Anora Ignites Bride War

Cinematographer Drew Daniels lends anarchic energy to Sean Baker’s romantic comedy-drama, which tracks a couple after their impulsive nuptials.

This article originally appeared in AC Dec. 2024.

All images courtesy of Neon.

In awarding Sean Baker’s Anora the Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, jury president Greta Gerwig said it “felt both new and in conversation with older forms of cinema.” That was the goal, according to director of photography Drew Daniels.

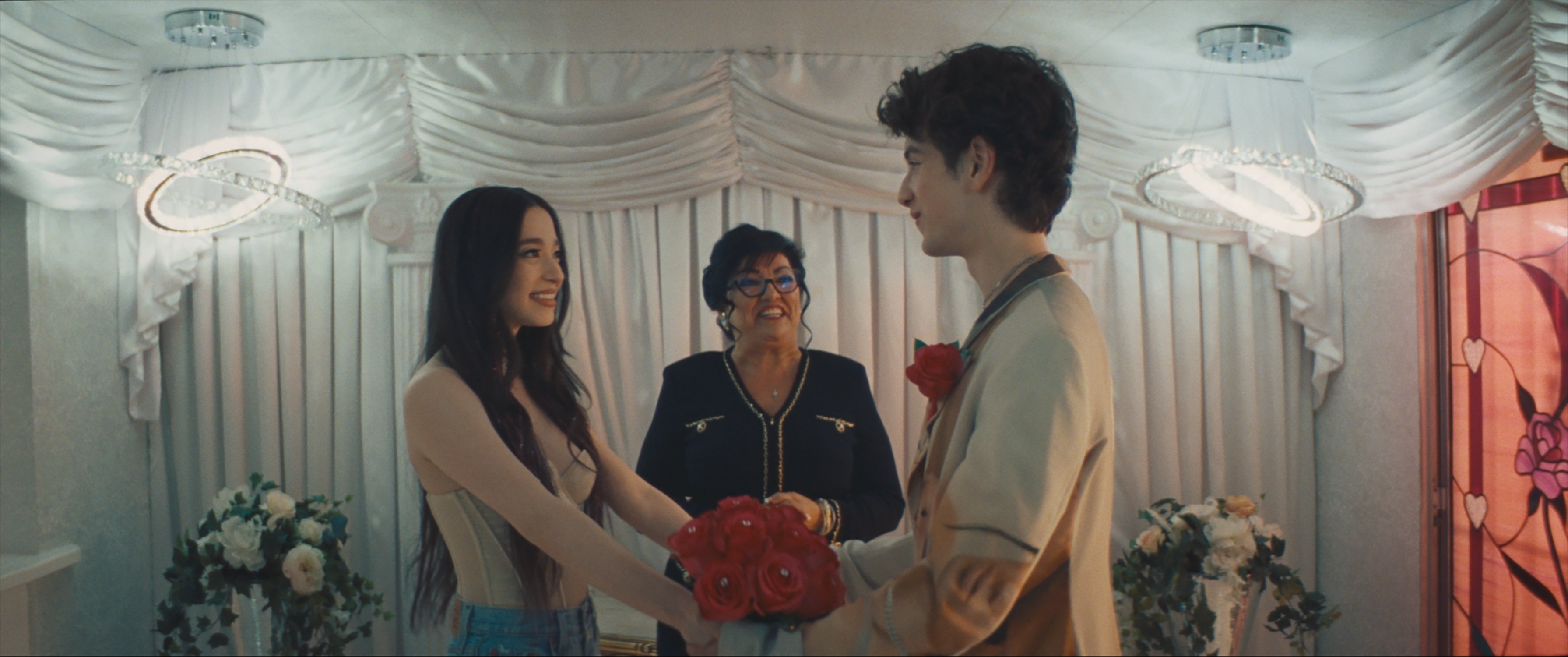

In the film, New York stripper and sex worker Ani (Mikey Madison) chases a Cinderella story when she elopes with Ivan (Mark Eydelshteyn), the immature son of a Russian oligarch. When his unhappy parents try to annul the union, Ivan flees, and his reluctant handlers pull a defiant Ani into a hapless search for him.

Anora is Baker and Daniels’ second collaboration, following Red Rocket. Daniels was named an American Cinematographer Rising Star in 2020 (AC March ’20). AC reconnected with him to discuss Anora.

American Cinematographer: Anora has a sharp, modern photographic style, but you also clearly drew inspiration from movies like The French Connection and The Taking of Pelham One Two Three [both shot by Owen Roizman, ASC] and Contempt [shot by Raoul Coutard].

Drew Daniels: Both Pelham and Contempt are anamorphic films, and the look of Pelham was the New York I wanted — fluorescents, underexposure, pushed and flashed film. They beat [the negative] up because that’s what they had to do to get exposure. Out of necessity as well as desire, that also became the look of Anora.

But it’s very subtle — it doesn’t get in the way of the story.

That’s my goal: not to show off, but to serve the film. I love this film, and I love working with Sean. We see films the same way, and neither of us wants to be showy. We like to be minimal with our coverage, holding a wide frame as much as possible. Sean doesn’t like moving the camera arbitrarily. I love that it’s all about the composition and mise-en-scène. We talk a lot about editing while we’re shooting, which helps us pare down the story and figure out what we need. [You see almost] everything we shot in the film — there’s hardly anything on the cutting-room floor.

Tell us about your prep.

Sean and I don’t spend a lot of time shot-listing in advance. Our prep process is about immersing ourselves in the environment, doing lots of scouting and meeting local people during those scouts. That opens up new avenues for locations and sometimes [leads to] casting people. The only scene we really prepped for was the home invasion at Ivan’s mansion, a 28-minute real-time sequence we shot over eight days on location in Brighton Beach. We knew we wanted the action to move from one part of the house to another, from the door to the living room, so we had a general sense of the blocking. Then, of course, on the first day of shooting, Sean rewrote the scene with the characters moving all over the house, so we had to show every corner of the set!

It was super hard. It was winter, and the huge windows had a thick tint that was equivalent to an ND .09. We couldn’t start shooting until about 8 a.m., and we lost the light around 3:30 or 4 p.m., depending on the weather. Sometimes we had sunlight, sometimes we didn’t, so we had to know when to shoot toward or away from the windows, which lined the entire set and wrapped around the house and were also reflected in massive 20-foot mirrors on both non-windowed sides of the house. We pieced it together day by day, shooting chronologically. Sean would show up every morning with rewrites, but that’s how he works: Characters evolve, performances evolve, and the film turns into something different. If we want to pivot, skip a shot one day or chase good light for a scene, we can.

How does his method dovetail with your own style?

My cinematography tends to be experiential and subjective. For instance, we wanted to see the fantasy Ani creates for her clients from Ivan’s perspective, so the scene where she dances for him at his house takes on a music-video quality, with lens flares and slick camera moves. But that’s the only time we did that. For their first time in Vegas, the idea was to seduce the audience into going along with Ivan. As Ani gets swept up in the experience, it’s reflected in the camerawork. I wanted the cinematography to reflect her as a character, both psychologically and emotionally. It needed to have attitude, scrappiness and sophistication to echo her experience in the film.

Did you operate the camera?

Yeah, I like being the person closest to the actors, almost like a barrier between the chaos behind the camera and the space in front of it. I could see it on Mikey’s face when she needed a moment, and I tried to accommodate her whenever I could. It’s a big responsibility that I think a lot of people don’t realize comes with the cinematographer’s job.

How did you treat the film stocks to get the look you wanted?

We shot on Kodak [Vision3] 500T [5219] and 200T [5213]. I really like the way tungsten renders fluorescents and existing practical lights. The green, the halation … especially when you push it, underexpose it and beat it up a bit, it just comes alive.

I needed every bit of exposure, especially in Ivan’s house. At 8 a.m., I had just enough light to shoot a stop under, so I pushed everything 1 stop for the entire home-invasion scene just to get to T2.8 1/2. Skin tones were still at least 2 stops under. To maintain a consistent look over eight days, I took a lot of notes. I’d call out spot readings to gaffer Chris Hill, like, ‘The sky’s at a 16, the faces are a stop under at 1.4 or 2'. I had notes for the door section, the living-room section, and the fireplace, where the big fight happens. At the end of our day, we would use our notes to light night-for-day shots that didn’t look toward windows. Our dailies colorist, Adam Moore at PostWorks New York, did a great job matching the shots.

For the opening shot of the movie — a tracking shot along all these lap dances, zooming into our hero — we pushed 2 stops just to get it 1½ stops underexposed. I shot it with a Square Front Lomo 40-120mm [T3.1] zoom lens at a T5.6, 48 fps, and I had to light it with Astera tubes. I thought it might turn out completely useless, grainy and muddy, but it became one of my all-time favorite shots.

For the nighttime driving scenes, I was often pushing 2 stops and lighting their faces 3 stops under, sometimes more. I wanted their faces to be so dark you could barely see them, letting the passing streetlights give them brief pops of light. We didn’t use any overhead rigs or push light into the car; we just used a set of custom-made RGD LED light pads that gaffer Chris Hill made for me on Waves to provide a subtle dashboard light that softly illuminated their faces.

Also, in addition to pushing, I sometimes used an Arri Varicon to lift the shadows a bit. I wasn’t adding any color. I dialed it to about halfway because it can get really over-the-top and milky, and I didn’t want to go that far. The Varicon is huge, so we couldn’t always have it on [the camera], but I used it a bit in the club and also in the pool hall, where we pushed 2 stops and used a Tiffen Double Fog filter. It was nerve-racking! Sometimes a shot came out too grainy or too dark. A few times I probably went too far, but in the end, I love it. It feels real.

What were the considerations that went into your lens selection?

We kind of stumbled onto the look of the film, actually. About three months before we started prep in New York, I was testing Lomo anamorphics at Arri Burbank. Shooting on Lomos was always what Sean wanted, since the film is set in Brighton Beach, a Russian immigrant community in Brooklyn.

It was a rainy day, we were in natural light, and I didn’t notice the light had gradually changed. My exposure ended up being 2, maybe 3 stops under. When we graded the test, we found a shot — done with that Lomo 40-120mm zoom — that was really underexposed, and after pulling it back up, it started to fall apart in all the right ways. It had a coolness with a slight green tint. Because it was underexposed, the blacks got muddy and plugged up, and the image was grainier than normal. I thought, that’s the look.

I shot about 90 percent of the film with two Lomo anamorphic lenses, a 35mm and a 75mm. The Round Front Lomos were T2.8 or 2.3, but I kept them at T2.8 1/2. I don’t love shooting wide open. I try to get some depth; I want to see the space, the location. In Anora, you feel Brighton Beach and you feel New York City because we composed our actors so that the environment would always be present.

If I needed to go wider, like to a T2, I used Atlas Orion anamorphic lenses. The 25mm Atlas Orion was fun — its distortion is amazing.

The rest was shot with the Lomo zoom, a beast of a lens with leather bellows on the front and a huge, square, anamorphic front element. It’s a true front-anamorphic zoom, and it’s soft, with everything tinted green because the glass is so old.

What was your goal with composition?

Our taste leans toward wide compositions. We mostly wanted a very controlled feeling. If we could do it in a static shot, we did. Simplicity was always the goal. We’d move the frame subtly to keep the characters in it, but I didn’t want to lay track all the time. In fact, we hardly used any track. Our dolly grip, Connor Bewighouse, did most of the camera moves on a Fisher 11 dolly over marble floors, carpet, whatever. For the scene where they’re looking for Ivan in the pool hall, I used the tripod rolling wheels. The floors were mostly smooth, and I could push the camera around myself with the zoom lens. I wanted that imperfection, that human touch.

You mentioned the complexity of the home-invasion sequence. How did you and Sean work out the blocking?

We shot the entire scene like a Hong Kong action film: master shot to master shot, getting the small pieces in between as needed. Our approach was very considered, grounded and focused on wide shots that held multiple characters, with camera moves that feel invisible because we’re just moving with the actors, going from one composition to another.

How did you determine when to move from sticks to the dolly, to handheld, to Steadicam?

Sometimes the energy level called for handheld, like when Ani’s bound on the couch and they’re pulling the wedding ring off her finger. That triggers something in her — desperation, fury — so we matched that energy with handheld camera moves. Once she calms down, we go back to sticks.

Sometimes we went handheld out of necessity. There’s a scene in Tatiana, a Russian restaurant in Brighton Beach, where Toros [Karren Karagulian] interrupts a karaoke party to ask about Ivan. It was available light, and I was pushing the film 2 stops with the 35mm Lomo and a 1,000-foot mag. We did it three times, and the first take was amazing. We had permission to shoot there, but those were real customers and they didn’t know what was going on, so the second time, they started getting pissed. The third time, someone tried to fight Karren, so we were done.

[Steadicam operator] Sawyer Oubre was amazing. The camera didn’t float; he moved it elegantly and instinctively from composition to composition, even in the club, surrounded by 100 extras.

A lot of the humor in the film plays out in wide shots, which follows the idea that comedy works better in a wide angle.

The wide-angle approach probably just comes from our personal tastes. We prefer to shoot wide to see the space, the actors’ body language and how they relate to the environment. It just so happens to work well for comedy, too. Plus, with anamorphic lenses — especially a 35mm — you get that distortion effect. If I’m going to shoot anamorphic, I like it wide. It just looks more cinematic to me.

And under the right circumstances, the distortion adds another layer of absurdity.

It does. But anamorphic also adds a level of sophistication, and that contrast can be funny.

Tell us about your post process.

Kodak New York processed the negative, and FotoKem did the 4K scan and the final grade and made us a 35mm print, which I’m very excited about.

We found our look early, during testing. Our finishing colorist was Alastor Arnold at FotoKem. He and I have worked together on three films now, so we have a good shorthand. He made a great dailies LUT, and Sean fell in love with it during editing. It was a cool, milky look, which was different for me — I usually like strong contrast and bold color — and we didn’t stray too far from that LUT in the final grade. We added a bit of contrast here and there, pulled out some green, but overall, it stayed very close. I wasn’t too worried about perfectly matching every shot. If you look at films like The Taking of Pelham One Two Three or The French Connection, a lot of it doesn’t match, but they still look great. I leaned into that messiness on this film. Sometimes dolly bumps, inconsistencies in grain and color, or other mistakes are what makes the film special.

How has your career path evolved since you were named one of AC’s Rising Stars?

Honestly, that put some pressure on me! But recognition like that confirms for me that I’m on the right path. I just try to follow my heart and work on things that speak to me. I’m not interested in big, flashy films; it’s the small, difficult indie projects that take you on a real journey. With such limited resources, sometimes all you have is heart, and for me, films with heart are everything.

I also try to choose projects that scare me — things I don’t know how to do or that push me out of my comfort zone. Those scary projects are often the best ones.

Anora won four Oscars at the 97th Academy Awards, including Best Director, Best Original Screenplay and Best Motion Picture.