La Divina: Maria

Ed Lachman, ASC reteams with director Pablo Larraín to explore the mindset and memories of an opera icon.

All Images courtesy of Netflix.

Pablo Larraín’s Maria offered director of photography Ed Lachman, ASC a window onto a world he’d never considered before: opera. The story follows renowned coloratura Maria Callas (Angelina Jolie) as she dwells in seclusion in Paris years after stepping away from the stage. Beset by illness, she ruminates on the past, recalling lifelong personal hardship, fading professional acclaim and rare moments of happiness.

Larraín and Lachman embarked on Maria shortly after wrapping the satirical horror film El Conde (AC Nov. ’23), which brought Lachman his third Oscar nomination and fourth ASC Award nomination. Production was based at Origo Studios in Budapest, and Lachman worked with a mostly Hungarian and German crew. Filming involved practical locations in Paris (for Paris exteriors), Athens (Aristotle Onassis’ yacht), Budapest (Paris interiors) and Milan (La Scala).

Lachman discussed Maria with AC shortly before the film had its U.S. premiere at the New York Film Festival.

American Cinematographer: What did you feel you had to learn about opera to tell this story?

Ed Lachman, ASC: I’d been to a few operas, but I’m by no means an aficionado. Pablo was my way in. What I became interested in was exploring what’s similar or dissimilar between opera and cinema, and I found there were a lot of ways I could connect the two. That was the revelation.

What were some of those parallels?

How an audience views an opera can be compared to the way an audience views a film. The audience participates with the images, and they’re also creating images from the music and text. Pablo chose an observational, reflective style of camerawork, these moving-proscenium kind of shots with wider-angle lenses, and I think that invites the audience to piece together the relationships in Maria’s world for themselves. Also, the way I used mixed color temperatures and color gels is very similar to the mannered, theatrical way opera is staged; it helps reinforce and immerse the audience in a heightened sense of light in her apartment to feel like it could be a source, but then I heighten that reality in color and contrast, making it more expressionistic, almost like a Douglas Sirk film. It’s not the neo-Gothic chiaroscuro of El Conde, but something more open, in a sense. I wanted to feel a softer, feminine palette.

The juxtaposition of warm tones in her apartment and cool ones entering the space from outside is quite pronounced.

I think of the warmer colors as her nest, her way of protecting herself against the deluge of what she experiences from the outside world. The adoration and love Maria Callas received in her public life were things she never had in her personal life, and the stage was her refuge, so when she lost her voice, I think she lost her ability to survive. I wanted an element of color to be an intrusion or invasion. When I lived in Paris, there was always a green neon light near where I was staying, and that was always in my mind. I played with green as some kind of artificial light that’s abrasive and an intrusion against her warm environment.

Was your desire to do that what led you to shoot film? In the past, you’ve noted digital’s shortcomings in terms of mixing colors in the frame.

There are a few reasons we didn’t shoot digitally. I do believe the way negative sees color is different than the way digital sees color, especially when you’re mixing colors the way I do. I think of it this way: Film is like oil paint, and digital is like watercolor in that it’s harder to mix colors. If you’re shooting in tungsten at 3,200 Kelvin and you have daylight blue coming in the window and you warm up the lights inside, you get the blue and the warm digitally separated on the sensor, but with film, those areas cross-contaminate and create a third color, and that mixture of color gives the image depth. In film, also, the grain changes in each frame with the exposure, with fine grain in the highlights and larger grain in the shadows and underexposed areas. In digital, the noise or so-called ‘grain’ is pixel-fixated electronically on a flat chip that doesn’t have the random grain structure of film or the RGB layers that display a depth between the layers, like an etching, when exposed. Some people open up to wide apertures thinking the out-of-focus digital feels like grain, but I don’t experience it that way.

Another reason we thought it was important to shoot on film was that all of the documentation of Maria Callas was shot on film, and we wanted this to look like something that could have been made about her at the time. The documentary crew that interviews her is shooting Super 16, and we shot those scenes on Super 16 with an Arri 416 [paired with a Cooke Varokinetal 10.4-52mm or 10-30mm Varopanchro zoom] as the objective camera and my own Aaton LTR as the camera you see them using. When we talked about what camera they should use, Pablo said, ‘We’ll get an Arri [16]BL,’ and I said, ‘What? In France at that time it would’ve been the Aaton LTR.’ Then I showed him a picture of Godard with an Aaton on his shoulder. [Laughs.] I took my Aaton out of storage, cleaned it, and it still ran perfectly. For all the home-movie footage, we shot Super 8 with the [Pro8mm Classic] Pro8 and the new Kodak Super 8 camera [paired with a Schneider-Kreuznach Beaulieu-Optivaron 6-66mm f/1.8 or Angénieux 8-64mm f/1.9 zoom].

Our film stocks were Kodak Vision3 50D [5203/7203], 250D [5207/7207], 500T [5219/7219] and Eastman Double-X 5222.

I love the results of shooting film, but it becomes harder and harder. We were shooting several different stocks, and I had to place orders every week, with the film trucked in from London to avoid sending it through airport scanners. There’s also the issue of dailies. Directors accustomed to getting DIT-corrected dailies immediately on set can become frustrated with the film-dailies process, where the negative goes to a post facility and is transferred and color-corrected without your eye being there. With film, you’re not always seeing what you’re getting until the cinematographer does the final color-correct. It also can be difficult to find entry-level technicians in the camera department who are trained to load film and keep camera reports and records. We were fortunate to have excellent technicians in Hungary that knew how to handle film, and a very good lab in Budapest, the National Film Institute Filmlab, to process the negative.

How did you approach the location that served as Maria’s apartment?

Everything we shot was a location or something we built in a real location, and that was an incredible turn-of-the-century apartment building in Budapest that was being renovated. It was stripped down to bare walls, and we were given access to the whole building. There was a large interior courtyard, her apartment was on one side of it, and I basically lit through her windows from across the courtyard with Arri SkyPanel Xs for her dressing room and makeup area, and from the street side of the building with Arri 18Ks. We were one of the first productions to use the SkyPanel X, and those allowed me to play with color temperature, which was great. We were in her apartment over a number of days, and to establish different times of day, we varied the lights’ position on the cranes and used gels on the 18Ks to shift the color temperature.

Using focal lengths from 15mm to 28mm on my Ultra Baltars to create an observational camera, we had to light from the exterior and over chandeliers for ambient light exposure. There was no place to hide lights inside. Sometimes I’d cluster two or four China balls above a chandelier, hoping Pablo wouldn’t go higher with the camera. [Laughs] Arri Rental is a major supplier in Budapest, and we had access to all the gear we needed because there wasn’t much production at the time because of Covid. In fact, I’ve never had so many lights! I was usually prelighting two locations.

We see her performing in a variety of venues, in addition to the opera excerpts that are staged out in the real world as she imagines them.

Yes, the number of theaters and locations we had to shoot in, and the need to stylize the looks of the different operas, made the project very ambitious. As much as I could, I worked with the house lighting in the theaters, implemented it, and bounced our lights into the ceiling to bring up the ambient light level for the audience. The hardest sequence was her performance at La Scala. It was very important to Pablo to shoot there because La Scala was so pivotal in her career, but it was incredibly expensive, and everything had to be prepped, shot and removed in four hours. We lit the stage with their stage lighting and board, with their technicians, and they let us bring in a 4,000-watt Robert Juliat Lancelot follow-spot, as well as some PAR cans that we bounced into the ceiling to bring up the ambient light level for the house. With marks on the balcony, everybody in the crew knew exactly where they would place the lights before we got in there. I shot with [T2] Cooke S4s because I didn’t know until I got in there whether I’d need the extra half stop. The [T2.3] Ultra Baltars I developed for El Conde were our main lenses; Pablo loved the way the glass looked on that film, so we stayed with them. I only used the Cookes when I needed the extra stop for the film negative, which wasn’t often. One instance is the night exterior where Maria is walking with Ferruccio [Pierfrancesco Favino] and gets into her limo. I was shooting 5219, push-processing it to [ISO] 1,000 but rating it at 500 because I wanted a dense negative for color saturation to express Paris at night in the ’70s.

How did you approach the Madame Butterfly sequence that’s staged out in the rain at dusk?

Rain was always scripted, so we created the rain. I hadn’t anticipated in the beginning that it would end up at night, but, fortunately, the night before, I decided we should have a crane with a light because of the short winter days we were in. That morning, I told production to get a crane, but I didn’t anticipate it would take all day to get a permit and drive it across town. It arrived maybe 30 minutes before it turned totally dark. In the end, the light created a dramatic scene that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. We also used the Ultra Baltars with 5219 pushed one stop.

Was the scene where the men on the Trocadéro suddenly turn and begin singing to Maria always intended to be shot in backlight?

That’s just where the sun was. [Laughs] That’s the fun thing about working with Pablo: He’s in the moment with the camera, and I’m in the moment with the camera and the light, so I try to work off of what’s there. We do a lot of research, but then we work off the moment.

How did the two of you work out camera moves? And was it a single-camera shoot?

It was. Pablo thinks in single camera. Working off a telescoping crane on El Conde really worked out timewise — you can be very agile in finding the shot — and we decided to do it again. We used a Supertechno 15 and a Scorpio 45, and the Supertechno became an advantage to us in Maria’s apartment, which was a large space. Pablo likes to move the camera. We’d discuss shots, but really, it was kind of in the moment. I had to imagine what the camera was going to do when I lit the scenes before he arrived on set. We also had a wonderful Chilean Steadicam operator, Diego Miranda, who lives in Mexico City but works around the world. There’s a considerable amount of Steadicam, but you wouldn’t necessarily notice. The black-and-white flashback where Maria meets Onassis [Haluk Bilginer] at the party was almost all Steadicam, with some crane work, and it’s seamless. Diego also filmed the Madame Butterfly scene.

Does Pablo like to rehearse?

More or less we rehearse in the scene. We might work on the physicality, like ‘Move from A to B,’ but we didn’t want to over-rehearse the scene for the actors.

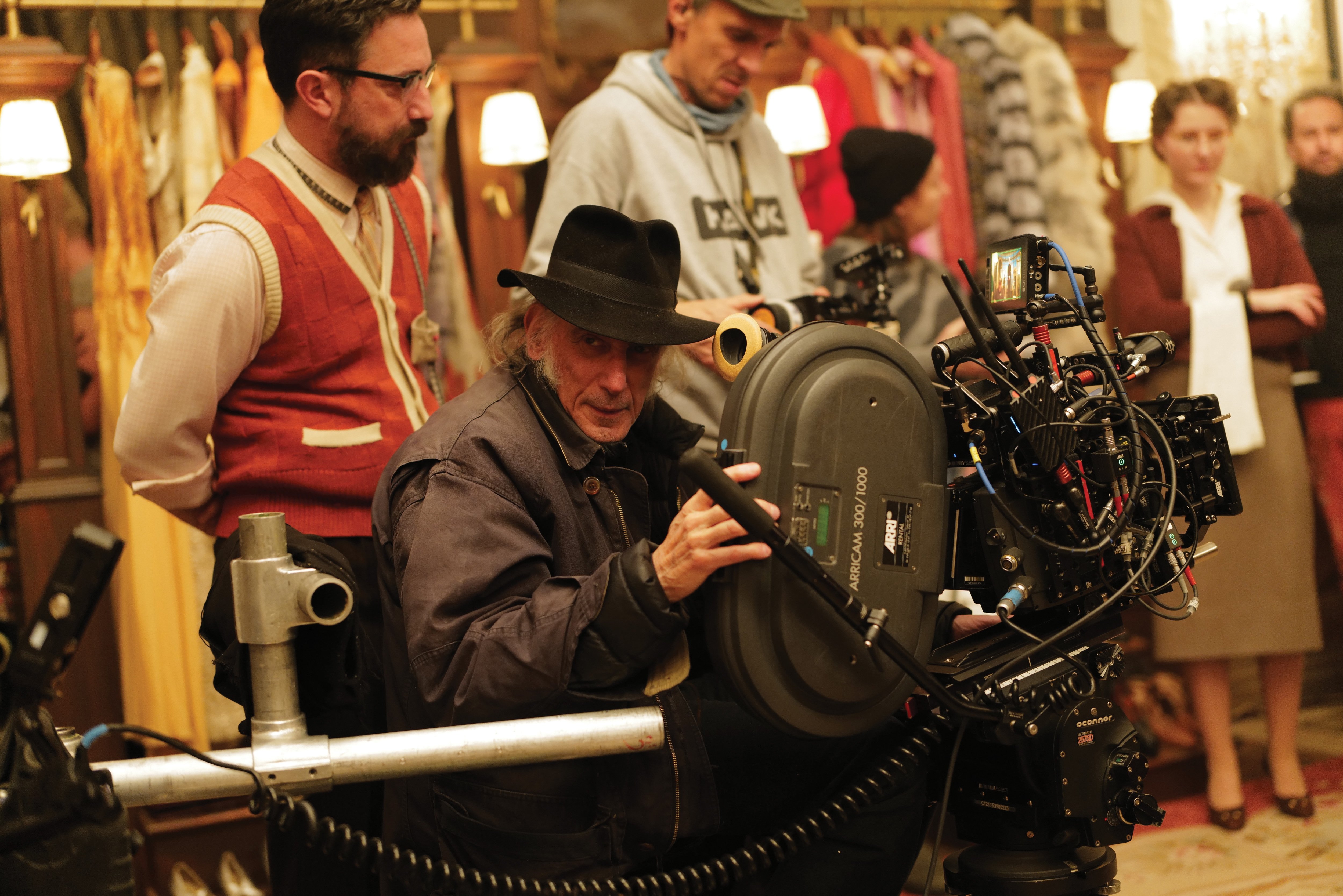

Did Pablo’s choice to operate surprise you? You did your own operating for many years.

In my career, as the films got bigger, there were more demands made on me, so I started working more with operators, who were great. Pablo studied photography, and at one point he was going to be a cinematographer. He loves operating more and more, and he has an innate talent as an operator and in setting up the shot. On this, especially because of the music and his affection for opera, I felt he had a real connection to the images. I would give him notes about a move or the rhythm with the timing. I always say images have a rhythm the way music has a rhythm, the way it moves from A to B. That’s a very personal thing. The way I feel about a move might be different than he does, but he is the director and he was my operator, so we had to work it out together. For me, operating is all-consuming — without having to direct also — so I would remind him how we could look at a scene visually even if he told me I didn’t have to. [Laughs]

Did you discuss or reference many other films about music or musical artists in prep?

I looked at several documentaries about Maria Callas’ life, and I looked at films by filmmakers who’ve used women as a catalyst for the ideas they’re expressing about society of the time: Mizoguchi, Ophüls, Sirk, Cukor, Fassbinder and Almodóvar. For camera movement, I looked at Ophüls’ Caught [shot by Lee Garmes, ASC], The Earrings of Madame de … [shot by Christian Matras]; Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits [shot by Gianni Di Venanzo, AIC]; and Visconti’s Death in Venice [shot by Pasquale De Santis]. For black-and-white, I looked at Di Venanzo’s monochrome work with Fellini and Antonioni, as well as Le Notti Bianche [shot by Giuseppe Rotunno, ASC, AIC] and Bob Fosse’s Lenny, which is brilliantly photographed by Bruce Surtees and has a freedom to it that I love.

How did you approach the theater where Maria meets with the pianist to test her voice?

That was another incredible location in Budapest, and it was complicated to light; I did most of it from the balcony level. For ambience I bounced into the ceiling with Nine-Light Mini-Brutes and PAR cans. I had 5Ks cross-lighting from the front and back of the house for an edge on their faces, and we could turn those on or off as needed. I also put Mini-Brutes in box seats over the doors on either side of the stage and painted them out later. Pablo wanted to be so wide with wider lenses, and that’s the only way I could get the light in.

From the stage, a green hallway is visible through the doorway behind her — a nice echo of your use of green as an invasive color.

It just happened that the wall there was green. [Laughs] Even if I wasn’t creating it, it was following me.

Lachman has earned ASC Award and Oscar nominations for his work in the picture. The cinematographer also sat down for this ASC Clubhouse Conversations episode, in discussion with Caleb Deschanel, ASC: