Captain America: An All-American Hero

Shelly Johnson, ASC brings a super-soldier to the big screen in this Marvel Comics adaptation.

It’s the height of World War II, and the U.S. Army is recruiting soldiers in the fight against the Axis forces, even as a greater threat looms on the horizon in the form of Hydra, a shadowy organization led by Hitler’s villainous head of advanced weaponry, Johann Schmidt/Red Skull (Hugo Weaving). Steve Rogers (Chris Evans) has the makings of a good soldier — he’s loyal, honest, and brave — but he is also a 98-pound weakling who is summarily rejected by every recruitment office. Finally, he volunteers for Project Rebirth, a top-secret military program designed to create “super soldiers.” Rogers emerges as a taller, stronger, nearly perfect being: Capt. America.

Director of photography Shelly Johnson, ASC says he eagerly signed on to Captain America: The First Avenger because it offered a chance to reteam with director Joe Johnston, a favorite collaborator, and because “the story offered a lot of cinematic appeal.”

Part of that appeal, he continues, lay in the parallels between Captain America and another action-adventure film set in the same period, Raiders of the Lost Ark, for which Johnston was the visual effects art director at Industrial Light & Magic. “One of the things the two films have in common is that they take you on a long journey, and you’re rarely in the same place twice,” the cinematographer observes. “It has a cumulative effect and really helps immerse the audience in that world.”

All told, Captain America was filmed on more than 115 sets and locations. Principal photography took place in the United Kingdom, with various locations standing in for sites in the United States, Iceland, and Europe. Stage work was shot at Shepperton Studios.

The schedule was so packed that as many as seven sets were up and running at any time, according to Johnson. “This shoot was like a giant freight train: when it leaves the station, there’s a lot of momentum behind it!” he says.

“On these types of films, a large part of the cinematographer’s job is being organized. It’s the best way to manage the technical side of the job, and you can then be free to focus on the creative side of things.”

— Shelly Johnson, ASC

Seven months before the shoot commenced, Johnston and production designer Rick Heinrichs began sketching out every scene in great detail. “Preparation is the one ingredient you can’t have too much of,” says the director. “I think of prep as having two phases. In the first, anything is possible. In the second, which I call ‘the wake-up call,’ you have to compromise, to reinterpret your ideal version of the film as something you can actually put on the screen.”

While the director concentrated on building his world, Johnson concentrated on giving it light. The cinematographer starts every production by making a reference book containing camera lists, lighting lists, orders, inventories, diagrams, photos, and production art. The book is a constant presence on set, and it’s an evolving record, with Johnson updating it almost daily.

“On these types of films, a large part of the cinematographer’s job is being organized,” he notes. “It’s the best way to manage the technical side of the job, and you can then be free to focus on the creative side of things.”

Johnson and Johnston’s collaborations have been diverse — Jurassic Park III, Hidalgo (AC April ’04) and The Wolfman (AC Feb. ’10) are among them — but the director maintains that his visual style has a certain consistency. “I love letting the camera help tell the story, but I hate fatuous camera moves,” Johnston says. “In terms of my visual approach, most critics would probably consider me a traditionalist, or even, God forbid, old-fashioned. The camera is more mobile in Captain America than in any film I’ve made, and the shots are designed to continuously reveal new information, to shift focus from one character to another, to change dramatic emphasis.”

Johnson maintained maximum flexibility by keeping the A camera on a 30' Technocrane (operated by Gary and Paul Hymns) as often as possible, but “we used it more as a moving platform or a dolly, not as a crane,” he notes. “Joe would watch a scene play out and ask for changes while we were rolling, and we could make adjustments on the fly, sometimes without even cutting.”

Shooting digitally was another stage in Johnston’s metamorphosis. The director became fascinated with digital cinema after seeing George Lucas’ Star Wars prequels, but Captain America marked his first opportunity to explore it. “When Joe started talking to me about Captain America, [the format] wasn’t even a question,” says Johnson. “He asked me to shoot it, and I don’t think he even took a breath before adding, ‘And we’re shooting digital.’”

“I find the flexibility of digital technology really liberating,” says the director. “The time the camera is rolling is less precious, so I don’t have to cut in order to discuss changes with the actors. But the real advantage is in post, where I can recompose or enlarge shots without degrading the image. Sometimes we’ll reframe a shot to look like it’s from another camera. We can even make close-ups out of two-shots or three shots if we have to.”

The filmmakers chose Panavision’s Genesis for their A and B cameras. Johnson felt comfortable working with the Genesis after operating it on the ASC/PGA Camera Assessment Series (AC, June and Sept. ’09). On that project, he used the Genesis with a waveform monitor and without a digital-imaging technician, recording to Panavision’s SSR-1 digital recorder.

He used the same approach on Captain America. “We wanted to keep things simple, so we worked with a single look-up table on set,” says Johnson. Using the custom viewing LUT in the Genesis Display Processor, he slightly desaturated the image and added a contrasty film look by zeroing out the blacks and lifting the highlights to just below clip. Exposure metering was performed on a waveform monitor, and at the end of each day, the uncorrected DPX files were delivered to Deluxe Laboratories in London, where colorist Russell Coppleman graded the dailies according to Johnson's notes.

“Working off one LUT helped us out a lot because I could clearly see how the camera was performing,” says the cinematographer. “But all you really have to do to make it work is protect the values you want to print, and a lot of my exposures came from lighting the values below the highlights.”

A Schneider Optics Black Magic filter was used to give slightly clipped values a more organic feel, and a Filter Gallery Blue Streak Filter masked hot practicals with long, anamorphic-like dares.

Despite Captain America's period setting, Johnson didn’t hesitate to use an arsenal of modern lighting fixtures, tapping VariLites, Martin Mac computerized lights, space lights, wireless dimmer controls and LEDs. “They all had to be used judiciously so as not to tip our hand, but at the same time, we wanted this movie to have a modern edge,” he explains.

A variety of LED lights, including RGB-mixable and the new MoleLED (which Johnson tested for Mole-Richardson), were employed. Initially, Johnson thought they would enable him to quickly dial in colors by eye, but the first time he checked the calibrated HD monitor after lighting a shot by eye, he noticed a discrepancy between his eye and the camera’s sensor. “We were in a circular corridor in Hydra headquarters, and I had set the overhead color-mixable ribbon LEDs balanced to a very pale blue,” he recalls. “But on the monitor they appeared deep purple.” When he adjusted the color mixture while viewing the monitor to achieve the cool blue he desired, the fixtures on set actually looked green.

“The camera was either adding red to our desired color or not seeing a lot of this green,” he surmises. “The color-temperature meters we use are made to read fluorescents, gas arcs, and tungsten lamps, and all those lights occupy very specific areas of the visible color spectrum. LED light occupies enormous areas of the color spectrum, including some not visible to the eye but visible on film.”

Despite requiring some extra time at the monitor, the LEDs worked out so well that the filmmakers used them to achieve the effect of the Cosmic Cube, a mystical energy source sought after by Red Skull. The cube was designed as an intense, blue light source, small and self-contained so that Weaving could walk around with it without being tethered or constrained. Johnson and his gaffer, John “Biggies” Higgins, decided on high-output blue LEDs, and Higgins’ crew built a five-sided cube with about 64 bare LEDs on each side. Inside the cube were two 4.8-volt battery packs and a wireless DMX dimmer module to control the sources.

“It was blindingly bright and just punched through the warmer tones,” says Johnson. He explains that the film’s heroes and villains are delineated in part by color: the heroes’ world is rendered in warm colors, whereas the villains’ environments feature blue and green tones.

“When the Allies gain possession of samples of the cube technology, the signature blue source has an otherworldly presence in their warm environment,” says Johnson.

Captain America's period setting keeps the action rooted in reality, allowing the story to go to impossible places and still feel real. One particularly impossible place that had to feel real is the frozen wasteland where modern-day explorers discover Rogers encased in a block office. “It was a scene that could never have been achieved in reality,” says Johnson. “There’s an intense blizzard. It’s a day exterior with a midnight sun sitting on the horizon. All the warm sky colors had to pierce the cool ice colors. It’s an image constructed of primary elements, and if any part of the execution had failed, it would have been unsuccessful.”

The team briefly considered shooting the scene on location in Iceland, but they soon determined that Shepperton’s Stage H was a more viable option. Only a handful of elements were required to create the necessary illusion: skylight, horizon light, and a sun projected onto a muslin cyclorama behind a forced perspective glacial landscape.

“We rigged 15 4K Fresnels overhead to bounce up into 12-by-20-foot UltraBounces and go through Rosco 251 Quarter White diffusion, which gave us a soft, ambient toplight,” explains Johnson. “For the sun ball, we used a Vari-Lite 3000 spot on a dolly track behind the eye, and we moved the light as we tracked with our characters so it looked like a believable sun in the distance.” Higgins adds, “We put up about a hundred 5K eye strips circling more than half the set, which was about 250 feet by 150 feet. We were at about 25 percent on the dimmer, and that gave us a nice, red glow around the setting sun. The snow and smoke really sold it.”

Another set created on Stage H comprised several elements of the Modem Marvels Pavilion, where Stark shows off his latest technologies. Only the foreground elements were built: the main floor, six exhibit platforms, monorail pylons (the CG train was added later), and the main stage. A greenscreen eye fully surrounded the set to facilitate views of the outside, all CGI added in post.

Johnson’s crew rigged hundreds of lights in the pavilion, most of them Kino Flo Image 80s that were illuminating the 360-degree greenscreen. Six of the 4K HMI bounces created for the frozen wasteland set provided cool ambient light, which was punctuated by VariLites spotlighting exhibits on the main floor. Battens of low-profile 55-watt MR-16s, “Biggies Strips,” were placed along the base of the main stage to act as footlights.

“The main stage is the jewel of this whole set, so we concentrated on surrounding it with a more refined lighting style,” says Johnson. Above the revolving platform were three spinning Vari-Lite 3000 spots and a 12' lightbox with a space light wired to 2-3-5 behind Light Grid and V2 CTB. Sixteen Par 36 spots were installed in the upper soffit that ringed the stage.

“When I’m working with a large set or complicated lighting task, I try to simplify it down to its basic elements so that every light is serving a single purpose,” says Johnson. One of his goals with this set, he continues, was to faithfully translate Heinrichs’ concept art. “The pavilion has a spectacular look, and Rick designed a lot of the exhibits,” he says. “There is also an incredibly stylized CG set that extends into the background. Our lighting doesn’t interact with that, but it carries out the same design idea.”

One of the production's largest locations was an old Royal Navy Propellant factory in Caerwent, South Wales, which was transformed into Hydra’s headquarters in Germany. Rogers steals into the facility at night to rescue his sidekick, Bucky (Sebastian Stan), who has been captured by Hydra. Rogers and Bucky escape with the aid of some Allied POWs, but not without a fight. “That was a large installation — the buildings were about 200 feet apart — and there was an enormous amount of light around it,” says Johnson. “It was a totally artificial night exterior. I mixed color temperatures — uncorrected mercury-vapor, daylight and tungsten lamps.”

He knew some of his sources would have to be in frame, so he had his crew position four scissor lifts holding two SyncroLite 4K Xenon spots gelled with V2 CTO around the location, and then asked visual-effects supervisor Chris Townsend to replace the lifts with CG guard towers.

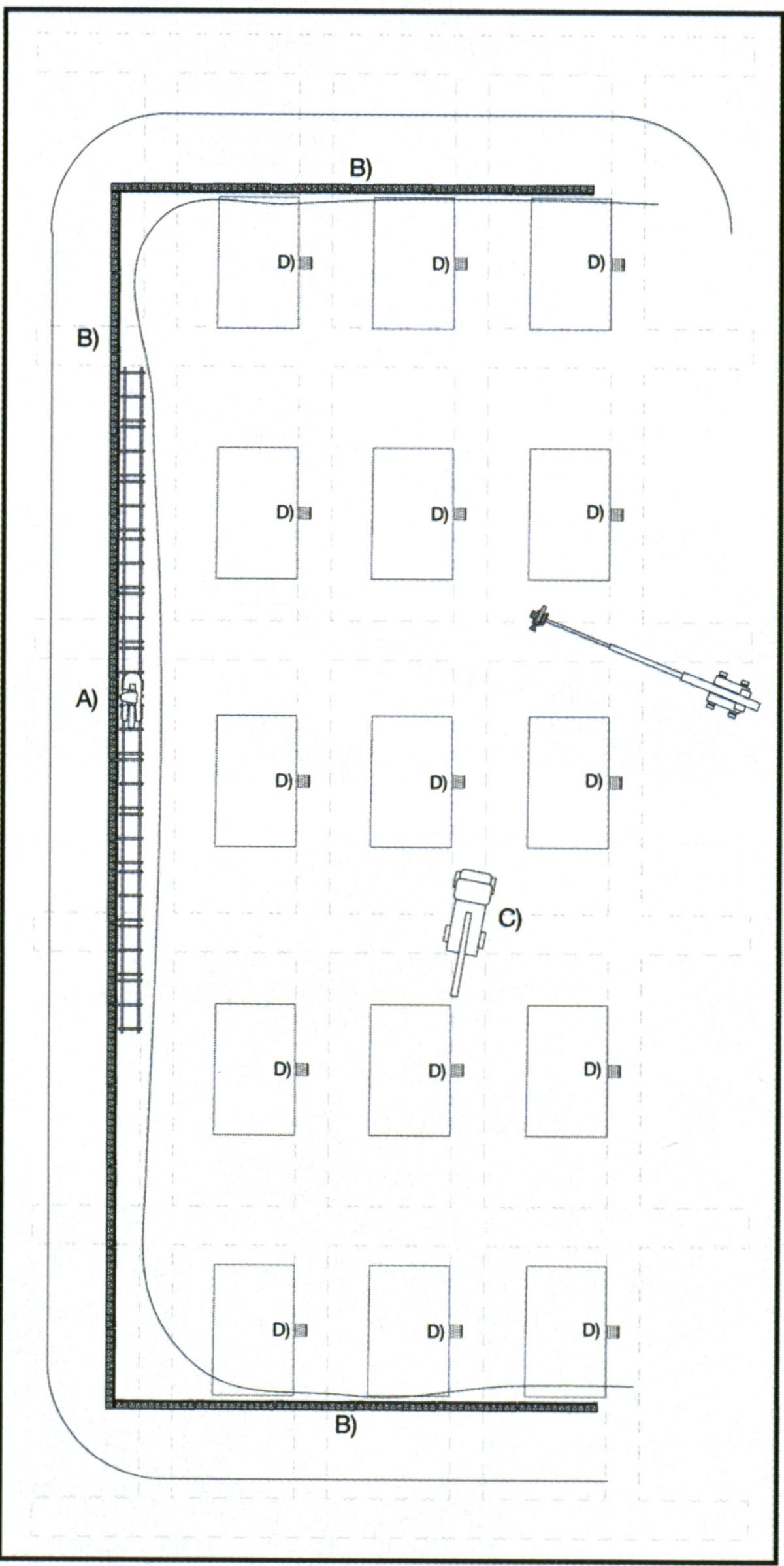

It took Higgins, rigging gaffer Wayne Leach and their crew about two weeks to pre-rig the four staging areas in Caerwent. There were so many lights spread over the area that the only way to control them all was through a DMX dimmer board. Most of the action takes place in one spot, in front of the main Hydra building, and Johnson lit the area with Vari-Lite spots and washes, Xenon lights, roving 20K and 5K lamps, and three crane-mounted 20x20' softboxes with solid sides. Inside the softboxes were 2-3-5 modified space lights rigged to a scaffold arm with jubilee clips and rigid metal bars, allowing the lights to be angled.

Higgins explains the “2-3-5” configuration: “U.K. space lights come with six bulbs in two circuits, so we take one bulb out. With the five left, we can turn on two or three, or all five, and that gives us three different light levels at the same color temperature.”

Once Rogers gains access to Hydra headquarters and attracts Red Skull’s attention, the ensuing battle was captured by 2nd-unit director/cinematographer Jonathan Taylor, ASC. After walking through the sequence with his gaffer, Steve Costello, Taylor designed the shots. He and his crew then spent five nights following stuntmen and extras with dollies, Technocranes, Ultimate Arms and Steadicams, dodging explosions as the base went up in flames.

“The problem with photographing pyrotechnics with digital cameras is that you get clipping in the fires and explosions,” notes Taylor. “Special effects supervisor Gareth Wingrove worked with me to darken the pyro by adding more cork and dust to the explosions, and different gas mixtures were used to create a richer flame. My gaffer, Steve Costello, increased the exposure, allowing me to shoot at a deeper stop.”

“Joe’s ability to integrate human moments into an action film. Now that I’ve seen it all put together, I think it’s quite masterful.”

When cameras had to be placed very close to explosions, Taylor used Arri 435s and 235s in crash housings, shooting 4-perf Super 35mm. “We also used a film camera, a [Panaflex] Millennium XL, to shoot fire and explosion plates that were beyond the dynamic-range capture capability of the Genesis,” says Johnson. He adds that underwater cinematographer Pete Romano, ASC used an Arri Alexa for his portion of the action.

Another memorable second-unit sequence shows Capt. America chasing a Nazi spy through the streets of Brooklyn. (Manchester doubled for the location.) Film and digital were mixed, with Taylor favoring the 435s and 235s for the car-mounted 15' Technocrane and the quad-bike-mounted wireless Libra head ridden by stunt rider Jean-Pierre Goy. The Libra head was mounted to a Rise and Fall rig (designed by key grip Kenny Atherfold and Camera Revolution’s Ian Speed) that could take the camera from ground level to a high angle. “Jean-Pierre is so good with the camera on the motorcycle that he’s actually like an operator,” Taylor remarks. “My operators, Tim Wooster and Peter Field, had to make a few adjustments, but Jean-Pierre always put the camera in the right position.”

The chase covers about nine blocks, but Taylor only had access to three blocks of downtown Manchester. To complicate matters, streets could only be blocked off at certain times of day, and there were rain delays. Fortunately, Manchester’s soft, overcast daylight made it easy to match shots captured on different days, and Taylor made the most of the location by shooting the available streets from every angle and redressing storefronts.

Taylor used a Canon EOS 5D Mark II to capture the moment of impact when the Nazi spy’s taxi is hit by a truck that sends it flying into the air. He hid two 5Ds with kit lenses in small Pelican cases that each had a hole cut into one side. The holes were sealed with clear Lexan polycarbonate, and the cases were painted to match the detailing on the front bumper of the truck and the back bumper of the taxi. Another 5D was rigged inside the taxi to get the driver’s POV. As the moment of impact approached, Taylor also had two Genesis cameras tracking alongside the taxi on a winch-drive remote rail system (built by Jason Leinster). “Second units really shine when they’re given authorship over a large piece of a sequence,” Johnson observes, “and Jonathan’s work is just dazzling. He understands what action is and how to make it exciting for the camera.”

Although Johnson desaturated the dailies on Captain America, he says that once he started the final color correction with colorist/ASC associate member Steven J. Scott at EFilm, “I found myself doing almost no desaturation. On the big screen, with our color choices being so simplified, desaturating the image takes the life out of it.”

Johnston trusted Johnson’s judgment completely. “Shelly is an artist with paint and brushes as well as lights and lenses,” he says. “I don’t hesitate to hand over to him all technical and creative responsibilities for capturing the image, and I know he’ll deliver something above and beyond what I had in mind.”

One of the most gratifying aspects of Captain America, the cinematographer notes, was “Joe’s ability to integrate human moments into an action film. Now that I’ve seen it all put together, I think it’s quite masterful.”

AC Archive subscribers can access this entire issue, as well as more than 1,200 others. Subscribe here.

Johnson is now 10 years removed from the release of Captain America: The First Avenger, but hasn't slowed down. In 2020 alone he added an eclectic trio of films to his resume with Honest Theif, Bill & Ted Face the Music and Greyhound.