme depth-of-field it was necessary to use a greatly intensified light level and to lantensify the film stock in order to stop down the lens aperture sufficiently. The lantensification process added about two stops to the speed of the film — allowing a scene lighted for f3.5 to be shot at f7. This method was used in shooting about 15% of the total footage in the picture.

[Editor's note: The “lantensification” process would intensify the sensitivity of the film stock through a chemical treatment or its exposure to low levels of light — similar to “flashing” the film. This was done prior to shooting and we do not know exactly which process Seitz employed here.]

In one scene, the key-light illuminating the players actually came from a practical lamp appearing in the composition — a minimum of fill light being used to soften the shadows. This might be described as source lighting carried to the ultimate degree. Intensification also made possible the filming of realistic night exteriors and street scenes actually shot at night instead of in daylight with the use of filters.

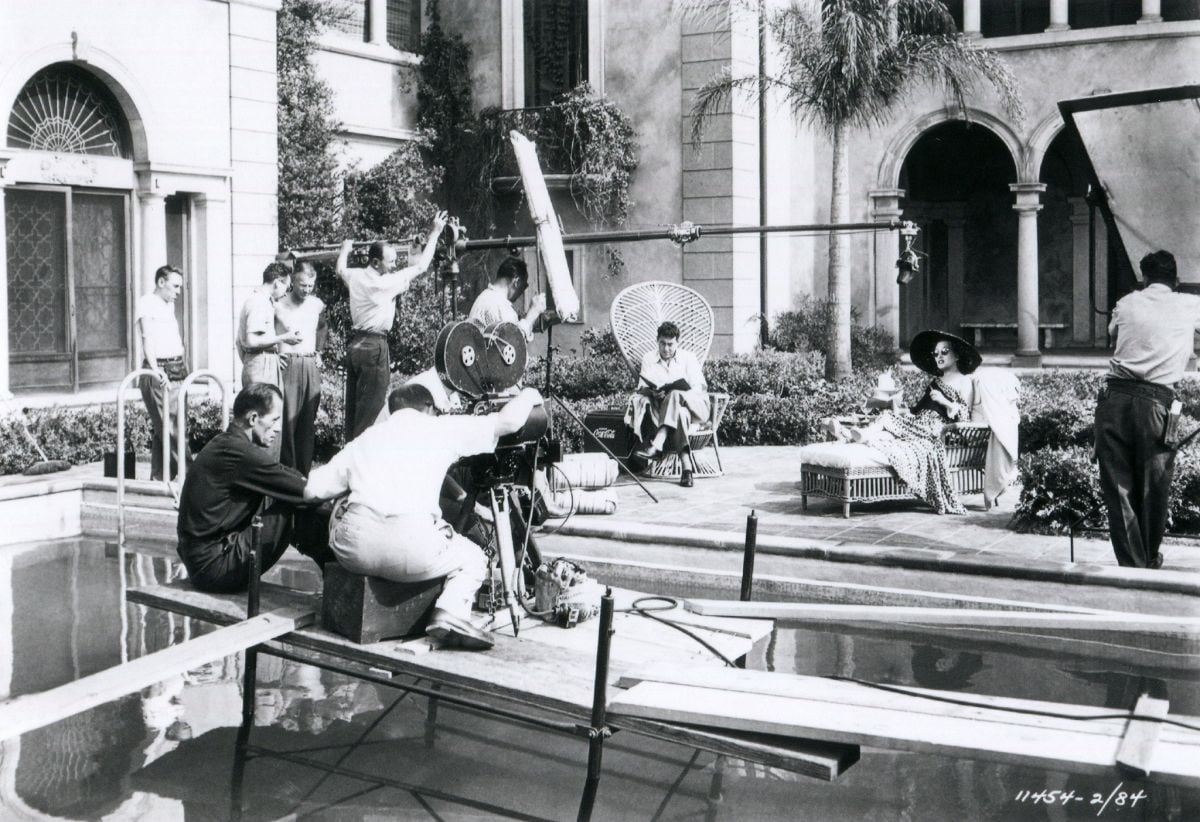

The quest for realism led to the filming of many sequences in actual locales, including the Paramount Studio itself, filmed at night for the first time; a section of the Bel-Air golf course; exteriors of Schwab’s drugstore, famed Hollywood hangout; and several apartment buildings and stores. A deserted 25-room mansion, built about World War I, served as an ideal exterior set for Miss Swanson’s presumed home. The only thing that it lacked to fit the description in the script was a swimming pool. So one was built — and then filled in again after completion of shooting, to conform to the wishes of the owner.

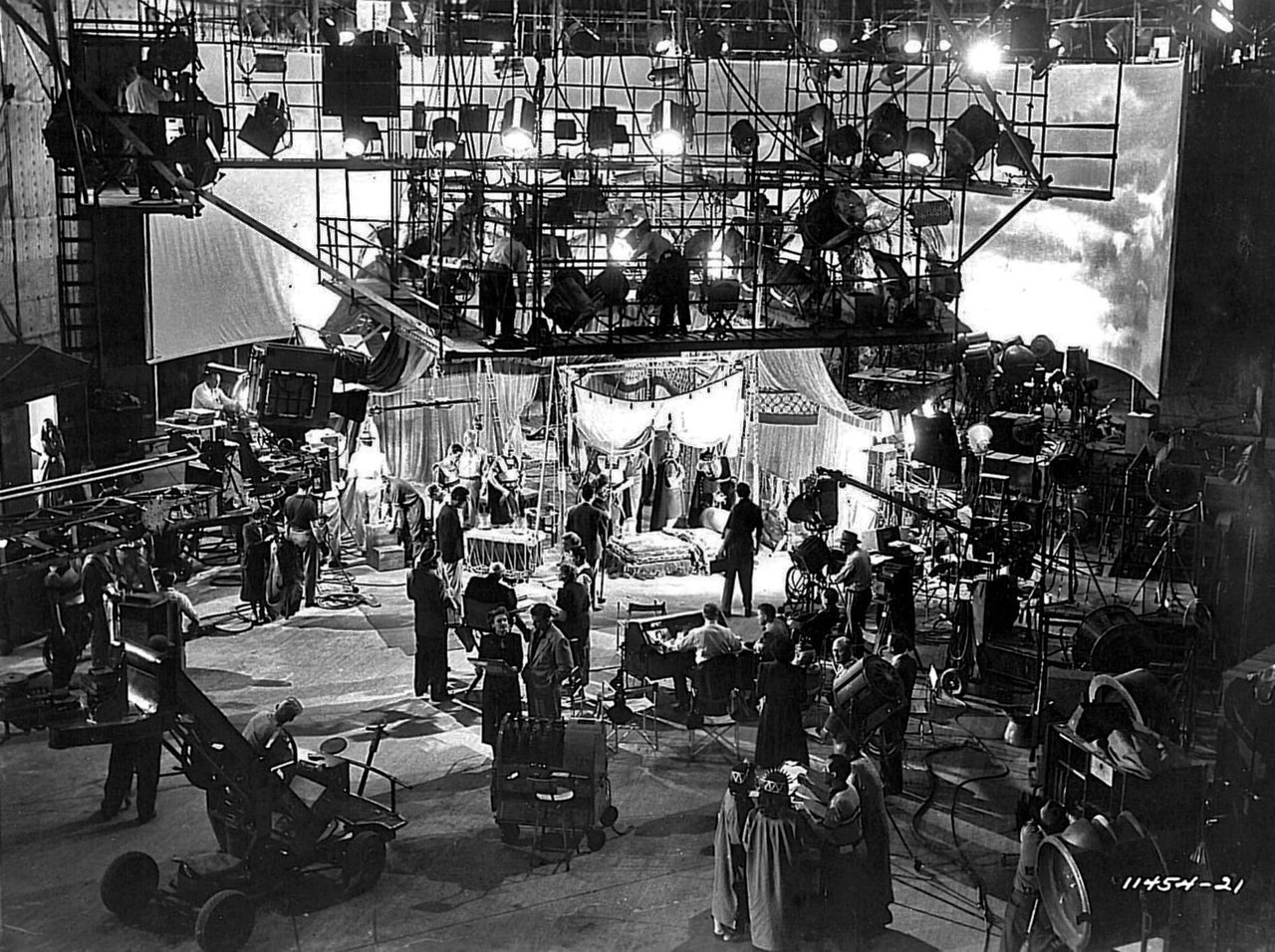

The interior of the house, built on the set at Paramount, was cluttered with ornate furniture, a gold-plated piano, a pipe organ, a motion-picture screen on the wall with a projection room opposite, heavy carved tables and chairs, a huge fireplace, ship models, a Turkish waterpipe; and a lavish bed shaped like a gondola with a curved prow, golden cherubs, and a silken canopy.

The interior of Schwab’s drug store was duplicated down to the last toothbrush. Actual merchandise was brought in to fill the counters and shelves. The soda fountain was a practical one, dispensing real ice cream, sandwiches, etc. Even the licenses were borrowed from the drug store and hung in their proper places.

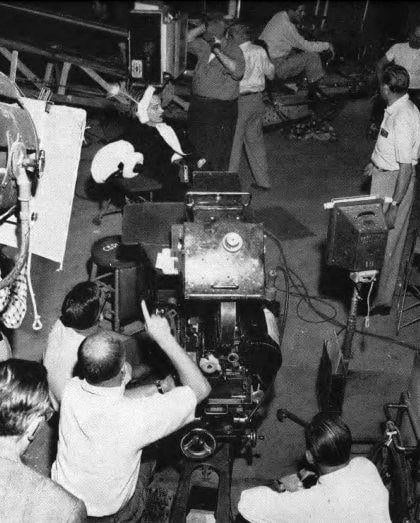

An extraordinary scene is included in the sequence which shows the young writer’s body discovered floating face downward in the swimming pool. The effect is that of looking up through the water from the bottom of the pool to see the victim’s face and the police photographers standing on the pool-edge and shooting photographs in the background. Placing the camera underwater would not have given the desired effect, since the water’s surface acts as a mirror and would have prevented anything outside of the pool from being seen. Instead, a giant mirror was placed under the water. The camera was set-up alongside the pool and the reflection in the mirror was photographed. The effect is striking, to say the least.

A compressed-air gun activated by an electric solenoid valve was used where Miss Swanson presumably fires a revolver at her lover, missing his head by inches and breaking a heavy plate-glass door. This gadget, accurate to the fraction of an inch when set up properly, resembled a surveyor’s instrument. The “bullet” was a half-inch steel ball bearing. The “gun” had a striking force of 180 pounds of pressure per square inch. Far less than an actual firearm bullet. As planned, it shattered the glass at the right spot each time fired, missing the actor.

To film a sequence where Miss Swanson and her boyfriend do the tango, director of photography Seitz used a dance dolly — a small platform on wheels — placed immediately in front of and attached to the camera which, in turn, was also mounted on a moveable platform. Men behind the camera moved both the camera platform and the dolly, thus permitting a shot of the dancers making a complete 360 degree turn around the room. The basic idea is far from new; Seitz first introduced it when he filmed Rudolph Valentino and Alice Terry dancing the tango in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse back in 1921.

Seitz approaches a film with the idea of letting the photography tell the story in the most interesting and dramatic manner possible. With this in mind, he pays a great deal of attention to the presentation of sets as well as proper photography of the players.

“I always try to dramatize the locale of a story photographically,” he explains “because in most cases the setting has a great deal to do with the drama of the situation. This was true of Double Indemnity, Five Graves to Cairo, and The Lost Weekend. It was especially true of Sunset Boulevard, because in that film the decor and mood of the principal setting was an unmistakable clue to the personality of the main character.”

As a cinematographer, Seitz is a craftsman of great professional integrity and he proves this in his working approach to a film. Where another cameraman might be inclined to play it safe (especially in this day of restrained budgets) by using tried and true formula techniques, Seitz doesn’t hesitate to “stick his neck out” to try for the unusual and original effect — and he invariably comes up with an exciting result.

“It is possible to make a motion picture too polished, too glossy, and too perfect in every detail,” he points out. “The result is a dull and lifeless film. I believe that a motion picture should be alive and not dead — spontaneous instead of calculated. I have no preferences as far as subject matter of assignments is concerned — as long as I am given scripts that can be made to ‘come alive’ through a well-coordinated combination of acting, direction, and cinematography.”

Far from being a trickster out to create an effect for its own sake, John F. Seitz, ASC remains, after more than 30 years in the industry, an alert experimentalist, constantly searching for new approaches and original camera techniques to make the motion picture a more live dramatic medium.

He has been at the top of his profession since the days of Valentino; yet there are no cliches in his style — as modern as tomorrow, rugged, forceful, and (above all) alive. Pictures like The Lost Weekend, Double Indemnity and The Big Clock prove the force of his photography as a story-telling instrument — and he insists that cinematography must exist to tell the screen story, rather than to stand out as a separate artistic entity. Sunset Boulevard more than proves his point.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.