Chopping Mall: Robots on Rampage!

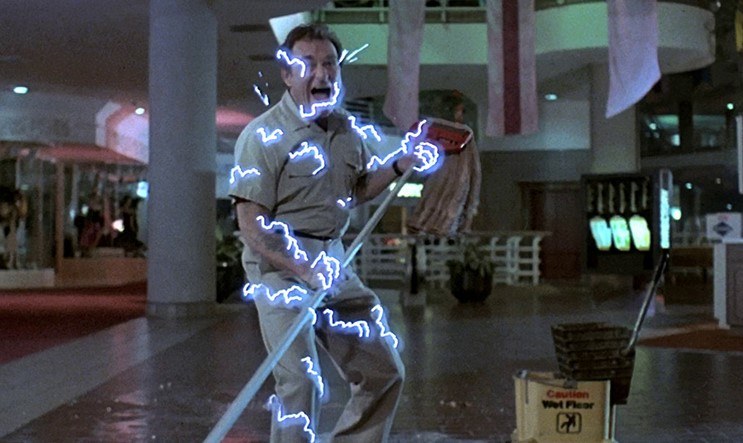

Cinematographer Tom Richmond recalls working with the Killbots, where shopping costs you an arm and a leg!

While robots are not new to cinema, they have never enjoyed the mass attention that they now receive. About a dozen films currently feature robots as central characters and some of these characters can cost as much as $250,000 each to construct.

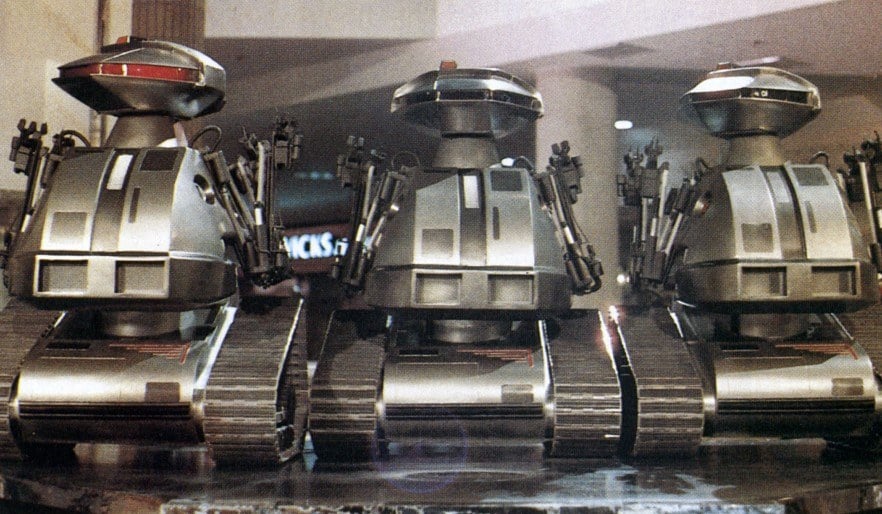

This was the problem faced by Robert Short and his crew on the new film Killbots (aka Chopping Mall) from Trinity Pictures. Short explained that, "I was having lunch when I ran into Jim Wynorski [also the director] and Steve Mitchell. They said they were writing a film about killer robots. They were looking for designers who could give them ideas from their premise, a three-and-a-half-foot-tall, fully remote-controlled robot with no possibility of a person being inside — and treads, they wanted treads like a Sherman tank.”

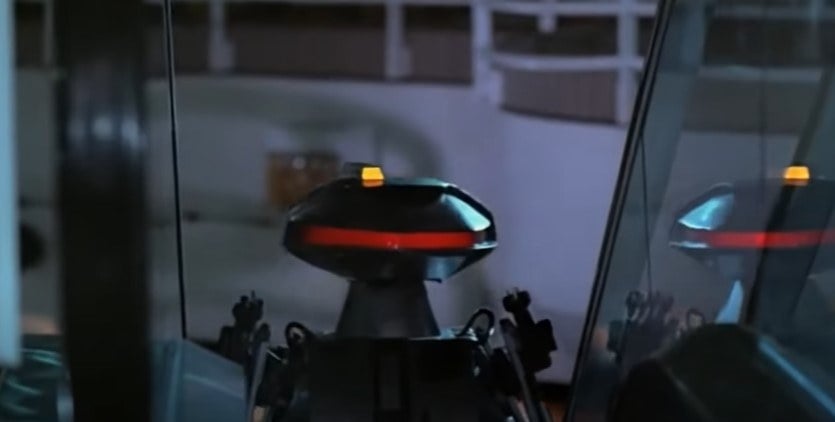

It was August of 1985 before the actual work started. This left only three months until shooting began. Short's original sketch guided Mike Novotny and his crew in the construction of several 1/4-scale foam mockups. The low, triangular base and body sections were quickly established and varied little from the sketch, but the head took some time and experimentation. Short said, "The first head design had no personality — it was simply a box. In developing a new style, 80 percent had either no character or had a whimsical feel. The more insect-like we got the more malevolent the head became. In the transition from sketch to foam, the basic evil element came into being. The asymmetrical visor captured the evil essence.”

This menacing appearance was further enhanced on the final product as described by Short: "The outside visor was smoke-grey plastic which gave a dark menacing look, and when the lights were on, the red gels created an angry, vengeful mood.

"We worked for a balance between design for design's sake and what a real-life robot might look like. For example, my sketch had the larger drive wheels in line with the smaller bogey wheels, which were on the ground. We discovered from a tank engineer that a tank's drive wheels are above ground and take no weight. They supply power and tension while the bogeys hold the weight. We incorporated this into our design."

After the approval of a miniature mockup, Douglas Turner carved a full-sized, (40" high, 35" wide) foam version which, after more revisions, guided the sculpturing of the final patterns in plaster and clay. While sculptor/plasterer Dave Schwartz sculpted the final patterns and made silicon molds, David Vivian wrestled with mechanicals and electronics to make the robots operate. Working with his brother John, Vivian utilized as many off-the-shelf items as possible; the drive mechanism was powered by two electric wheelchair motors, the drive wheels were from a conveyor belt system, and the suspension was roller skate wheels and trucks.

"The biggest godsend was the discovery of pre-made robot tread, nothing more than food conveyor belts," recalled Short. "We added applications of rubber strip to give a more menacing look." Other off-the-shelf mechanisms included lazy susans in the trunk and neck turn mechanisms and drawer slides in the front arm extension. One off-the-shelf item backfired, however. "Our buyer found a sub-miniature linear actuator which turned out to be perfect to motivate the arms. Then we found out that it was a new product; they hadn't manufactured it yet. There were only about 12 ever made and they were sent out as samples across the U.S.” By the time this was discovered, all of the R&D time had been exhausted and the arms already built to fit the actuator. After many phone calls and much pleading, the rest of the actuators were tracked down a week before delivery.

By the time the major patterns and silicon molds were finished, many of the accessories such as grappling hooks and tasers were completed. Rob White did most of the fiberglass work with the help of Turner and Luc Mayrand. Don Matheson was busy casting smaller parts in polyurethane while Cathy Quill made-up dummy arms for the shell robots.

"Many of the electric-mechanical parts never meshed with the fiberglass shell units until we did the final assembly," said Turner. "Our first real test was held in front of the producer and director on a Saturday morning after we'd worked all night to get it ready. It's the worst feeling in the world to test things in front of an audience.

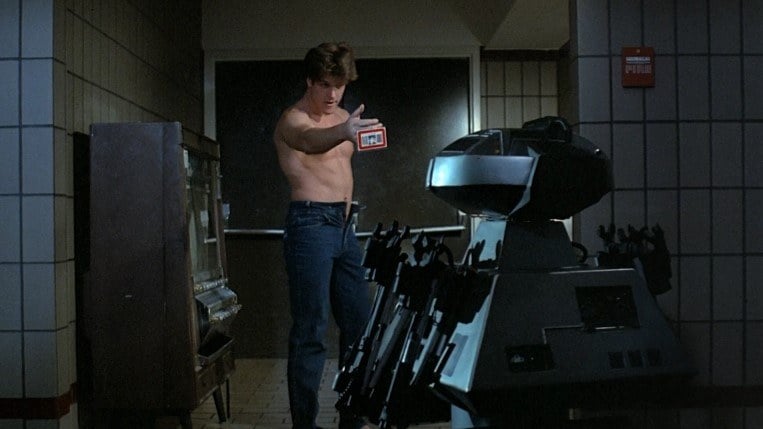

"Once the late nights at the Marina Del Rey shop were complete, the robots were transported to the Sherman Oaks [Calif.] Galleria, where most of the principal photography was to take place. We never had time to practice with the robots before moving them to the location. We literally learned how to operate them while we were shooting."

"The Galleria is the best possible location for shooting low budget," explained director of photography Tom Richmond. "I got a good feel for shopping malls when I was shooting second unit for Night of the Comet. We tried to enhance the environment and work with what was already there, instead of trying to be creative geniuses. We didn't want to make it like a haunted house; we wanted to see the place, but just barely. We took advantage of the storefronts with all their little source lights. We didn’t go for a lot of big shadows, but it had to be dark and scary enough that you didn't know if there was a robot back there.

''Once we set up the basic light, filling the place with a sort of no-color blue at a very low level, as a neutral, colorless look, and with highlights from all the stores, it became fairly easy to light a huge area. Then, depending on whether it was people or what, we'd go for a key or an edge that seemed to fit the scene. We could get a bunch of shots relatively quickly. Because of this consistency, we could get away with a weird edge or something dramatic because it was still within the bigger visual continuity.

"We were working with fairly low light levels in there. We shot most of the time on a 2.8/4 split and used a lot of wide-angle lenses which enabled us to be pretty fluid and wild in our photography. The camera moves a lot. Having flat floors and a really good, imaginative dolly grip enabled us to move the camera fast and do fairly elaborate chase shots without massive amounts of setup time. We didn't have a Steadicam or thousands of feet of track or a crane. We were able to go flying down those halls with either the kids or the robots.

In all, Short's crew built five robots, and a closeup section of a robot chest, but only two robots were fully functional. Of these, one was radio remote-controlled, and the other had the same functions, but its control box was attached to a 15-foot cable. The other three robots were "stunt'' robots that could be positioned or pulled along on cables. They were used for scenes in which the robots crash through windows or get blown up. The radio-controlled robot (nicknamed Remo) became the primary workhorse with the cable unit (Rambo) as backup. This was planned from the beginning because of the potential problem of radio interference. A 400-lb. robot out of control could cause a lot of damage to equipment, personnel, and, of course, itself. There was also a conveniently located kill switch that would disconnect the transport drives if the robot got out of hand.

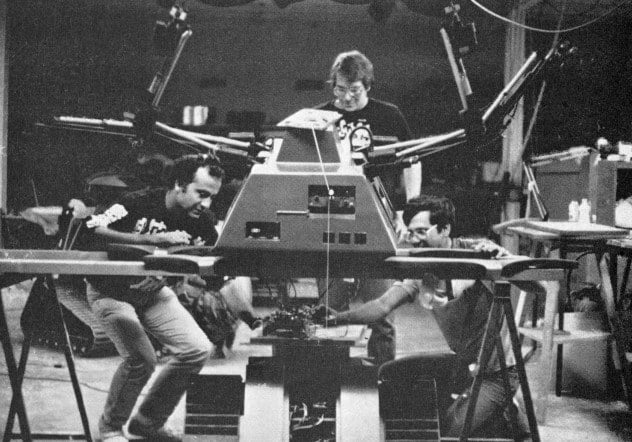

The cable robot posed its own problems. Whereas the radio operator could work from almost anywhere, the cable control box could be at most, 15 feet away. This led to problems hiding not only the cable but the robot operator as well. Turner explained, "I had to hide under a black drape beneath a bench for one shot, and for another, I had to drive the robot around a blind corner. I ran him right into the camera; luckily we had sandbags there for just that reason."

Turner and White were charged with the responsibility of operating and maintaining the robots during four weeks of shooting in which the robots worked every night. White became the primary driver of the remote control robot, while Turner operated the robot's arms or the cable robot. The director soon learned that the robots needed marks and rehearsals just as the actors do, even though they never asked about motivation.

"We were experimenting with lighting the robots all through the film," Richmond recalled. "I found that because they were sort of reflective and had such a nice shape to them that they needed almost no light to light them. I thought it was going to be a problem initially because they were dark. It went against a lot of my disciplines, if I tried to do an edge light or light the body and not the head, it didn't work. It was better to just let them reflect the windows and lit objects. They pick up the smallest lights and throw them right back at the camera. When we did light them, we used a dull blue side light to give them a cold, metallic, industrial look.

"I think it's important not to over-reveal them. It makes them scarier. They're not very big, and you can take them as toy-like if you just saw them sitting there. The idea is that the machine does not have to be big to be powerful. I was hoping to get across the coldness and pure functionalism of the things. Size was not that important because of their power. I wanted to emphasize how insidiously scary they are rather than their size."

The camera was usually low, and often showed only a part of the robot. The camera was frequently undercranked at 16 to 20 frames per second. Several shots were accomplished by mounting both the camera and robot on the Western dolly and rolling them around the mall. Certain shots were particularly effective in showing the robots as free, autonomous beings. Among these were high-angle shots of a robot maneuvering in tight areas and one in which the robot rolls into a glass elevator and spins around as the door closes behind him.

"One of the reasons I got involved in the film was because of the robots," Richmond said. "It was a chance to photograph technology. It was hard for me to give a lot of that over to the second unit."

Second unit cameraman Steve Carpenter had to match Richmond's style as closely as possible. Since both units were working in the same area, the two of them were able to consult regularly to make sure the look of the film remained consistent. This same luxury did cause problems when both units were scheduled to shoot in the same place at the same time. Second unit often had to stop work while first unit shot a sound sync scene; echoes travel far in a shopping mall. Carpenter kept being pulled away from second unit to run a second camera on stunts or effects sequences. Since the robots were sometimes working on both first and second unit, White and Turner were required to split up. Turner said, "Rob took second unit with the remote control unit, while I stayed with the first unit which worked at a much slower pace. But, having only one operator did cause problems. In one shot, on cue, the robot's lights come on, he rolls forward to a mark, raises one arm then the other, and turns his head. I had to recruit extra help for that one.”

There were a number of actions in the script that the robots simply could not perform. "We had to cheat these," explained Turner, "for delicate arm movements such as when it grabs someone's throat or picks up a fire extinguisher and throws it, we used a separate mechanical arm with a bicycle hand brake to work the claw. In another sequence, an overturned robot was supposed to push itself upright by its arms. We loosened the arms on one of the stunt robots so that they would rest on the floor, then Rob and I simply grabbed onto the treads and pulled it up. We cut to a medium shot of the robot coming to a fully upright position." The biggest "cheat," however, was the escalator sequence. When the robots were designed, the film was supposed to be shot at the Beverly Center [mall] in Los Angeles, which has very wide escalators; the Sherman Oaks Galleria doesn't. The robots were several inches too wide. To make matters worse, the sides of the escalator are transparent.

"For our final solution, we took the head and body off one of the stunt robots and wearing the robot like a costume, I sat on the escalator. I couldn't see, so Rob had to lead me on, then come in and pull me off before the escalator hit bottom. They accomplished two shots this way; one over the robot's shoulder and the other of the robot coming up over the horizon."

"Halfway through the film I started to fall in love with the robots," recalls Richmond. "They really developed their own characters and performed better and better as the shoot went on. I was impressed with the durability of the things. Working the robot 12 hours a day for 4 weeks, I was always afraid they would break down and have to be rebuilt."

The robots held up well during the weeks of shooting and were only taken apart once for maintenance. There was virtually no downtime. There was, however, one accident in which a robot ran into the bottom of the escalator. It broke its head off and smashed one of its claws. It was quite a spectacular shot because a small explosive pellet hit the head in the same instant. An attempt was made to rewrite the picture so they could use the shot, but it wasn't possible. The robot crew lost some sleep that day trying to repair the 'bot for the next night's shoot.

The most time-consuming maintenance turned out to be changing treads all the time. The original design involved a hard plastic tread with a thick rubber strip on each section. This worked very well when the aluminum chassis was tested in the shop. However, with the fiberglass body sections and the upper body mechanics placed on top, the treads got too much traction; the maneuverability was reduced. On carpet the robot would scarcely turn at all. Two of the stunt robots had been outfitted with the same tread but with tape strips instead of thick rubber. The result was not as pretty, but more functional. After a few nights' shooting, a decision was made to use the "hero" treads whenever the robot was stopped and the others when they were traveling.

"There was a certain satisfaction to watching one of them caught in the great fire at the end," Turner recalled. "It was one of the robot dummies of course, but we tied the arms in the upright position with monofilament so that they would drop when the line melted. The head fell off slightly too, which gave it a very dead look."

"My favorite shot of the fire was with a 135mm lens, close up on the robot." Richmond said. "We shot at 60 fps, with the robot engulfed in flames." "Flames in the daytime always look great — they always look like flames, but at night you're lighting normally at a 2.8 or something like that. The flames are at 5.6, 8, or 11; they're really bright. So in order for them to come out orange, you have to light at a higher level. Otherwise, the explosions just come out white."

Whether or not Killbots is remembered as a film, robot fans undoubtedly will remember its robots with fondness and picture them along with Robbie and Gort in the annals of robot history.

Author Allen D. Lowell is a scupltor and model maker in Hollywood.

Cinematographer Tom Richmond later shot such features as The Chocolate War, Stand and Deliver, Little Odessa, Killing Zoe, Slums of Beverly Hills, House of 1,000 Corpses and Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist.

Richmond joined the ASC in 2012 and passed at the age of 72 on July 29, 2022.