Casino Royale: High Stakes For 007

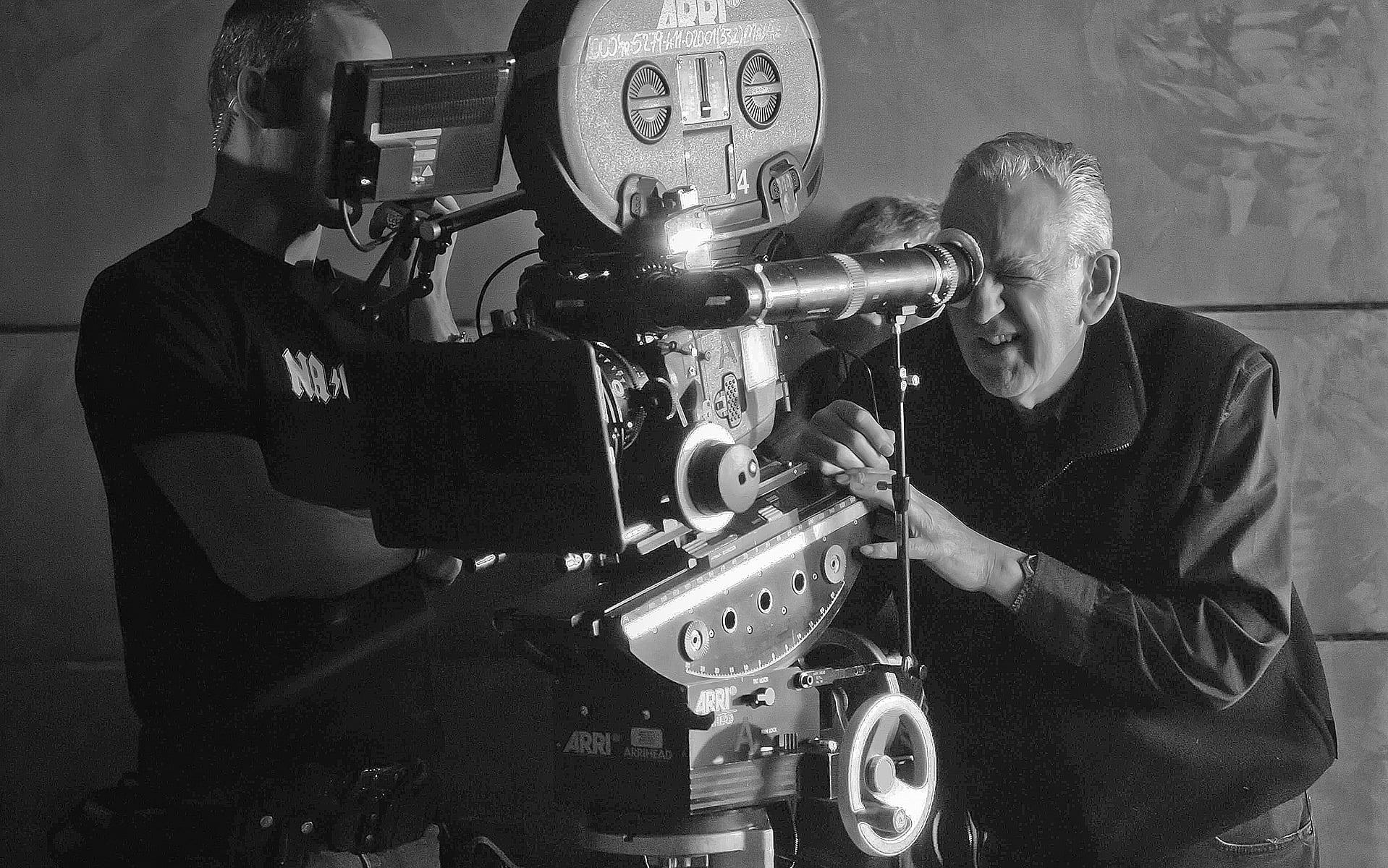

Director Martin Campbell and cinematographer Phil Méheux, BSC refashion the James Bond franchise for a new generation of viewers.

Unit photography by Jay Maidment

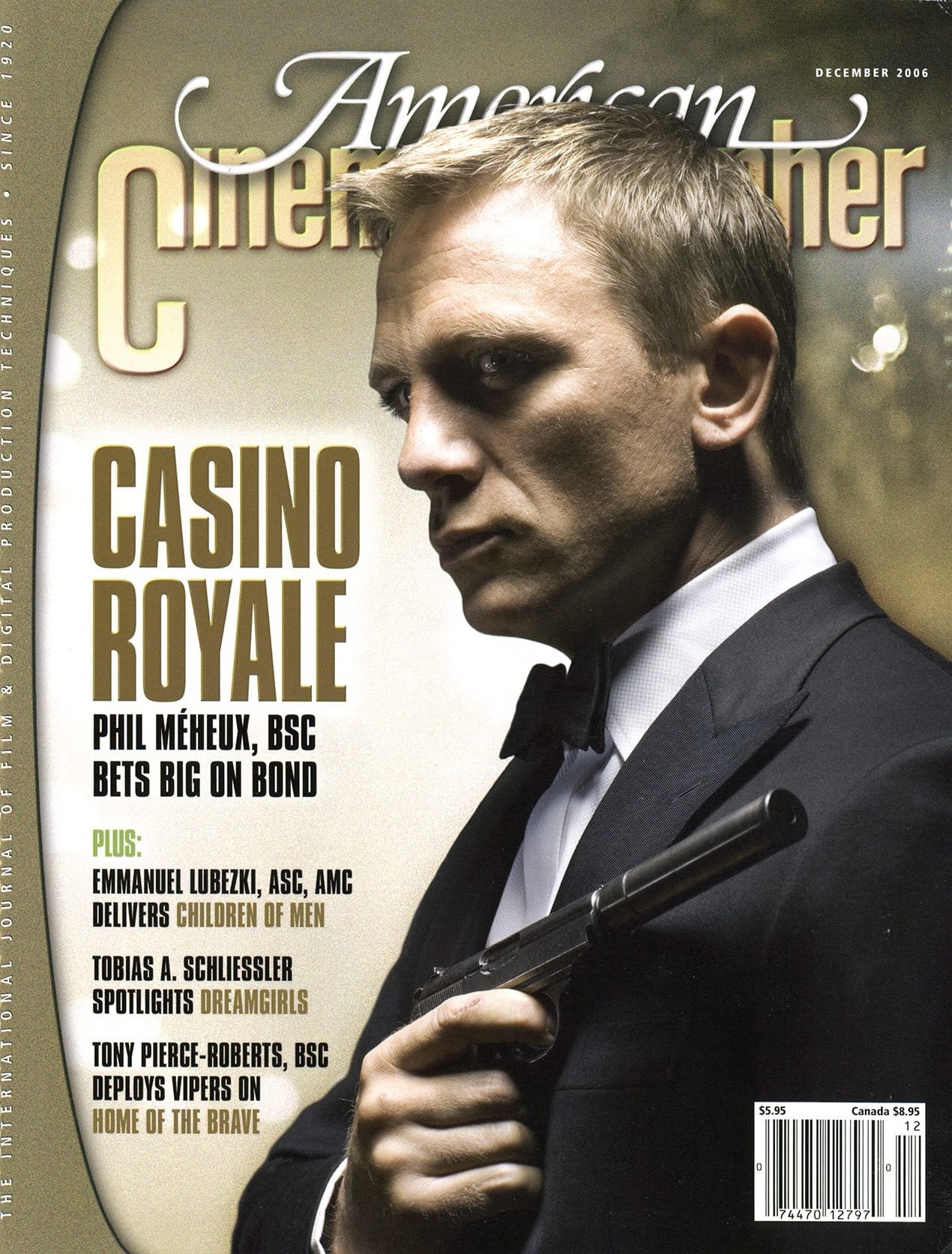

It was a different world in 1953 when Ian Fleming introduced James Bond in the short novel Casino Royale, and the secret agent who graced those pages was quite different from the suave, assured sophisticate portrayed onscreen by Sean Connery, George Lazenby, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton and Pierce Brosnan. The owners of the film franchise decided the new Casino Royale, directed by Martin Campbell and shot by Phil Méheux, BSC, should not only introduce a new lead actor (Daniel Craig) but also reintroduce Bond to the world. The picture was therefore designed with the first Bond novel, rather than any of the preceding Bond movies, in mind.

“Casino Royale is the book where Bond becomes a double-0,” notes Campbell, referring to the agent’s elite status. The Bond of Fleming’s book is in his early 30s and, especially in the opening chapters, coarse and impulsive. “He was prone to making rash judgments and thinking more with his heart than his head,” says Campbell. “He drank too much, smoked 70 cigarettes a day, and was very misogynistic. In the course of the story, he has a serious romance, and by the end he becomes the Bond we all know and love. His evolution is really what the book’s about, and that’s what this movie is about, too.”

Méheux, who has collaborated with Campbell on eight features, including GoldenEye (AC Dec. ’95), observes that Fleming wrote Casino Royale “as a straightforward thriller. The book has some very ugly scenes in it. The producers [Barbara Broccoli and Michael Wilson] and Martin all felt some of the more recent Bond films had gotten slightly off track and too wound up in visual effects. The man is a government-hired assassin, but the series was becoming unreal.”

Casino Royale has no Q Branch and no super gadgets, and the villain, Le Chiffre (Mads Mikkelsen), is not as bizarre as many of Bond’s other nemeses. Also, there are no superhuman stunts, because the filmmakers wanted the action scenes to look like they obey the laws of physics. This is not to say that the movie is totally unrecognizable as a Bond film. “The whole thing is still very up-market, of course,” says Campbell. “We’ve given it a very glossy look, as all the Bond films have. But none of the action is impossible or spacey. We never take things to a ludicrous extent.

“Phil’s a great cameraman,” the director says of Méheux. “He and I work very well together, and he’s very good at handling movies like this. You have to be tremendously organized and able to work under extreme pressure for a long time on movies like this. It can be tough and grueling. Phil always knows what I want and photographs it beautifully.”

The filmmakers decided to confound Bond fans’ expectations from the very start by opening with a black-and-white sequence, which shows Bond committing his first two government-sanctioned murders. “If you want to do something quite different and turn everyone around, do something in black-and-white!” says Méheux. “People are so used to seeing all these stunts and everything in color, and we go right into a scene of black-and-white with very little stunt work.”

The sequence was designed to feel more like spy films from the Cold War era, such as The Ipcress File and The Spy Who Came In from the Cold, than a big action film of 2006. Shot in part at Barandov Studios in Prague and in a nearby Cold War-era steel factory, the scenes deal more with character and psychology than action.

Méheux welcomed the chance to recall some of his early training in black-and-white at the BBC, and he shot the scenes on a monochrome negative. “Some people shoot color and get rid of it in the digital intermediate [DI], but I didn’t like the look of that. I also tried force-processing some color stocks, but I think if you really want the look of black-and-white, you have to shoot black-and-white film. I used Eastman Double-X [5222]. They don’t make it in large quantities, but we only shot about 6,000 feet.

“I love the way there aren’t many mid-tones,” he says of the stock. “The shadow area drops off quickly, so if you have something that’s jet black, you have to lose it entirely or put a hell of a lot of light on it. In color, the stocks seem to resolve forever and ever. You get to the DI and say, ‘Can I see what’s in that dark corner?’ and [the colorist] cranks the whole thing up and it’s like sunlight in there. In black-and-white, there’s nothing there. It’s a discipline.”

Méheux approached the two murders depicted in the opening sequence differently. For one, he used a lot of hard sources, and for the other (set in a bathroom), he transformed the entire ceiling into one big softbox and let the white walls reflect the light.

In his efforts to pay homage to classic spy films, some of which were shot in the 2-perf Techniscope process, Méheux took advantage of the Super 35mm 2.35:1 format. The greater depth of field facilitated by spherical lenses recalled one of Techniscope’s characteristics. “With Techniscope, the increased depth of field meant they were able to put things like lampshades and telephone boxes in the foreground, and they didn’t appear amoebic — you could actually see detail in them,” notes Méheux. “In The Ipcress File, there’s a shot where a table lamp is huge in the frame and a man’s face is in the top right-hand corner. I really like that look. Part of the dialogue in our opening sequence was done with very carefully controlled shots that have huge things in the foreground and faces pushed to the corners of the frame. Little things like that echo the Cold War period of spy films.”

The filmmakers’ decision to use Super 35 was prompted by the fact that a DI was a given. “There’s a certain elegance to anamorphic,” Méheux says of the format used to shoot most Bond films, “but some of that depends on the way directors work. Today, and I think this is because of television’s influence, directors seem to want the camera in closer than ever. I know Panavision has developed close-focus Primo anamorphic lenses, but you’re still using longer lenses, so the lack of depth of field can be an issue. I’ve done five films with Martin using anamorphic lenses, but he likes to work in a very kinetic way camera-wise, and I’m more comfortable doing that with Super 35.”

The production, which had six camera units in all, carried Arricam Studio bodies and an Arricam Lite (for handheld and Steadicam work), as well as Arri 435s and 235s. Méheux chose sets of Cooke S4 primes and Angenieux Imagon zooms. For the color material, he used two Kodak Vision negatives, 500T 5279 and 200T 5274, and often overexposed them slightly to add density. “I don’t like to use a lot of stocks because it confuses me and everyone else,” he declares. “I usually confine myself to two stocks, one for indoors and one for outdoors.”

Kodak’s newer 500-speed stock, Vision2 5218, was available, but Méheux says he preferred 5279 because he had been somewhat disappointed with the final colors rendered by 5218 in The Legend of Zorro. “It could have been the digital process,” he speculates. “I really don’t know. But I knew I wanted Casino Royale to be really punchy. I wanted deep blacks that still held some detail. I’m very comfortable with 5279; I’ve shot more films on it than any other.”

The camerawork in Casino Royale presents another departure, in that it involves a lot of handheld operating. “Camerawork in movies is more fluid these days,” notes A-camera operator Roger Pearce. “I’ve done more handheld work on this picture than I’ve ever done. I’ve worked on four pictures with Martin Campbell, starting with Goldeneye, and even there we did a lot less handheld work. With handheld, the action is happening in front of you. It’s almost a newsreel situation. Martin does a lot of takes and there’s always something a little different from take to take. That keeps it very interesting.”

Craig’s Bond engages in more hand-to-hand combat than the character has seen in some time. One such scene takes place inside the titular casino where much of the film’s action is set. In the scene, Bond must fight off two enemy operatives — one wielding a gun, the other a machete — in a battle that takes them down four flights of stairs. “It’s much more immediate and horrible when you get the camera right in there,” says Campbell of the handheld work. “The bad guys attack Bond and then they all go down four flights of stairs, throwing themselves over banisters and such. We built the whole set of stairs onstage at Barandov, and on each level, a doorway and window appeared to be leading to a corridor. The set went almost to the ceiling of the stage, but it was important to be able to see the whole thing and follow the fight all the way down.”

Méheux notes the importance of collaborating with the production designer — in this case Bond film veteran Peter Lamont — and the art department when creating sets. “Originally, they were going to make the stairway enclosed by four walls,” recalls the cinematographer. “I said, ‘That really that stumps me as to where the light’s going to be, because I need to look down it and up it and not see film lights.’ So I suggested we make each level look like there’s a frosted-glass window and a corridor on the other side of that. They put in these windows made of alternating yellow and white squares that gave a very interesting effect when I lit through them.”

Méheux used 5K tungsten lights without lenses and lit the glass from the other side, letting the different squares cast discernible shadows on the actors and the set. This was augmented by practical fixtures in the stairway; he was able to control these so that Bond was lit in shots featuring Craig, and in shadow or silhouette in shots featuring the actor’s stunt double.

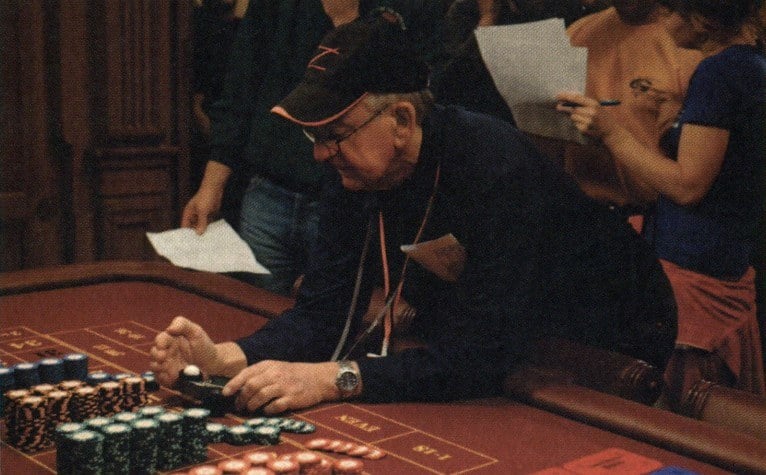

True to the spirit of Fleming’s novel, a lot of the drama takes place at the card tables, where a form of Texas Holdem Poker has replaced the more Continental game of baccarat. One of Méheux’s challenges was finding cinematic ways to cover these scenes. “There are three card games in the film,” notes Campbell. “How do you make 10 people around a table playing cards interesting? We had to discuss it quite a bit, but I must say Phil made it wonderful.”

“Betting in itself is pretty boring,” says Méheux. “The audience isn’t necessarily going to know the game, so if Bond says, ‘I’ll raise you,’ and they turn over the next card, how many people in the audience will know if it’s a good card or a bad card? So you have to deal with the drama between the characters. It’s all about looks, so you never really want to be too wide, but you also don’t want just a bunch of close-ups. We had a whole day of rehearsal with all the actors playing their cards and running dialogue, and then we worked out where best to seat everyone and how to shoot it. We tried to approach it with as many variations as we could within those limitations. We did one card game that was all filmed with a static camera, and we did another where the camera was constantly moving around the table. Then we did one game where the camera starts pretty far back and slowly closes in on Bond and Le Chiffre.”

Méheux and Campbell are very much in agreement that camera movement should be motivated by the drama. “You can fly a camera down a wire as two people are having a conversation in St. Paul’s Cathedral, and it can be fun for a moment, but you very quickly start to diffuse the drama if you’re just moving around them,” says the cinematographer. “I try always to avoid movement for movement’s sake."

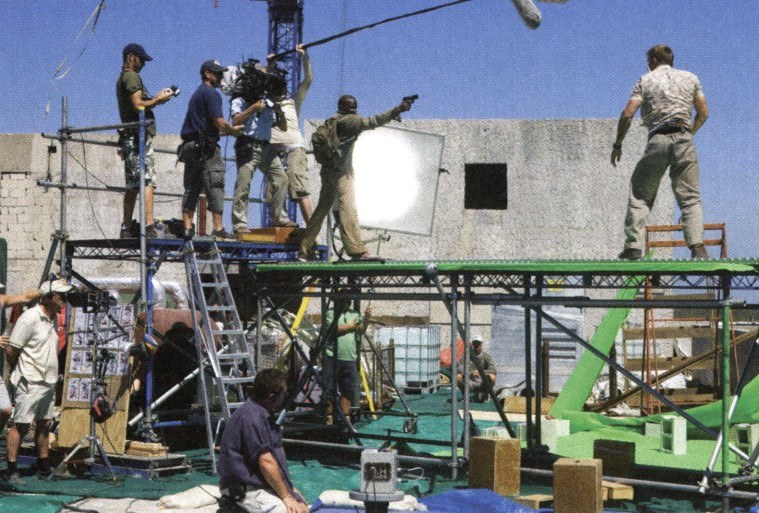

Of course, this is still a Bond film, so once the character is introduced and the new style established, Casino Royale does offer its share of big stunt and effects work. Much of this was handled by secondary units. “The tragedy of action films and any cinematographer will tell you this, is that a lot of the fun stuff is done by the second unit,” says Méheux. “We had a superb 2nd-unit director, Alexander Witt, who handled most of the big action scenes, and almost any stunt where the lead actors can’t be identified in the frame. Those shots take a lot of time; you put wire rigs up and cranes to hold people in the air, and that takes forever. You just can’t have 150 people on the main unit waiting around.”

He would discuss key information about film stocks, lenses, filtration, and printer lights with all the cinematographers, and then they would take off with their crews. (These units used Arri 435s most of the time.) “In one stunt sequence, an Aston Martin turns over on the road and flips over eight times, and apparently that set a world record for the number of turns a car has done in midair,” Méheux says excitedly.

Some of the action sequences combine stunt work, digital effects, and traditional 3-D models. One such sequence is set at Miami airport, where villains attempt to destroy a new jumbo jet and an errant 747 takes out a police car. The main unit shot the primary action at Prague’s airport and at an airfield in Surrey, England. “At the airport in Prague, all the floodlights are daylight blue with a slight tinge of green,” says Méheux. “I figured if I was going to add light to what they produced, the best thing to do was use HMIs. Then, at the field in Britain, I had the art department put up additional towers, and we bought about 30 of the same kind of floodlights they had at Prague and I used HMIs again to fill in the gaps. I warned everyone that it would come out a funny color [on film], but I knew I could pull out some of the color in the DI to make it look more like white light.”

For the view beyond the airstrip, visual-effects artists created Miami-skyline background plates. “Like a lot of big action films, it blossomed from a theoretical 80 shots to 550,” says visual effects supervisor Steven Begg. “We didn’t start out thinking of this as a visual-effects film, but it certainly became a medium-sized visual-effects film by the end.”

The effects were divided up among several London facilities, with Peerless Camera Co. doing the majority of the CGI work. Digital visual-effects supervisor John Paul Docherty explains how the Miami plates were created: “They were all keen on the look of Michael Mann’s Heat for the airport portion of the film. We shot plates of the Miami skyline with a Panavision Genesis and used it for reference in creating our CG elements. Because of differences in color space, we were worried about combining Genesis material and 35mm in the same shot.”

The effects team used Maya and SoftImage XSI to create a CG skyline, and Renderman to render the images. All compositing was done with Shake and Inferno, and these tools were also used to create, model and render the top half of the jumbo jet, which was superimposed on a 747 sitting on the Surrey airfield. By anchoring the CG part of the plane to a real one, the team had less to create from scratch, as well as a real 3-D reference to help with size and perspective issues. “I’m a big believer in the notion that it’s better to augment something real with digital effects than try to fabricate a whole scene or an entire object,” says Begg.

Casino Royale culminates in an elaborate action sequence that combined practical effects with miniatures and CGI. Bond’s love interest, Vesper (Eva Green), is imprisoned in a 17th-century Venetian villa that is being held slightly aloft from its foundation by massive helium balloons, so that damage far beneath the structure can be repaired. “For a long time, people were afraid Venice was sinking, and it turned out what was making Venice sink was the fact that houses were drawing water from wells under their foundations, and when the water went out, the foundation was sinking into the empty gap,” says Méheux. “They’ve stopped people from doing that, and Venice isn’t sinking anymore. But with that in mind, we fabricated the idea that this old-fashioned villa might be kept on the waterline with fixed industrial balloons while it was being renovated. To distract everybody, Bond shoots a balloon, and as the house starts to sink into the canal, he manages to sneak in and hide behind a pillar. Then more of these balloons explode, and the house sinks further and further with Bond, Vesper and the baddies inside.”

The interior of the house was built on the 007 Stage at Pinewood Studios. “The entire interior was a giant hydraulic rig conceived and built by [special-effects coordinator] Chris Corbould and his team, and controlled by computers,” explains Méheux. “It could twist and turn and physically drop many feet down. There were pipes underneath that could shoot water up into the set to suggest the house was sinking into the canal. It was very tricky to light, because the set was built inside a large metal casing that allowed it to be tilted in different directions. You can imagine the whole exterior of it is a complicated piece of metal trusswork that also went in front of most of the window openings. We couldn’t light from a lot of the windows anyway, because once that part of the house goes underwater, your light source is underwater too. So with Peter Lamont, we worked out the idea of lighting through skylights in the roof.

“That meant we had to bring all our light from above, pointing straight down. The set went to within 8 inches of the girders that hold the roof of the stage up, and as HMIs don’t work well pointed down, my trusted gaffer, Eddie Knight, and his team worked out a rig of Dinos with 24 Par 64s in each fixture above those girders. Under those, we hung a large silk, and then, about a foot under that, a second silk, so if you looked up, you wouldn’t see any individual sources of light. They all merged together. We added 216 diffusions to the skylights to spread the light even further. Each Dino was numbered and fed back to a dimmer panel so we could vary the light level for different angles.”

Méheux had to take into consideration that the set would drop some 20' over the course of the scene, effectively lowering the light level. “Eddie’s Dino rig solved this problem. Every time the set sank, more of the lights came into the field of view of each skylight, so even though it dropped 20 feet, the amount of light inside hardly varied. Needless to say, that was a big lighting job!”

The villa exterior was a miniature filmed in Pinewood’s outdoor tank. “The Bond movies have a tradition of large-scale miniatures,” says Begg, who also supervised the miniatures work on Batman Begins. “I thought it would be quite difficult to create the villa exterior using entirely digital effects, and I thought if we started with a miniature that looked good, we could augment it with CG and make it look totally believable.” Begg supervised the filming of plates in Venice with 120 extras looking on and practical bubble effects going on in the canal. “Then we shot a 25-foot-tall model that was designed to represent the five-story villa sinking into the tank at Pinewood. I wanted the natural light on the model to match the conditions we had when we did the Venice plates, and that gave us only about a two-hour window for shooting the model.”

Begg’s team used four Arri 435s at speeds ranging from 30-40 fps because of the scale of the water. “I was very careful not to shoot at ultra-high speeds, because I think that can be a big giveaway with water. We also shot a lot of full-scale splashes at 24 fps by dropping things like car engines into the tank. Those splashes were later composited onto the miniature.”

Deluxe Laboratories in London processed the show’s negative, and Arion Facilities transferred the footage to HDCam for dailies. Méheux supervised the picture’s digital intermediate (DI) at Framestore-CFC in London. The negative was scanned at 2K on two Northlight scanners; grading was done with a Baselight 8 system, and three Arrilaser recorders were used for output. According to colorist Adam Glasman, “The show’s color correction took six weeks, of which the first two were spent grading an HD version for previews. Once the edit was locked, we then moved on to the film DI, using the HD work as a basis. In general, the look for the film was the traditional handsome, glamorous feel [of the Bond franchise]. However, there were a couple of scenes where we went a bit over and above this. For the black-and-white sequence at the beginning, Phil had shot things to be quite dark and film-noirish. There was a danger of losing some of the details in the black clothing, so we tweaked that a bit. For the flashback fight within that sequence, Phil wanted a lot of contrast and grain applied in order to amplify the violence. We really pushed the highlights, making the scene very grainy and gritty. Then, for the Madagascar sequence, we wanted a color-rich grade that would suggest the heat and dust of a tropical island.

“I think it’s worth adding that the film has several hundred visual effects shots, which makes it the type of project that really benefits from the DI process. We were able to finesse and help bed these shots in seamlessly — the airport sequence, the sinking building in Venice, and many others. In fact, during the climactic fight sequence in the sinking house, we applied some camera shake in the DI — an effect that’s more commonly applied during the effects work. The effects people and editor Stuart Baird joined us in the digital suite to add the shake to some of the non-effects shots. It was useful to be able to review the work on the entire sequence in the DI suite, rather than on a shot-by-shot basis, and to modify and refine the effect in real-time.”

Casino Royale was Méheux’s third feature DI, and he says he loves the control the technology offers, but he still prefers to do as much as possible in-camera. “For the most part, I shoot the way I would if I were finishing traditionally. The more correct it is when I arrive at the DI house, the quicker and easier it’s going to be to grade it. Digital post tools are no replacement for getting the exposure right and making sure your lamps all match. I still want to get it right in the first place. However, DIs are perfect for films with a lot of digital effects. Nowadays, because of time constraints, many effects shots are sent to different facilities whose artists work or view on different screens. In the old days, [those shots] would be output to film till they looked right. Now they’re ingested as digital information, and there are often differences in color and contrast when it comes to the final grade because the [effects teams] were unable to see their work digitally projected with print emulation, the way we can in a DI facility. The DI process can sort these things out. I was fortunate to work with Adam, a top colorist who has studied photography. We could talk on the same wavelength, which was a great help.”

Super 35mm 2.35:1

Arricam Studio, Lite; Arri 435, 235

Cooke S4 and Angenieux lenses

Eastman Plus-X 5222; Kodak Vision 200T 5274, 500T 5279

Digital Intermediate

Printed on Kodak Vision 2383