Crafting Legacy for House of the Dragon

ASC member Fabian Wagner, director-showrunner Miguel Sapochnik and a trio of alternating cinematographers discuss the new looks they helped create for the HBO prequel series.

During its eight-season run, Game of Thrones became the most-watched show in HBO history and the most Emmy-decorated narrative series ever to air.

While regaining that viewership and critical prestige for its new prequel, House of the Dragon, is certainly a priority for the network, veteran Game of Thrones cinematographer Fabian Wagner, ASC, BSC felt that replicating the look of the original series wouldn’t be the proper path.

“I’ve got to be honest — I was a little reluctant in the very beginning because I didn’t want to repeat myself,” says Wagner, who photographed three episodes of House of the Dragon, including the pilot. “I wanted to make this new show as distinct as possible.”

A New View of Westeros

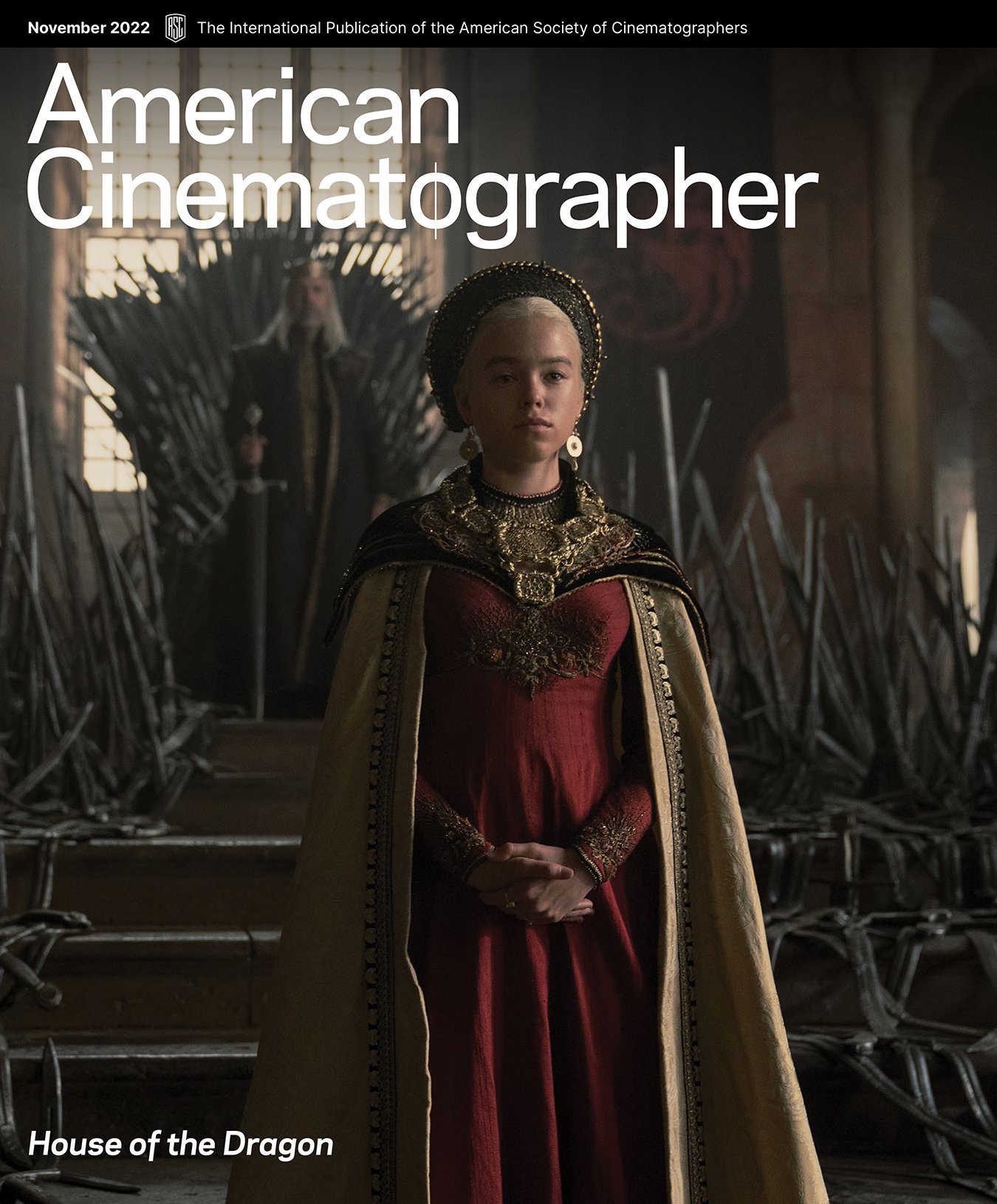

Set 200 years before the events of Game of Thrones (AC May ’12 and July ’19), during a time of relative peace and prosperity, House of the Dragon finds Westeros ruled by King Viserys (Paddy Considine) of House Targaryen. The show’s central conflict revolves around who shall succeed Viserys on the Iron Throne, with potential heirs including the king’s eldest daughter, Rhaenyra (Milly Alcock in adolescence and Emma D’Arcy in adulthood), and his brother, Daemon (Matt Smith).

Much like its predecessor, the new series offers an absorbing concoction of palace intrigue, gore-soaked battles and skies alight with fire-breathing beasts. But unlike Game of Thrones, House of the Dragon incorporates a different camera and lens package, a wider aspect ratio, a new show LUT, an HDR-centric grade, and virtual-production work.

The show reunites Wagner with Miguel Sapochnik, who directed six of the eight Game of Thrones episodes filmed by the German-born cinematographer, including “Battle of the Bastards” (from Season 6) and “The Long Night” (Season 8).

Sapochnik — who served as executive producer and co-showrunner on House of the Dragon in addition to his directing duties — notes that when he first met Wagner, he recognized “a deftness in the way he lit things, which was very much about lighting spaces and not faces.” He adds that “the idea of doing this new show without him would’ve filled me with dread.”

Fire, Blood and Glass

House of the Dragon is adapted from George R.R. Martin’s 2018 novel Fire & Blood — about the Targaryen’s family history — whose title inspired the names of the show’s simultaneous shooting units. Unlike a typical block-shooting approach, whereby one cinematographer completes a “block” of episodes before handing off the crew to the next, House of the Dragon used a “cross-blocking” schedule, in which multiple cinematographers worked simultaneously. So, while Wagner might have been toiling with the Blood Unit on the Iron Throne set at Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden for a scene in Episode 1, another of the show’s cinematographers — among them, Pepe Avila del Pino, AMC; Alejandro Martinez; and Catherine Goldschmidt — might have been working on a backlot set with the Fire Unit for a different episode.

“We have these amazing, gigantic sets, which are an absolute joy to light. I suggested to Miguel early on that we should look at shooting large format on the Alexa 65 to really capture the feel of them.”

Whereas Game of Thrones was shot mostly on various Super 35-sized Arri Alexa sensors paired with Cooke and Angénieux lenses, the Blood and Fire Units on House of the Dragon were outfitted with Arri Rental Alexa 65s for A-cam and Arri Alexa Mini LFs as additional cameras. “We have these amazing, gigantic sets, which are an absolute joy to light,” says Wagner. “I suggested to Miguel early on that we should look at shooting large format on the Alexa 65 to really capture the feel of them.”

For lenses, Wagner chose the Arri Rental Prime DNAs and DNA LFs, along with Fujifilm/Fujinon Premista zooms (28-100mm T2.9 and 80-250mm T2.9-3.5). Canon 200mm and Nikon 300mm long primes rounded out the set. Wagner says he tended to live around a T4 — partly to emphasize the fine detail of the production design, and partly to give his focus pullers a fighting chance. He also favored the wider end of his lens set, frequently leaning on the 28mm and the 35mm. However, he developed a particular affection for the Prime DNA 58mm, one of three “T Type” lenses in the package — with distinct focus falloff around the edges of the frame.

New Rules / No Rules

Because Game of Thrones’ story extended to the far reaches of Westeros, the show employed a vast library of LUTs to distinguish the different locations. However, for the King’s Landing-centered House of the Dragon, Wagner opted for a single show LUT. One of the primary features of that LUT — created by DIT Ian Marrs and colorist Asa Shoul — was pushing the exposure down a stop so the cinematographers could indulge in the show’s penchant for darkness, while still retaining information in the digital negative.

“I call it an ‘under LUT,’” Wagner says. “It’s a LUT that shows the image one stop darker, so you still expose the image correctly and have room to play.

“Game of Thrones was a very high-contrast show, and this has a much softer curve,” he continues, adding with a laugh, “but there’s still a lot of shadow, which was something Game of Thrones was always famous — or sometimes infamous — for.”

The inclusion of Marrs — a frequent collaborator of Wagner’s — on the crew also offered an added benefit for the cinematographer. “I love operating,” Wagner says, “and when we had three or more cameras, I would always jump on one because I could totally rely on Ian to make sure everything was the way that we’d talked about. We’ve worked together for a very long time, and I trust him 100 percent.”

Wagner’s trust extended to his fellow House of the Dragon cinematographers. Says Martinez, who shot Episodes 4, 5 and 9 for director Clare Kilner: “The first thing that Fabian told us was, ‘You can do whatever you want. I’m not going to give you any rules.’ If we wanted to change the lights or even change the whole mood, we were able to. It was an amazing way to work.” He adds that Wagner “was an amazing collaborator and an inspiration for all of us.

Goldschmidt, who shot Episode 8 with director Geeta Vasant Patel — and was named one of AC’s Rising Stars of Cinematography earlier this year (AC Aug. ’22) — notes that her late entry on the production forced her to approach coverage in especially unique ways. “Some of the sets had already been shot to the nth degree,” she says. “So, we thought, ‘Where can we put the camera that people haven’t put it before?’ For example, the art department was more than happy to fly out a wall that had never moved before, so that we could put the camera there. Everybody on the show wanted us to put our stamp on what we were doing, and wanted to help us do that.”

She adds that the series’ cross-blocking schedule led to an unusually long production period for her — seven months for a single episode. “Sometimes, we would only shoot one day a week, but it was great to be able to have that time with the sets and with Geeta,” she says.

Another Wagner proclamation: “There’s no such thing as too dark.” Del Pino, who shot Episodes 2, 3 and 10, wasted little time testing that statement. “On my first day, we did a whole scene that I lit only with one practical torch,” he says. “No lights. The whole G&E team was getting anxious because they had nothing to do.”

Goldschmidt also pushed the boundaries of darkness — and found them. “We tried a few things on our first day of shooting and we were told to pull back a little,” she says. “Turns out there was such a thing as too dark!”

Widening World

One boundary Wagner was happy to be free from was the original series’ 1.78:1 aspect ratio. Wagner and Sapochnik hoped to expand all the way to 2.4:1, but HBO balked at going full widescreen. The cinematographer and showrunner didn’t give up easily, going as far as setting up 2.4:1 frame lines and framing their early scenes to protect for that ratio in case the network later relented.

“We fought very hard, but at some point we realized it was a losing battle,” says Sapochnik. “However, I don’t think [the instinct to compose for the wider frame] ever really left us.” House of the Dragon ultimately settled in at 2:1. “It’s such a cinematic show with such an incredible scale that it just lends itself to widescreen,” says Wagner. “Every single set and shot benefitted from that wider frame.”

Lighting the Throne

While location work on the series was done in Portugal and Spain, most of the show’s cavernous sets were constructed at Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden — near London — where production commandeered seven stages. That included a stage to create this series’ version of the Iron Throne set. The throne itself is quite similar to the one depicted on Game of Thrones, but scores of fused and warped swords that surround it are new to the audience.

“I remember going into that set for the first time on Season 4 of Game of Thrones and thinking, ‘I don’t have a clue how to light this,’” says Wagner. “The key for me on House of the Dragon was lighting that space in a way that created flexibility. I shot four scenes there, and I wanted to create four very different lighting scenarios that I could move between as quickly and efficiently as possible.

To create that flexibility, Wagner used three soft boxes filled with Arri SkyPanel S60s — one over the throne itself, one in the middle of the room and one toward the entrance. Shooting through the room’s tall, thin windows were Luxor Lights from Light Synthesis — which Wagner refers to as “LED Wendys” — and 24Ks; the former were bounced into Full Silk to give a soft throw of light, and the latter were employed when hard light was desired.

A candle-laden chandelier was rigged overhead with gas flames, and smaller sources dotted the room to illuminate specific areas. To create shafts of light, 10K Molebeams were blasted through haze pumped onto the set. Greenscreen was placed outside the throne-room windows when necessary — but Wagner favored either blowing out the windows for daytime scenes by overexposing the white background outside, or darkening them for night by placing black material over the white.

This marked the first time Wagner had used Luxor Lights, and he quickly became enamored with them. “The throw and the quality of the light is amazing. I also liked them for practical reasons. We were shooting through the summer, and it would have been incredibly hot in those sets if we used actual Wendys or purely tungsten lights.

Del Pino was equally impressed with the fixtures. “The rigging gaffer showed me these super punchy LED lights that were round and about 2 feet in diameter,” he says. “I started using them on almost every set. I would make a row of eight or nine of them and put a little bit of thin diffusion in front so it would basically become a 12'x2' source. I liked to put them above windows, just out of frame.”

Martinez’s time in the throne room included a 25-page night wedding scene in Episode 5, which he personalized with a brigade of tungsten Source Four Lekos. Says Martinez, “Set dec had these long, beautiful tables with candles on them, so we decided to point [roughly] 100 Lekos straight down from the top of the studio to bounce off the tables.

Virtual Assist

In the world of House of the Dragon, only three sources of light exist: firelight, moonlight and daylight. When shooting exteriors around Leavesden, that daylight was often unreliable — though Wagner says the English weather was an improvement over Game of Thrones’ Irish base of operations. “In London, there’s no consistency to the weather, but Northern Ireland was definitely more unforgiving,” he recalls. “In Ireland, you could literally have four seasons in one day, which is what I experienced on ‘Battle of the Bastards.’” That said, England’s notoriously overcast weather wasn’t a problem on Leavesden’s V Stage, a new virtual-production facility with upwards of 2,600 LED panels offering up faux sunlight on demand. House of the Dragon was the first show to use the new 7,100-square-foot wraparound virtual production environment.

Wagner’s time on the V Stage included an extended sequence set on the bridge to Dragonstone, the ancestral seat of House Targaryen. A practical location in Northern Spain was used for the bridge on Game of Thrones, but a virtual set proved more feasible, considering the 20-odd characters — and flying dragons — required for an Episode 2 standoff.

The V Stage was also used extensively for dragon-riding sequences. When filming these scenes, Wagner opted for a hybrid approach: For wide shots, the LED panels were turned blue, essentially morphing the space into a bluescreen stage. For close-ups, sky backgrounds were placed on the LED panels as in-camera composites.

For an extensive dragon-fight sequence in Episode 10 — shot by del Pino — storyboards, animatics and sophisticated previs sequences were created. But first, the original Top Gun and a pair of Harry Potter dragons served as inspiration. “We worked on that sequence for a year. I started putting together an edit with airplane sequences from Top Gun and from other dragon films, just to have a sense of what camera movements we would like to use,” del Pino says. “From there, director Greg Yaitanes and I choreographed the sequence with toy dragons from Harry Potter — just holding them with our hands and shooting it with an iPhone. We were basically playing like little kids. That was really fun.”

To supplement the interactive lighting provided by the V Stage’s LED panels, del Pino rimmed the top of the stage with SkyPanel S60s. Shooting desk operator Danny Cunningham also took over control of the LED panel luminance to expedite lighting changes. “We had a very steep learning curve, but we got to a point where the workflow was five times faster than when we started,” says del Pino, who spent roughly 30 days on the V Stage.

Wagner had his own virtual production learning curve as well. “I started off using much more film light — and then, gradually, I learned to embrace this new aspect of filmmaking and began using the volume itself to light,” he says. “I can’t say I liked [shooting on the V Stage] initially, but I did eventually start to enjoy it. I’m quite excited about spending more time in there and pushing things even further.”

Spotlight on Color | Hues, Grain, HDR

When colorist Asa Shoul presented his first pass of the House of the Dragon pilot to Miguel Sapochnik, the showrunner replied, “It looks a bit too Game of Thrones.” Having just finished a five-week preparatory binge of the entire series, Shoul understood the note.

“This is not a criticism of the original show — which I thought was graded beautifully — but I think Miguel felt the last couple of seasons had gotten more contrasty, and the shadow detail had gotten crushed a bit,” says Shoul. “For House of the Dragon, we talked about seeing that detail, because the costumes and the sets are very rich and it’s a more colorful world they live in than Game of Thrones. For me, it was like the 1920s — an age of wealth, prosperity and enjoyment.”

In Game of Thrones, King’s Landing took on a golden hue to contrast the city to the cool Northern environs of Winterfell. With House of the Dragon largely unfolding in the former locale, that visual counterpoint became unnecessary. “We went with a more neutral look, while letting colors come through as long as they weren’t too bright and gaudy,” Shoul says.

“For example,” he adds, “each character’s costume colors often represented their house. Queen Alicent (Emily Carey) wears green to the wedding in Episode 5 to show her allegiance — and [Alicent’s family] the Hightowers are referred to in later episodes as “the Greens.” Also, each dragon has a specific color, so that they are more easily identifiable in flying duels. The neutral grade meant that, where possible, we didn’t apply a color wash or tint to scenes.”

To add a touch of the imperfect to the pristine Alexa 65 and Mini LF images, Shoul used a LiveGrain selection based on Kodak Vision3 500T 5219. “The LiveGrain gave it a more filmic look, and I also added diffusion across the board just to break up anything that felt too digital or sharp,” he notes. “I used other softening tools as well, at times on close-ups — with fine face or hair detail, or with dragons that looked too sharp.”

Working in Baselight, Shoul graded on Sony BVM-X300 monitors. Unlike Game of Thrones, the HDR version became the primary deliverable. “It’s much easier to get the HDR version right and then go down to SDR than the other way around,” says Shoul. “The HDR is going to be the one that lives forever. That’s the one that everyone sees on their newer TVs and iPads.” He adds that the season was graded in HDR at 1,000 nits in Rec 2020 color.

Before beginning work, Shoul created a new LUT as a starting point, tweaking the show LUT used on-set to account for elements that were imperceptible on production’s SDR monitors. “What no one realized on-set was that the LUT was making highlights very gold or pink. The skies were going a bit of a crazy color, which you could only see in HDR.”

It’s an example of why Shoul hopes to see the adoption of HDR monitoring throughout the entire production workflow. “If we’re finishing in HDR, we should be monitoring in HDR. Sometimes, VFX will come down and see their work in HDR for the first time, and they’ll see skies or flames be different colors, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, it didn’t look like that on our monitors.’”

Shoul compares the shift in dynamic range to the transition in audio technology from mono to 5.1 surround sound. “HDR gives you these new tools, but just because you can now put a dog barking in the background on one of the tracks doesn’t mean it’s not going to be distracting. It’s the same with HDR. If it’s used incorrectly, it can look gimmicky and distracting. What we try to do is use it to make the viewing experience more immersive.”

— Matt Mulcahey