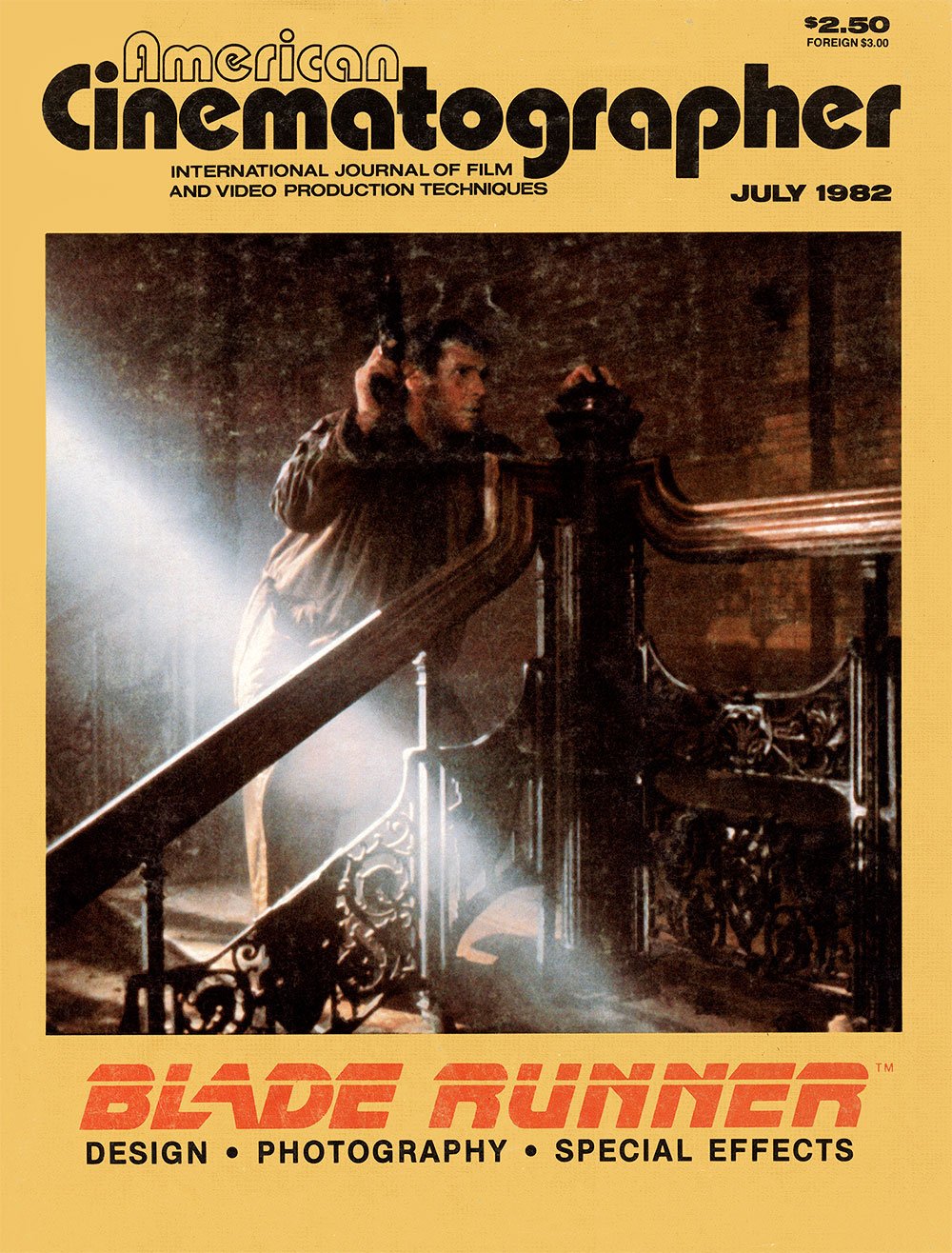

Blade Runner: Cronenweth’s Photography

The director of photography works to achieve the classical noir look Ridley Scott wanted for his futuristic sci-fi masterpiece.

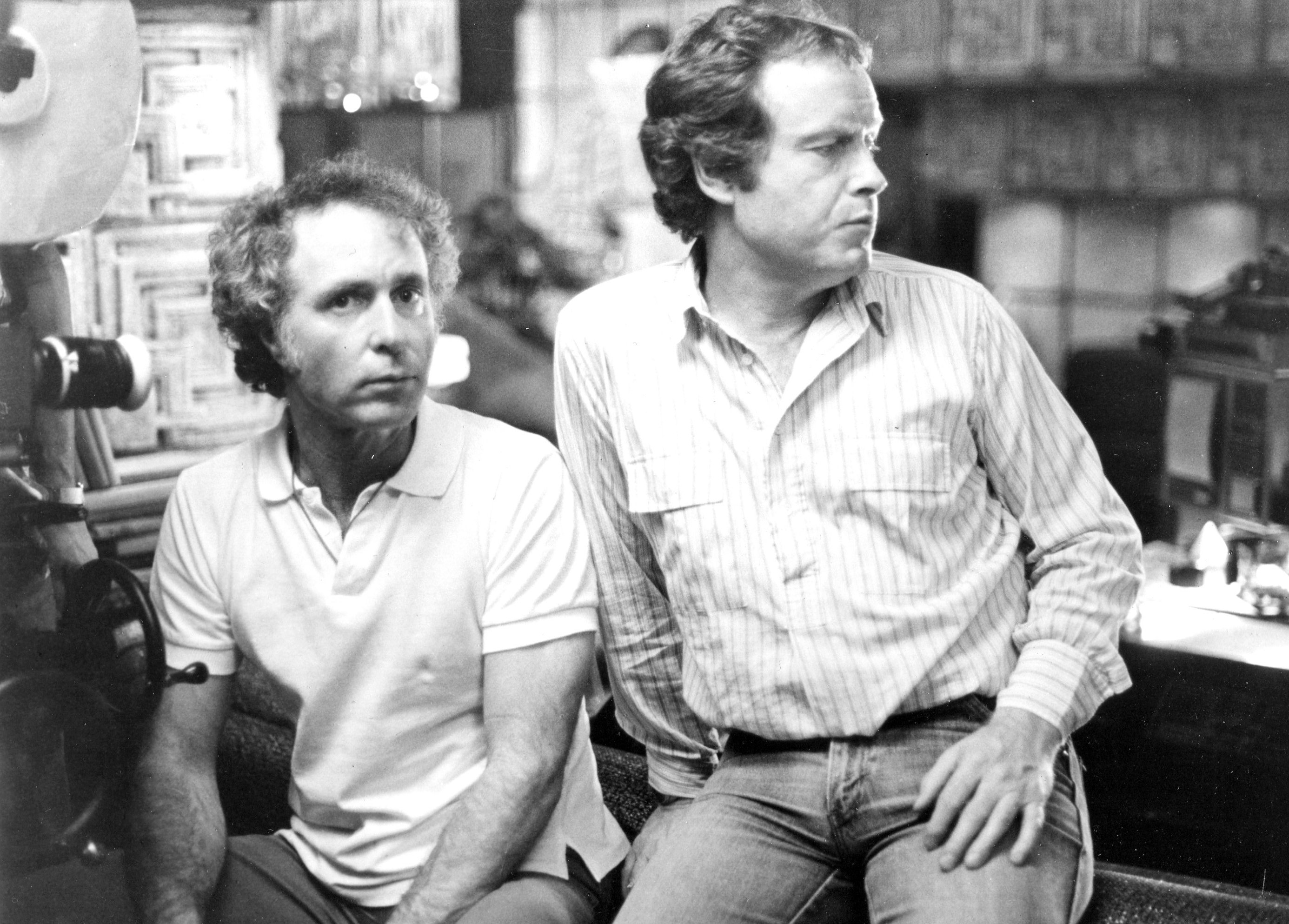

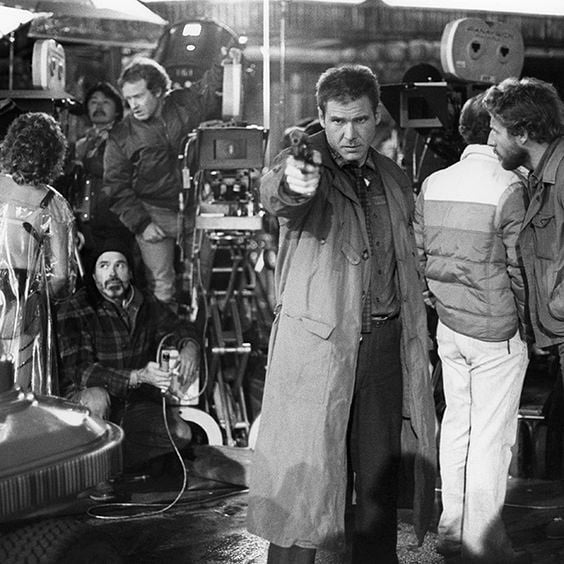

By Herb A. Lightman and Richard Patterson

Unit photography by Stephen Vaughan

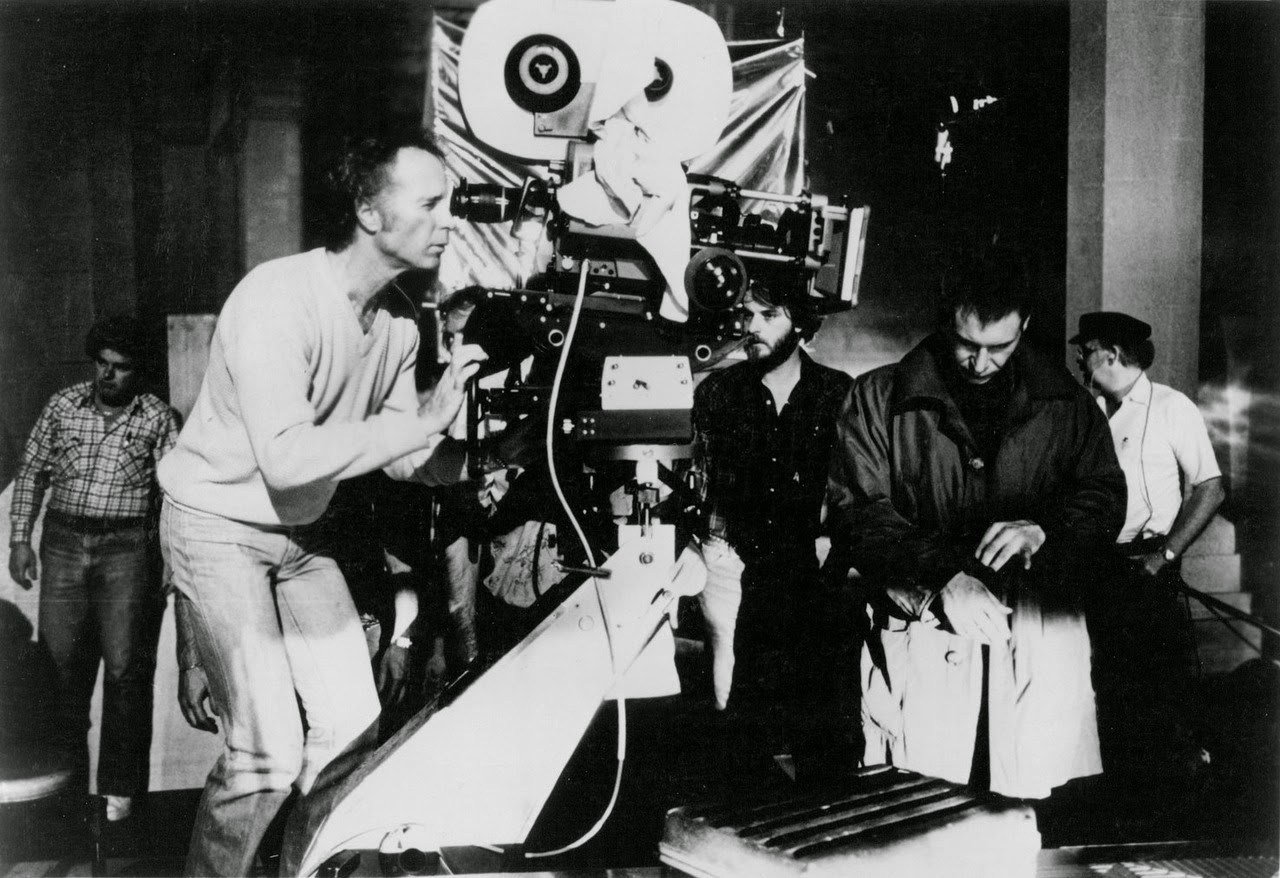

Jordan Cronenweth, ASC’s photography for Blade Runner, with its strong shafts of light and use of backlighting, immediately evokes images from classic black-and-white movies, and it is no accident that it does. As Cronenweth explains, “Ridley felt the style of photography in Citizen Kane most closely approached the look he wanted for Blade Runner. This included, among other things, high contrast, unusual camera angles and the use of shafts of light.”

David Dryer, one of the special effects supervisors, worked with black-and-white prints of most scenes in the film for one reason or another, and he almost wishes the film could be released in black-and-white. He thinks it seems to have even more depth and style in black-and-white. Needless to say this would not do justice to Cronenweth’s work, but it is an indication of the way in which the photographic style of the film harks back to classic movies. Like every other aspect of the film Cronenweth’s photography takes the classic conventions one step further, and not the least of his tools in doing this is the use of color or even the absence of color where it might normally be expected.

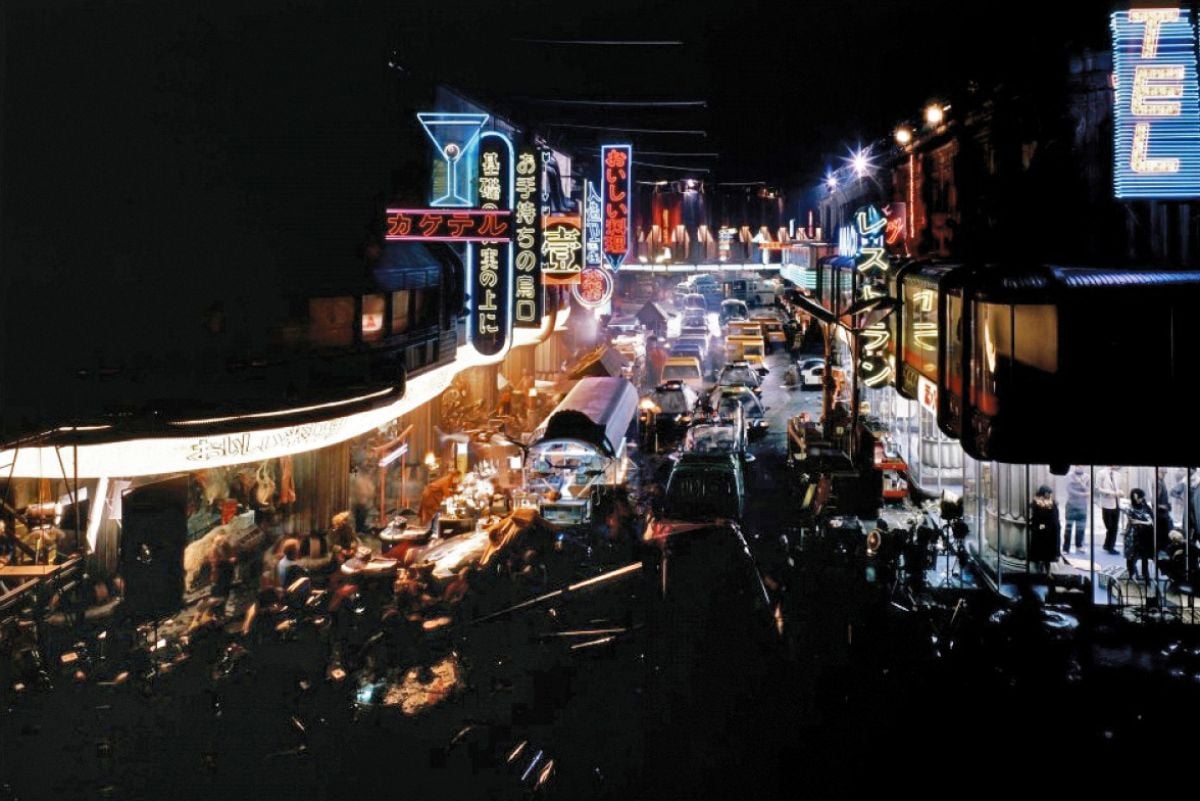

“We used contrast, backlight, smoke, rain and lightning to give the film its personality and moods. The streets were depicted as terribly overcrowded, giving the audience a future time frame to relate to. We had street scenes just packed with people... like ants. So we made them look like ants — all the same. They were all the same in the sense that they were all part of the flow. It was like going in circles... like going nowhere. Photographically, we kept them rather colorless.”

“Blade Runner is a piece that calls for extremes. It’s naturally a wonderful vehicle for this kind of lighting. It’s theatrical, but it will be very real in the film.”

— Jordan Cronenweth, ASC

If the people on the streets were colorless, the New York Street set [on the Warner Bros. lot] was anything but: “The character and consequently the lighting of the New York Street was achieved through the use of dozens of neon signs. We rented a number of them from One From The Heart. In order to achieve a photographic reality, the on-camera neons were often on dimmers set at a level just above where they would start to flicker. At the same time the off-camera neons were used as the primary source of light whenever possible by leaving them at their brightest level.”

“When the existing neons weren't sufficient for either illumination or dressing, we would simply create new ones on the spot and place them wherever we wanted. An example of this was placing letters on the side and strips on the interior of a bus that Harrison runs through in one scene. At one point we had a seven-man crew doing nothing but overseeing the neon signs. There were many more neons than there were dimmers, so we had to rob Peter to pay Paul at various times.”

Cronenweth would supplement the neons on occasion: “What you needed was some accent lighting to make the range stand out, to glisten the street if necessary and to highlight objects or people. Lighting the set was a simple matter of using backlight in conjunction with the ambient light.”

The neon lights were bright enough in one instance to enable Cronenweth to do some high-speed photography: “In the sequence in which Harrison Ford is chasing Joanna Cassidy’s ‘Snake Lady,’ the script calls for her to run through the plate glass windows of a store. The art director built a storefront situation appropriate to the action, but when it came to dressing it Ridley was very unhappy with the first attempt. They tore all the dressing out and a week later presented a new interpretation, but he still hated it. Ridley himself finally had the wonderful idea of taking the neon signs off the New York Street set and placing them in the windows of the stores. What developed was something that really worked. We then photographed the chase with multiple cameras running at various frame rates — normal and above normal. We had to deal with a pulsing effect which doesn’t occur when photographing neons at normal camera speeds, but definitely occurs at higher frame rates. We lived with it by using the pulsing as an element of the chase.”

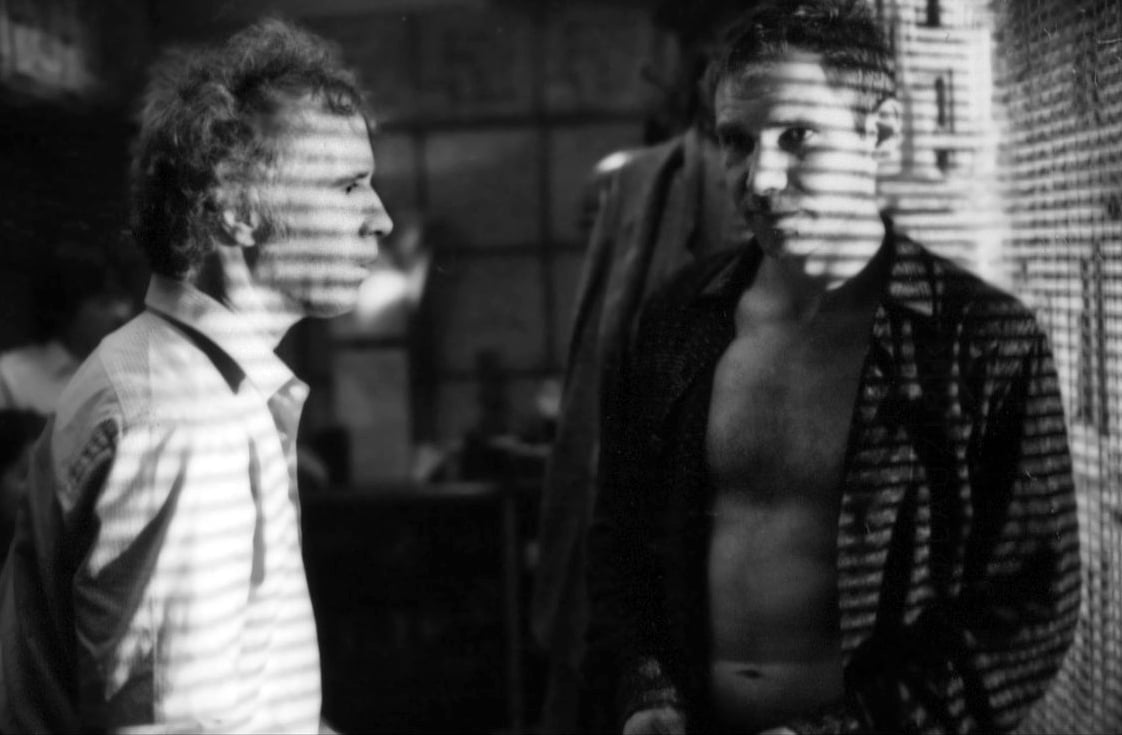

Another striking use of colored light is the scene in the toy room where Deckard encounters Pris, one of the replicants. She is made up with white make-up, and the scene is lit with rose colored light. Colored lights were also used occasionally for the light effect in the replicants’ eyes: “One of the identifying characteristics of replicants is a strange glowing quality of the eyes. To achieve this effect, we’d use a two-way mirror — 50% transmission, 50% transmission, 50% reflection — placed in front of the lens at a 45 degree angle. Then we’d project a light into the mirror so that it would be reflected into the eyes of the subject along the optical axis of the lens. Sometimes we'd use very subtle colored gels to add color to the eyes. Often, we’d photograph a scene with and without this effect, for Ridley to have the option of when he’d use it.”

“I can never use enough backlighting. It’s just that some directors want to see the face. I keep telling them that the audience only goes to see the sex.”

In discussing the photography of Blade Runner, however, Cronenweth emphasizes that technique per se is not the most important consideration: “The thing that was unique was not the equipment or the gels or the intensity or the hard or soft light. It was the concepts behind each situation telling the story. Since the film is set in the future, unusual sources of light could be used where one would not accept them in a contemporary setting. For example many umbrellas carried had fluorescent tubes incorporated in their shafts providing a light source which could create a glow in the faces of the carriers.”

Cronenweth is particularly emphatic about backlight and contrast. “I can never use enough backlighting. It’s just that some directors want to see the face. I keep telling them that the audience only goes to see the sex.”

Cronenweth is as interested in creating a mood or an effect as he is in lighting an actor’s face. He tends to use soft frontlight with a hard backlight, although he says, “I love a hard light in the face if it is overexposed. I think that’s beautiful. It’s different; it’s unusual. It’s exciting; it’s violent.

“Blade Runner is a piece that calls for extremes. It’s naturally a wonderful vehicle for this kind of lighting. It’s theatrical, but it will be very real in the film. In this film I think you’ll just accept it. It transcends theatricality.”

In addition to using soft frontlight, Cronenweth often lit faces from below. In addition to the glowing umbrella handles he made use of water or reflective surfaces to provide uplight in several scenes. The combination of warm soft uplight in the foreground with hard backlight and smoke in the background is probably the most characteristic feature of the lighting style for Blade Runner.

“Naturally, to get shafts of light one must have some medium, which necessitated the use of smoke. The story lent itself very well to it, in the context of a highly polluted environment.”

The other key ingredient in the photography of Blade Runner is the use of shafts of light. “The shafts of light was an idea that both Ridley and I had happened upon independently and had talked about. We shared that concept, and it became one of the major themes of the film photographically. We used it over and over again in different applications. One way we justified the constant presence of shafts of light was to invent airships floating through the night with enormously powerful beams emerging from their undersides. In the futuristic environment they bathe the city in constantly swinging lights. They were supposedly used for both advertising and crime control, much the way a prison is monitored by moving search lights. The shafts of light represent invasion of privacy by a supervising force, a form of control. You are never sure who it is; but even in the darkened seclusion of your home, unless you pull your shades down, you are going to be disturbed at one time or another.”

“After many tests with various units, gaffer Dick Hart came up with the most effective light to do the job. That was a Xenon spotlight commonly used for night advertising and sports events. This concept gave us some wonderful opportunities. For example there’s a late night scene in Harrison Ford’s apartment kitchen, played with the lights out. Harrison has just had a hell of a struggle with one of the replicants. Having barely survived, he is now standing near the refrigerator which has a clear plastic door. The only light in the room is from the refrigerator. Sean Young is standing by the sink, which has a window above it. She is illuminated by a soft back light through the window and by the last traces of light filtering across the room from the refrigerator. Occasionally one of the beams of light cuts through the sink windows and glows the room just enough to read Sean’s face.”

“Naturally,” Cronenweth continues, “to get shafts of light one must have some medium, which necessitated the use of smoke. The story lent itself very well to it, in the context of a highly polluted environment. It was very interesting to work with this constant atmosphere. Smoke is wonderful photographically, but not without its problems. It’s hard to control, mainly due to drafts; and a lot of people find it objectionable to work in. Beyond this, it’s important to keep the smoke level density constant, as a very subtle change in this density can result in dramatic changes in contrast. The only practical way to judge smoke density is by eye. I find that a good density is just before I lose consciousness.”

In situations where smoke wasn’t used as heavily, Cronenweth wanted to maintain the same texture; and he accomplished this by using low-contrast filters: “We changed the filters in conjunction with the angle of light and density of smoke. The stronger the backlight, the lighter the filter.”

Cronenweth particularly enjoyed photographing Sean Young, the leading lady in Blade Runner. “Sean has wonderful light, creamy, highly reflective skin, among other beautiful features. She also wore her hair up for a good part of the picture, enabling me to light her neck with hard backlight while lighting her face with soft frontlight. My favorite close-up in the film is the shot of Sean in the Voight-Kampff interview. She is holding a cigarette in her right hand, and the key light was at such an angle so as to strike only her hair, neck, hand and the smoke of the cigarette.”

All of the sets for Blade Runner had ceilings in them, and some were built very low to enhance the feeling of containment, a motif particularly well suited to the anamorphic format. “We had to light from the floor or through the windows. There’s a lot of night photography lit through windows. The sources would vary. They could be anything including searchlights, signs, direct light, indirect light, colored light, or lightning. In Harrison Ford’s apartment, we created zones of light that illuminated automatically when one walked in at different levels — an energy saving device of the future perhaps. As the depths of the apartment were penetrated, more lights went on until finally the entire place was illuminated. This effect was mostly lost, however, in the final cut.” [Ed. Referring here to the original 1982 theatrical cut, not the director's “Final Cut” that would be released in 2007.]

Perhaps the most interesting set was Dr. Eldon Tyrell’s vast office. According to Cronenweth, “It was one of the most exciting to work in. It was very large — approximately 60 feet long by 30 feet wide-with three huge windows along one side and structural ceiling supports rising from a shiny black marble floor. The walls were gray cement and the room was virtually colorless.

“The scene called for the room to be illuminated by sunrise. Outside the windows, we had a front-projection screen upon which was projected an 8" by 10" plate of the futuristic city at sunrise that [visual effects supervisor] Doug Trumbull created. This enabled us to photograph the players walking in front of the lower part of the screen and gave Doug an opportunity to later create a background with movement in it for the upper portions of the screen area. We had to coordinate the color of the set to match the color of Doug's sunrise. Sunlight was created through the use of arcs outside the windows and amber gels.

“At a certain point in the scene, Tyrell, in order to reduce the light level in the room for a test, presses a button causing enormous tinted shades to descend over the windows. The ‘shades’ were actually put in later optically; however the effect of the shades being lowered had to be created while photographing the scene. To accomplish this, Carey Griffith, the key grip, built a rig that would allow a very large 60 neutral-density filter to slide down over the six arcs being used to simulate sunlight.”

The set for Tyrell’s office was also redressed to serve as two other sets. It was used for Tyrell’s bedroom, which was photographed in flickering firelight; and as the Tyrell Corporation interview room, which was photographed in bright white shafts of daylight. According to Cronenweth, "It looks totally different in each situation, and yet it's the same set. The flickering for the firelight was created by arcs through torn strips of silk and dubotine — torn strips of silk for transmission and torn strips of dubotine for shadows.”

The most unusual set for the film was the “Ice Room,” which was built in a meat storage locker in order to create the effect of a refrigerated genetic engineering laboratory. The ceilings were repeatedly hosed down with water for five days to form icicles, and then the crew shot for two days at 7°F below zero while it was 98°F outside.

Cronenweth started out using carbon arcs to light the set, but soon discovered that they were using more oxygen than was coming into the room except when the door was open. The air began getting bad enough to necessitate changing to HMI lights. The set had translucent walls along one side so that it was possible for Cronenweth to light the scene through the walls. He added a small measure of smoke to complement the effect of cold breath.

Another interesting photographic problem on Blade Runner was shooting the interiors of the Spinners in order to create the illusion of movement. The Spinner was capable of moving in any direction and traveling at very high speeds. Cronenweth explains his approach: “In order to create a sense of the vehicle traveling at night, we used several techniques. We built two sets of programmable strip lights, each about eight feet long and each containing twelve photofloods wired individually and dyed different colors. We placed them on the exterior of each side of the Spinner cockpit.

“The bulbs were then flashed at assorted intervals in conjunction with each other and individually. Additional movement was created with set lights activated by a keyboard, so the lights were literally ‘played.’ Moving the camera on both axes by using double gear heads and using wind, water and smoke enhanced the illusion. To create additional movement for day scenes, we’d use clear globes in the strip lights and a moving arc mounted on a Chapman crane to simulate a change in the Spinner’s position relative to the sun.”

Although most of the picture was shot on a stage there were some notable Los Angeles landmarks used as locations. The exterior of Deckard’s apartment is Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House, designed in 1924 in a Mayan block motif. The Bradbury Building, designed by George Wyman in 1893, is used for the final showdown, as well as for a scene in which Sebastian takes Pris to his apartment. The downtown Pan Am building is used for a scene in which Deckard and Gaff search Leon's hotel room for clues.

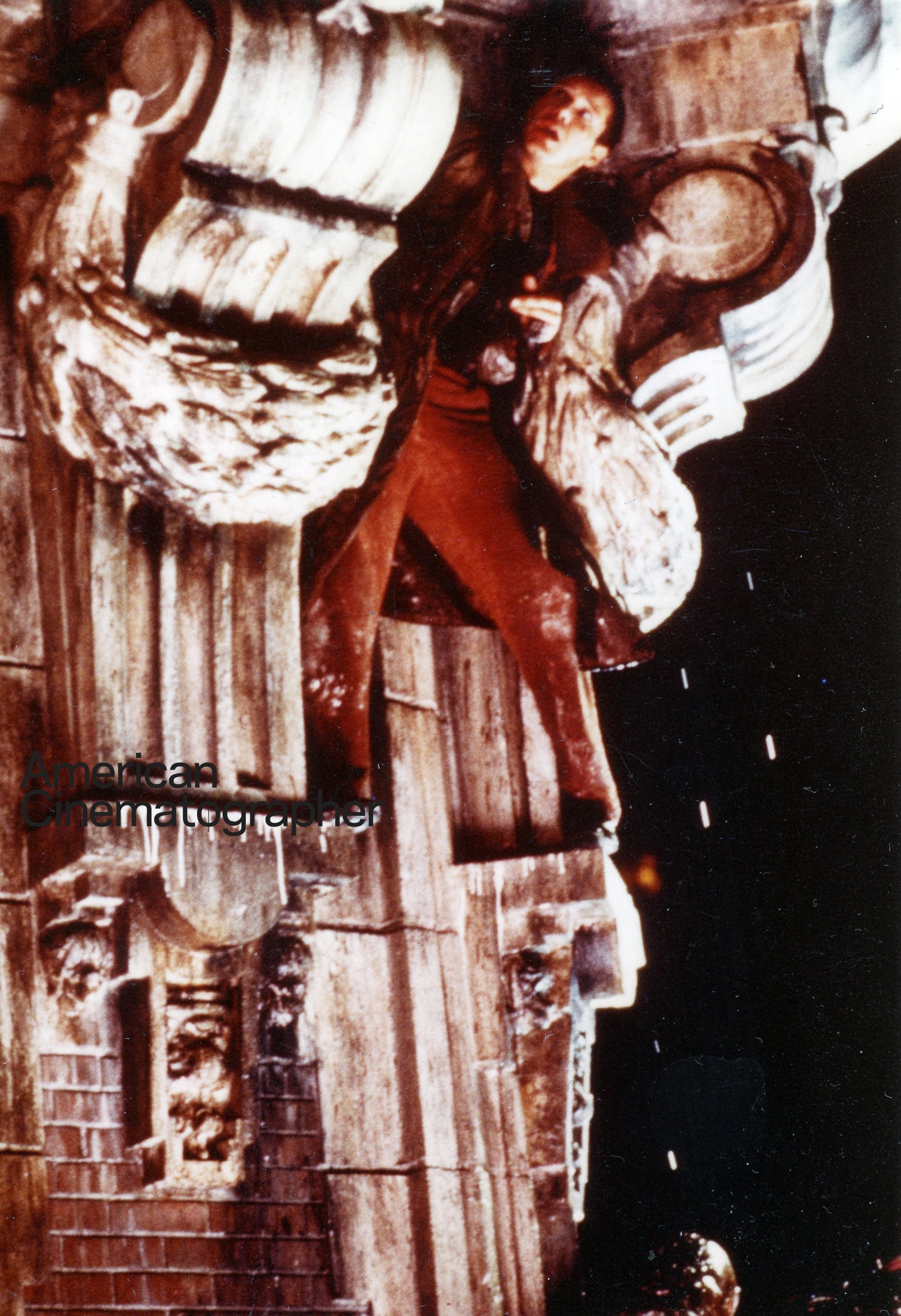

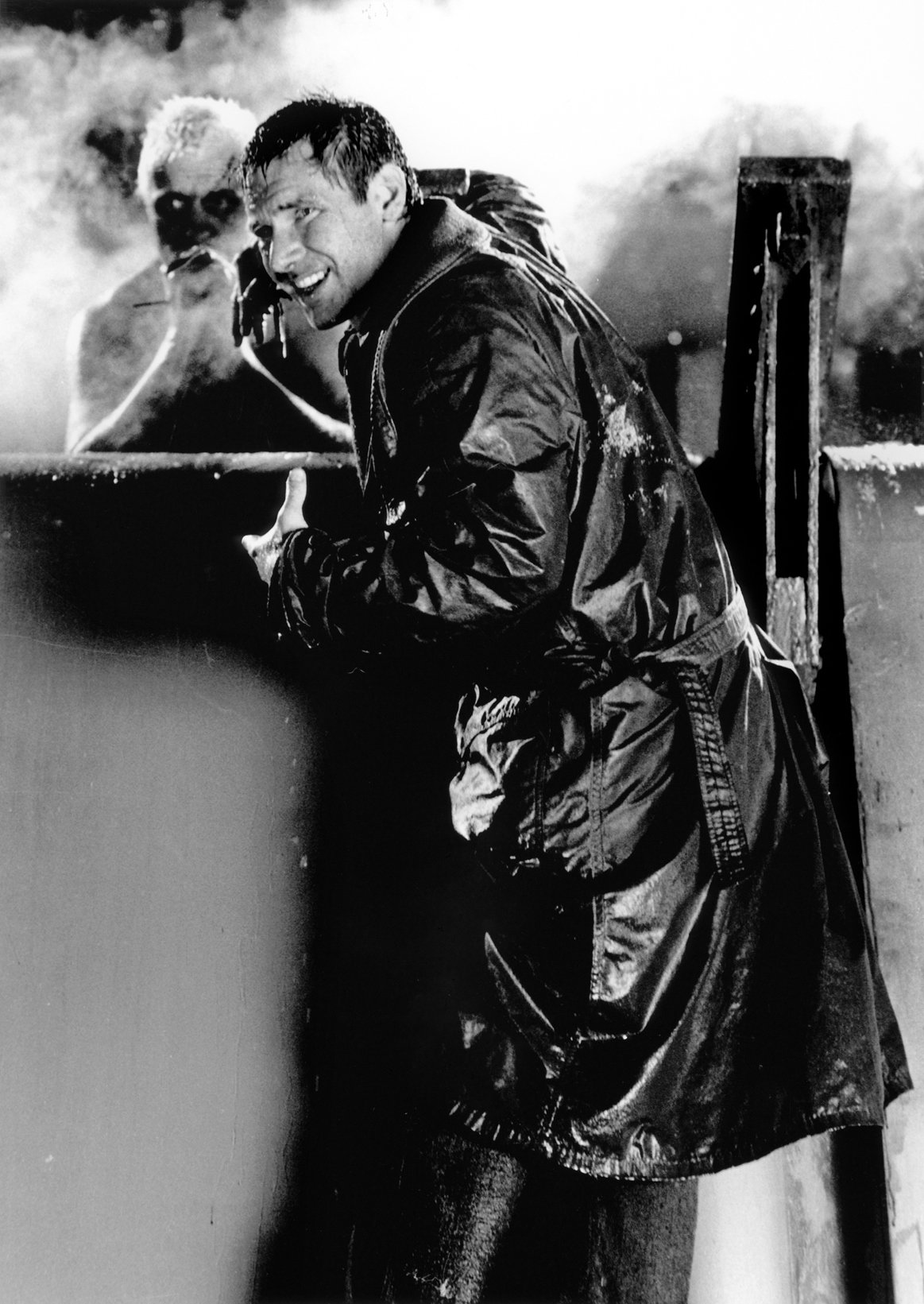

“The rooftop sequence at the end of the picture was originally planned to be photographed on real rooftops in downtown Los Angeles,” says Cronenweth. “It turned out to be impractical to do it there, however, because of the scope of the shots and the difficulty in achieving some of the effects. We decided to film the sequence on Warner’s backlot. This required building a couple of movable rooftop units approximately 30 feet high.

“In order to show extreme height, we worked very closely with Douglas Trumbull, Dick Yuricich, and David Dryer making certain key matte shots using our rooftop sets as foreground cutting pieces with the live action contained thereon. Of course whenever we did a matte shot, we'd use the 65mm camera. We had to do a lot of 65mm photography from very high parallels, which couldn’t move at all. This meant reinforcing the normal parallels with additional steel and weight. Carey Griffith made reservoirs in the bottom of the parallels and filled them with several hundred gallons of water. That in conjunction with reinforced steel going up the sides of each parallel and the use of solid bracing made a high rigid camera platform.

“We spent over two weeks on top of the roofs, turning them from time to time to obtain new backgrounds. We also worked with rain, smoke, lightning and moving shafts of light in this sequence. None of these can be used when making matte shots because they disappear in the matte area while remaining in the live-action area. One would then be confronted with matching the matte area effects to the live action rain, smoke, etc. The procedure, therefore, when doing matte shots is to put these effects into the composite on an overall basis later.”

You’ll find an account of Cronenweth seeing the completed Blade Runner with his crew here, as related by John Toll, ASC — who joined the cinematographer’s team as a camera operator soon after the film wrapped.

You’ll find our piece on the production design of Blade Runner — with futurist and concept illustrator Syd Mead — here. And on the special photographic effects here.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.