Bill Butler, ASC on His Transition From Tape to Film to Jaws

At a time when some shooting on film were pondering a switch to video tape, Butler did just the opposite — and went on to become one of America’s top cinematographers.

This piece first appeared in American Cinematographer's February 1977 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

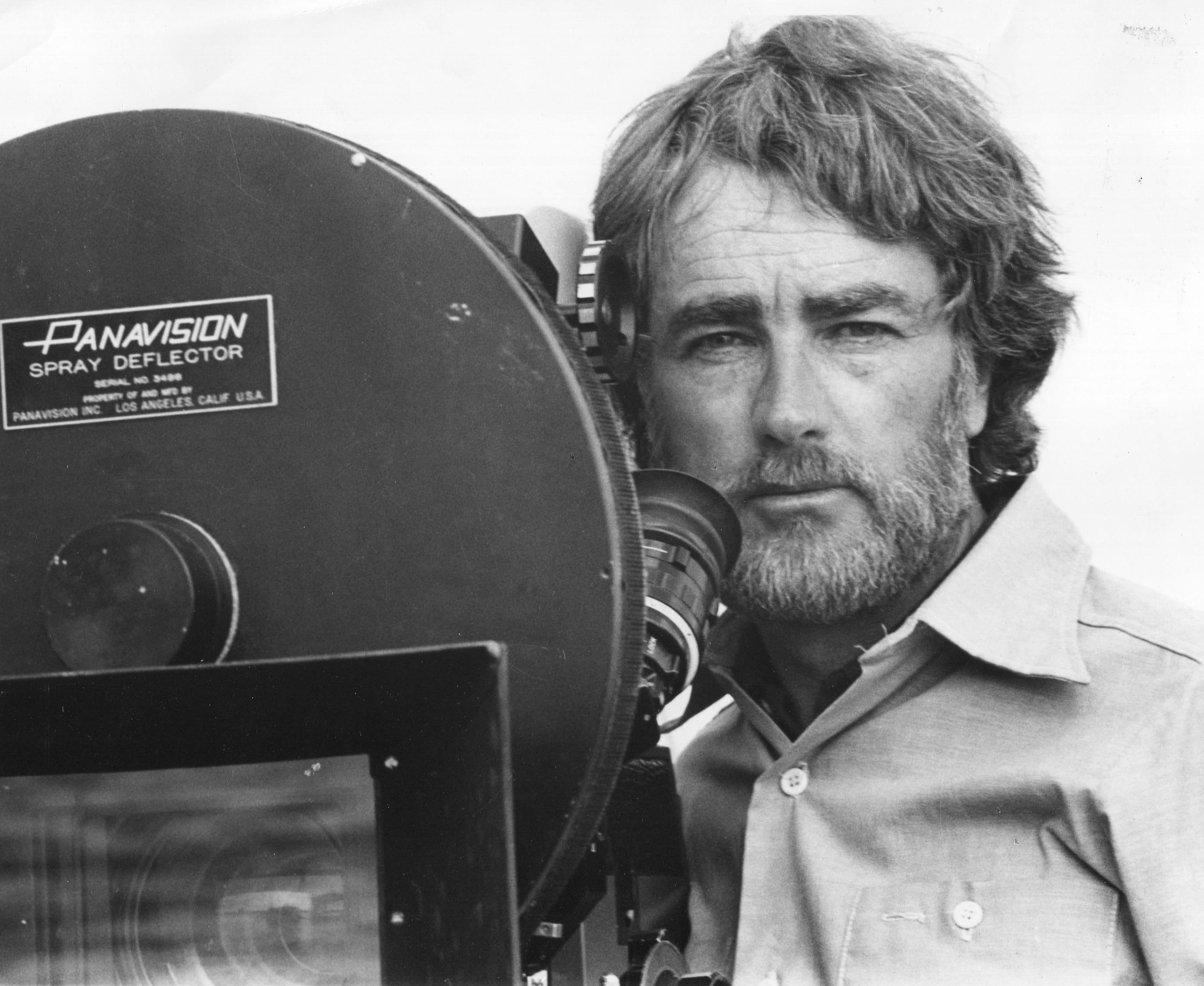

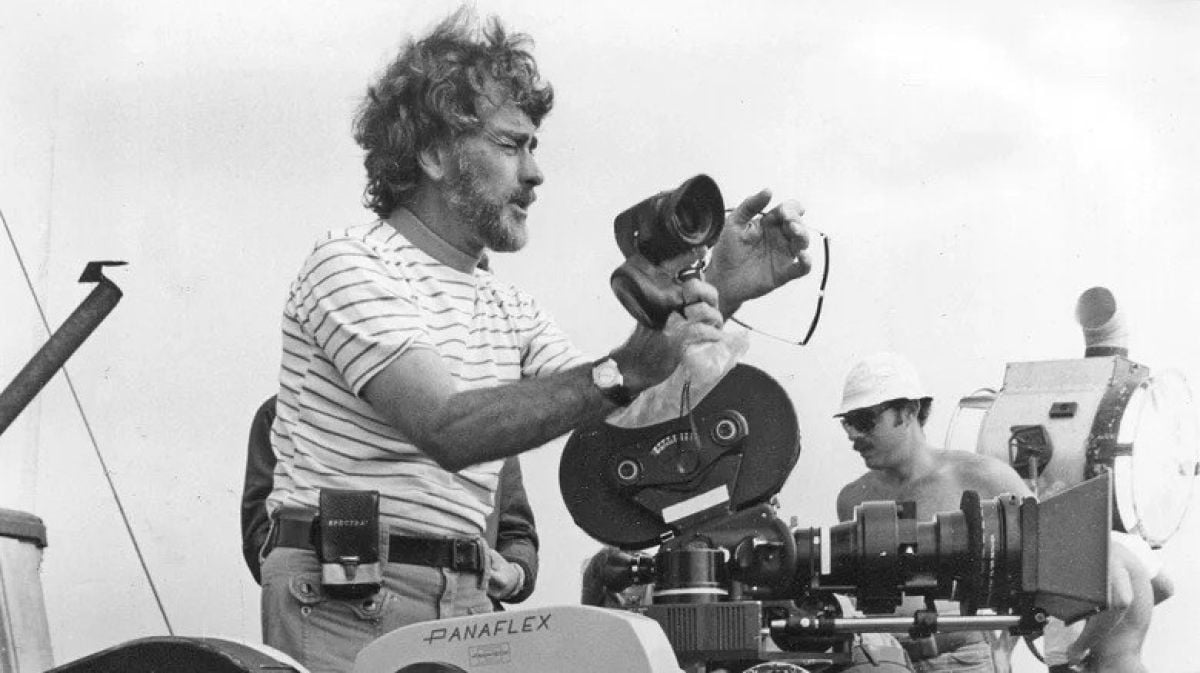

For Bill Butler, ASC, life truly began at 40, when he made the transition from tape engineer in a Chicago television station to become one of the top-ranking cinematographers in America today.

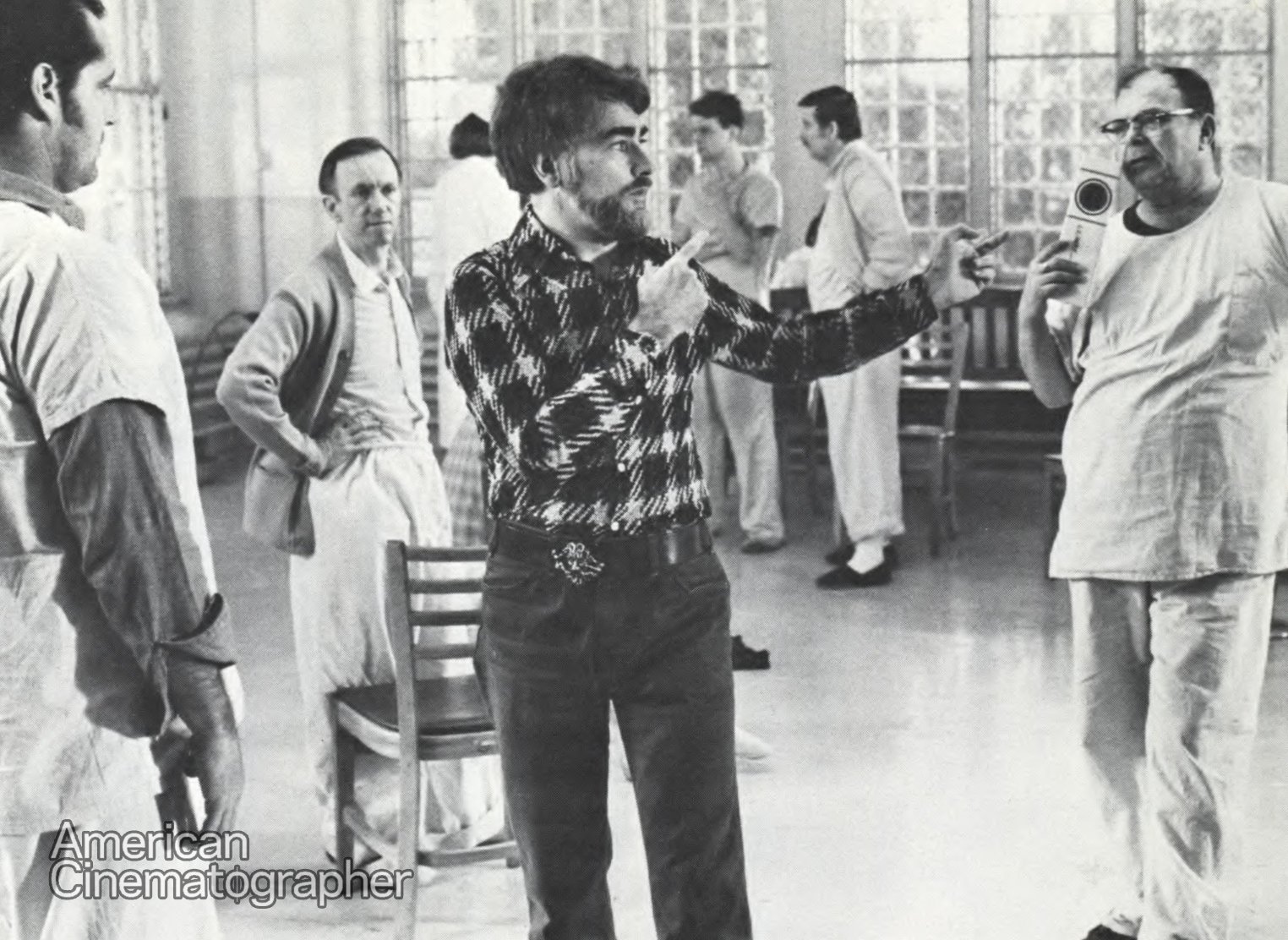

In the few short years since his arrival on the west coast, Butler has worked with such eminent directors as William Friedkin, Francis Ford Coppola, John Boorman, Jack Nicholson, Bill Sargent, Lament Johnson, Steven Spielberg and Milos Forman, to name a few. The outcome of these associations has been a roster of feature films which includes The Rain People, The Conversation, Drive He Said, The Execution of Private Slovik, Hustling, Fear on Trial, Lipstick, NBC's three-hour Raid on Entebbe and Demon Seed.

Two films photographed by Butler, Jaws and (with Haskell Wexler, ASC) One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, have between them grossed over one-quarter-of-a billion dollars.

Bill Butler certainly has come a long way from those early days in video tape, and I was determined to find out what kind of person he is, what his filming philosophies are and what effect his success has had on him and his career.

I finally caught up with the soft-spoken Butler at MGM on the set of Demon Seed. He asked me to screen his most recently completed film, The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings, about which he was very excited. We set up a time to talk, and the following is our conversation:

You started out as an electronics engineer at Station WGN in Chicago. You had been highly trained in that field and, for over 20 years, had made it your career. What caused you to change careers in mid-life … to leave a successful career in tape for an uncertain future in film?

It all started with this kid in the mailroom at WGN; he was just a high school kid then and, at first, I mostly just hollered at him. One day the station needed a floor manager, so we took this kid, put earphones on him and told him where to point. The next thing I knew he got a show to direct. The kid’s name … Billy Friedkin. Well, Billy and I became friends and we started doing experimental tape shows for the Television Academy. We would go out to the educational television station and use their equipment, which they were inclined to let us use for free. We would get someone to compose the music for it, solicit any singer who was in town at the time to appear in it, put together a group of musicians to play for it, and we would have our big extravaganza — all at no cost. Billy was great at doing this. It wouldn’t cost anybody anything and, best of all, it would come out looking great. We would conjure up these ideas and do them just for the fun of doing a production. Pretty soon we ran out of adventure like that, so one day Billy said, ‘‘Let’s shoot some film.” Now, I had never shot film in my life, but Billy had this idea about some ballet dancers dancing up and down the streets and fire escapes of downtown Chicago. I told him to get me a camera and we’d do it. God knows what the exact idea was, because Billy never did anything about it, but he did succeed in exciting me about the possibility of working in film.

The seed was planted, obviously, but how did you get a chance to cultivate it?

As a public service the station would tape a different religious service each Sunday. While working on these tapings, I got to know some of the people from the Church Federation, an organization responsible for all the publicity and advertising of the various religious groups in the Chicago area. They called me up one day and asked if I would shoot a film for them for free. They said they had only $500 with which to make the film, and could it be done for that? Billy and I talked it over. Well, $500 was more money than either of us had seen in a long time and, as neither of us had ever shot an inch of film, we figured it had to be enough. So we started shooting our first film. We took the $500 and bought film stock and talked a good editor into cutting it. All quite logical, but now the money is all gone and we don’t even have a camera. So we go out, rent a camera and charge it off to this religious outfit. The same with the lab — we charge it all off. We just about have our final cut and the roof falls in. The bills have finally reached the group that hired us and, instead of $500, we are up to $2,000. Well, they are screaming at us and all we can say is: ‘‘Look at the film. Look at the film.” They do — and love it. Never the less, they still can’t believe what we’ve done. I’m scared to death. I’m going to jail... I just know I’m going to jail. But there sits Billy, not quite sure what he is going to say to them, but knowing he is going to handle it. ‘‘Well,” he says, ‘‘why don’t you fellows take this film to WGN and get them to pay for it?” So they do — WGN is only too glad to pop for it — and we win an award at the San Francisco Film Festival. It’s a good dramatic film and, you know, more people have probably seen that film than any film I’ve ever made — outside of Jaws, of course. Every television station in the United States has, I think, played it at one time or another.

What next? That one taste of film couldn’t have made the transition from tape to film for you, could it?

No. You would have thought the television station would say: ‘‘Okay, Butler, you’ve done enough tape. Go make films.” They loved the film but made no plans for my future in film. By now I had film fever, but knew I wasn’t going anywhere there. The wall showed up. I’d been against it for some time, but was just now beginning to see it. I wasn’t going anywhere and my salary wasn’t going anywhere. On top of that, I was bored with doing the same thing every day. I got to thinking that, for the sake of my own head, I ought to do something about it. At which point Billy said: ‘‘Let’s go make documentaries.” I said: ‘‘Sure, that’s okay for you, but I’ve got a family and I'm 40 years old. No way!” But Billy, with his need for a cameraman and his ability to get inside your head and inspire you to greater things, induced me to shoot a documentary, but not leave my job yet. So we shot nights and weekends on The People vs. Paul Crump, knowing full well that when the station found out we would be fired, for it was prohibited to shoot film while working live television. Anyway, we took Paul Crump to the San Francisco Film Festival! We got a huge award, which was very flattering. In the meantime, bills were piling up and it became necessary to find a sponsor. We found one at ABC Television — a man named Red Ouinlan. He paid the bills and we kept working. During this time we made a number of documentaries and one of them, A Tale of Two Cities, is in the Library of Congress as part of its permanent record. About this time, I was beginning to realize the undeniable power of film. Meanwhile, Billy got an agent, moved to the west coast and went to work for Wolper. I stayed on in Chicago shooting documentaries and eventually went to work for Wilding Films.

You continued to work, doing such things as the titles and outdoor footage for The Fox, a feature in Australia, and then your first really big break: a low-budget feature entitled The Rain People with a young director named Francis Ford Coppola. How did you get that job?

Basically, the thing that got me the job was Friedkin’s recommendation to Coppola that he hire me. Billy had met up with Coppola and they had become good friends. Coppola was having some difficulty in getting The Rain People started, inasmuch as it was his first feature after having done a big studio musical and this was a very personal film of his which he wanted to do with a small crew in a small way. Billy knew I could pull that off. He had worked with me and knew that I could work very light-weight, with very little equipment. So, with just a few quartz lights, two cameras and one little van carrying all of the electrical and grip equipment, we roamed across the country shooting this feature, which turned out to be a rather good-looking film. I mean, lightingwise you would not realize it was lit only with open-faced quartz lights. There wasn’t a light used on the production that had a lens in it, except for a couple of little inky-dinks (maybe four). The rest were quartz lights — harsh, cold, unattractive — and to learn how to use them gently was the trick.

You continued to do feature work in the midwest, eventually working your way to the west coast, where you did several movies for television and then the critically acclaimed The Conversation.

Not exactly. Prior to The Conversation I did some shooting on The Godfather — the first one — for Coppola. Gordon Willis and I were friends and, as he had gone on to another picture, he thought I would be a good choice to do the west coast shooting on the project. So I ended up finishing The Godfather for Coppola, and then went on to do The Conversation.

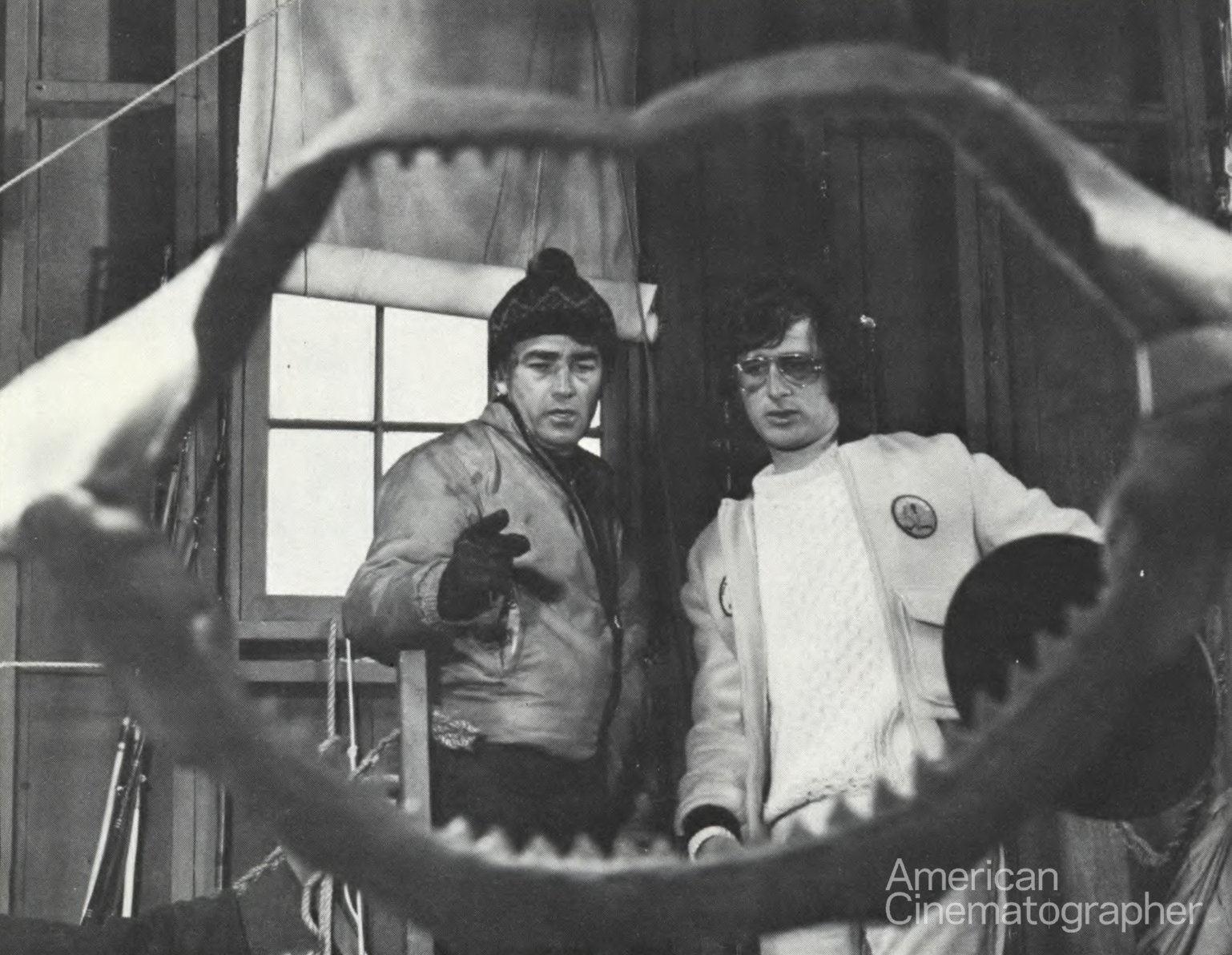

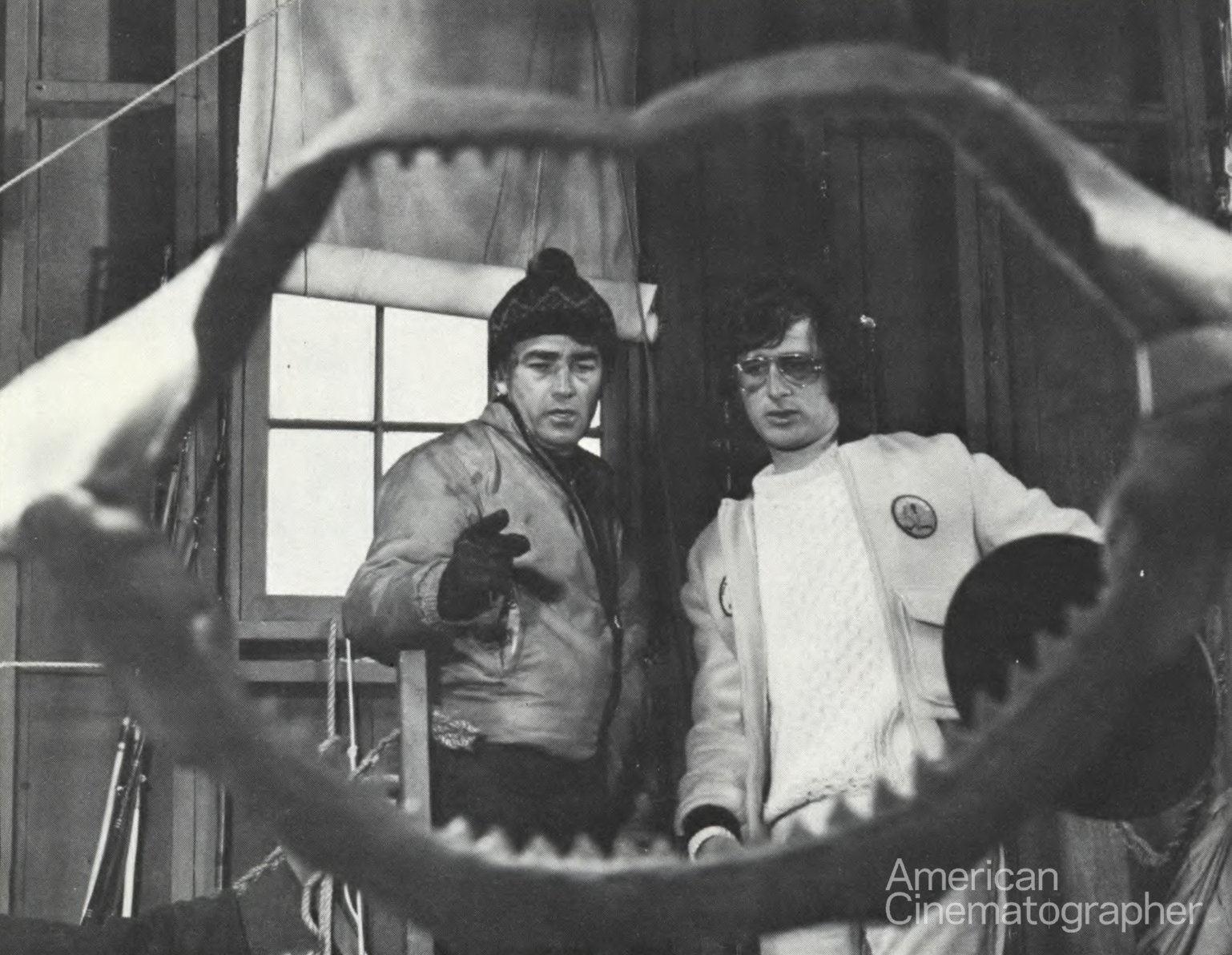

From there you went on to work with yet another young director, Steven Spielberg. How did you happen to get involved in shooting Jaws?

I had worked with Spielberg before on a television show. I heard he was going to do Jaws and it sounded like an exciting project, an original idea, so I went after it. Oftentimes you don’t know beforehand how good a script is or how well anyone is going to do it, but if you’ve worked with an exciting director that you feel is talented, and I certainly felt that way about Spielberg (one look at Duel and you know you’ve got a genius working behind the scenes), then you want to work with that kind of people again. They are young and full of ideas. They tend to create out of the moment, and I still have a love for those early days of documentary work when you had to do just that — create out of the moment.

Explore More on the Making of Jaws, Shot By Bill, Butler, ASC:

AC Behind-the-Scenes Gallery: Jaws

But as a cameraman, doesn’t this spur-of-the-moment creativity sometimes create problems for you?

Not really. One of my plus qualities, I feel, is my ability to invent on the spur of the moment, and I like to exercise that ability. It is exciting for me to use my mind that way. Young directors challenge that ability in me. This kind of creativity does not cause pressures for me — I enjoy it. I enjoy meeting an impossible challenge and, by being creative and inventive, getting around what to some people would be stumbling blocks or impossibilities.

Can you give me an example of what you’re talking about?

On Jaws we had it every single day. We literally had a constant challenge — the weather, the physical impossibility of holding boats still, plus the desire not to shoot this picture from a normal point of view. At the same time, we did not want to do sensational things with the camera, but rather find a point of view that would make the film successful. We met that challenge and, judging by the grosses, quite successfully. As for the point of view — we shot most of the picture at water level, even though people are not aware that we are that close to the water. We put the camera in a water-box (a piece of equipment originally designed by Panavision for use on Deliverance) that could be submerged to a point where the lens itself would barely be above water, but if a wave came along it wouldn’t cover the camera; it would cover only the lens, which was protected by a piece of glass. Thus, the whole point of view of the film keeps you so close to the water that, after you watch the film for a while, you begin to get the feeling that there’s something out there in the water and, in the ocean, that could only be menacing.

Your photography does not seem to have a specific look, but rather you would appear to have the ability to create visually in a variety of styles. Can you explain this?

Well, I change the look on each picture I do quite a bit in terms of lighting style because I love lighting. I love to create different moods with lighting — to take off in different directions. Before you can do what you want artistically, you must be in full control of your tools and understand them technically. I am strong on composition. My pictures must be beautiful for me, even if the subject is a little revolting. It may be corny to say that you really have to see through the eyes of a child, but there is a kind of beauty to be seen in everything, if you have an eye for it. I try to understand what each director wants and put it on film in a way that is faithful to his inspiration, yet add to it my own ability.

Earlier on you said you liked the challenge of working with young directors because of their creativity … their fresh approach to film-making. Did this philosophy prove valid on Bingo Long when you found yourself working with yet another young director, John Badham?

Yes, John certainly was very creative and daring, which is heartening to see in someone who is directing his first feature picture. He has the gambling spirit and the confidence to try his own ideas, and that is important. In this instance, his ideas ran along the vein of reviving the old techniques used in the pictures of the Thirties, Forties and Fifties — dissolves, wipes, headlines spinning on the screen — old techniques that we have almost forgotten. In those days, during the period of transition from silent to sound, they had just discovered the optical printer I think, because they used all the optical devices they could think of. Today they are considered so corny that we never think to try them. John used them all, and very successfully.

Besides the optical effects, did you use any other devices to reinforce this period feeling?

Yes, I suggested to John that, in order to set the period, he might use an old newsreel at the beginning of the picture. He bought that, and so the picture actually starts off with a newsreel. Also, in order to continually reaffirm that period feeling, we faded the color and warmed it, not exactly to a sepia tone, but to a sort of golden look, which gave you the feeling of age.

Was this alteration of the color quality accomplished in the lab or did you do it in the camera?

We hear a lot of talk today about special color filters used on the camera, especially salmon (or coral) filters, but I find it totally unnecessary to do that when the lab has the ability to do it all. You can change the color in the lab in just about any way that’s within the range of the color balance of the film. The lab should be able to do as much for the color of the film when it gets there as you do for it when you photograph it. And if you photograph it knowing ahead of time what you are going to do with it, you will set your exposures accordingly and you can help the effect. In this case, by giving the lab proper detail in the shadow areas, it was possible for them to color tone it so that those shadow areas would be as right and golden as we wanted them to be. I try to have a dialogue with the lab so that they understand what it is I want. I pick my lab, to a great extent, according to their ability to understand what I am trying to get out of their capabilities. When you are trying to make a feature film, you don’t want something that is just turned out; you want something that has an artistic touch put to it. And now you are talking about a talented timer like Bob Van Andie, who has the eye and the ability to get the colors that you want onto the print. It is possible to have an excellent negative and get a very poor print — and it is also possible to have a very poor negative and, with the help of a skilled timer, pull a good print. There is so much a good lab can do and, believe me, their "artwork” on a film should be as great as the work the cinematographer puts into making the film. On Bingo Long I dealt with Technicolor and Skip Nicholson. Skip is especially helpful and has the ability to understand what you are trying to do with a film, even if it is out of the ordinary.

Your lighting on Bingo Long, which has an all-black cast, is particularly effective. Do you have a special technique you use when lighting blacks?

My philosophy in lighting blacks is that they should look as natural as possible. In the past, cameramen have found that if they get into a tough spot lighting a scene that involves both light-skinned and black-skinned people, the approach is to backlight them and glance light off their faces. I don’t think that technique creates a very pleasant look, because the light bouncing off the face comes back to you as almost pure light. It doesn’t bring back with it any of the look of the person, any of the detail of the face, any of the color of the skin. So I approach it in an entirely different way. I like to use direct soft light — which is the very thing that many cameramen would avoid. They would be afraid to trust the exposure reading they’re getting. One of the methods I employ to make sure what I’m getting is to use a spot meter and read exactly what the skin is giving back. When shooting a black picture, you find that everybody’s skin is different. In the same scene you may have several black people, some of whom have a blue-black cast to their skin, while others have a warm-brown cast. So how do you compensate for this with your light? I simply use the spot meter, which tells me exactly what I’m getting back from each face. Then I try as best I can to balance out each face to the extent that I get enough exposable light on each one, but not so much that they come into exact balance and look exactly the same, rather than the way they would look to the human eye. I don’t pound so much light into a black face that it bleaches out. Instead I let it fall underexposed, so that it takes on the deep rich tones that it should have — so that it looks very natural.

There is one sequence in the film where you have James Earl Jones sitting at a table in a bar that seems to be lit only by candlelight. How did you create that soft, natural, moody look?

I planned that scene while reading the script long before I left Hollywood. I took with me to Georgia specially-made lamps that I had built in the Universal lamp shop. Each lamp was designed to look like the typical candle with a glass envelope around it that is set in the middle of a table. Inside of this envelope I placed a quartz light. I set one of these lamps on each table, thus creating the illusion that the entire room was lit from what appeared to be candles. I then placed several layers of Tough Frost inside each of them, so that I had control of their brilliance. This enabled me, from the camera side, to tone them down so that they didn’t burn up too badly. This gave the scene its natural, but moody look.

Where do you go from here? All of your success in recent years must have changed your life — isn’t that so?

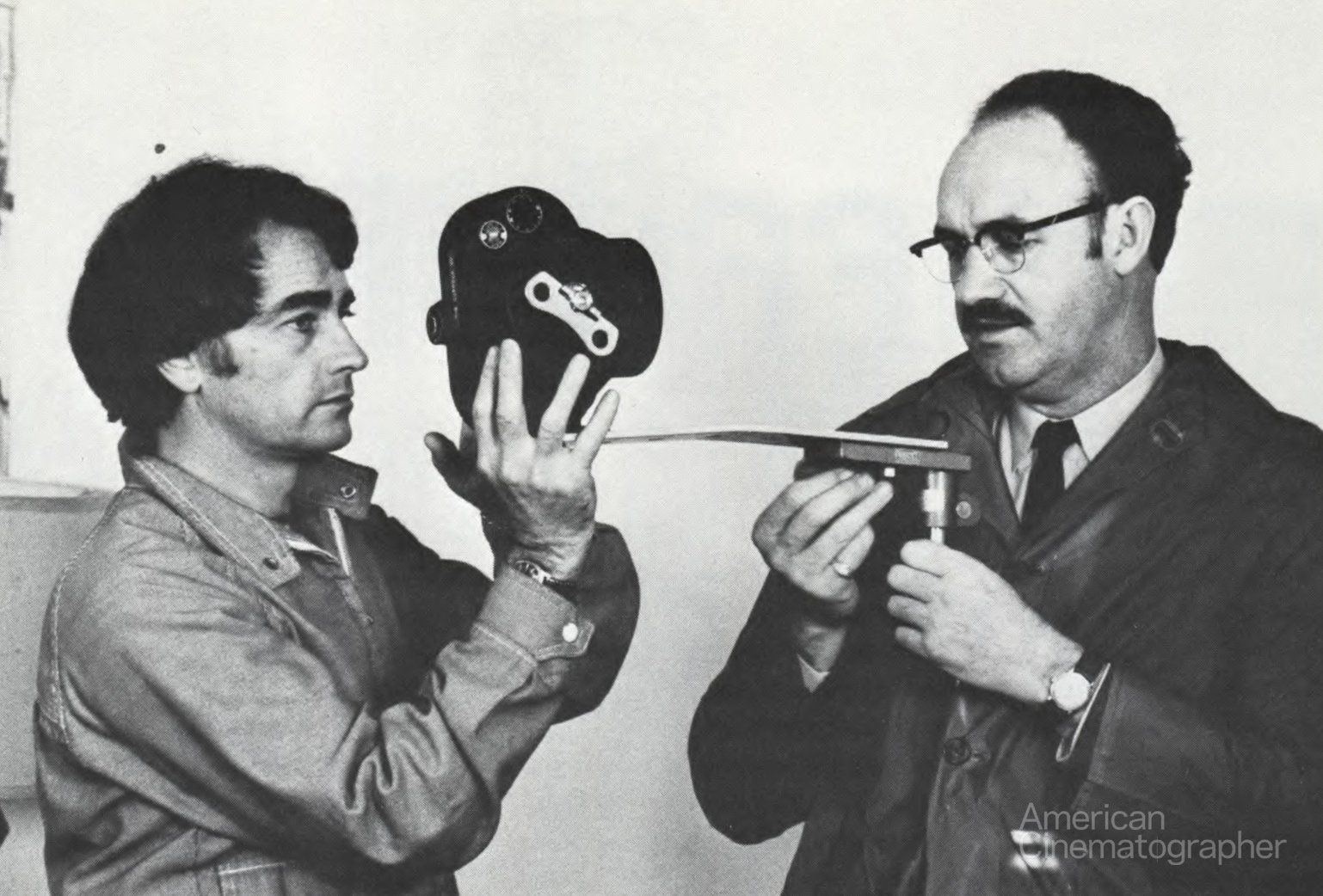

Success changes your life and must be dealt with. Fortunately, I’ve dealt with it before — I’m on my third career. Mainly, success offers you many opportunities; the trick is to opt for the things that will let you and your talent grow. I want to do a lot of things I haven’t touched yet. I want a binocular reflex finder to save cameramen’s eyes. I have in mind a revolutionary type of theater I want to build .. . scripts I’ve written, yet to be made into films . .. dreams to be made into reality...

Following this interview...

After the printing of this piece back in February of 1977, Mr. Butler went on to continue his storied career for nearly four more decades. In that time he would add work on such hits as Capricorn One, Grease, Stripes, Child's Play, Hot Shots!, Anaconda and Frailty, plus three of the Rocky films.

Additionally he would receive three Cinematography-related Emmy nominations, winning in 1977 (Raid on Entebbe) and 1984 (A Streetcar Named Desire). In 1997 he won Best Cinematography at the Stockholm Film Festival for Deceiver. And in 2003 was honored but the ASC with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

Bill Butler passed away in 2023, just two days shy of his 102nd birthday.