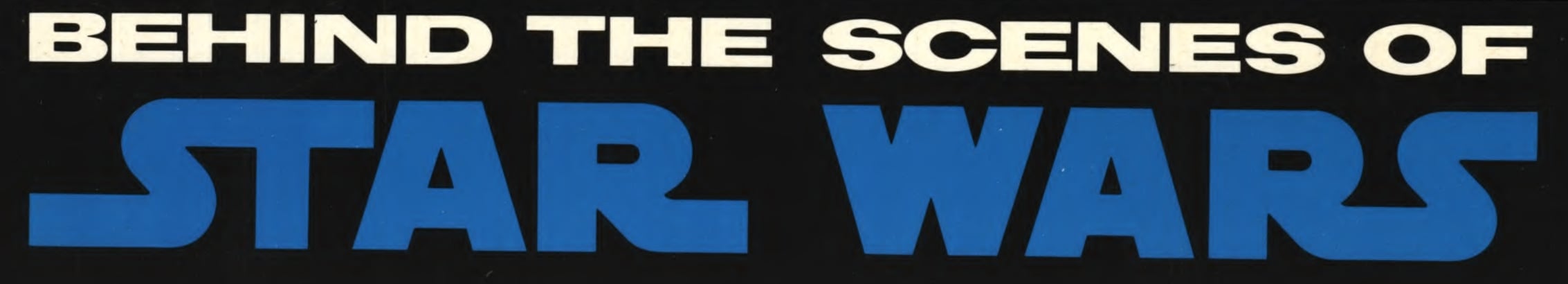

Behind the Scenes of Star Wars

A young, enthusiastic crew employs far-out technology to put a rollicking intergalactic fantasy onto the screen.

This rare look at the making of Star Wars originally ran in AC's July 1977 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

Editors' note: This story's original text has been lightly edited.

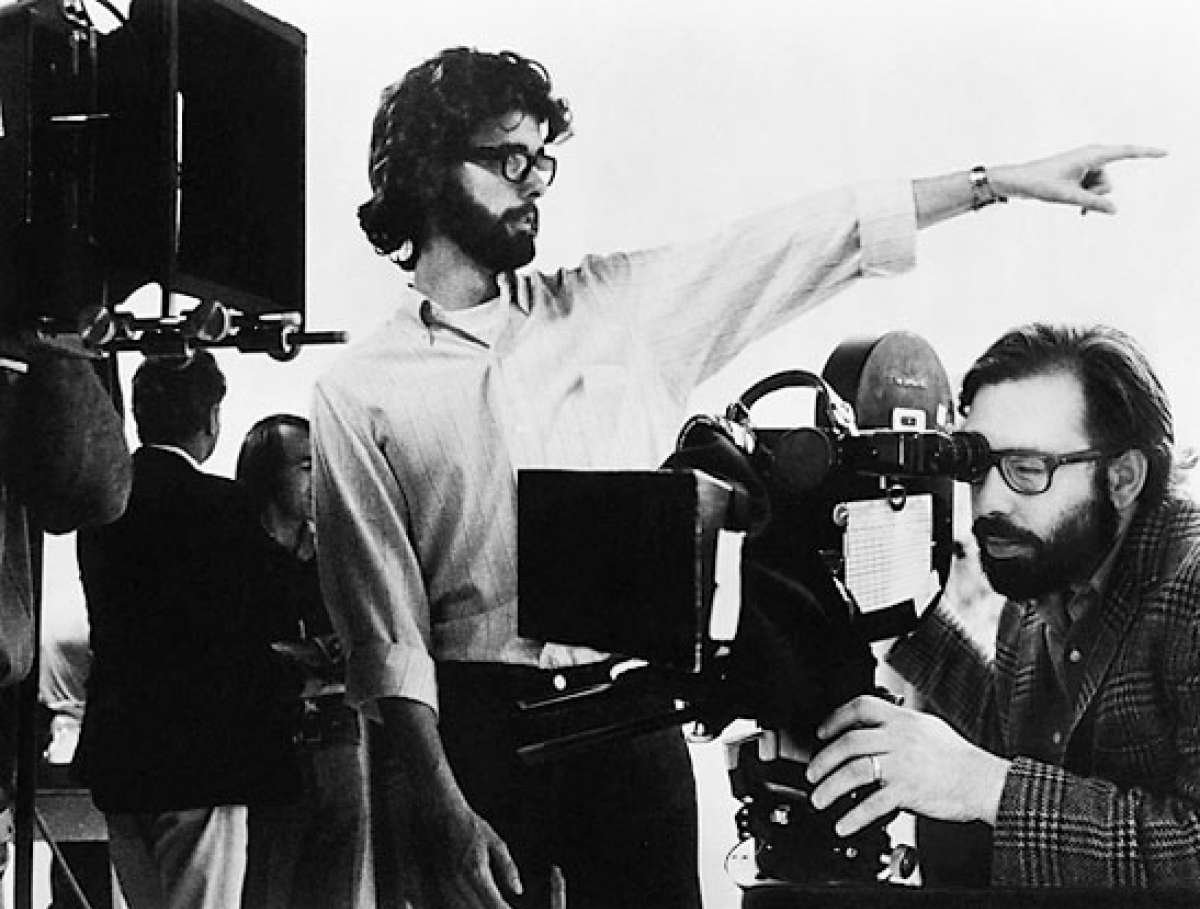

To paraphrase a statement attributed to Orson Welles during the filming of Citizen Kane, the most magnificent toy ever invented for grown men to play with and express their fantasies, to project their nightmares and dreams, and to indulge their whimsies and secret desires is the motion-picture medium. Taking full advantage of the technical wizardry of modern filmmaking, writer-director George Lucas has conceived of his film, Star Wars, as an expression of his boyhood fantasy life, his love for Flash Gordon and all the great mysteries and adventures in books and movies. Star Wars is a distillation of the joys of Lucas experienced in the hours he spent watching television and movies, and reading comic books and comic strips. It is also the most ambitious space film since Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, as well as being quite possibly the most spectacular display of intricate special effects ever to sweep across the screen.

Star Wars, produced by Gary Kurtz, stars Alec Guinness, Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher and Peter Cushing. It is being released by Twentieth Century-Fox. It's a high-energy action movie, uniting the hardware of contemporary space adventure with the romantic fantasies of sword and sorcery, plus a dash of wish fulfillment. Lucas' goal has been to make an imaginative entertainment experience that would transport audiences out of the theater and into an unknown galaxy thousands of light years from earth.

As early as 1971, Lucas had wanted to film a space fantasy. "Originally, I wanted to make a Flash Gordon movie, with all the trimmings, but I couldn't obtain the rights to the characters. So, I began researching and went right back and found were Alex Raymond (who had done the original Flash Gordon comic strips in newspapers) had got his idea from. I discovered that he'd got his inspiration from the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs (author of Tarzan) and especially from his John Carter of Mars series books. I read through that series, then found that what had sparked Burroughs off was a science-fantasy called Gulliver on Mars, written by Edwin Arnold and published in 1905. That was the first story in this genre that I have been able to trace. Jules Verne had got pretty close, I suppose, but he never had a hero battling against space creatures or having adventures on another planet. A whole new genre developed from that idea.

"I had the Star Wars project in mind even before I started shooting my last picture, American Graffiti and as soon as I finished I began writing Star Wars in January, 1973, eight hours a day, five days a week, from then until March, 1976, when we began shooting. Even then, I was busy doing various rewrites in the evenings after the day's work. In fact, I wrote four entirely different screenplays for Star Wars, searching for just the right ingredients, characters and storyline. It's always been what you might call a good idea in search of a story.

"What finally emerged through the many drafts of the script has obviously been influenced by science-fiction and action-adventure I've read and seen. And I've seen a lot of it. I'm trying to make a classic sort of genre picture, a classic space fantasy in which all the influences are working together. There are certain traditional aspects of the genre I wanted to keep and help perpetuate in Star Wars.

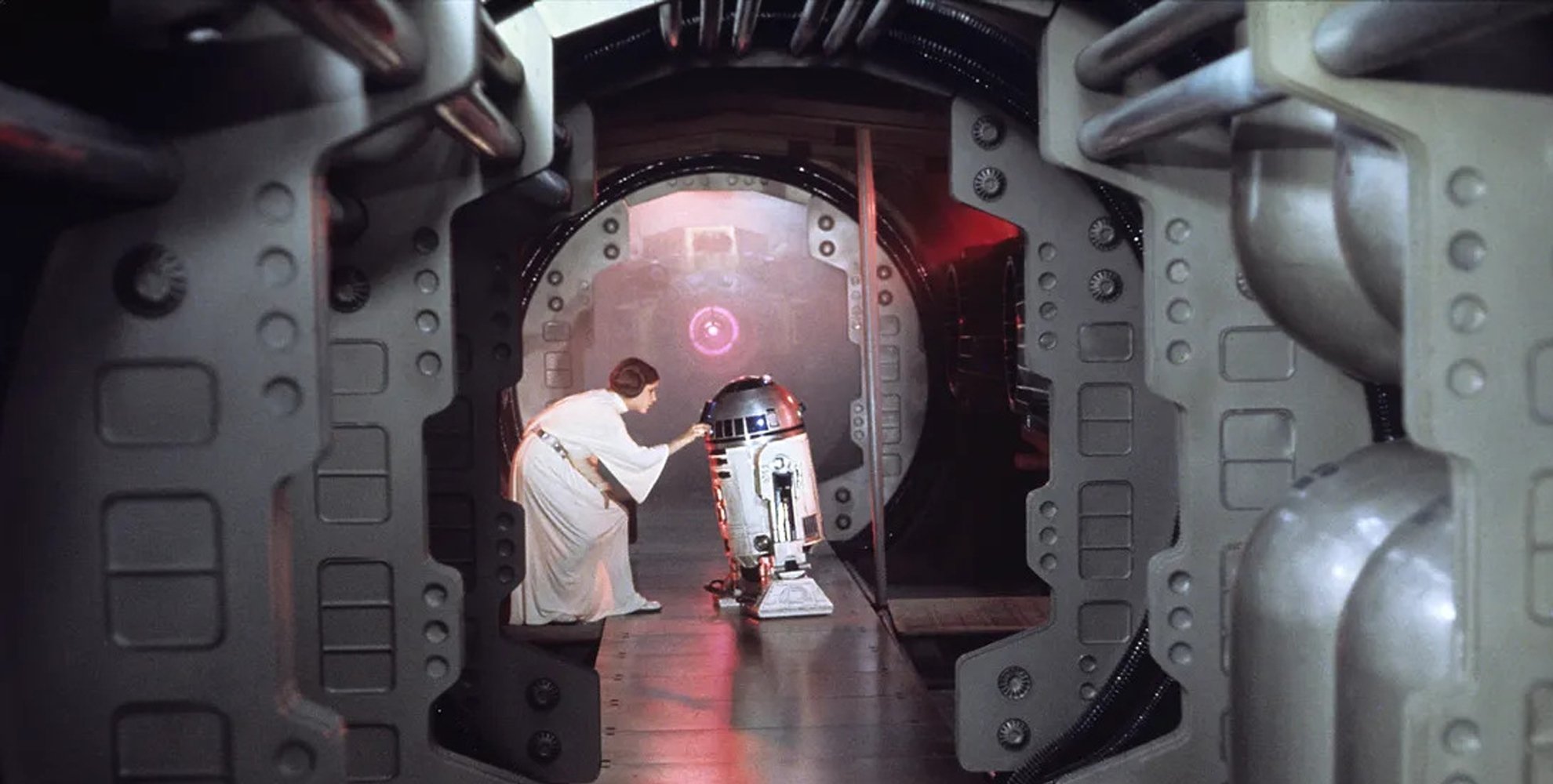

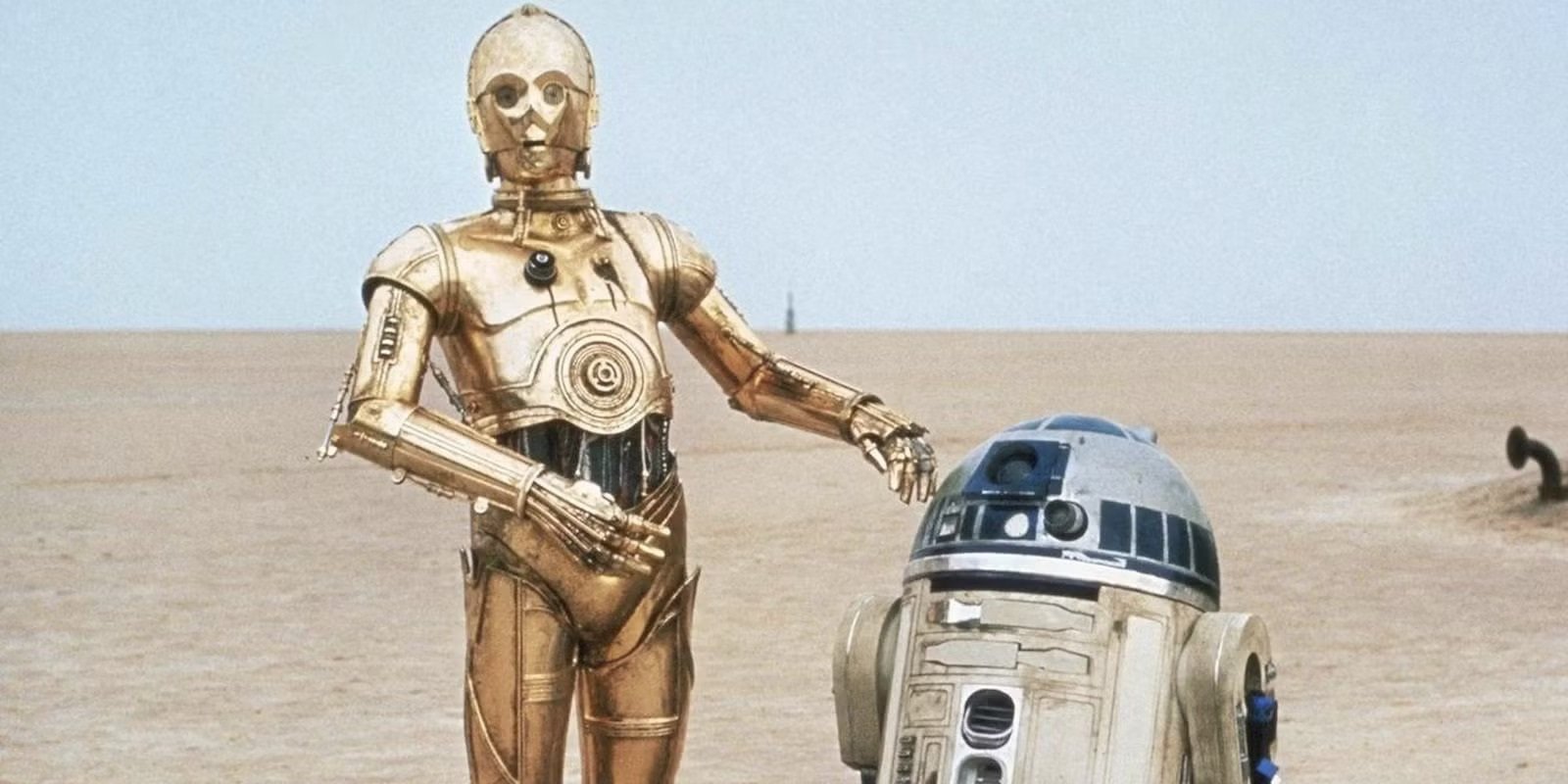

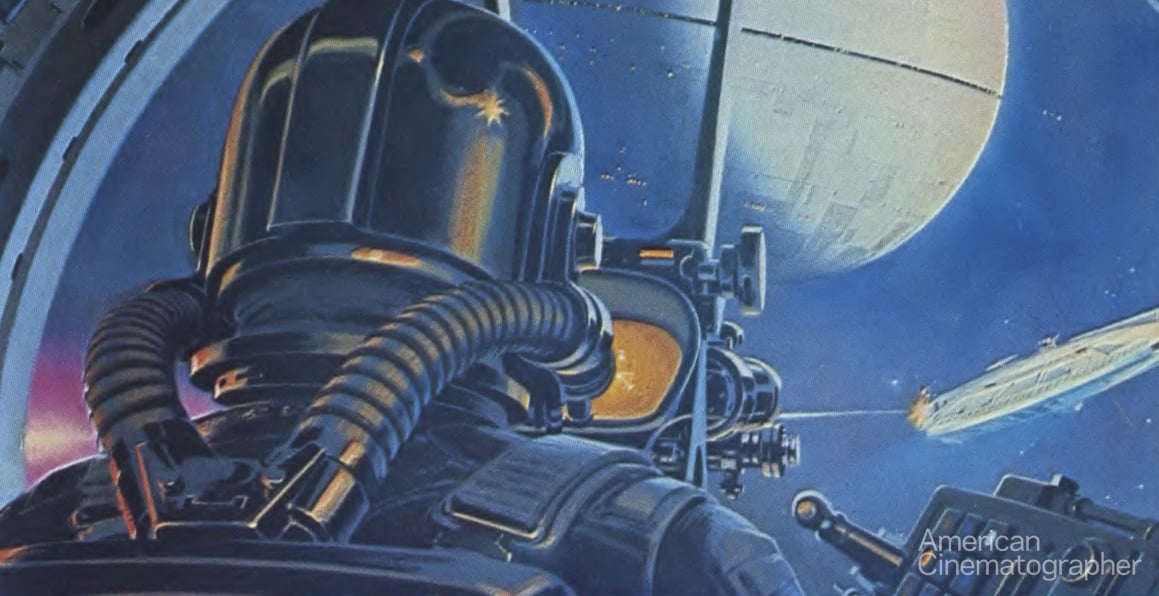

Star Wars follows a young man, Luke Skywalker, through exotic worlds uniquely different from our own. Leaving the small arid planet of Tatooine, Luke plunges into an extraordinary intergalactic search for the kidnapped Rebel Princess Leia from the planet Alderaan. Luke is joined in this adventure by Ben Kenobi, the last of the Jedi Knights who were the guardians of peace and justice in the old days before the "Dark Times" came to the galaxy; Han Solo, the dashing, cynical captain of the Millennium Falcon, a Corellian pirate ship; Chewbacca, a Wookiee, one of a species of tall, furry anthropoids; and the robots, See-Threepio (C-3PO) and Artoo-Detoo (R2-D2). This odd band of adventurers battle Grand Moff Tarkin, the evil Governor of the Imperial Outland regions, and Darth Vader, the malevolent Dark Lord of the Sith, who employs his extrasensory powers to aid Governor Tarkin in the destruction of the rebellion against the Galactic Empire. In the battle of Yavin, Luke engages in a terrifying climactic space battle over the huge man-made planet destroyer, Death Star.

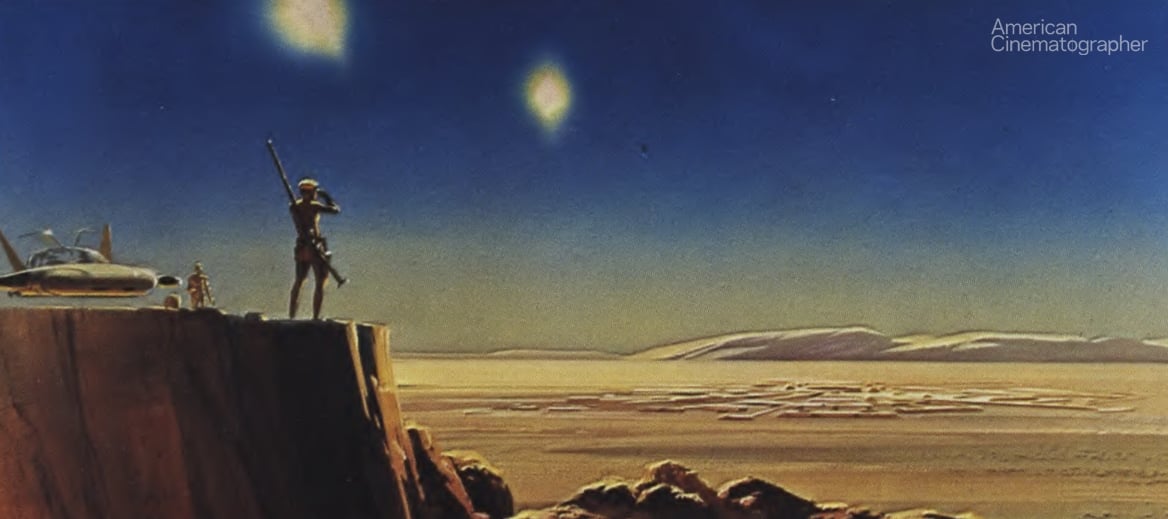

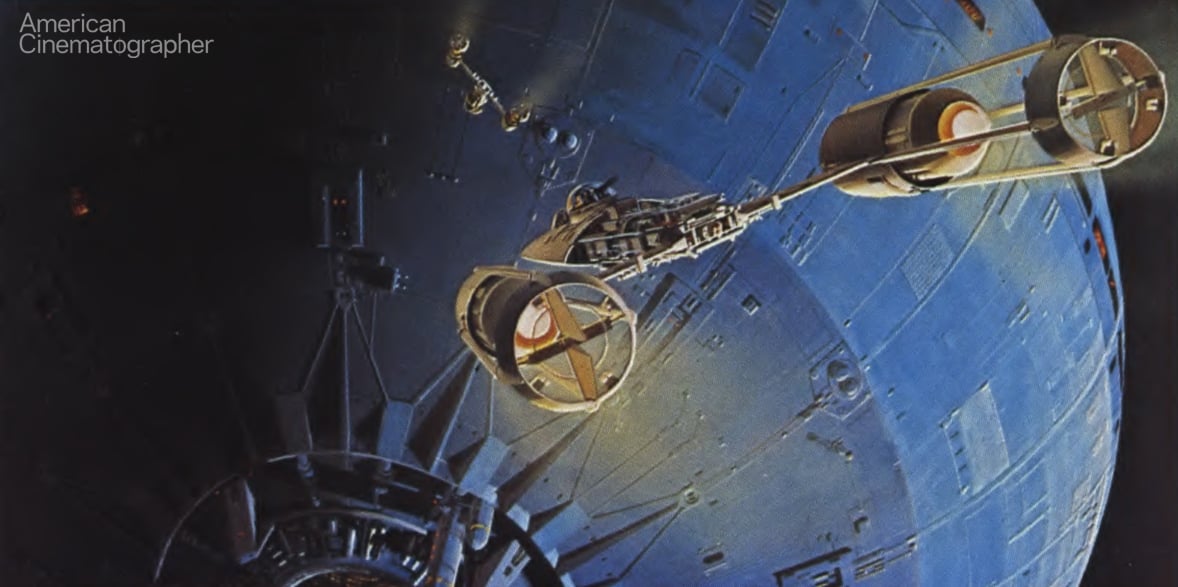

Understandably, conceiving the visuals for such a film would be no small task. Lucas initially gathered around him the talents of Colin Canwell, who had worked on 2001, to design the initial spacecraft models; Alex Tavoularis to do preliminary storyboard sketches of early scripts; production illustrator Ralph McQuarrie to visualize the basic ideas for characters, costumes, props and scenery. Over a period of time Ralph went from simple sketches and line drawings to a handsome series of production paintings which set a visual tone for the production.

"The trouble with the future in most futurist movies is that it always looks new and clean and shiny," comments George Lucas. "What is required for true credibility is a used future. The Apollo capsules were instructive in that regard. By the time the Astronauts returned from the moon, you had the impression the capsules were littered with weightless candy wrappers and old Tang jars, no more exotic than the family station wagon. And although Star Wars has no points of reference to Earth time or space, with which we are familiar, and it is not about the future, but some galactic past or some extra-temporal present, it is a decidedly inhabited and used place where the hardware is taken for granted.

"We were trying to get a cohesive reality. But since the film is a fairy tale, I still wanted it to have an ethereal quality, yet be well composed and, also, have an alien look. I visualized an extremely bizarre, Gregg Toland-like surreal look with strange over-exposed colors, a lot of shadows, a lot of hot areas. I wanted the seeming contradiction of strange graphics of fantasy combined with the feel of a documentary.

Best summed up by Star Wars production designer, John Barry, "George wants to make it look like its shot on location on your average everyday Death Star or Mos Eisly Spaceport or local cantina."

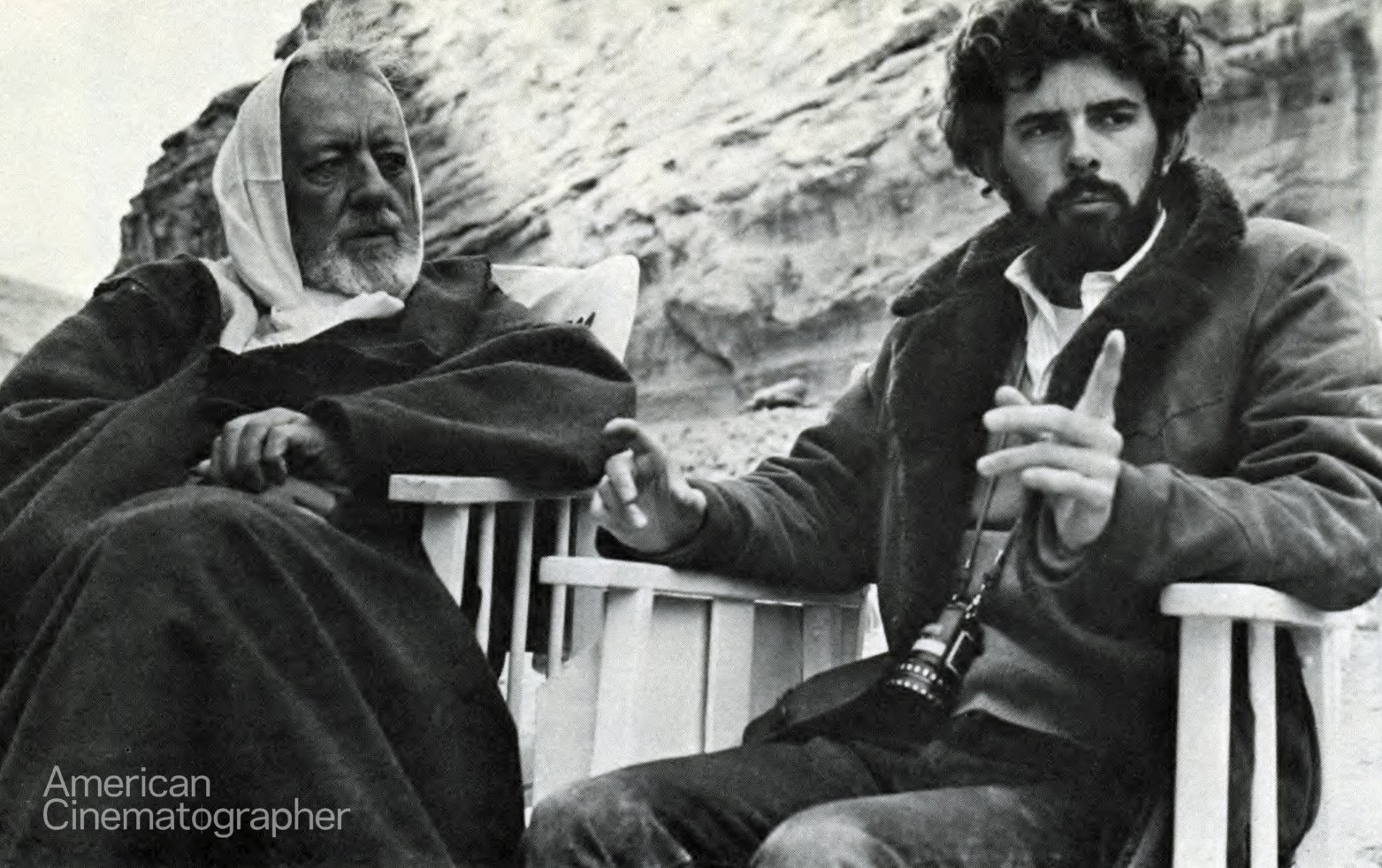

Realizing his needs, George Lucas searched for a more-than-capable director of photography. After considering a number of people, he hired Gil Taylor, basing his choice on Taylor's cinematography for Dr. Strangelove and A Hard Day's Night. "I thought they were good, eccentrically photographed pictures with a strong documentary flavor," says Lucas.

Meanwhile, at Elstree, production designer John Barry and his crew began designing the myriad number of props and sets. Instead of the shiny new-looking architecture and rockets one usually associates with space fantasy motion pictures, the sets and props for Star Wars were designed to look inhabited and used.

The film features more than a dozen robots, but the two major ones are C-3PO, known as 'Threepio', and R2-D2, called 'Artoo'. Threepio was the one robot designed by production illustrator Ralph McQuarrie, art director Norman Reynolds and sculptress Liz Moore. The job of making the other robots work fell to John Stears, who devised the production and mechanical special effects. Besides the dozen robots he built for Star Wars, he also came up with light sabers, land vehicles and a myriad of explosions.

In the meantime, producer Gary Kurtz worked out a budget and logistical plan for the complex job of filming on three continents. For the desert planet, Tatooine, all American, North African and Middle Eastern deserts were researched and explored. In Southern Tunisia, on the edge of the Sahara desert, the ideal locations were found: a dry, arid landscape with limitless horizons filled with bizarre but real architecture.

It was decided the interiors would be photographed in London, England, because of the close proximity to North Africa and also because of the availability of a pool of top technical people at the EMI Elstree Studios, Borehamwood. It was the only studio in England or America that could provide nine large stages simultaneously and allow the company complete freedom to hand-pick its own personnel.

In March, 1976, a film production unit and cast descended on Tozeur, a sleepy little oasis town in Southern Tunisia, where North Africa and Arabia meet, and the Sahara Desert begins. The construction crew worked for eight weeks to turn the desert and towns into another planet. Filming began on the Chotte el Djerid, not too far from Tozeur. Chotte means "salt lake" in Arabic. It was an arid, dried-up wasteland dotted with an occasional palm tree; a bare smooth desert reflecting the sun's rays from its myriad streaks of white salt. It's a place of mirages, where it is difficult to distinguish the real from the unreal. In other words, an ideal setting for a film like Star Wars.

The first sequences of Star Wars take place on Tatooine, a planet in another galaxy. The homestead where the young hero, Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), lives is a huge hole in the ground leading to a series of caves.

Other locations included the sand dunes of the Tunisian desert a few miles outside Nefta. The scene called for the skeleton of a monster creature to lie in the background as robots Artoo-Detoo and See-Threepio made their slow way across the sands. As the sinister Imperial stormtroopers searched for the robots, one of the stormtroopers rode a mammoth beast which looks like a half-dinosaur, half-elephant.

After several sequences were filmed against the rocky grandeur of a volcanic canyon outside Tozeur, the cast and crew moved to Matmata, one of the most unusual towns in the world.

Matmata is largely inhabited by people who make their homes in caves cut from the sides of the crater-like holes in the ground. These craters dot the landscape, much like craters on the Moon. The underground homes evolved not so much in defense against possible enemies many years ago, but as a means of protection from the weather, which is scorching hot in summer and bitterly cold in winter.

The average Matmata home consists of an open central hole, 25 feet in diameter. Often the hole is surrounded by parapets. In this way, there is shade from the sun and protection from the wind. The only entrance is by a gently sloping ramp which leads through a tunnel with recesses on either side for the storage of fodder and produce. The recesses are also used for stabling animals. The courtyard is 20 to 30 feet square and contains cisterns fed by channels from saucer-like depressions designed to catch the rain. There are usually two rooms on each side of the square, gouged from the earth. Inside the roomsor caves niches and recesses act as shelves, seats and beds.

In Matmata, George Lucas filmed sequences in the depths of the Hotel Sidi Driss, which is larger than but still typical of, the local population's dwellings. In Star Wars, the hotel is seen as the interior of Luke Skywalker's homestead.

Following two-and-a-half weeks filming in Tunisia, the Star Wars cast and crew moved to EMI Elstree Studios. It took all nine sound stages to house production designer John Barry's 30 sets of other planets, starships, caves, control rooms, cantinas, and the vast network of sinister corridors on the evil, man-made Death Star. For the enormous rebel hangar sequence filled with a squadron of X-wing and Y-wing fighters, the set was so huge that it had to be filmed on the largest sound stage in Europe, located at Shepperton Studios, in Middlesex, some twenty miles away. The scenes with the actors took 14 and one half weeks to film in England.

The script called for a large number of miniature and optical effects. In June of 1975, George and Gary contacted John Dykstra with regard to his supervising the photographic special effects. No commercial facility had the equipment or the time to accomplish what Star Wars required, so John worked out the plans for a complete in-house effects shop. Appropriately named "Industrial Light & Magic Corporation," the shop was set up in a warehouse in the San Fernando Valley.

Employing as many as 75 people and, in post-production, working on two full shifts, ILM executed the 360 separate special-effects shots in the film. Altogether, film enhancement and special effects are visible for half of the running time of Star Wars.

The various departments at ILM included a carpentry shop and a machine shop, which had to build or modify the special camera, editing, animating and projecting equipment required for the special effects. A horizontal 35mm double-frame format was utilized on all the special effects filming in order to get a larger negative that could sustain the quality of the images filmed in live action. A model shop was built to execute the prototype models of the various space and land vehicles.

Other departments included optical printing for putting multiple images together on film, and a rotoscope department, which provided matte work and also generated original images to be used in explosion enhancement. The electronics shop devised special cameras for a self-contained camera and motion control system. There was also a film control department for filing and coordinating all of the special effects and other film elements.

Additional second unit Tatooine desert material was photographed in Death Valley and Yavin Jungle material was photographed in the Mayan ruins of Tikal National Park, Guatemala.

Noted composer John Williams spent a year preparing his ideas for the score. During March, 1977, he conducted the 87-piece London Symphony Orchestra in a series of 14 sessions in order to record the 90 minutes of original music.

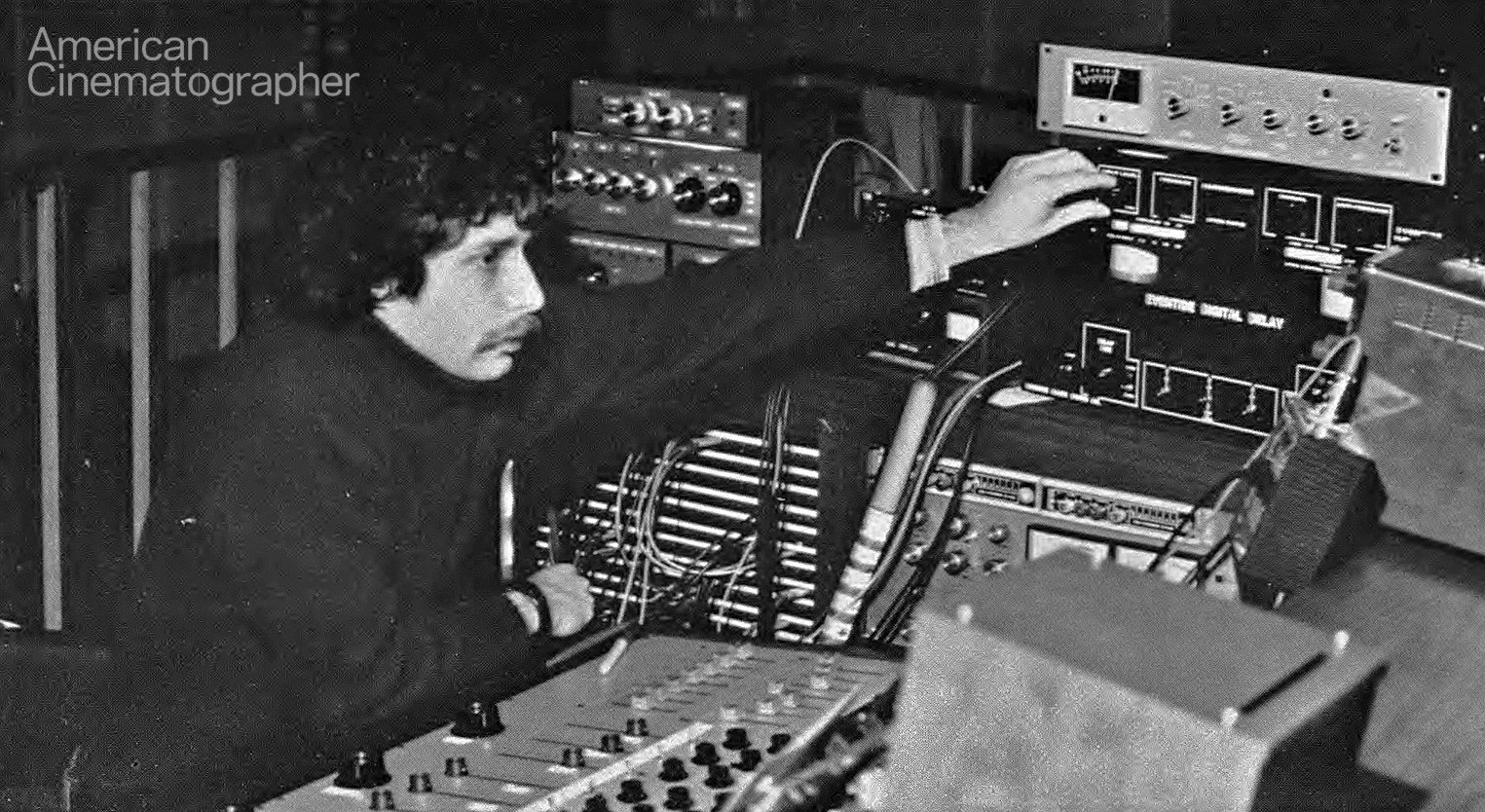

Original sound effects for the galactic languages, vehicles, robots and weapons were collected and created by Ben Burtt. The final elaborate stereo soundtrack was mixed at the Samuel Goldwyn Studios, using the Dolby system of noise reduction for the ultimate motion picture high fidelity in the theater.

ABOUT THE FILMMAKER...

During the last few years, there has emerged within the motion picture industry, a whole new generation of talented filmmakers. These young directors were brought up on motion pictures and television. They extended their childhood passions for the film medium by attending film schools. They studied theory, explored the technical demands of motion pictures by making their own short films, and endlessly viewed past works in an endeavor to rediscover those visual and narrative elements that made movie-going a weekly habit around the world. Their own work has exhibited a sense of craft, intelligence, youthful enthusiasm and a willing capacity to entertain audiences.

In the forefront of this new generation of filmmakers is 33-year-old George Lucas, who directed and co-wrote the enormously successful and critically acclaimed American Graffiti. It was hailed as the quintessential movie about American teenage life and rituals when it was released in 1973. In direct contrast to that subject matter, Lucas has now written and directed Star Wars, an action-filled space fantasy.

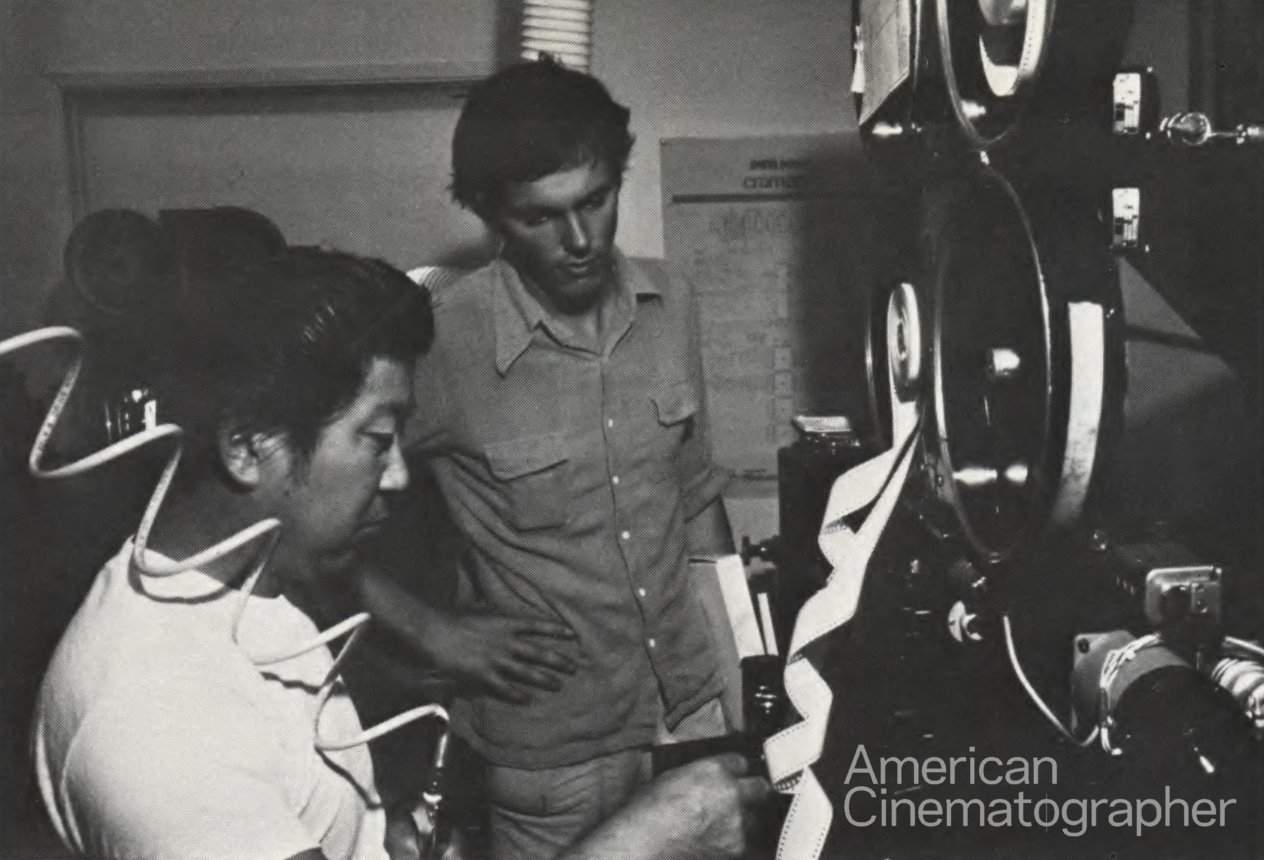

George Lucas attended the University of Southern California Film School, where he quickly turned out eight films. He subsequently became a teaching assistant at USC for a class training U.S. Navy cameramen. With half the class assisting him, he made a science-fiction short entitled THX 1138: 4EB. The film won top honors at the Third National Student Film Festival in 1967-68 and many other awards.

In 1967, Lucas was one of four students selected to make short films about the making of the Carl Foreman film, McKenna's Gold. Lucas' short was Foreman's favorite, although it told more about the mysteries of the desert than about Foreman's film. He then won a scholarship to Warner Bros. to observe the making of Finian's Rainbow under the direction of Francis Ford Coppola. While working as Coppola's assistant on The Rain People, he made a forty-minute documentary about the making of the movie entitled Filmmaker, which has been recognized as one of the best films on moviemaking.

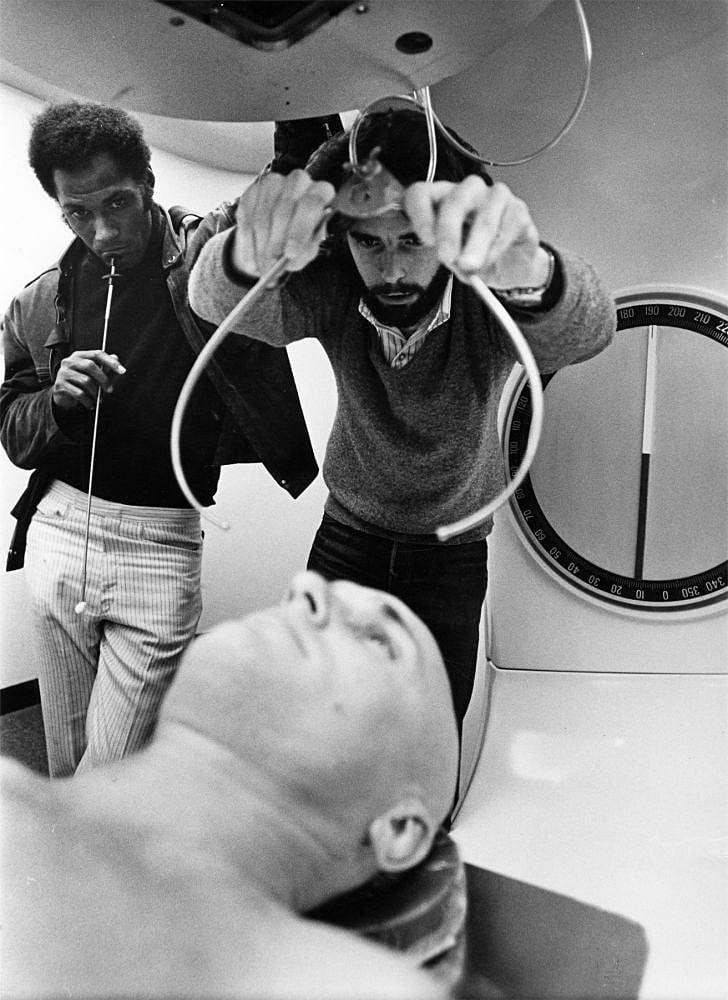

George Lucas' first professional feature motion picture was THX-1138, which was an expanded version of his prize-winning student film. Francis Ford Coppola acted as executive producer on the film. Starring Robert Duvall and Donald Pleasence, THX-1138 was enthusiastically received by critics when it was first released and has since become a cult favorite among audiences.

In 1973, Lucas co-wrote, with Gloria Katz, and Willard Huyck, and directed American Graffiti. Gary Kurtz and Francis Ford Coppola co-produced. The movie was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Screenplay. It won the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture Comedy, and both the New York Film Critics and the National Society of Film Critics Awards for Best Screenplay.

George Lucas was born on May 14, 1944. The son of a retail merchant, he was raised on a walnut ranch in Modesto, California. His two passions as a teenager were cars and art. Determined to become a champion race car driver, he worked at rebuilding cars at a foreign car garage. He also worked in pit crews at races throughout the country. Following a serious automobile accident a few weeks before his high school graduation, he gave up any hopes of becoming a race car driver.

He attended Modesto Junior College for two years and majored in social sciences. By chance he met cinematographer Haskell Wexler, who encouraged him to study filmmaking and helped pave the way for his admittance to the University of Southern California Film School.

George Lucas met his wife, Marcia, when she was hired to assist him on editing a documentary under the supervision of Verna Fields. They live in San Anselmo, California. Marcia Lucas was one of the editors on Star Wars and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Editing with Verna Fields for American Graffiti. She has also edited Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore and Taxi Driver.