The Cinematographer and the VAD

“With the expanding use of virtual production, it is essential that the cinematographer be on the production’s prep schedule earlier than they would normally be hired for traditional prep.”

The cinematographer’s creative partnership with the production designer and art department is critical for a successful production of any kind. They consult with each other on the sets, colors, textures, integrated practical lighting and so forth. With virtual production — and, more specifically, projects employing in-camera visual effects (ICVFX), i.e., LED-wall environments — there is a hybrid of a physical (practical) art department and a virtual art department, or VAD.

Those in the physical department tend to the traditional set needs required on every production, while the VAD crew handles the elements of the sets/backgrounds that appear on the LED walls in the virtual space. The virtual realm requires just as much production design, art direction, set decoration, props creation, set construction, painting and texturing as the practical one, and these elements must be created to match the practical art department’s work in scale, color, texture and dimensionality.

With the cinematographer, the physical art department and the VAD all working in unison, their collective achievement is the practical world on the physical stage blending seamlessly with the virtual world rendered on the LED wall, so that the audience cannot tell one from the other.

Focus on Prep

In traditional composite work that incorporates blue- or greenscreen, virtual elements are created by postproduction artists long after photography is completed. This means that on set, the cinematographer must make an educated guess about how to light and compose their photographic elements to match what will be made later. In ICVFX and virtual production, it’s the opposite: All virtual elements are made before shooting so that they are available on set and can be photographed simultaneously with the practical elements (including actors) with the goal of producing a final in-camera composite that happens live.

This has significant benefits, not least of which is that it eliminates the guesswork involved with blue- and greenscreen photography and gives the cinematographer and director more precise — and on-set — control of the image. But it also requires significantly more work to be done in prep and, ideally, less in post. This prep work includes not only the construction of digital assets, but the physical assets as well. The traditional art department must craft bespoke set elements, props and dressing far in advance of photography — because these physical items need to be designed, approved and constructed with ample time for them to be scanned and then reproduced in the virtual world. This is a key step that enables virtual props and set dressing to match real-world items, making the transition between the two unnoticeable to the audience.

This also puts the onus on the production to hire prop teams, construction teams and set decorators much earlier than usual. It requires constant communication between the virtual and practical art departments — as last-minute shopping for props or set dressing would create significant issues for the virtual department, and, conversely, virtual artists can’t just incorporate stock items into a scene (such as furniture and lighting fixtures) if there must be a practical matching component.

This workflow also dictates that decisions affecting cinematography — including practical lighting, placement and size of windows, direction and intensity of sunlight, etc. — must be made very early in preproduction.

As Michael Goi, ASC, ISC — who served as director of photography, executive producer and producing director on the Netflix series Avatar: The Last Airbender (AC July ’24) — expressed to me in a recent correspondence, “With the expanding use of virtual production, it is essential that the cinematographer be on the production’s prep schedule earlier than they would normally be hired for traditional prep. The cinematographer who will shoot the film would ideally also be the person who photographs or helps design the assets to be used on the LED screen in order to ensure that the placement of the sun, or another main light source, is in a position which will make lighting the volume sets conducive to achieving the mood and efficiency the production requires.

“Virtual-production assets, even those that were photographed rather than built in the computer, need to have the cinematographer adjust color and contrast before they get sent to the volume for uploading,” he continued. “So, the cinematographer’s schedule needs to include non-consecutive prep for the purpose of being able to contribute to these foundations of the visual approach to the project.”

Safeguarding the Production

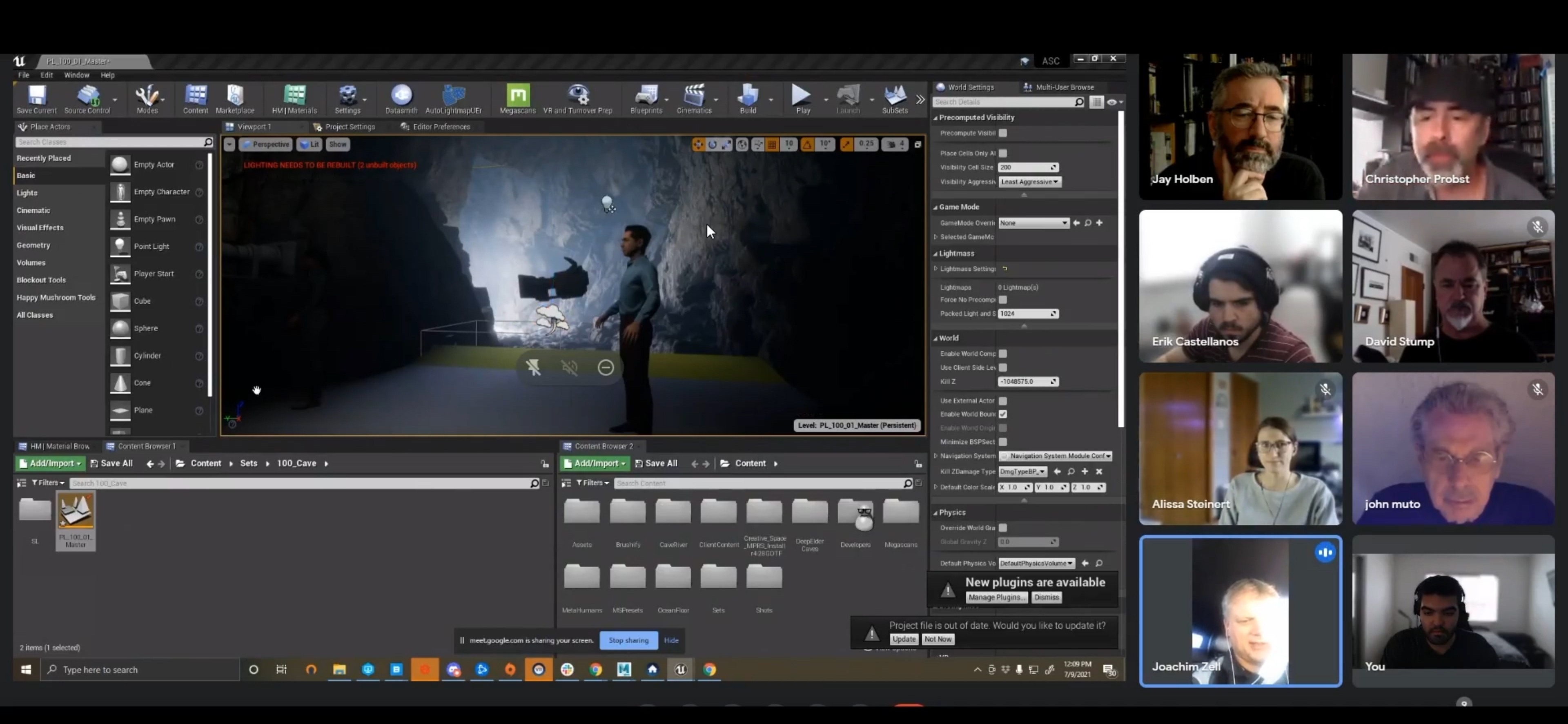

Christopher Probst, ASC has photographed more than 20 ICVFX projects, and he taught a seminar on virtual production for the ASC Master Class earlier this year. He is the chief innovation officer and co-owner at Synapse Virtual Production in Los Angeles, which operates its own LED ICVFX stage and consults with and facilitates other LED stages as well. Probst and I spoke recently about the cinematographer/VAD relationship.

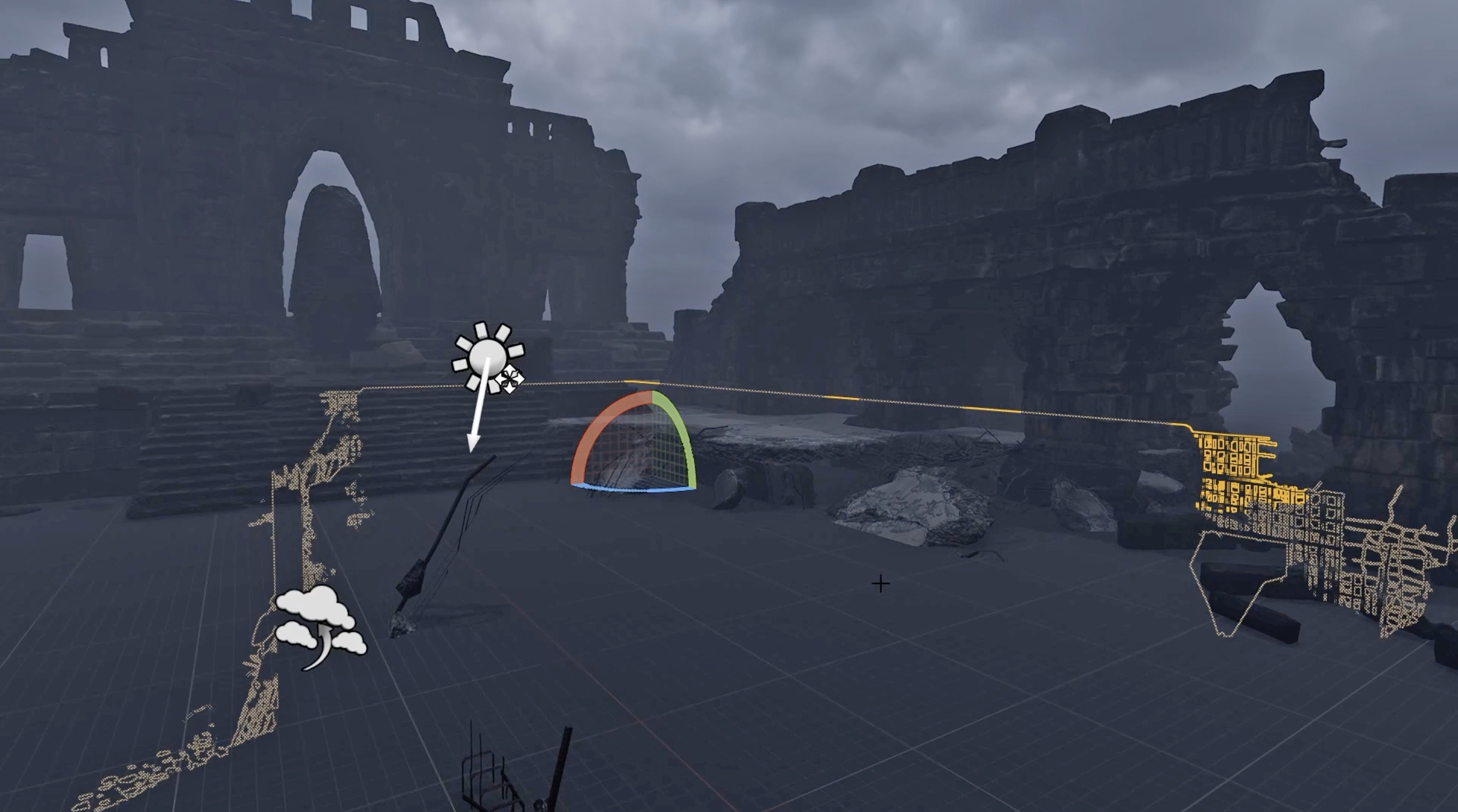

“When shooting at a practical location,” he says, “the cinematographer typically scouts and looks at the time of day for optimal shooting, the angles and directions you want to shoot, and also assesses any existing practicals that can be utilized — all of that still applies with virtual production. There can often be several sessions where the director and cinematographer work with the VAD team and are able to virtually scout the various 3D environments being created. Ideally, this is when a cinematographer can add input into what angles may be shot, how that scene is lit virtually — and will ultimately tie into how the practical set is lit.

“In the ideal workflow, the cinematographer will have collaborated with the artists in preproduction, added their input and taste to lighting the scenes, and solved any potential pitfalls then.”

“Maybe you ask for a window on one side of a set because you know you’ll have a character staged at the table, and with that window over their shoulder, you’ll have cool daylight on one side and can add a virtual sconce with a warm glow on the opposite wall, introducing color contrast in the virtual world that you can extend into the practical world with on-set lighting. As a cinematographer, I’m going to know the best position for that window and the height of the sconce, because I know the shots we’re going to do.

“So, when prepping or consulting on a virtual-production project, my job as cinematographer is to help solve any potential points of failure and safeguard the production — I don’t want anyone’s production to go bad on VP. Part of the vetting process of any VP asset is to make sure that it will be performant when it comes to production. For example, Unreal Engine has massive power to create intricately detailed worlds and photorealistic environments, but the ray tracing and rendering need to happen in real time at a target frame rate. It’s one thing when you’re looking at an environment on a computer in the VAD, but it’s another thing when you’re looking at it in a big LED volume. It might be hitting 24 frames per second in the VAD, but when you put it on the wall, suddenly it may only hit 10 fps. So, I try to make sure that the artists are optimizing their loads for at least double the frame rate we need. This means if we are shooting 48 fps on set, then I need the load to be able to hit 96 fps to make sure we get that target on stage.

“Now, it’s not necessarily the role of a cinematographer to know how to optimize VP assets in Unreal Engine, but I know that a wall sconce with a 25-watt bulb, in the real world, isn’t going to give me any significant output 50 feet away — while in a virtual environment, Unreal Engine doesn’t know that. And unless you tell it otherwise, it will trace the rays of light from a virtual bulb 300 or 1,000 feet away! The virtual artists creating the assets should know to tell the Unreal to curtail the light from that fixture to stop the engine from having to overanalyze the ray tracing and help that environment run more efficiently, but it never hurts to know how the lighting you’re asking for in the virtual space impacts the performance of an asset.

“In the ideal workflow, the cinematographer will have collaborated with the artists in preproduction, added their input and taste to lighting the scenes, and solved any potential pitfalls then. The problem is, oftentimes, the Unreal Engine operators on the set are not the artists who created the asset, so they’re left to scramble and try to understand how it was made and how to fix problems on the fly.

“Virtual production is such a revolutionary technique and technology. And when everything performs, it can be absolutely mindblowing — when you see that cinematographic sleight-of-hand that you’re able to pull off with what is effectively a big TV screen behind someone’s head. That’s an oversimplification of what virtual production is, but the takeaway from all of this is that with this technique, the cinematographer is once again truly the author of the image — how bright or dark it is, how warm or cool, how much atmosphere is on the set. You see it all happening in camera, as opposed to being surprised by the final work done by the VFX artists three months down the line.”

Meaningful and Early

It behooves the cinematographer to become familiar with the tools of virtual production, and how they can better optimize the image through virtual lighting and textures — and anticipate potential trouble spots before production begins. And it follows that productions incorporating ICVFX must ensure that the cinematographer has meaningful input in early decisions to facilitate a smoother production.

Jay Holben is AC’s technical editor and an ASC associate member. He served as technical documentarian on Season 1 of The Mandalorian and has subsequently worked in numerous ICVFX environments, including as director of the ASC MITC StEM2 short film The Mission.

He is also the author of the books American Cinematographer’s Shot Craft: Lessons, Tips and Techniques on the Art and Science of Cinematography and Lessons From American Cinematographer. He is also co-author of The Cine Lens Manual with Christopher Probst, ASC.