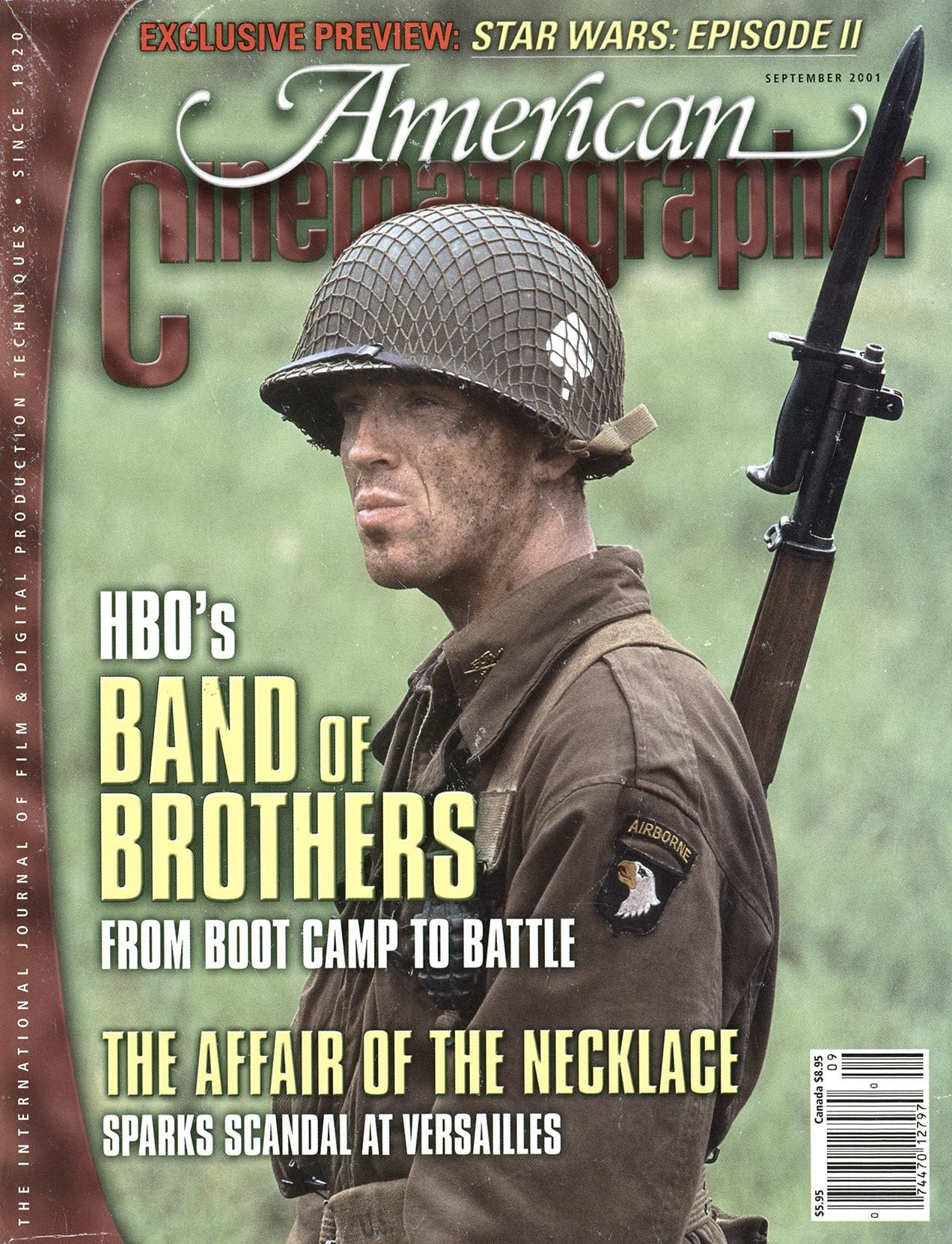

Close Combat: Band of Brothers

HBO’s intense 10-part miniseries, shot almost entirely in England, examines global conflict from the foot soldier’s perspective.

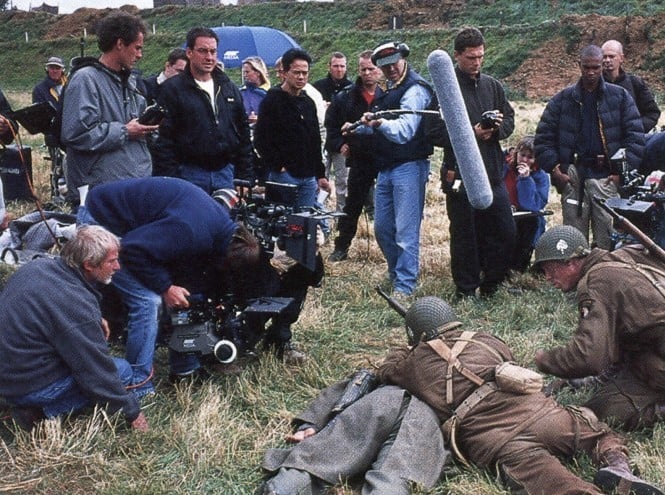

HBO’s World War II miniseries Band of Brothers transports viewers to the front lines in brutally realistic fashion as it follows a single company of U.S. soldiers from their training in America through their first year of combat in Europe. The firepower was so intense at times — and the danger seemed so real — that even members of the crew forgot they were making a movie. Recalling a particularly harrowing sequence, director David Frankel says, “I was running with the camera operators as our guys charged a German-held village. There was a German machine gun high up in a church tower, and our guys were like fish in a barrel. Blanks sound as loud and scary as the real thing, especially when you’re seeing men go down and the officers are still sending more in.

“At one point a soldier got hit and another guy ran out to rescue him. The camera operator was supposed to follow the action, but as he started to move forward he became so alarmed that he hid behind the actors. His instinct was, ‘Oh God, they’re shooting at me.’ Needless to say, we had to cut. That was the moment when I felt what the horror of battle must be like.”

“A much-used phrase was: ‘Like dropping a documentary unit into the past.’

That was the approach.”

— Remi Adefarasin, BSC

Band of Brothers focuses on the men of Easy Company, immortalized by historian Stephen E. Ambrose in his nonfiction bestseller of the same title. As members of the 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, they were among the first American paratroopers trained for the war. When Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg decided to produce a TV miniseries that would honor the hundreds of thousands of “citizen soldiers” without whom World War II could not have been won, they turned to Ambrose’s book.

At a cost of $120 million, Band of Brothers is the most expensive original programming venture in HBO’s history, as well as its most ambitious. Production on the 10 episodes, all of which were shot in England with the exception of a few scenes in Switzerland, began in April 2000 and wrapped eight months later. Academy Award-nominated cinematographer Remi Adefarasin, BSC (Elizabeth, The House of Mirth) and Canadian cinematographer Joel Ransom, CSC (The X-Files, Harsh Realm) split the 10 hour-long dramas between them. They shot simultaneously, and each had their own crew.

The producers wanted the same type of realistic look and feel that Spielberg brought to Saving Private Ryan (AC Aug. ’98). “[They were after] that same kind of heightened contrast and lowered saturation,” affirms Adefarasin. “A much-used phrase was: ‘Like dropping a documentary unit into the past.’ That was the approach.”

The latest post-production techniques were used to get a truly authentic look; the show’s 35mm footage was scanned as 2K digital data that was color-timed at Kodak/Cinesite’s digital mastering lab in London (see 'Virtual Coloring' at the bottom of this article). “Steven [Spielberg] didn’t want to get into the long-lens, high-speed, backlit feel, because that would have been too romantic,” Ransom explains. “He didn’t want to beautify war.”

ambience would be added in post.

There were a few other ground rules: minimal use of cranes, German POV shots and slow motion. “I think Steven wanted the series to reflect the American soldier’s subjective experience,” theorizes Frankel, who was one of eight directors on the project. “That meant [making it] experiential for the audience as well. By using a crane — in effect, stepping back and seeing things in context — you make it too objective. There were exceptions, of course, when it was important to have the height of a crane or to be able to manipulate the camera into certain positions.”

The majority of the combat footage was shot handheld. Ransom estimates that 90 percent of these scenes were shot with 45- or 90- degree shutters, a technique that Janusz Kaminski used in his Oscar-winning work on Private Ryan. Reducing the shutter angle has the effect of making action sequences punchier. “It gives a staccato effect to panning shots, and it pixilates explosions,” Ransom elaborates.

The first major fighting sequence occurs in Episode 2, which was shot by Adefarasin and directed by Richard Loncraine. The scene shows Lt. Dick Winters (Damian Lewis) hunched over to avoid being shot as he runs down a long trench. Bullets zing by just above his head. The camera precedes Winters as he runs, catching him first in wide shot and then in a tight close-up of his face. A-camera operator Martin Kenzie recalls, “Our problem was the width of the trench and the length of movement it required. All of the usual tools you might use for that type of shot — dolly, quad bike, wheelchair — were too wide and not maneuverable enough for some of the tight corners. Running might have worked if it hadn’t been necessary to run backwards.

“Joel Ransom came up with the idea of using a rickshaw, and special-effects supervisor Joss Williams and his men built it and made it work. They took two bicycle front-fork assemblies, built a frame with a seat and attached [about 15"] cycle wheels. The handles were extended at the front so that dolly grip John Arnold could run forward, pulling the rickshaw. He was doing all the hard work while I sat in the seat, facing backward, with a Moviecam SL [fitted with a 32mm Zeiss Ultra Prime lens] in my lap. At one point, John parked the rickshaw in a siding, skillfully tipping me off [as I stayed on Winters], who I then began following from behind.”

To facilitate the work and avoid possible injury, Adefarasin encouraged his operator to use a liquid crystal display (LCD). “Using an onboard LCD monitor as a Viewfinder’ eliminates the need to keep your eye squeezed against the eyepiece, which is difficult during vigorous operating,” the cinematographer explains. “Mounting the screen to the front of the camera also helped when we had to move quickly to keep up with the troops. It also enabled us to do very low running shots without complicated rigging.”

England recorded its wettest year in history last year, and the constant rain posed its own set of hazards. “The trenches got waterlogged, and we had to keep pumping the water out,” Adefarasin recalls. “The mud was unbelievable! On the very first day of the shoot, I was helping to push a camera trolley up a muddy slope. Ben Wilson, my A-camera first assistant, was in front pulling, and he slipped in the mud. He didn’t even scream as I pushed the trolley over him.” (fortunately, the soft mud gave Wilson a cushion.)

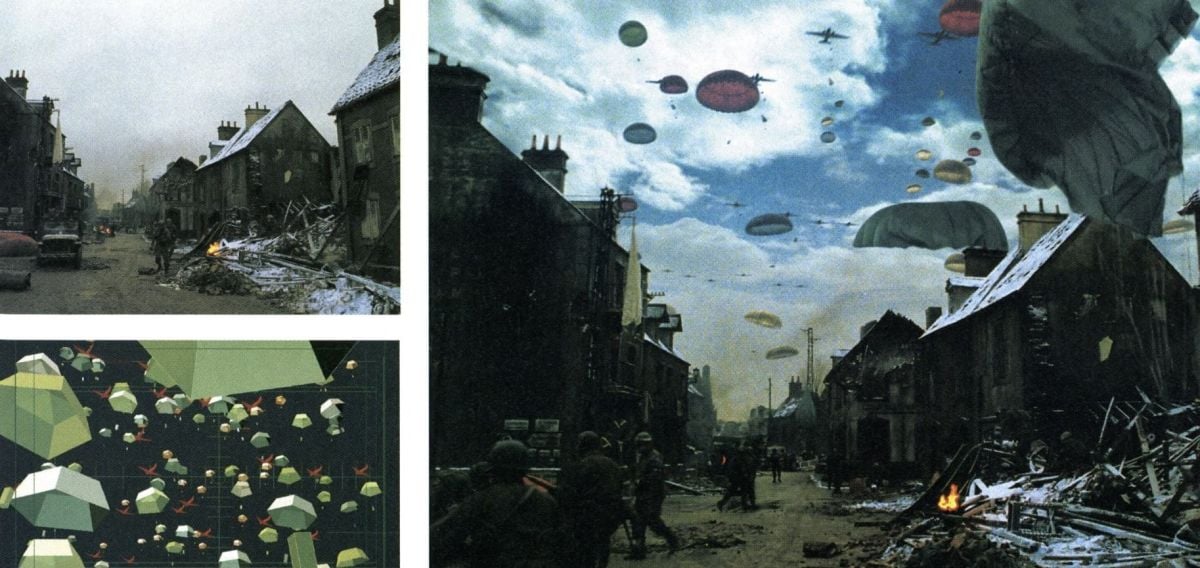

Episode 2 opens with one of the most nerve-rattling sequences in the entire series: Easy Company’s parachute jump into the Normandy countryside in the pre-dawn hours of D-Day. It was the company’s first combat jump and first taste of war.

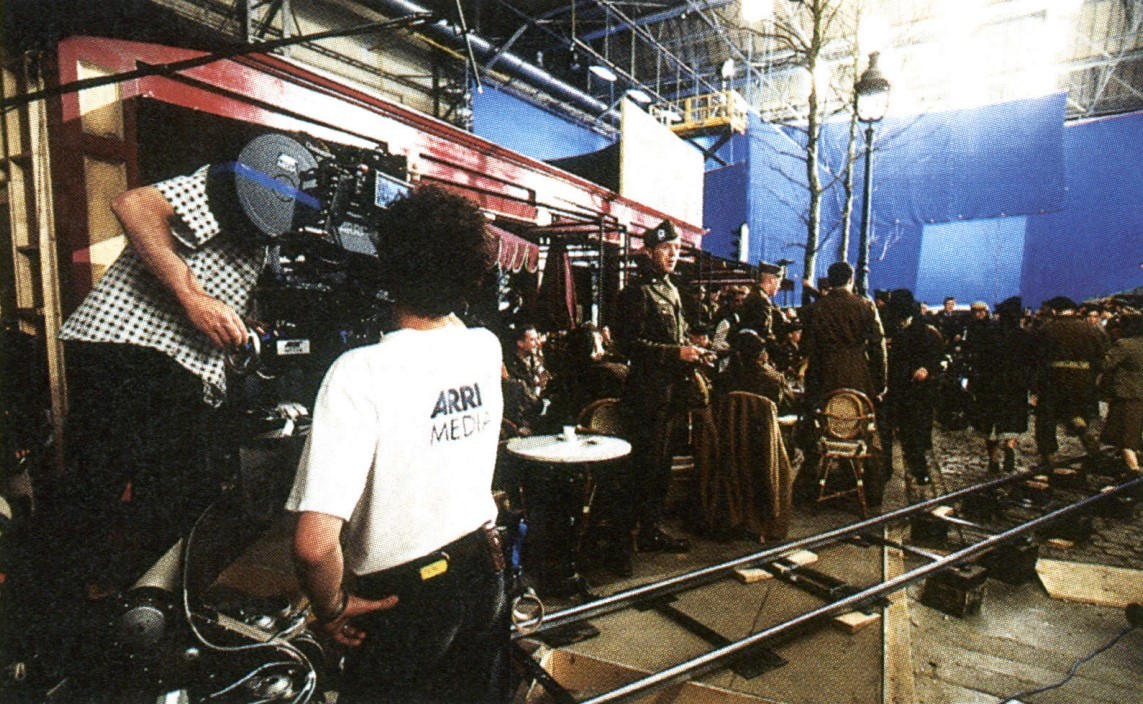

To film the sequence, the production managed to find a mothballed C-47 plane. Crew members removed its wings — partially to eliminate some of the weight and partially because they wouldn’t be seen in any shots — and refurbished the interior. All but one of the interior C-47 scenes were shot inside the aircraft, which was housed inside one of two giant airplane hangars that were being used by the production as soundstages. The hangars were located at the former British Aerospace Aerodrome in Hatfield, England, some 30 miles outside London. The site, which the crew affectionately christened Hatfield Studios, also included a backlot where many scenes were filmed.

In order to suggest the bounce of typical aircraft movement, the crew placed the plane atop two separate motion rigs, which sat one on top of the other. Each rig produced a different kind of shaking and jostling. Directly beneath the aircraft was the first rig, an air platform consisting of a steel frame and 16 small air bellows. The plane “floated” on the bellows, which were round rubber units about 8" wide. Each was filled with a small amount of air, and over a wide area they provided tremendous lifting power.

Deflating and inflating the bellows very rapidly created a strong vibration. To produce an even stronger movement — an out-of-control tilting for moments when the plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire — the air platform rested on a gimbal positioned on the hangar floor. It could tilt 20 degrees in 2½ seconds, an extraordinarily fast movement considering that the plane’s fuselage was 45' long. The hydraulic system that controlled the gimbal was operated manually. “You only need computer control if you have to repeat the exact same movement, and nothing was so tied-in that we had to have the plane in exactly the same position twice,” explains special-effects supervisor Williams, who devised the dual rig.

Inside the fuselage, two rows of soldiers sat facing each other on benches. As the German fighter planes “attacked,” filling the outside air with explosions and flak, the C47 reacted violently. “Those scenes were hell to shoot,” acknowledges Adefarasin. “We all came away with bruises. In fact, the shaking was so fierce at times that we had to use Hot Gears.” It was in anticipation of just such circumstances that Adefarasin had suggested renting Hot Gears in the first place. “It’s a very clever device that controls a geared head and can save the operator from injury,” he comments. “It’s also great for very awkward shots that are physically difficult. Its main beauty is that it’s relatively cheap, so you can keep it on standby.”

Williams came up with a clever idea for making it appear as though flak was breaking the sides of the aircraft, right by the heads and bodies of the actors. He cut square pieces out of the aluminum fuselage and replaced them with pewter sheeting. When compressed air was blown into the pewter from outside the plane with several speciallyrigged 40- to 50-pound pressure canisters, it created small holes that, given the circumstances, appeared to be flak, especially as the pewter peeled back when the shrapnel penetrated the plane.

The plane’s pitching and rolling proved especially troublesome for focus puller Wilson, who wound up working almost entirely with the Arri LCS remote-focus system. According to operator Kenzie, “It’s much easier to work with a remote-focus device when operating handheld. It also keeps Ben and me out of each other’s way, especially since the inside of the C-47 was incredibly cramped.

“The Moviecam SL was our best friend throughout the shoot,” Kenzie continues. “It’s a very light and adaptable camera. Ben had some brackets made up, and by using the Arri Blue Handle system, we could quickly change between three handheld modes: conventional shoulder or high mode; low angle, backache, monitor-watching mode; and midheight mode, when most of the camera is under your arm.”

In addition to two SLs, each production unit had an Arriflex 535B. It wasn’t unusual for all three cameras to be pressed into service at once; at times, as many as seven cameras were running. Lenses included a full set of Zeiss Ultra Primes (18mm to 180mm), a Canon 300mm, and Cooke 25-250mm and 20-100mm zooms. Arri Media in London supplied the cameras and lenses and “provided superb support,” according to Adefarasin. The cinematographer also praised the lighting rental house, Lee Lighting.

Night sequences aboard the C47 proved particularly tricky to light because of a historical fact: no lights were allowed on inside the aircraft during the war, lest they give away the plane’s position to the enemy. While the production cheated a bit by using a tiny Lightstream torch held by the cinematographer inside the aircraft, these scenes relied primarily on units set up outside the plane, which, between the gimbal and the motion rig, sat some 20' above the floor. Par cans and 10Ks were attached to a jib arm mounted on a separate gimbal, so that the lights could be moved up and down and not in concert with the plane’s movements. Gaffer Jimmy Wilson augmented the illumination with three Lightning Strikes units and some 1K Pars, the latter representing flak.

According to Adefarasin, it was difficult to keep light coming through the plane’s small windows with any regularity. “We had to find angles that would make the light work when the plane moved, but still look ‘real.’ We placed the Lightning Strikes units at different angles. I feel it’s important that they don’t always look the same brightness or color, so we varied the intensity and color. Full, half and quarter CTOs were used, and a frame of .6ND was waved in front of two of the lightning units to create a more organic feel.”

Remi Adefarasin,

BSC (left) poses

with two key

members of his

crew: longtime

gaffer Jim Wilson

and rigging

gaffer Barrie

More.

After being struck repeatedly by anti-aircraft fire, another plane suddenly bursts into flames and begins to dive. A fireball tears through the cabin from front to back, an effect created with a propane flame projector. Two cameras were locked off in the tail section, filming the fireball as it hurtled straight toward them.

The challenge Adefarasin faced was “having enough light in the plane so that when the ball lit up, there would be enough stop to hold the textures in the flame. I shot it on Kodak [Vision 200T] 5274 stock at around T8. We lined the rear wall of the C-47 with heavy-duty aluminum foil to throw light back onto the stunt men’s bodies. We used some older Zeiss lenses and optical flats, just in case.”

In addition to the 5274, Adefarasin used Vision 500T 5279 and Vision 800T 5289 on the show. He and Ransom chose the same film stocks, though each arrived at his decision independently. Ransom considered using Fuji stock on the first episode, the only one set in the United States (although it was shot in England). Ultimately, however, he decided that the difference would be so subtle — especially given what digital colorist Luke Rainey could do in post — that he stuck with Kodak. Between the two units (and a model unit headed by cinematographer Nigel Stone), two million feet of film was exposed during the production.

Episode 7, which documents the Battle of Foy, was one of the most combat-intensive episodes in the series. Shot by Ransom and directed by Frankel, it was set during the winter of 1944-’45. The men of Easy Company were literally living in foxholes outside Bastogne, and they were short on food and ammunition and had no winter clothing. One-third of the episode was filmed on exterior locations, and the rest was shot on a woodland set designed by production designer Tony Pratt. The faux forest, which was also the setting for most of Episode 6, filled an entire hangar at Hatfield Studios.

The hangar was a 300-square foot building that stood 50' high, and the forest set filled the entire structure. It took four weeks to dress the set, which consisted of several hundred real pine trees and 250 trees built by the special-effects department. A painted backdrop covered all four walls of the hangar. The hangar floor was covered with thousands of tons of dirt in order to create a raised forest floor. At a depth of 5', the dirt carpeted the entire set, stopping some 10-15' from the painted backdrop. Railroad ties, stacked one on top of another and camouflaged with dirt, created a kind of restraining wall around the manmade forest floor. It was there that electricians hid 2K and 5K lights aimed directly at the painted backdrop.

American Cinematographer's set visit coincided with the filming of Episode 7. The forest set was breathtaking, both artistically and from a lighting standpoint. Gaffer Wilson, who has worked with Adefarasin for 12 years, was brought in early to design and rig a full lighting grid that would cover the entire ceiling of the hangar. Wilson’s first concern was weight: the hangar was 50' high but had only one central support, so the lighting gantries had to be tied into the building’s existing steel work. It took rigging gaffer Barrie More five weeks to build the grid, and another several weeks to hang the lights.

“We decided to light the forest canopy with 500 space lights, each of which had two feeds, in order to give us three light levels — 1,600 watts, 2,400 watts and 4,000 watts — each with quarter bottom diffusions,” Wilson details. “All of the perimeter space lights had black skirts, while the interior lights had white ones. We lit the painted backdrop with 2K and 5K Skypans, which again gave us three light levels [for day, dusk and night scenes].

“Backlight and top sunlight were generated by 100 CP-61 Par cans, 30 CP-61 Maxi-Brutes, and eight quarter Wendies, all of which were on dimmers and could be moved around the grid as needed. Power was supplied by four 1.2-megawatt Aggreko blimped generators, one in every corner of the hangar. Each one had a 1,000-gallon fuel tank that had to be refilled every two days.

“We ran a total of about 26 miles of cable. To enable us to work quickly and to change from day to night conditions, we had a four-man crew on the top of the grid at all times and a six-man crew on the forest floor. The first problem we discovered was that standing among 500 snow-covered trees and trying to relate a position to the grid crew was difficult. We therefore made a numbered grid system and communicated by radio, which worked great.”

tracks help the

crew guide the

camera past a

tank, which

rolls over a

sturdy wooden

track.

For daytime scenes, Ransom moved 12x12' bounces around and aimed 5Ks or 10Ks into them. For some nighttime sequences, he turned off all of the grid lights and simply illuminated the painted backdrop to achieve a sense of depth. He put smaller lights — Peppers, 300s and Babies — on the actors.

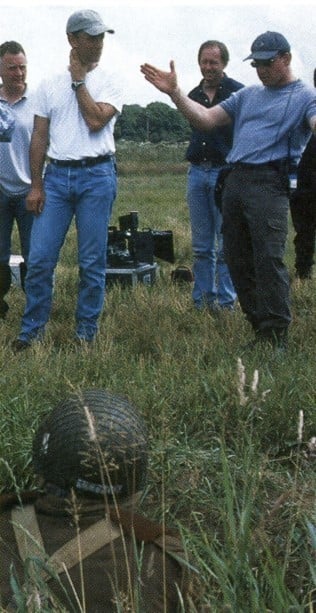

One scene late in Episode 7 finds the Americans charging out of the woods, barreling down a hill and storming the nearby town of Foy, where the Germans are holed up. It sounds simple enough, but the sequence required shooting in three separate locations: in the forest set, on the backlot, and in a real pine forest located about 20 minutes away from the set.

The shots of the soldiers walking through the woods prior to the assault were filmed on the forest set. The shots of the men running out of the woods and down the hill, however, were filmed in the real forest. The camera operators were located on the side of the hill, filming the men as they charged out of the woods and down the hill. For the actual assault on Foy, cast and crew moved to the backlot, where the town had been recreated. The cameras were now behind the Americans, revealing their POV as they ran toward the town. It took three weeks to film the entire sequence. “We had to make all three locations look like one place,” says Ransom with a laugh. “For me, the most difficult aspect of the entire series was waiting for the clouds to gather and give us a soft, even light.”

To help foster the illusion that the activities were all taking place at one site, certain landmarks were carried from one exterior location to the next, so that in either direction the soldiers (and viewers) looked, they’d see the same haystack or house. “It worked pretty seamlessly,” marvels Frankel. “We decided to do it that way because the backlot had no pine trees at the top of the hill, and it was important to see our guys come out of the forest because we had spent so much time with them in the forest. The alternative would have been to create the forest with visual effects, but I didn’t have great confidence in that because it would have limited the number of times we could see the men streaming out of the woods. There are only so many CGI shots that can be budgeted!”

Maintaining a consistent look wasn’t easy, and not simply because the camera was moving from natural light outdoors to the interior of a studio. A second consideration was that Ransom knew he would be shooting with 45-and 90-degree shutters. In the end, he decided to push the 500 stock one stop. “I knew I was going to need the extra stop to go with the shutters and/or any [non-standard] speeds we might decide to use. Pushing the stock one stop brought me up to 1,000 ASA, which introduced a consistent level of grain throughout the entire episode.”

The attack scene was shot with five cameras. “The base stop at the standard 24 fps/ 180-degree shutter angle was T5.6 V2, but shooting with a 45-degree shutter took it down two stops to 2.8 V2.1 didn’t want to shoot at 5.6 V2 in the studio unless we really needed the stop, like for a really long lens shot, so I would ND it down. When we did regular scenes with the shutter at 180 degrees, I would just ND it down to 2.8 V2. On the wider shots I’d let focus pullers Sean Connor and Alex Howe decide for themselves.”

Three huge artillery barrages took place on the stage, one at night and two during the day. In one 20-second stretch, the special-effects unit set off more than 100 explosions. Ransom enhanced these explosions with Lightning Strikes to give the scene an added sense of horror. “I think we used the 70,000-watt units,” he says. “They generated a tremendous burst of light.” The next day he and his crew moved to the real forest, where the special effects team set off 50 more explosions. Shots from the two locations were then intercut.

According to gaffer Wilson, the biggest exterior lighting setup occurred in Episode 8. Directed by Tony To, who also served as one of the project’s co-executive producers, it concerned the American attack on the town of Haguenau in February 1945. The night of the actual assault was completely overcast, and to create some form of illumination the Army beamed searchlights into the clouds, which then bounced the light back down. “The searchlights gave an overall wash of light,” Wilson says. “That was the actual light source and that’s what we had to simulate.”

Wilson came up with the idea of making a giant soft light, the equivalent of a 100K space light. It had to be able to shed light over a 300-square-foot area on the back lot. Dubbed the “Jimmy Light,” after its designer, the unit was 20' wide by 12' deep and consisted of eight nine-light Maxi-Brutes, all wired to dimmers. “We hung the whole thing on a 200-foot crane, about 120 feet off the ground,” says the gaffer. “The reach of the arm was about 80 feet. It was like an enormous, 20-foot softbox. In addition to the Jimmy Light we had a full Wendy on a cherry picker, as well as a 24K Dino. I think I left them open, neither diffused nor corrected.”

unit was hung

from a crane

arm to provide

this night scene

with an overall

ambience.

Not every episode of the series involves combat or enormous lighting setups. The first episode covers Easy Company’s two-year training at home and introduces viewers to the unusually large cast of characters. “The guys are in training camp, and I wanted to make everything slightly brighter, with more light on their faces, and create a warmer, safer feel,” says Ransom, who shot the episode for director Phil Alden Robinson. “Plus, we had to establish 30 actors in an hour so that the audience could recognize them before they started getting into a dark plane with black shoe polish on their faces!”

That happened soon enough. For the paratroopers’ first nighttime practice jump, there were no lights in the aircraft at all. Ransom underexposed the 5279 three to four stops. “The theory is that you are lighting from the plane’s windows, with the moonlight as the source. We put lights into bounces outside the windows — tungsten light, so we probably put a quarter-to-half-blue on the lamps.” Occasionally, the camera was slung from a kind of mini-rail dolly track, which Williams had built on the ceiling of the C-47, running right down the middle of the aircraft.

A scene of troopers riding a train was shot in an actual boxcar, which was placed in one of the soundstages. “We used a poor-man’s process,” reports Ransom. “We had a greenscreen outside the windows — visual-effects supervisor Angus Bickerton would put in an appropriate background later — and we put lights outside the windows with individual cyclodrums fitted over them. Each cyclodrum had various diffusions added to it, and we’d spin them to help change the density of the light and create the illusion of motion.

“Another trick is that you always want straps or something dangling down as the train moves,” he adds, noting that the grips were actually rocking the boxcar. “When you see something swaying like that, you believe the train really is moving.”

Less amenable to creative solutions was the fog that hung over the backlot during Episode 5, which was directed by Tom Hanks. “Hatfield is a low-lying site and very flat, ideal for an airfield,” notes Adefarasin. “There are many ponds nearby, however, and a huge problem was that at night it got terribly misty, and any sort of backlight lit up the mist. And if you ffontlight in that type of situation, it looks like flash photography.”

The cameraman wound up using Maxi-Brutes and Dinos as backlight while keeping the key as high as he could. Episode 6, which was shot primarily in the forest set, presented a different scenario: fog had to be added. “You light the set and it looks great,” says Adefarasin. “You roll in the smoke and it looks even better. Then when the camera rolls, another lump of smoke springs into frame and either makes the scene too light by raising the fog level, or too dark by filtering the lights! Sometimes it does both at the same time. I was constantly consulting my Minolta spot meter and yelling out two different stops.”

Adefarasin also shot Episode 9, which was directed by Frankel and was an emotional experience for everybody involved. The setting is Germany in the waning days of the war; Nazi soldiers have already fled the area. The men of Easy are walking down a road and come upon a concentration camp. “The concentration camp scenes were all photographed on Vision 200T, without an 85 filter, and then force-developed,” Adefarasin says. “It’s the only footage of mine that we force-developed. However, I didn’t want to introduce more grain, so I went for a very full exposure. The lack of correction lent the images an exaggerated contrast and a bit of color distortion. You knew the men were going into a ghastly area.

“After a few relatively static initial shots, we went for a frenzy of handheld images, circling our troops and the camp survivors. However, we wanted the camera to respect their presence, as if the scene was really happening, so we never got into the actors’ eyelines. For a scene in which Capt. Nixon [Ron Livingston] returns alone to the camp a short time later, we ran the camera at 27 fps. You should barely notice the slow-motion, but I felt it helped give the sequence a haunting feel.”

Adefarasin says Episode 9 was his main motivation for working on the miniseries. “Not a single shot is fired, yet the whole horror of warfare is evident in that hour. [We see] how lives are destroyed, how hate breeds, and the futility of killing our fellow man, but we also see how people help each other. The episode is called ‘Why We Fight,’ and it’s the reason I signed up for Band of Brothers!’

Band of Brothers – Virtual Coloring

The miniseries Band of Brothers was not only shot in England, but all postproduction was done there as well. The 10-part drama was shot on film, and then, in a scenario that is becoming increasingly commonplace, it was digitally color-corrected and manipulated. Going a technological step beyond the recent O Brother, Where Art Thou?, technicians working on Band of Brothers utilized 2K digital data courtesy of Philips’ Specter, a data-storage device that allows “virtual” access to a scanned negative. (See “From Film to Tape,” AC May ’99, for more on the Specter.)

“The Specter is essentially a Spirit without wheels — the electronics of the Spirit but with disks instead of film,” explains Band of Brothers colorist Luke Rainey of Kodak/Cinesite’s new digital-mastering lab in London. “It’s also called a Virtual telecine’ because it has all the functionality of the telecine except it [contains] data rather than film.”

After the episodes of Band of Brothers were edited on the Avid and a cut negative was produced (with 17-frame handles), the negative was scanned at 2K resolution on a Philips Spirit Datacine and the digitized material was loaded into a giant server. For the final coloring and assembly, the filmmakers then utilized the Specter to call up the desired shots and on-line assemble them according to the edit decision list (EDL) provided by the editors. Both the MegaDef grading system and the Pogle control-corrector — which regulates both the Specter and the MegaDef — are products of U.K.-based Pandora International.

“The process of calling up the shots is entirely automated,” says Rainey. “The Specter comprises more than 3,000 gigabytes of hard disks to store the 1920x1440 images, a control system which enables us to play these images in real time, a basic edit system that automatically assembles the shots in the order dictated by the EDL, and a very comprehensive grading and reframing system.”

Visual-effects shots were also loaded into the Specter as they became available and were matched to their previously timed background plates. Opticals — such as wire removal, speed changes, adding camera shake, etc. — were then pulled into the Specter. When everything was finished, the episode was output to EID-D5 tape. From there, it could be played out in a wide variety of delivery formats and aspect ratios.

“I wanted to keep the skin tones more natural than other parts of the picture, so I [often] isolated skin tones and desaturated the

remainder of the picture.”

— colorist Luke Rainey

“The most important thing on this show was to keep the viewer close to the characters,” Rainey notes. “For this reason, I wanted to keep the skin tones more natural than other parts of the picture. Because I can select any entity within a frame and manipulate it separately from the rest of the picture, I would isolate the skin tones and desaturate the remainder of the picture. If there is any other color or object that should be noticed — such as the mailbox in the battle scene of Episode 4 — I’d bring that back as well.”

Cinematographer Remi Adefarasin, BSC, who alternated shooting episodes with Joel Ransom, CSC, was concerned about how green leaves and fields would photograph at night. “In the spring, the trees and grass are lush and light, and when backlit they look like a cartoon,” Adefarasin observes. To solve the problem, Rainey significantly reduced the color green throughout the series and timed down highlights in foliage in night scenes.

“Greens tend to overpower the pictures,” agrees the colorist. “Of course, when you take color out, you lose apparent contrast, so I some¬ times used the greens in a slightly distorted manner, bending them toward another color, making them more ochre or olive, and thus put a wash behind the foreground characters, who were wearing uniforms pretty much the same color as the background. I then flared out the skies to create a layered effect.”

Electronic “grad filters” (typically called Power Windows, which is the name they’re given in da Vinci color-correctors) were used extensively throughout the timing process. These work in the same way that a conventional grad does; however, instead of applying a color effect across the whole frame, it can be feathered in from an edge or even placed over an object and tracked. Rainey sometimes did this to reduce highlights on the side of a face. In wintry episodes, the filter effect allowed him to flare the snow without affecting the trees.

The data aspect of the process is the key that enables Rainey to do the things he does. He adds that when dealing with video in the past, he was always limited by color depth (i.e., the palette of colors available). But by working with virtual 2K data, he can be much more precise in composing the color imagery of a shot. He notes that “every shot in all 10 episodes contains at least four layers of color effects, and often as many as eight. Blacks are squeezed, whites are flared, skin tones are manipulated and grads are added.” — Jean Oppenheimer

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.