Bergman Island: Intimacy and Artistry

Denis Lenoir, ASC, AFC, ASK details his visual approach to this romantic drama, which entailed shooting on film, naturalistic lighting, and embracing the images.

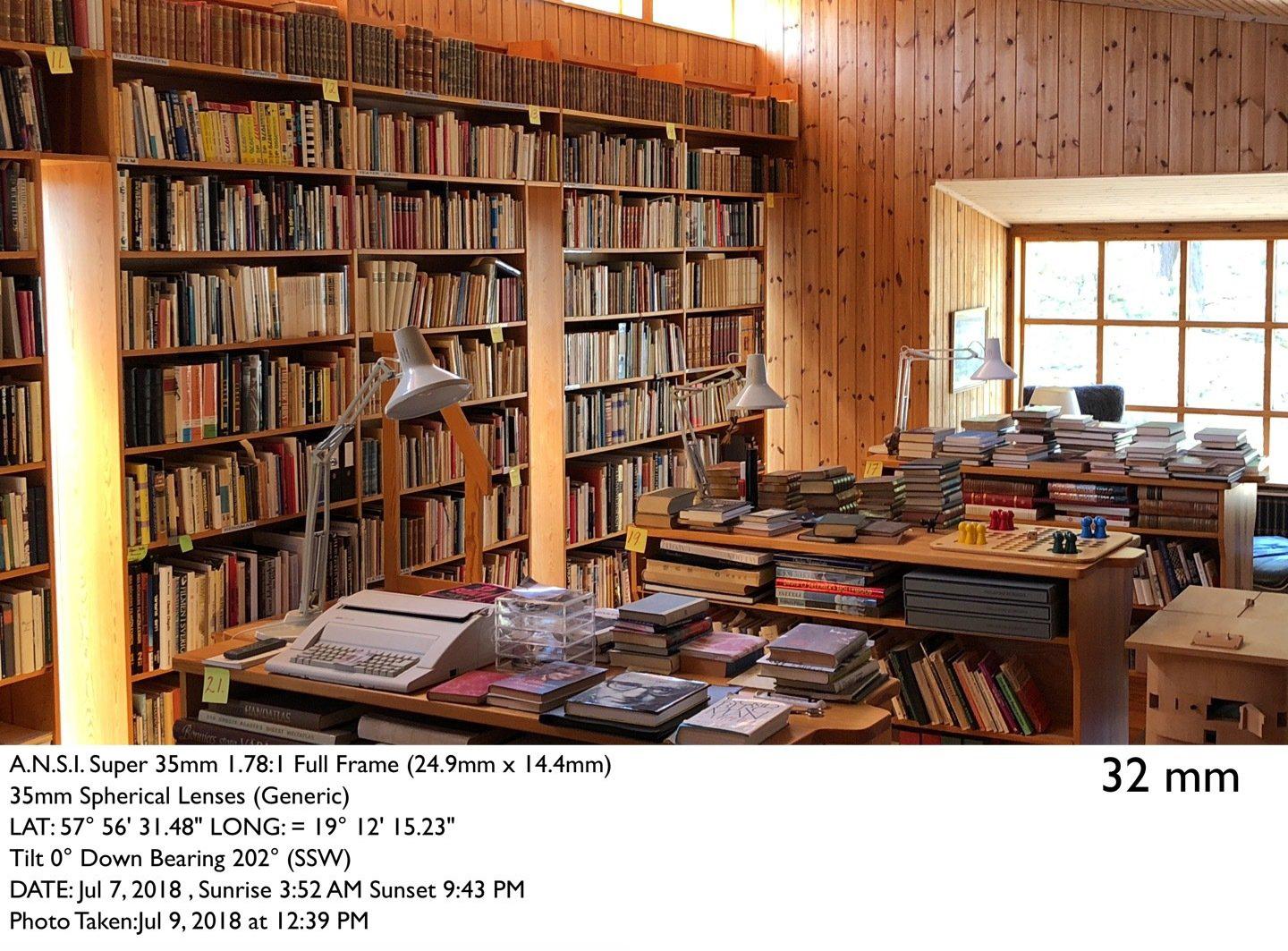

Production photos courtesy of the cinematographer

Frames courtesy of IFC Films

Editor’s note: Lenoir also kept a personal production diary while shooting and finishing this project, which contains many candid observations and can be found here.

Directed by Mia Hansen-Løve, Bergman Island takes place entirely on Fårö, the island where Ingmar Bergman shot four features, lived, died, and is buried. The film tells the story of Chris and Tony, two film directors — respectively played by Vicky Krieps and Tim Roth — who are a couple. One of them is invited to the island’s annual Bergman Week festival, and both are in the process of writing a film. As Chris describes the script she’s writing, scenes play out in the film, as if we are in her mind. In subtle ways, Bergman Island addresses the relationship — and sometimes blurs the line — between reality and fiction.

Hansen-Løve and director of photography Denis Lenoir, ASC, AFC, ASK had worked together twice before, on Eden and Things to Come. Due to the vagaries of production, they would shoot the film over the course of two summers, beginning in 2018 and completing in 2019.

American Cinematographer: What were your initial reactions to reading the script? How did you first envision the imagery?

Denis Lenoir, ASC, AFC: I first reacted as any other DP would — I was thinking how cool it was to have a film within the film, and how much fun I would have in giving them two different looks. When I started talking to Mia, she said, “No, I want them to be similar.” I was disappointed, because suddenly it was as if one of my toys was taken from me. But she was right. It’s way more interesting if you don’t know if you can slide from the reality to the fiction without showing the audience that we are changing the stage. One of the strengths of the film is that it’s not in your face. The audience has some work to do. It’s subtle.

This is your third film together, and you’re friends. How do Hansen-Løve’s working methods mesh with your approaches and techniques?

Mia goes herself to the locations ahead of time to think about it. She comes back and together with her continuity person, and they play the scenes together and take photos with their phones. They have gotten pretty good at taking photos with their phones without looking at it, as if a third person was photographing them. So that becomes a kind of storyboard. Together, they draw the blocking and create the shotlist a couple months ahead of time. Then, Mia asked me to come again, rather early, before my official prep. She used this time to show me what she’s done, which has been made properly presentable. The first thing is she wants me to know what she has in mind, and second, I’m welcome to comment and to change, which I do, but only on the margin. And then we shoot. If she manages to get the actors doing the blocking she had in mind, she applies her shot list. Eventually the actors are rehearsing, discussing, and we evolve and invent something else. She has done seven films now; she improvises perfectly well. She is so well-prepared that if she improvises on one small thing, it will certainly fit in with the rest.

You shot on film, in the widescreen, 2-perf 35mm format, a.k.a. Techniscope. How did you come to that choice?

It’s worth the hassle to be in Techniscope. The negative image [0.373" x 0.868"] is very small, but compared to Super 16, there’s a significant benefit. When Mia and I made Eden [2014], my first film with her, we shot digital, and the producer didn’t give her any choice. I’m 100 percent convinced that I can now simulate any aspect of film imagery on digital. But Mia, who has an incredible eye, doesn’t like the sharpness you get when someone crosses the frame laterally. Each image is extremely sharp due to the lack of motion blur. Since then, she prefers to shoot on film. That can be simulated in digital, but it requires a lot of calculating power. So we went with Arricam LT and Kodak Vision3 50D and 500T film stocks.

How did shooting film affect your thought process and working methods on the set?

In 2016, when I shot Things to Come with Mia, it was my first feature on film for a long time. I was reluctant to have to light for exposure. I didn’t want to go back to that stage where my first concern is building the light. But actually, little by little, I discovered that I didn’t have to expose as much as I used to when I was on film for film finish. In other words, I could work in the foot of the curve, where I would never allow myself to work years ago. I didn’t like the result if I was a little underexposed and the blacks started to become milky. Now, I can get the result I want when I’m coloring – I can bring back decent blacks and remove the grain. I confess this almost to the shame of my younger self, who I imagine asking me, “What are you doing! Are you crazy?” No, I’m not crazy. I’m using the modern tools. Now I allow myself to work in film almost the same way I work in digital, which is not caring as much about lighting for exposure. I can work as I work in digital, which is with very little light and using practicals a lot — supplementing them or correcting them.

The film feels very naturalistic, with the famous Swedish light suffusing the images. How did the lighting work with the other choices you and Hansen-Løve were making?

I’m used to working with Mia’s approach. And natural lighting is more or less what I do and what I do best. I’m convinced that I’m not making a very different image that any other DP might. My colleagues might hate me for saying this, but it’s apparent to me that any image of the movie, before anything else, is the locations, the actors, their wardrobe, their faces. The DP’s work is in there, too, but, honestly, it’s on the margin. And I can prove it, because of projects I’ve done with other DPs. We shot almost without sharing anything, and nobody can tell whose images are whose.

Do you have a personal connection with Bergman’s films? Was that in the back of your mind on this shoot?

As a very young DP, a long time ago, I had two gods — [ASC members] Sven Nykvist and Vittorio Storaro. Storaro felt out of reach. I couldn’t see myself setting a goal to do the same thing. But Nykvist — I’m not comparing myself to him, but I belong more to his family. There’s a made-for-TV film from very late in Bergman’s career called After the Rehearsal. Shot on 16mm, low-budget, with a lot of closeups, natural lighting, practicals. And to me it was a masterpiece of cinematography. I was thinking, sadly, that if I got the same lens and camera, and the same positions, et cetera, could I get the same results? Probably not. How did Sven do that? Why is it at the same time so simple and beautiful and perfect? People can do it better than me, but it is certainly my line of work, my sensibility. That’s probably why I’ve been at ease switching to digital — for years and years, I knew how to see and use natural light, and so many digital projects use natural light.

You went with Leitz Summilux-C and Fujinon Premier lenses. What’s behind that choice?

I had been systematically using the Fujinon 18–85mm T2 zoom when filming outside. I prefer primes inside, for speed and size, probably, but also for the notion that I have to think and decide, instead of just finding. Still, I find the zoom very convenient to fine-tune a frame when filming outside where an adjustment is counted in yards. At Camerimage, I asked my friend Tomaso Vergallo from Leitz which zoom he would recommend for the best match with Summilux. His answer: Fujinon Premier, adding that tests had been made and that in their opinion the Fujinon was the best possibility with their lenses. Hence my choice.

Focal lengths appear to stay in the middle of the range — in keeping with the naturalistic aesthetic?

I was surprised that the preferred lens became a 29mm. But that choice did not come from preconceived ideas or testing. Mia and I have a lot in common, including the way we choose a lens. In some way she puts someone in the frame. I put myself in the room at the distance to the action where I want to be. Knowing where we will put the camera, and knowing very intimately how much of the actor we want to see on the screen gives you the lens in some way. The lens is not chosen before. Mia doesn’t use any wide or long lenses. If we go to a 65mm, she’s feeling that it’s a telescope.

Any surprises along the way?

Mia always prefers that the exterior is not blown out. When filming Things to Come, I tried to use ND gels — as always a very frustrating experience. Knowing we would spend two weeks in a location called Damba House, and noting all the windows had the same size, I gave the dimensions to my gaffer, Dirk Van Rampelbergh, to explore the possibility of buying Perspex NDs, like the Rosco ones I had used in Chicago on a television pilot. They are very expensive, but the production had agreed to the idea. However, Dirk discovered it would take a while before they could be delivered to the island, too much time. Of course, we didn’t know that we would end up not using them for a year! But Dirk also remembered that a Belgian DP he knew who was regularly filming Angela Merkel for the BBC had noticed that the German Prime Minister had the windows of her Berlin office darkened by a local company, not at all related to the film industry and therefore way cheaper. He tracked it, got samples, tested them – two stops, almost neutral — and ordered what was needed for the house. I therefore darkened the exterior, underexposed a bit the interior, and it looks quite good!

How did you use the postproduction phase to fine-tune the images?

We had two weeks in Berlin to color time the film with Peter Bernaers at The Post Republic. The 2.9K scan was made in Brussels. On every project, I like to put some warmth in the highlights and some blue in the blacks. But this time, I discovered in the first exterior shots that the highlights were cold, almost on the cyan side, perhaps from the development. I decided not to fight it, remembering what I always say to students — go with your images, whatever they are, not against them. Also, we are in Sweden, so it’s not absurd to keep some kind of coolness, even in the summer sunlight. When Mia arrived, it became clear that she wanted an image far less contrasty than what we had quickly put together. Otherwise, she finds it too digital and fake. I understood, but I was also afraid of ending up with a flat and boring image. I tried to add some contrast in the mid-range, which wasn’t always possible or efficient. Mia also found the first exterior day shot too warm, saying it looked “like it was shot in a tropical country.” I was quite relieved to have already decided to go a cooler way and to give up my love for warm highlights. Mia and I often disagree strongly. Sometimes I’m focused on the skin tones and she cares more about the color of the grass or the sea. But the truth is we are usually talking about very small difference, nuances the audience will probably never perceive. Most directors entering the coloring process with the desire, conscious or not, to stick to the film they have given birth to in the editing room. But for me, this is the moment to discover the film that exists without us knowing it yet — away and possibly even against what I had in mind when filming, and away and possibly against the workprint they were editing with. This doesn’t mean going against the negative or the recorded data, but rather not drifting too far from the appropriate amount of contrast and color saturation once we find it.

The cinematographer also kept a personal production diary while shooting and finishing this project, which contains many candid observations and can be found here.

Lenoir was a co-founder of the AFC and has been a member of the ASC since 2001. That same year, he won an ASC Award for and earned an Emmy nomination for his outstanding camerawork in the World War II drama Uprising.