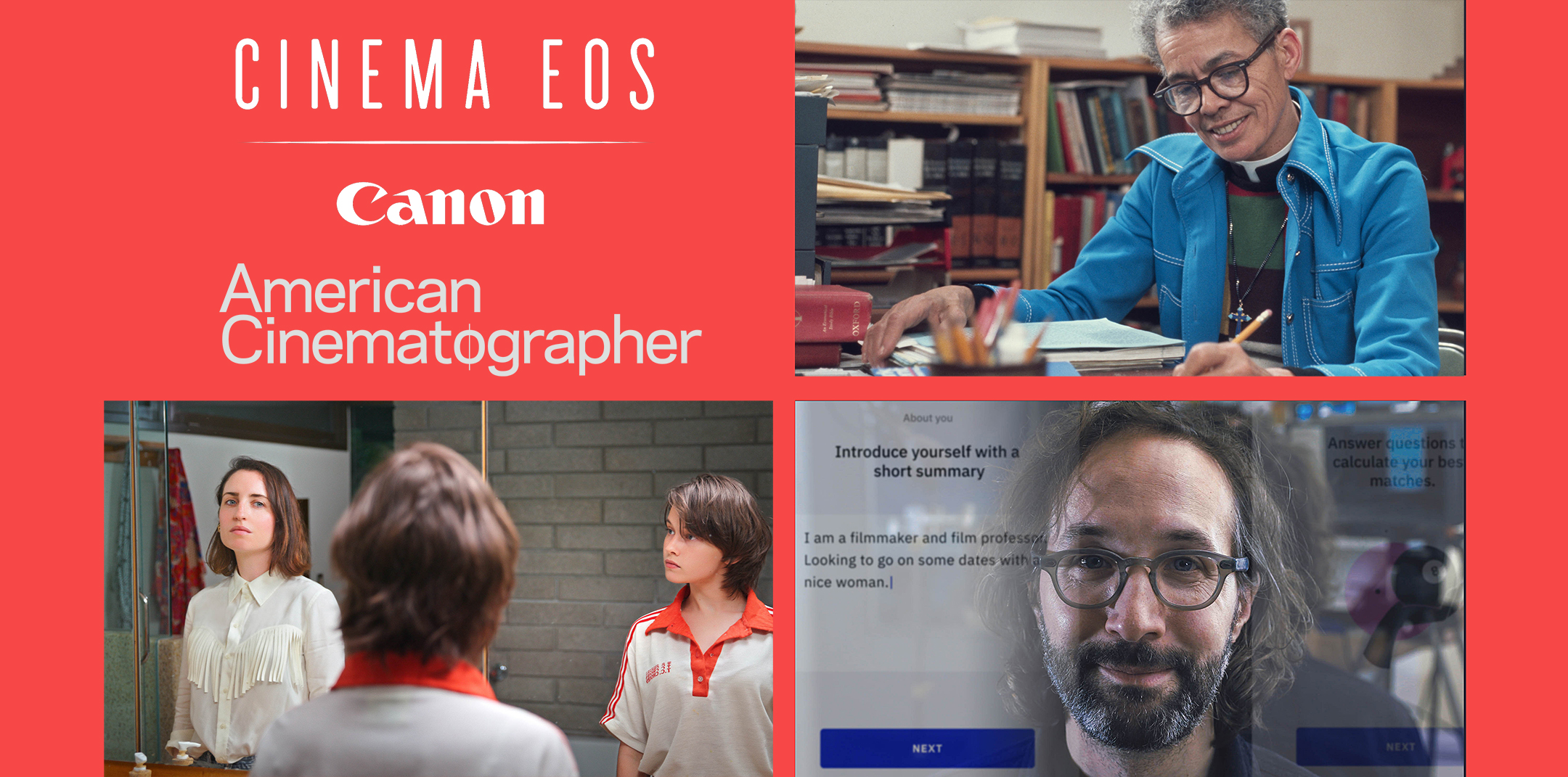

Canon Creative Studio Presents: Sundance 2021 Standouts - Part 2

Examining a selection of the festival’s most interesting features, with an eye toward outstanding camerawork.

Examining a selection of the festival’s most interesting features, with an eye toward outstanding camerawork.

By Patricia Thomson & Stephen Pizzello

Going mostly virtual for the first time, the 2021 Sundance Film Festival featured fewer movies than usual (73) but attracted an audience 2.7 times larger than its typical 11-day Utah edition, according to festival reps.

Though the excitement of unveiling new work in front of a live audience was a rare privilege — tickets for theatrical presentations were sold at just a few venues in Park City and in select cities around the United States — there was no dearth of noteworthy films. Here are a few of them, selected for their standout cinematography.

(Part 1 of this report, featuring four additional titles, can be found here.)

Censor

Cinematographer: Annika Summerson

Director: Prano Bailey-Bond

The horror feature Censor, which premiered in the Midnight category at Sundance 2021, follows the harrowing experiences of Enid (Niamh Algar), a British film censor plying her trade during the mid-1980s. Amid Margaret Thatcher’s conservative reign as prime minister of England, it was an era when “video nasties” — exemplified by blood-soaked shockers like The Evil Dead and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre — became politically charged indulgences. Censor portrays a time when Brits seeking grisly video thrills might have to negotiate surreptitious transactions with savvy counter clerks at their local rental shops to feed their compulsive appetite for onscreen deviance.

The social hysteria surrounding these types of films, which put censors like Enid in the news and on the spot, provides tense background ambience in director Prano Bailey-Bond’s picture, which begins as a low-key overview of our protagonist’s grimly mundane routine: sitting through one gruesome film after another, dutifully taking notes on scenes and sequences to drop or trim in order to make them conform to the government’s increasingly rigorous standards.

The plot turns more ominous when Enid — whose sister disappeared mysteriously during a youthful excursion the pair took in the woods — watches a film that eerily echoes her memories of that traumatic event. Obsessed with learning if the director has firsthand knowledge of her sister’s fate, Enid finds herself drawn into his B-movie orbit, where the auteur’s motivations may not be what they seem.

Cinematographer Annika Summerson makes the most of the creative opportunities inherent in the script. She imbues scenes depicting Enid’s daily existence with low-key, source-based lighting and eerie color schemes that contribute effectively to the general aura of dread. The subdued palette is enhanced with strategically placed pops of color, lending the proceedings the haunting, ethereal quality of a bad dream.

Summerson also has fun mimicking the styles of the movies-within-the-movie that Enid examines, accurately approximately the cheesy look of typical B-grade shockers. As our heroine’s investigation progresses, the look becomes increasingly more surreal as reality, fiction and memory blend together, eventually assuming the style of the video nasties themselves as events approach an appropriately over-the-top climax.

But there is more to Censor that just the lampooning of grindhouse movies. “What is it with these directors?” one of Enid’s colleagues asks after they’ve screened a particularly disgusting picture. “Male-inadequacy revenge catharsis,” Enid drily replies.

In exploring a viewer’s motivation to endure and even revel in such vicarious unpleasantries, Prano Bailey-Bond fashions a thoughtfully metaphysical excursion into the subconscious of horror fans everywhere. “Most of the time when we watch horror, it’s a safe space for us to be frightened, because we know it’s not real,” she says in an imdb.com video commentary about Censor. “In that sense, I think horror can be quite cathartic. I think of horror as the genre about the return of the repressed; it’s about the thing that you ignore in your life that is gonna come and bite you on the ass if you don’t acknowledge it.” — Stephen Pizzello

Jockey

Cinematographer: Adolpho Veloso

Director: Clint Bentley

Most films about horseracing focus on the race, not life behind the track. Jockey is an exception, which makes sense given that director Clint Bentley is the son of a professional jockey. He knew the rhythms and habits of life “backside” from a childhood spent trailing his father on the racing circuit. When he decided to make his feature debut with a film set in this world, his aim was authenticity.

Bentley found a working racetrack in Phoenix, Ariz., where production could embed. The idea was to mix actors with real jockeys and trainers and blend verité moments with scripted dialogue.

Bentley and his writing/producing partner, Greg Kwedar, penned a story about an aging jockey, Jackson (Clifton Collins Jr.), who wants to win one last championship, but whose life gets complicated when a rookie jockey arrives claiming to be his son.

Jockey was shot in 20 days, and to keep things fluid and light-footed, the crew often numbered no more than nine. There was no 1st AD; actors did their own hair and makeup; there was only one C-stand. Knowing they’d be relying on natural light, Bentley hired cinematographer Adolpho Veloso based on his work in the documentary On Yoga: The Architecture of Peace. “The shots he got in that film look like Caravaggio paintings,” Bentley said in a statement. “Knowing he could do that, we knew he could do anything.”

Veloso opted for an Arri Alexa Mini paired with Zeiss Super Speeds, a package that was both lightweight and well suited to working in low light. The cinematographer enforced a discipline of shooting two hours at dawn and two hours at dusk. Because jockeys train at the crack of dawn, that made sense story-wise, but the sunsets also suggest the waning days of horseracing.

Many of the races are seen on a monitor in the jockeys’ locker room — a clever low-budget solution, but one that could only go so far given that Jackson had to ride in two races. Those races play in tight close-up, with the actor framed from the shoulders up (something easy to cheat), racing past track rails and leaderboard. That allowed a race moment while also maintaining intimacy with the character.

The Sundance jury clearly felt the love, awarding Collins a Best Actor prize. Sony Pictures Classics felt it, too, picking up worldwide distribution rights. — Patricia Thomson

Human Factors

Cinematographer: Klemens Hufnagl

Director: Ronny Trocker

Human Factors opens with a camera prowling around an empty vacation home on the coast of Belgium, peering from room to room like a living presence. It arrives at the front door just as a family of four bursts in. A short time later, we hear a loud bang and shouting from the wife, who insists there was an intruder. This happens two more times, but each time the action is offscreen. The camera first happens to be with the husband, then the son, and finally the daughter. Was there an intruder or not? We don’t know. As the wife’s anxiety increases, doubt intrudes, ultimately fracturing what first seemed to be a picture-perfect family.

According to Brussels-based writer/director Ronny Trocker, the film is about perception and how it’s so easily manipulated. If ever there were a film wherein the camera’s point-of-view mattered, this is it.

Trocker and Austrian cinematographer Klemens Hufnagl devised a visual scheme with four different vocabularies for each family member, subtly varying focal lengths, apertures, camera heights and types of camera moves. Framing was key. Not only do we never see the supposed intruder (until the end, when the camera adapts the neutral POV of a pet turtle), but what is seen can easily be misinterpreted, like when the son spies his father “hiding” in the bushes. “Like in real life, you’re not able to see everything,” said Trocker in the Sundance Q&A.

Director and cinematographer established contrasting looks for domestic and work settings. The couple runs an advertising agency in Hamburg, and that is a cool environment, shot with Leica R lenses on a Sony PMW-F55. The vacation home is warmer, with dirtier light coming from sodium-vapor fixtures outdoors and green-tinged practicals indoors. The domestic environment was shot with softer Cooke Speed Panchros for a dreamier atmosphere. Pearlescent filters were used throughout to create cohesion in the look.

The irony of this family, Trocker noted, is that even though the parents are communications professionals, they can’t talk to their kids or even each other. “With social media,” he said, “everybody’s filming everything everywhere, and I was asking myself how this changes the way we perceive things, and how does this come into our private space? This was the starting point.” — P.T.

The Canon Creative Studio and AC also conducted a trio in-depth filmmaker interviews, which can be watched here.