Bardo, A Spiritual Migration

Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC joins director Alejandro G. Iñárritu on an existential journey with False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths.

The Tibetan concept of antarābhava, or bardo, represents a state between death and rebirth. During this transitional phase, a person’s consciousness is not connected with a physical body, so the individual may experience a range of phantasmagorical phenomena, including beautific visions or terrifying hallucinations. For some, this spiritual passage presents the danger of an unhappy reincarnation, but for others, it provides the opportunity for supreme liberation and enlightenment.

Celebrated Mexican documentarian Silverio Gama (Daniel Giménez Cacho) embarks upon this journey in Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, a mind-bending feature partially based upon director Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s reflections on his own life. The film’s narrative follows Silverio as he returns to Mexico to be honored for his career achievements — after living for years in the United States, where he’s never felt completely integrated into American society. Having spent so much time away from his homeland, though, Silverio also feels a sense of displacement there, as “a man without a country,” and the movie delves into his subconscious dreams and anxieties with a wild pageant of arresting and stylistically extravagant images.

Bardo is the first movie that Iñárritu has made in Mexico since catapulting to worldwide acclaim after his early success with the 2000 feature Amores perros, so he could relate to Silverio’s dilemma in a way that seemed “very meta” to him. “There were occasions when I met people from my past who had ideas about who I should be, or who remembered me as I was back then,” he says. “But I’m not that person anymore, because a lot of things have happened in my life since then — and maybe that version of me never really existed the way that they remember.” Iñarritu is quick to note that the second part of his film’s title — False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths — is especially important to bear in mind for anyone trying to categorize its story. “I was not interested in the precise facts [of my own experiences], or in creating a journal of my life,” he says. “I took the things that have shaped me as a human being — emotionally, psychologically, anthropologically, socially — and combined them with my reflections, dreams and fears. I also took a lot [of inspiration] from things that I’ve been reading that have affected me. So, the main character is not me, but an alter ego through which I can express myself and my points of view. The movie is how everything feels for me at this stage of my life, as I wait for the next ‘migration’ to come.

“What I love about the Alexa 65 is not the sharpness and the definition, which I couldn’t care less about; it’s more about that format’s presence. It’s very real, and very ‘bigger than life,’ and it can also become very surrealistic.”

Getting Surreal

Iñárritu’s musings and the fictional details of Silverio’s midlife crisis are blended into what the director calls “a big guacamole” of surreal sequences that unfold with the urgency of a fever dream. To achieve his grand ambitions for the film, the director surrounded himself with accomplished visual artists, including cinematographer Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC and production designer Eugenio Caballero. Khondji confirms that Iñárritu was thinking big: “One of the first things he told me was that he wanted to shoot in a larger format, which is why we chose the Arri Rental Alexa 65 as our camera. What I love about the Alexa 65 is not the sharpness and the definition, which I couldn’t care less about; it’s more about that format’s presence. It’s very real, and very ‘bigger than life,’ and it can also become very surrealistic.”

He adds, “The main thing I try to do with the Alexa 65 is to take advantage of the whole sensor. I use 95 percent of the sensor, leaving 5 percent open along the top just for safety, to accommodate boom mics or other things that might be on set. But I try not to crop the sensor. With other systems I’ve used in the past, I had to crop to 85 or 90 percent, but with the 65 I’m very adamant about shooting the sensor at 95 percent.”

Khondji notes that Iñárritu’s preference for shooting close to actors with wide lenses contributes greatly to the movie’s uncanny tone and feel: “You can go very close with the Alexa 65, but then, of course, the image starts to warp. I’m very accustomed to the camera, though, so I know how it will work with lenses of various focal lengths. I know that a 50mm lens on the Alexa 65 will render wider and bigger images, a bit like an anamorphic 50mm. You can play with the format depending on the type of lenses you use.”

On Bardo, those lenses were a set of Panavision Spheros that were specially customized by ASC associate Dan Sasaki, Panavision’s senior vice president of optical engineering and lens strategy. Khondji says he prized the lenses for their unique qualities. “They have a bit of softness,” he notes, “but they’re not so gimmicky. We mainly used a 17mm, a 21mm and a 24mm — the 17mm for all the wide landscapes, and the 24mm for close-ups.

“Alejandro loved the Alexa 65 for its scope, especially with the perspectives the lenses gave us,” Khondji adds. “He wanted to show almost 180 degrees in a given shot, so you could really see Silverio surrounded by his environments. It was about capturing the character and the world around him, almost like a virtual-reality perspective. At the beginning of the shoot, I had a bit of trouble dealing with close faces at extremely wide angles, but eventually I became very fluent in this language. If we were on the 17mm lens, I always kept the camera a little bit higher and a little further back. Otherwise, if we were getting very close to an actor’s face, I would use the 21mm or the 24mm.”

Roving Camera

Camera movement is another crucial element in the film. The viewer is constantly following Silverio and other characters as they roam through their surroundings, which often have an elastic feel due to the combination of kinetic moves, stylized lighting and exaggerated lens perspectives. The systems employed on the film included handheld camera-stabilizing rigs, cranes, dolly tracks and drones; the key crewmembers manning these various systems included A-camera operator Ari Robbins, key grip Richard Guinness Jr., dolly grip Joe Belschner and drone pilot Gabriel De La Parra.

The aim, Iñárritu says, was to lend natural-looking situations the feeling of a dream: “We were trying to create the sensation that you are in the flow of someone’s consciousness — the radical point of view you would have if you entered a person’s mind. If you demand logic from this film, you will not find it, because in a dream there is no time, so you cannot demand logic or a chronological order of facts. This film has a liquid nature, and our challenge was to navigate that path by threading the sequences together through the camera movements, lenses and lighting. We were attempting to move through time and space in a very sophisticated way. We didn’t want the movie to look freakish; we wanted it to look natural, but with the sense that things are just a bit off-kilter, because that’s how dreams are.”

A drone was used to capture the dynamic shots that bookend the film: Silverio’s shadow running, leaping and soaring over the desert. “Those shots were quite complicated, because we had to shoot at a certain time, at a certain height and in a specific kind of desert,” Khondji says. “We did clean shots of the desert, and then we did some tests shooting shadows at Churubusco Studios in Mexico City as references, to see how various shadows would look. After that, the shadow was added to the desert shots as a digital effect.”

An Immersive “Oner”

All of the filmmakers’ key strategies come together during a sequence in which Silverio and his family attend a lively celebration in Mexico honoring his career achievements. Following a screening in a local theater showcasing his documentary work, the Gamas make their way to a large Mexican nightclub. Later, in a jaw-dropping single-take shot, Silverio and his wife make their way from a balcony to the dance floor — where, surrounded by well-wishers, the entire family busts out their best moves while the crowd erupts in a joyous outburst of pride for their native son. As the scene progresses, the camera glides and swoops around the Gamas, as if guided by a magical force.

The impressive set piece was staged at a cavernous Mexican dance hall aptly called the California Dancing Club, which can accommodate up to 15,000 revelers. Iñárritu notes that there were no hidden “stitches” in this continuous take (although several shots were stitched together to create long takes elsewhere in the movie, including a TV studio walk-and-talk). “It took a really long time to prepare for the party sequence,” Iñárritu says. “The timing and the number of lights we had to bring in to show every single corner of the place, with the camera moving 360 degrees, made it very challenging to tell the whole story of that scene — [which is] about the relationships between Silverio and his wife, his daughter, his son and his friends, amid this crazy Mexican gathering filled with politics and his memories. All of that navigation required a lot of time so that everything would look interesting in the foreground, middle ground and background.”

Production designer Caballero confirms that prepping the location was a massive undertaking, involving “a huge prelight and prebuild because the real place is not nearly how it looks in the film. We brought in hundreds of mirrors to create all these strange reflections, as well as an incredible number of lights that the crew installed. We created these huge chandeliers that we could adjust up or down, and there was a lot of detail work with wood grain and this metallic look we created for the stage. It was a major set.”

To capture the intricately choreographed sequence with the fluid moves Iñárritu envisioned, Khondji and the camera team employed the Arri Trinity rig, a hybrid camera stabilizer that combines traditional mechanical stabilization with advanced active electronics that facilitate further stabilization via 32-bit ARM-based gimbal technology. The rig allows for five axes of control, and the operator can move the camera from low mode to high mode during a shot; a joystick can also be used to control a fully stabilized tilt axis, allowing the camera to look up or down. If the operator holds the post at 45 degrees and twists left or right, the camera can even peer around corners in either low or high mode.

“We did use Steadicam on this film, but we also used the Trinity throughout, because you don’t have to choose between low or high mode — you can do both in the same shot,” Khondji says. “We also used it for the desert sequences with the migrants because we wanted to follow them while showing both their faces and their feet. I learned to like the Trinity because it freed us to produce a new kind of vision.”

“It took us about two weeks to shoot the club sequence,” he adds. “We brought in a lot of lights, which we used in combination with a dimmer system and a monitor so we could orchestrate the lighting changes at various points during the single-take shot. That camera move was very, very difficult — Ari Robbins did an absolutely amazing job handling the movie’s Trinity shots. The interactive lighting was also complex, but I was assisted by my gaffer, Thorsten Kosellek; a truly incredible dimmer-board operator, Lukas Hippe; and my excellent DIT, Gabriel Kolodny, who was like a lab on set for us.”

Kosellek notes that his team in Mexico, headed by Andres Medina, spent two weeks just rigging the hall for the sequence, which featured 1,000 extras. The arsenal of lights they brought in included 600 Astera tubes (Titan, Helios and Hyperion) and 20 Astera Ax5s; 40 S60 and eight S120 Arri SkyPanels; 24 Martin Mac Vipers; two Robe BMFL FollowSpots; 20 Robe Spiiders; 10 LiteMat Spectrum 4s; 10 Digital Sputnik DS1s; 15 Chauvet Rogue R2X washes; and 50 LED PAR cans, “with completely new wiring of the house electricity so everything could run through the GrandMA2 console, operated by Lukas.”

Hopping Aboard the LED Train

The filmmakers took advantage of more new technologies — LED video panels and Arri’s tunable Orbiter LED fixture — for a sequence in which Silverio suffers a stroke while riding in a Los Angeles Metro subway car that begins filling with water. Exterior shots were done on location in L.A., and Caballero and his team built the subway car as a set piece at Churubusco Studios. The moving landscapes seen in the train’s windows were played back on LED panels positioned around the set piece, and 25 Orbiters provided the “sunlight” seen flickering through the buildings whizzing by. “I really like the quality of the Orbiter’s color,” Khondji says. “The subway sequence was the first time I’d worked with LED panels, so I was a bit nervous. We scheduled it for later in the shoot, and I called [fellow ASC member] Greig Fraser for some advice, because he is a master of this technique. He told me to beware of moiré, and to take care with where we placed the camera so we wouldn’t have issues with the perspective. I ended up loving the technology, though, and I can’t wait to use it again.”

A Radical Collaboration

Iñárritu appreciated Khondji’s willingness to embrace his unconventional ideas and the new technologies that were employed to realize his vision for the movie. “Darius was an incredible collaborator,” he says. “This film is radical, and it breaks with convention, but Darius understood my conception from our very first phone call. He helped me get everything into the frame with a spectacular and exceptional range, and with an elegance that would be difficult for anyone else.”

2.39:1

Cameras | Arri Rental Alexa 65

Lenses | Panavision Sphero (customized)

Subconscious Designs

Bardo production designer Eugenio Caballero has proven he can bring to screen the most spectacular imaginings conceived by top filmmakers. As an art director, Caballero shared an Academy Award with Pilar Revuelta for their dazzling work on Guillermo del Toro’s 2006 fantasy-infused World War II drama Pan’s Labyrinth; later, as a production designer, he shared an Oscar nomination with Barbara Enriquez for the striking environments he lent to Alfonso Cuarón’s 2018 black-and-white, semi-autobiographical Roma (2018).

Communication proved key to achieving Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s phantasmic plans for Bardo — especially since production initially began prior to the global pandemic, when neither Caballero nor cinematographer Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC were attached to the project. Following a shutdown, shooting restarted with the new department heads in place. Thankfully, Caballero attests, “Alejandro had very clear ideas about what he wanted to do with the visuals. The film was set up in Mexico, and he wanted it to have a very local flavor. We also wanted to play with colors in a vivid way, to create a palette with a lot of color saturation. The other important element was the dreamlike feeling.”

Caballero found Khondji to be “very open in his thinking, and full of positive energy.” One of the first topics they discussed was the kinds of textures and colors that would be used on set walls to help bring Iñárritu’s abstract concepts into concrete form. “Once production restarted, we began working on the hospital corridor shown early in the movie. We knew we didn’t want a flat texture on the walls — we wanted them to shine. At first, we tested a common coating we use to create that kind of shine, but Darius felt we weren’t getting the look we needed. So, we started to experiment with various techniques involving plaster and polish, and adding the color as a tint instead of a paint. It was quite an interesting process, and we went through the same kind of discussion about the corridor’s floor. As a result, that setting became a really interesting image in the movie.”

Whenever possible, Caballero prefers to work with the cinematographers on his projects as early as he can to get their input into his set designs; if that’s not feasible, he stays flexible with his planning until the director of photography arrives. “If I haven’t built the set yet, I try to leave room for ‘common creation,’” he says.

Bardo benefits aesthetically and logistically from a number of those creations. Caballero constructed the circular set for the “middle-class Mexico apartment” where Silverio lives to provide maximum flexibility for shots that would follow various characters throughout the space. “That set was an interesting puzzle,” he notes. “It was built with lots of flying walls, so we could put the camera, the lights and the crew in positions where you normally wouldn’t have them. The apartment really serves as the heart of the film because it represents everything Silverio is and aspires to be. It’s not his family’s primary home — which is in Los Angeles — but it’s a happy place, and it had to convey the political, social and artistic background of the characters.”

The designer also faced the task of filling specially constructed sets with water and sand, respectively, for hallucinatory sequences set in Silverio’s Los Angeles dwelling. “The water set was built in the studio with a shallow pool to contain the water,” he says. “Then, for the sand scene, I rebuilt the same set out in the desert in Baja, California.”

Other major sets created by Caballero and his crew included a castle tower replicating a real one at Mexico City’s historic Chapultepec Castle (where the real tower couldn’t be used during the shoot for fear of damage); a pyramid of human corpses, featuring live actors lying on a structure built onstage (and later inserted into a sequence shot in Zócalo, the main public square in Mexico City); and a massive airport-security checkpoint built from scratch.

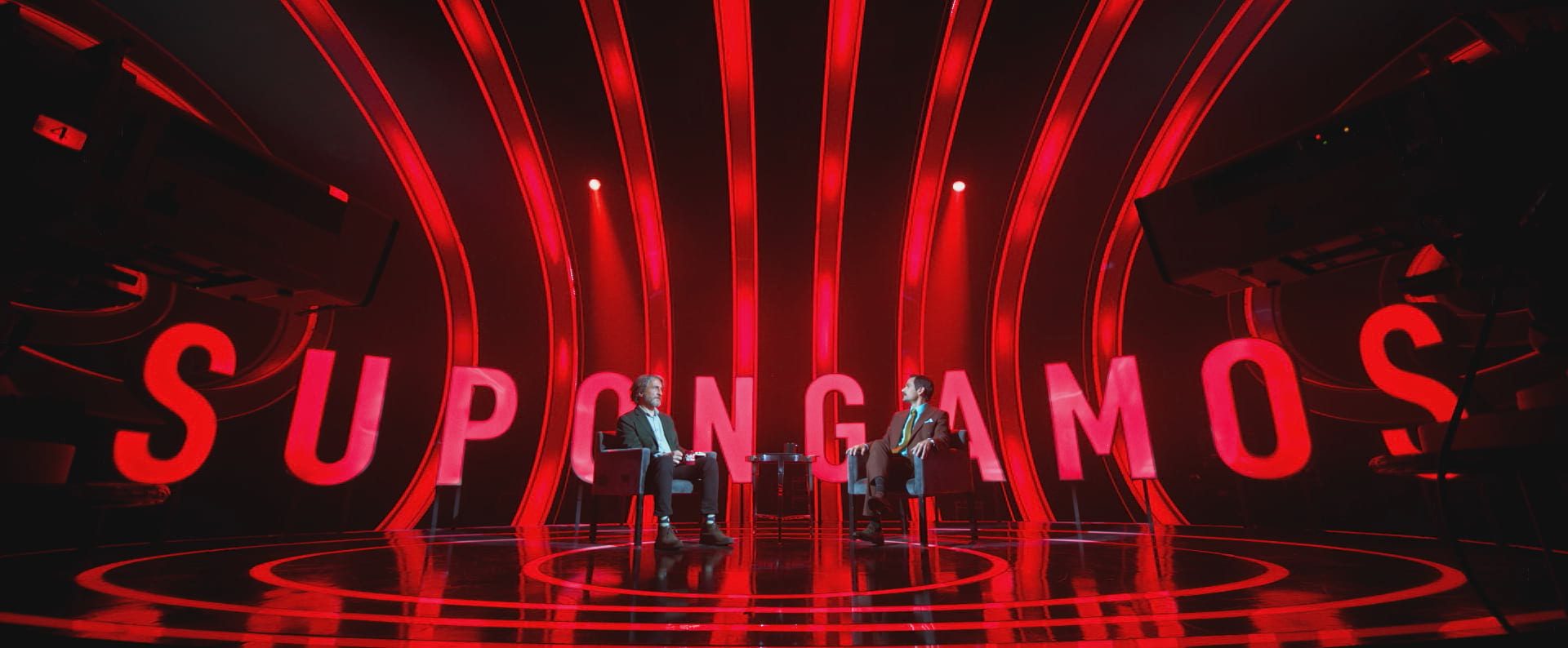

One of the movie’s most complex setups was an extended walk-and-talk that follows Silverio through a Mexican television station where he used to work — a sequence that required the filmmakers to combine parts of three soundstages into a seamless-looking sequence. The bravura set piece, which takes place entirely in Silverio’s mind, shows him being led through an area occupied by a frivolous variety show, with garishly clad performers floating in and out of frame. Then, in a sequence that follows, he walks onto a stage occupied by an intimidating newsmagazine show called Supongamos (Let’s Suppose), where Silverio imagines he’s enduring an interview he’s reluctantly promised to a resentful former colleague. The unsettling environment is made more threatening by the show’s aggressive audience members and the set’s restricted palette of what Khondji calls “cruel” red and white LED lighting, emanating from a series of large arches that form an imposing gauntlet Silverio must pass through. “Everything was wired to a dimmer console to give us complete control over the ambience,” Caballero says. “We wanted Silverio to feel really, really small — as if he was walking into these large, semi-oval set pieces that resemble giant mouths that are about to eat him.”

Khondji earned ASC and Academy Award nominations for his work in the film. He also discussed his work in the picture in this episode of ASC Clubhouse Conversations, interviewed by Caleb Deschanel, ASC: