Art Exhibit My Hollywood Reveals A Life in Cinema

Director of photography Benoît Delhomme, AFC discusses his paintings, which offer wry insight based on years of on-set experiences.

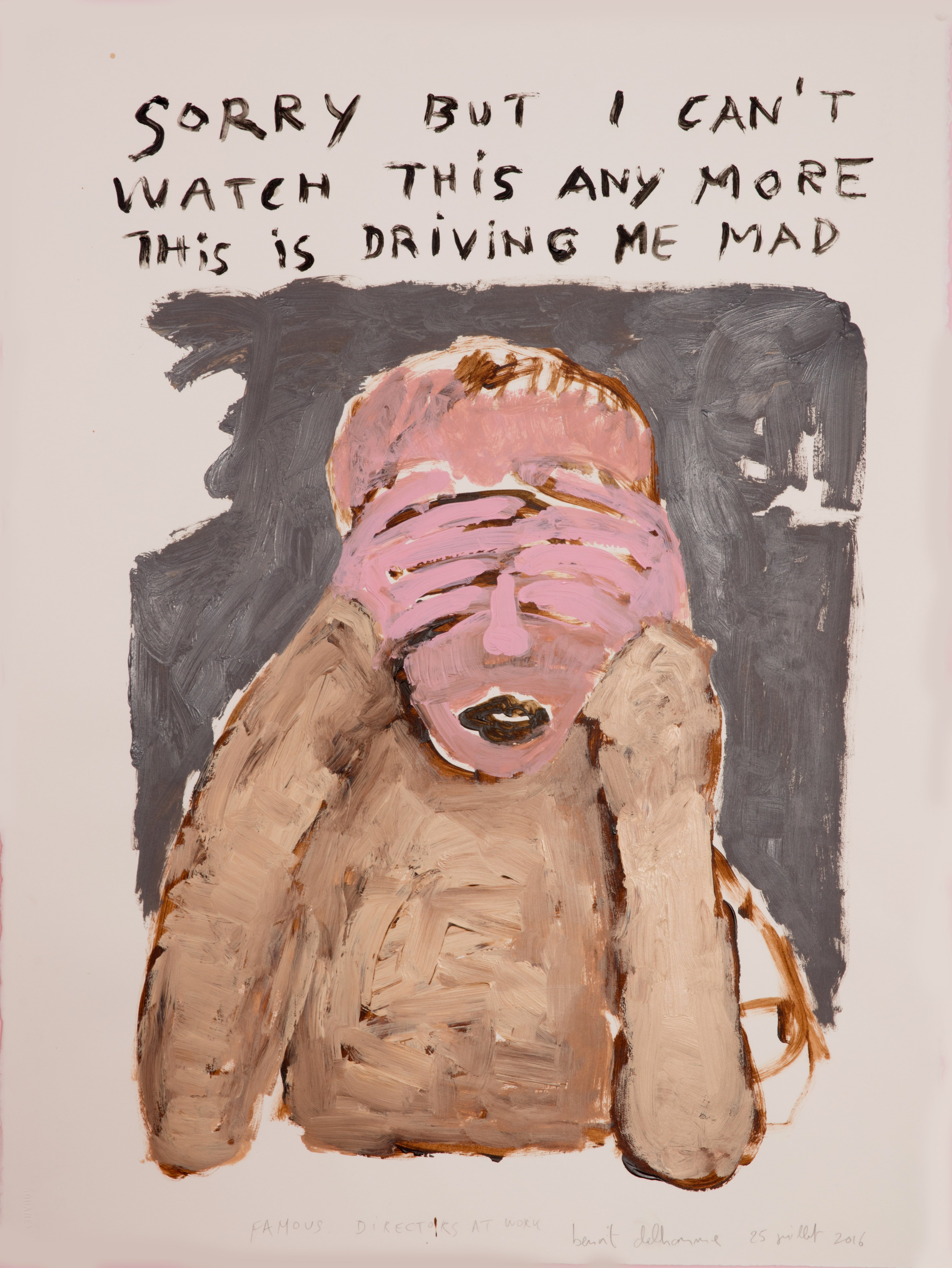

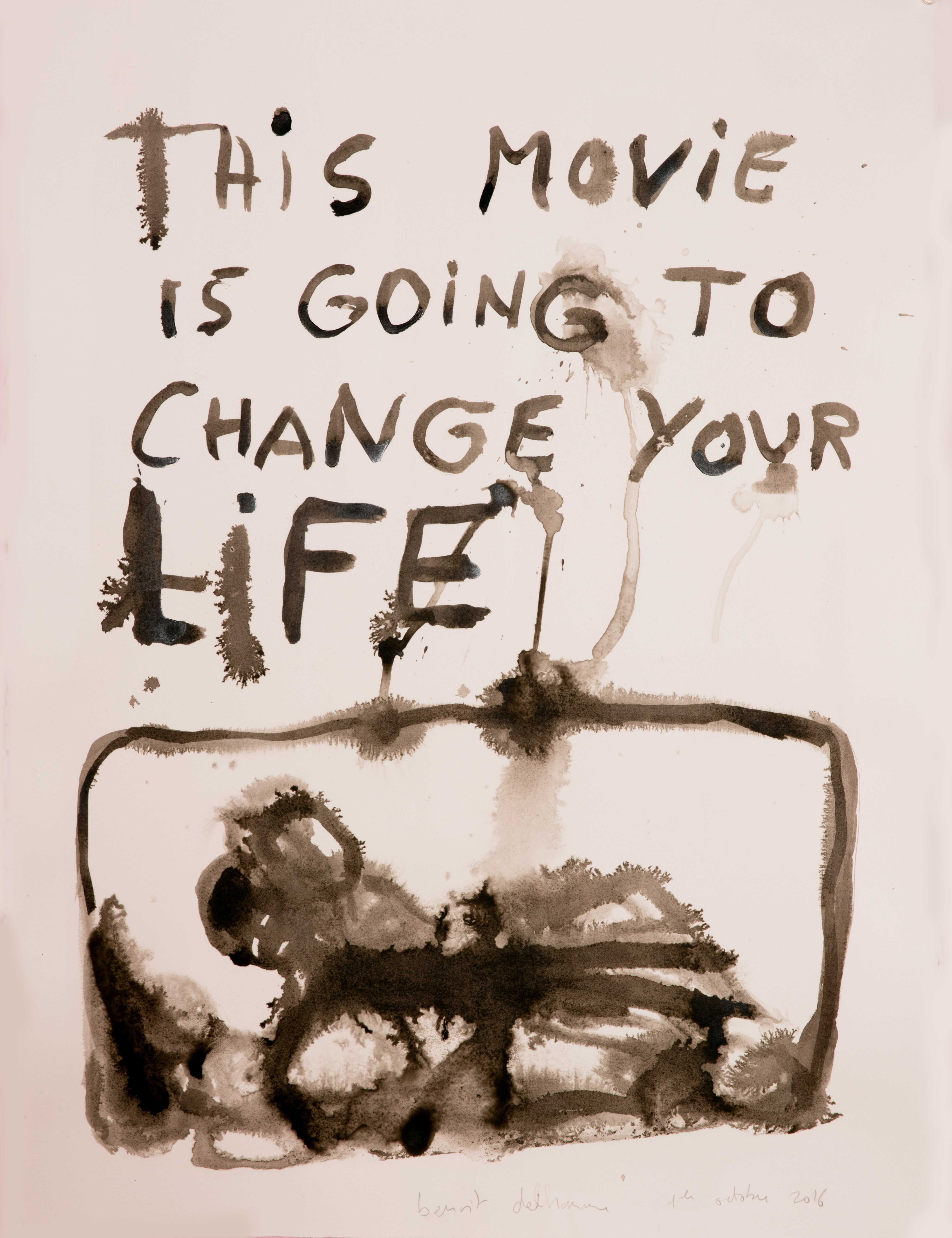

As a cinematographer, Benoît Delhomme, AFC has made a career out of exercising precision, taste, and style in his commercial work for Chanel, Tom Ford, Miss Dior, and Cartier, and with a feature CV that includes The Theory of Everything, A Most Wanted Man, and The Proposition. In 2016, Delhomme had to take a longer break than usual from his “movie life” and found himself faced with “the memories of all these years spent shooting films an sharing so much with actors, actresses and directors.” For the past 20 years, Delhomme’s love of painting ran concurrently and auxiliary to his film work, but his first solo show My Hollywood, a selection of acrylic-on-paper compositions inspired by his 35 years of working on set, represents a reversal of roles: Precision gives way to carte blanche, and the ephemeral, immediate nature of cinema is arrested.

American Cinematographer sat down with Delhomme following the opening of My Hollywood, now on display through May 6, 2017 at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York City.

American Cinematographer: What’s the impetus behind your Hollywood paintings?

Benoît Delhomme: As a DP you can’t express everything you want in a film. You have to respect the story. So, in a much more primitive way, being a painter allows me to continue a dialogue with the film in my studio.

What do you mean by “primitive”?

I want my work as a DP to be very sophisticated and sharp and I want my painting work to be the opposite — more dreamy, more poetic.

More primal, then?

The way I touch the painting with the brushes, that’s me. And on a film, you have to hide yourself. If you do a handheld shot you can show yourself. You’re following an actor and you show how you move. That’s the closest to painting in a way. The same with lighting. In cinema, people don’t want things to be too noticeable. Everything is so controlled, and in my paintings I allow myself to lose control. Some days I’ll wake up, have a cup of coffee and start to paint, and I don’t even know what I want to paint. A lot of the paintings in this series are morning paintings. It’s like showing up on set with no script.

Do you rehearse?

Sometimes I do like quick drawings in small notebooks. (Takes out a small black Moleskine and flips through it.) Sometimes it’s just sentences. Ideas of paintings, like a mini script. “You will never capture my soul.”

What’s more important to you, in terms of your painting work. Is it the words or the images?

When I read a script, that’s how I get the desire to make a film. It’s like when you read a book or poetry, and your imagination is taking off. When I did this most recent series of paintings, I started many times with words. When I wrote the sentence “Let’s forget the script”, I had the idea of an actor saying this to a director, as a way of saying, “give me more freedom,” or “let me improvise.”

“I’m shocked we make sometimes 2,000 shots in a film and not one shot belongs to us. Not one is our work. It’s incredible.”

Can you read some more of the sentences you wrote down in your book?

(Flips through the pages.) “Let’s do another take, with more freedom, says the actress.” I’m going to do a painting about that. (Continues flipping.)

But it’s not about being on a film set.

To be a good DP you need to be able to put yourself in the actor’s body, to think how they think. You need to feel for them. Being so close to the actors you, you know what they’re going to do. (Continues flipping. Stops) The other morning I wrote this phrase, “The camera is my friend, the camera is my enemy.” Some days I love the camera. Some days I hate it. This is what cinema is. Every day you start again and you never know if the magic will come. Some days on a film set you can struggle all day to make the lighting a specific style and you can’t make it, until the last shot where someone makes an accident and it’s exactly what you were looking for all day. A random touch of light. A misunderstanding. That’s all it takes. When I’m painting it happens all the time. I’ve run out of pink paint, so I find a color I never used before, and now I have a new combination.

When did you start to paint about your experience in the cinema?

Six months ago. And for 20 years I’ve been painting against my work as a cinematographer. You shoot a film and you make maybe two thousand shots in two months, but you have the feeling that no one shot will stay in people’s brains because there are too many of them. A person who’s just seen the film can even tell you which shots they prefer. If you’re lucky maybe they’ll remember one. With painting I wanted to spend more time on one image. I can start a painting, a wall-sized painting and change it and rework it for months. I can go away to shoot a feature and come back and the painting will still be on my wall, waiting for me to return. And now I’ve got the solution to finish it. I never abandon a painting. I will work on it until I find a solution. That’s the beauty of painting. You can stop time. In film you cannot work like this, you have to find the solution immediately. You can’t go far…

You can’t go deep?

Sometimes you can go deep by accident. Sometimes you can make incredible work by going super fast, without even thinking about it. It’s an industry so you have to deliver the picture on time, and the magic is not going to come every day, with every shot. With painting you have no schedule. No one asking you questions or telling you what to do. Sometimes it’s a pleasure to just play with the paint, or to just look at the raw canvas. A raw canvas is not like an empty cinema screen. The cinema screen is not a good blank page. It’s boring and white and has no texture. You want to forget it. When you have your canvas and you start to put a bit of paint on it, even one stroke can be enough. There’s a beauty in that.

What did you paint about before you started painting about your experience in the film industry?

I did many subjects over the years. My first paintings were like cave paintings. My characters were like statues without hands or feet. I had to learn how to draw a person. I did a series about immigrants in Australia and America. I was obsessed with fences, I thought fences were really beautiful. I was interested in them as the frame of a territory. I did a big series about birds as characters.

For awhile you were fairly prolific on Instagram, making animated paintings. What inspired you to dabble in that medium?

I thought it was the best thing for someone like me, a cinematographer who is making images all the tine, even when I’m not on a film set. I’ve been drawing on my iPad on airplanes, making images every day. Even when I do shoot, I’ll draw on my iPad at night. I’ve been making paintings for myself for years, and then just putting them in drawers and forgetting about them. Instagram is a new venue to show who I am. More than a DP. I love being a DP but I have more to say.

Is there anything you want to specifically say with your work?

Well, I’m shocked we make sometimes 2,000 shots in a film and not one shot belongs to us. Not one is our work. It’s incredible. This is why I’m painting, to own some images, to show that this is what I can do if you ask me to make something.

Do you feel that painting about cinema has a has a limited life span? What other subjects do you want to explore?

I can go on with this subject for awhile. I’ve been doing this job for 35 years, so I have a lot to say about it. I think cinema. It is my life.