ASC Members Join “Female Gaze” Panel at Lincoln Center

The work of five ASC members was featured in this Film Society program — with Natasha Braier and Joan Churchill also participating in a live panel discussion.

The work of five ASC members was featured in this Film Society screening program — with Natasha Braier and Joan Churchill also participating in a live discussion.

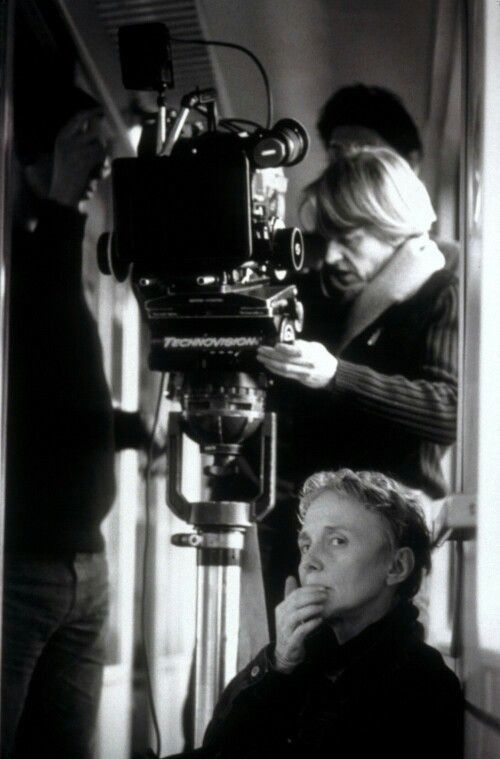

The work of 23 female cinematographers, including ASC members Natasha Braier, Joan Churchill, Ellen Kuras, Reed Morano and Rachel Morrison was spotlighted in “The Female Gaze” a two-week survey of 36 features, documentaries and shorts. Hosted by the Film Society of Lincoln Center, the event was held July 27 to August 9 in New York City.

On Saturday, July 28, Florence Almozini, associate director of programming at FSLC and one of the curators of the series, moderated a panel about the "female gaze" at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center amphitheater.

Braier, Churchill and cinematographers Ashley Connor and Agnès Godard spoke about the series and their careers and influences.

Florence Almozini: Is there a "female gaze"?

Natasha Braier: We work for a director, so our gaze is at the service of somebody else's gaze. Some male directors have very strong empathy and a very feminine gaze. Some female directors can be very masculine. So, choosing by gender doesn't make any sense for me.

Agnès Godard: I would agree. In English you have a fantastic word: cinematography. When I am on a set, it's for work, which is to be a cinematographer working with a person — a woman or man — who is a director. There is no question of gender. We should work — and that's it.

Ashley Connor: I'll bat a little bit back only because I think women as DPs have fought for equality for so long. Agnès, when I saw your work for the first time, something unlocked in me. I hadn't seen bodies shot in the way you approached them. While I won't necessarily argue for a “female gaze” or a “male gaze,” there is something that women bring. When I look at your work, and when I look at Ellen Kuras' work — women who are heroes of mine — it does unlock something emotionally in me.

Joan Churchill: My work is so different from the other women up here. I actually think there is a big difference between what a man does and the kind of access that I get and the trust that I build with people. I think women drill down and are not afraid of emotions — they have empathy. I like to work physically very close to people. I like to try to be in a kind of circle of interaction with them. Sometimes I'm shocked when I open my other eye and see how close I am. It's something you have to earn. People have to trust you. But I think guys might be shooting over the shoulder — using a longer lens. They wouldn't be trying to insinuate themselves into the heart of the interaction, which I am always trying to do. So, I do think there is a difference, at least in this kind of observational, catch-as-catch-can filmmaking.

Almozini: What inspired you to become a cinematographer?

Braier: I didn't know what a cinematographer was. I was already a still photographer and I loved movies but I hadn't put the two together. Some of my friends who were a few years older were going to film school. Through them I learned that there was something called a cinematographer, and I said, “Wow, I want to do that.”

Connor: I was a big movie lover when I grew up. I decided on a program at Ithaca College that still taught film — actual 16mm film. Very quickly I fell in love with the mechanical aspects of the camera and the control that you can have over an image.

Churchill: I'm the odd one out here because I'm a documentary person. My father had an educational film company, so I grew up with film in my life. That was the last thing I was going to do when I went to college. I was an English major. But I took this class on professional filmmaking at the UCLA film school. I had an amazing teacher, Colin Young. We all made our own films in the six-week course, and we worked on each other’s' films. I was like, “Wow, this is incredible.” I made a documentary about a used car salesman. I shot it, I edited it, and then I [thought], “What am I going to do with an English major? I don't want to teach. This would be such a great life to be able to do this to make a living.” It took me seven years to get my undergraduate degree because I then started again at film school.

Godard: It also took me a few years to go to the cinema school. My relation with image is due to the fact that my father used to take a lot of family pictures and family films. I was fascinated by that. In my small city — a village, really — there was a theater and you would go there to see a movie. So a connection was made. I dreamed to be connected with movies somehow. Of course when I told my parents, it was not to their taste. I had to go to other studies before going to cinema school.

Almozini: Was there a direction you followed to become cinematographers?

Godard: When I started, cinematography was very abstract. It was just information. You could say things with images, and that was more interesting to me. Also, being behind a still camera or movie camera was like hiding, and that was me because I was very shy. I began to learn more about films and directors when I was studying in Paris.

Churchill: When I started at film school in 1964, the cameras had just been developed in France where you could put them on your shoulders. They were ergonomic. They freed to you go and follow real life. Colin Young, the head of my film school, brought in all these amazing filmmakers, like D.A. Pennebaker and some artists from the National Film Board of Canada. They spent whatever time they could — a week or month — or in the case of James Blue, a couple of years. I never thought I could be a cameraperson. There wasn't any such thing as a camerawoman in those days. But they noticed that I could shoot and stay in focus and follow, and they encouraged me to do this.

Connor: I studied a lot of experimental film in college. The first time I saw a Maya Deren film — At Land— that opened my mind to a new way of moving with the camera that I hadn't seen before. It had a feminine energy to it. Watching that — seeing how she releases this energy — was very inspiring to me. Later, [I was inspired by the work of] Bruce Connor and Hollis Frampton. I think day one at film school we watched Lemon — which is just a five-minute shot of a lemon with a light going over it. It blew my mind — that movement of light. So, there's this kind of backbone of experimentation that I've integrated into my narrative work.

Braier: Maya Deren was an inspiration for me as well. I really didn't know much about cinema. I think it was very separate for me — the experience of movies as a spectator and the fact of making movies. I was naive, but I was also a dancer, and I think what I discovered about cinematography was the connection of those two things. Because suddenly what I was trying to capture in one single frame became a movement — a choreography. I think that once I connected that to telling stories, it was obvious that I had to do it.

Almozini: What makes you decide to accept a project?

Godard: It depends. If the script, the imagery and the subject of the script are something you are totally against, you will not do it. When you are working on a film — when you are making the image — you are taking a position. I would not be able to work on a film that says things I don't agree with. I wouldn't have the conviction. Also, you really discover a director on the set. It's not because spend two or three or four hours in a cafe. You won't meet the director until you are on the set.

Churchill: The question I ask myself is if I'm going to like myself after I finish the film. We were talking earlier about how it's good to have a family that you work with. That's what I have done my entire career. People I have worked with time and time again — Nick Broomfield, Barbara Kopple, Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker. [Pennebaker and I] did a film — Down from the Mountain — together. It was a concert at the old Ryman Auditorium in Nashville. Pennebaker said, "I'm not going to tell you what to do, we all know what we're doing." We could see each other when we were shooting. There were three of us and, I think, there were three musicians. We could keep an eye on what the other cameraperson was doing. It worked out. Nobody [ordered] us, “You shoot the close-up. You shoot the master etc.” I think I get hired because people think of me as a verite, an observational person who can follow a process and get my foot in the door and come back with the goods. I've been very lucky. Nobody's ever asked me to shoot a commercial so I've never had to decide if I wanted to do it.

Connor: I think for me scripts kind of lie to you in a lot of ways. You can read a script and it can seem like it's going to be great, and it makes a terrible movie. Or you read a script that you think is awful and it makes a great movie. Script-wise, it's also a moral issue — “Do I believe in this or do I not believe in this?” And then I 100 percent believe that you don't meet a person until you meet them on a set. And I've made plenty of mistakes. It's trusting your gut to a certain degree. Usually the films that I've done that I didn't have a great relationship on, I had red flag after red flag being thrown at me, and I was just like, “It will be okay, I'm sure everyone will be nice,” and it's not [okay]. Now I'm advancing in my career where I have more selective power. I don't have to shoot just to get a paycheck. So, I think now the questions I ask myself are: “Does this movie need to be seen by people? Does it matter? Why?” I always ask the director, “Why do you want to make this movie?” Because if they don't have an answer, it's not going to get answered the second you get on the set. They kind of have to have a reason for wanting a ton of people to work for them.

Braier: There's an element of passion that has to be really strong, it's not just that I have to agree with the material. Of course, I cannot do something that I don't agree with, but I not only have to agree, I have to feel a really strong passion about it. With the director, as much as you can know before, you only meet them on set. I'm super picky. Sometimes I don't do a film for two years. So I have to feel they have a really strong reason they have to do a film — a strong vision for the film. Because if everything goes wrong personality-wise and with the relationships on set, my passion for the story and the things in common we had for wanting to tell the story together, are what will sustain the relationship. That's what is going to keep me there if everything goes really bad. I know there's still a reason why I'm here, and I'm still going to fight for the film every day. Even if I have to fight with the director. There may be some wisdom that we have — an intuition that's very strong. I think all of us work a lot from the gut and not so much from the head.

Almozini: What kind of advice can you offer aspiring cinematographers?

Churchill: Shoot everything and never give up. Don't take “no” for an answer.

Connor: That's really great advice. When I came out of Ithaca, for me it was really helpful to find jobs that didn't creatively deplete me so that I could make money and continue shooting low, no-budget movies on the side. I babysat; I made ballet workout videos for four years; I brought a hard drive on any film shoot that wasn't paying me, and on my off days, I would be editing. When I was an AC it was really difficult to free my brain to want to go shoot on set for 12 to 14 hours more.

Braier: I think in terms of shooting, you have to be very passionate about what you are shooting and not compromise. You can say, “I'm doing this to practice coverage” or “I'm going to learn about lighting.” But that can confuse you. You're like an instrument that needs to remain in tune. Of course, it's a positive thing to get experience, but there's also the depletion of doing something that's not good. This is a very important moment to find your voice. And the more you're in alignment with who you are as an artist, the better. I shoot fewer projects, but every project represents me. That's how you keep growing as an artist. When people are seeing your work, they don't have to read between the lines. They don't have to ask, "Well who is she actually if she could have this or that opportunity?"

Almozini: Agnès, can you describe how you did the cinematography for Beau Travail, the Claire Denis film?

Godard: For me, film — especially with the camera on your shoulder — is like dancing. I try to find a good rhythm with the actors, and sometimes I add my own rhythm to their rhythm. [I do that] to be not only a witness but bring it to life — make it alive. It gives you wings when it's so well prepared. And then suddenly it's possible that you forget you have a machine — you are watching this without a machine. When you forget the machine, that's what I like. For me that's the most exciting part.

Almozini: Ashley, you just finished Madeline's Madeline for director Josephine Decker. How did you work together?

Connor: Our process is very open and free flowing. It's all pretty improvised. So for me, I'm working off intuition a lot and Josephine allows me to feel out moments from an emotional perspective. Some scenes we wanted to be textural — visceral. We wanted you to kind of fall into them. As opposed to hearing the words, you feel the words. For me, Josephine's films are really about proximity: “How close can I get to an actor and still feel their movement?” We kind of talked about dancing with a camera — I think of a pas de deux, to a certain degree. When they move, I move.

Almozini: How do you collaborate with performers?

Connor: For me, it's a lot about empathy. When working with actors it's about making a connection — some sort of feeling so you can be more in tune with them.

Godard: I think it's to inspire confidence. As a cinematographer, you cannot interfere so easily between the director and the actor. I always leave the actors to the director. If I have something to say, I will say something to the director. As a cinematographer, at the end of a sequence, the director says, "Cut." If the actor raises his head and looks at you for approval, you know he has confidence. The thing is to try to savor this confident relationship with the actors, but it has to be made very respectfully because you don’t want to [overstep] on the director.

Braier: You have this secret communication with the actor, but you are not allowed to step into directing. After "Cut," they look at you. If you're happy, it's fine. There's this unspoken language, “That was a good one.”

A related interview with Braier can be found here.

A related interview with Churchill can be found here.