Dark Deeds Abound in Tower of London

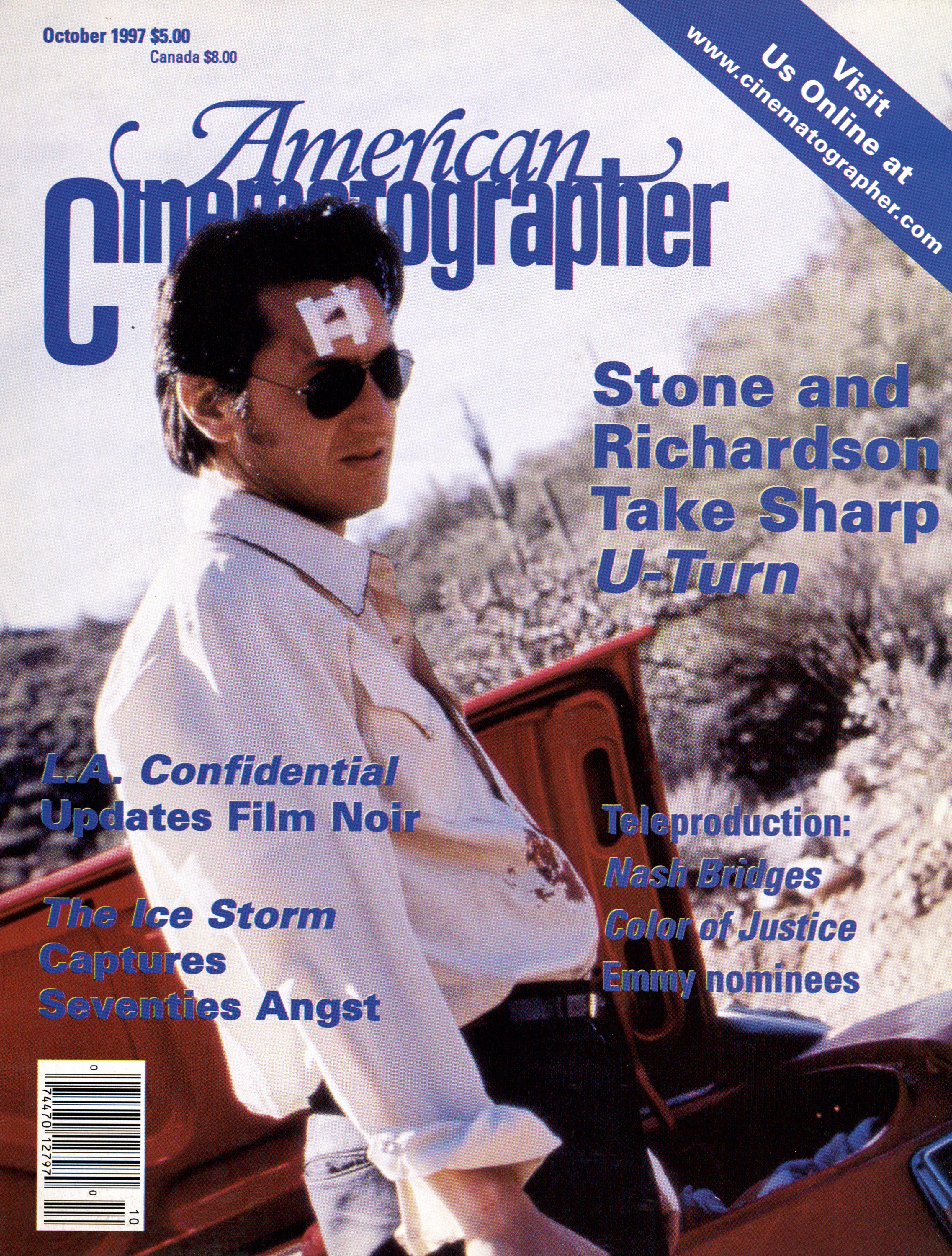

Sumptuous spectacle was the order of the day in Universal's 1939 retelling of the Richard III legend.

No age is without its ruthless men who, in their search for power, leave dark stains upon the pages of history," we are told in the prologue to Universal's memorable 1939 movie Tower of London. "During the Middle Ages, to seize the Tower of London was to seize the throne of England. Within the deep shadows of the Tower walls live the population of a small city, some in prison cells and torture chambers, some in palaces and spacious lodgings, but none in peace. A web of intrigue veils the lives of all who know only too well that today's friends might be tomorrow's enemies"

The most ruthless man of all, according to the film and many historians, was Richard Plantagenet, duke of Gloucester, destined to become King Richard III. In Tower, the infamous plotter is superbly portrayed by Basil Rathbone, then at the peak of his career. He is abetted by Boris Karloff, the reigning king of horror films, as the equally twisted Mord. A more fiendish teaming can hardly be imagined.

Much of Richard's infamy is founded upon William Shakespeare's plays Henry VI and The Life and Death of King Richard III, in which the scheming, hunchbacked politician murders his way to the throne. His victims include the elderly King Henry VI, the Duke of Clarence (his own brother), and a pair of boy princes. Shakespeare depicted Richard as a cruelly deformed monomaniac, self-described as having an arm "like a wither'd shrub an envious mountain on my back legs of an unequal size disproportion in every part, like to a chaos, or an unlick'd bear-whelp"

Many revisionist historians insist, however, that Richard was a just ruler who became a victim of slander after he was slain by the army of his successor, Henry Tudor. Even after workmen repairing a stairway found the skeletons of the missing princes, it was suggested that they were killed by the Tudors. As for alleged deformities, Richard's official portrait reveals a pleasant-looking man, although his right shoulder does appear to be higher than his left. But then, was there ever a royal artist with the chutzpah to paint an unflattering portrait of his king? [The remains of Richard III were discovered in 2012, and do seem to confirm the deformities]

Tower of London was shepherded by producer-director Rowland V. Lee and his screenwriter brother, Robert N. After penning 1922's Shirley of the Circus for Fox Film, the pair had worked together on several other productions. Their collaborations were contentious. "We write it out and fight it out," Robert Lee explained. "That's the advantage of being brothers. We can say things to each other that nobody else would take." They liked on-set improvisation, and Robert stood by during production to make changes.

In 1936, following Rowland's successful historical dramas, The Count of Monte Cristo and Cardinal Richelieu, the brothers decided to write an English history yarn. Robert immersed himself in reference books, while Rowland went to England to do some research at the British Museum. "We agreed that we wanted to use the roughest, [most] hard-boiled period of all time," Robert said in a press release. "Row was for the Stuart era. It was tough, all right, but I held out for the time of Richard. Those guys made our moderns look like sissies We found by examining the old armor that they were little guys, but they were game. They didn't squeal the way our big-time gangsters do when they had to pay up. The only record of a gallows welcher in history is that of Margaret of Salisbury. She tried to run and they cut her down. But Marge was 71 years old. When I proved all of this, Row agreed with me."

Rowland Lee directed what has been called the most beautiful of all talking pictures, Zoo in Budapest (1933), photographed by Lee Garmes, ASC. He also had a penchant for the macabre, as demonstrated in his two popular Fu Manchu chillers of 1929-30. While in England, he directed Ann Harding and Basil Rathbone in the hair-raising Love From a Stranger (1937), and was impressed with Rathbone's projection of suave villainy. At Universal the following year, he directed Rathbone, Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi and Lionel Atwill in the expensive but worthy Son of Frankenstein, sparking the rebirth of the neglected horror genre. He and Rathbone then collaborated on The Sun Never Sets (1939), a stiff-upper-lip tribute to the British Empire which Lee jazzed up by casting Lionel Atwill as a mad scientist to the outrage of critics and the delight of shirtsleeve audiences.

In the wake of these projects, Universal gave the Lees the go-ahead for Tower of London, granting the duo one of the largest budgets they had offered in years: $500,000, with a 36-day shooting schedule. A great amount was allotted for the construction of a replica of the real tower, and another large chunk went to costumes for 75 feature players and some 300 extras. The cast was an expensive one; Rathbone and Karloff, for example, were in the $5,000-per-week class. Obviously, such a picture could not be finished in six weeks.

The real tower stands on the north bank of the Thames in London's East End, and is maintained as a tourist attraction. It is a collection of thick-walled stone buildings covering 13 acres and centering around the huge White Tower, built by William the Conqueror as a palace and prison. A high stone wall and moat surround the spread. Many famed historical personages were imprisoned and beheaded within the walls or on an adjacent hill. The crown jewels are housed on the premises, and the Beefeaters (or Yeomen Warders) still stand guard in their traditional garb.

Until quite recently, Universal's tower also stood intact; the structure appeared in dozens of movies for more than five decades and was a vital feature of the studio's tour. During preparation for Tower of London, supervising art director Jack Otterson, an architect who had designed part of the Empire State Building, was assigned to create a reasonable facsimile of the historic edifice, which would then be constructed on the backlot. He and unit art director Richard Riedel made 75 charcoal drawings and watercolor paintings mainly accurate reproductions of the exteriors, including the portcullis and the 90' keep tower, and interiors such as the royal chambers, torture chamber, prison cells, chapel, council rooms and bedrooms. Riedel saw the project through to completion. Exteriors were scaled down somewhat (the keep, for example, was reduced to 75'), and certain elevations were left uncompleted (to be finished with matte paintings by Jack Cosgrove, ASC and Russell Lawson, ASC). The sets were massive, imaginative and planned for staging in depth.

It became evident that there was little opportunity to economize on the project. Some necessary props were already in inventory, such as torture instruments, hand-carved cabinets, and oversize furnishings from the 1923 Hunchback of Notre Dame. Mord's iron maiden had previously been used to dispatch Conrad Veidt in 1927's The Man Who Laughs.

Principal photography began on August 11 with virtually the same crew that had collaborated on Son of Frankenstein, including the Otterson-Riedel team and cinematographer George Robinson, ASC. Robinson's gift for creating strong radial compositions and dramatic shadow-play was again a critical factor. Lee and Robinson deliberately avoided the sweeping crane shots deemed necessary for most spectacular productions, opting instead for a minimum of camera movement.

RKO had wanted Rathbone to play the principal villain's role in their even bigger historical horror show, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939), but he was already committed to Rio and Tower. In fact, he was also completing Rio during his first week's work on Tower.

Actors portraying Richard have varied his appearance and personality considerably. In early screen versions, stage stars Sir Frank Benson (1911) a cousin of Rathbone and Frederick Warde (1912) scuttled about, exploiting the character's misshapen body to the fullest. John Barrymore, in his famed Broadway version as well as a marvelous soliloquy filmed in 1930 for Warner Bros.' The Show of Shows, wore a huge hump on his back, but moved gracefully and presented an almost heroic monster. In the 1955 Richard III, Sir Laurence Olivier performed the character as a soft-spoken sneak with elongated nose, large hump, withered arm and deformed hand. In the 1995 version, Sir Ian MacKellen updated the black-hearted monarch as a Nazi.

Rathbone's Richard is a hearty man of action, a great swordsman hardly burdened by his hunched left shoulder. Behind a secret panel he keeps a small diorama of the throne room, with mannequins of the current monarch attended by the six in line of succession. Richard is last. When an heir is eliminated, whether through Richard's machinations or by attrition, Richard tosses the decedent's effigy into the fireplace and moves the others a step closer to the throne. His ambitions are shared only with his worshipful acolyte, Mord, executioner and constable of the tower, who tells him: "You're more than a duke to me, more than a king. You're like a god to me."

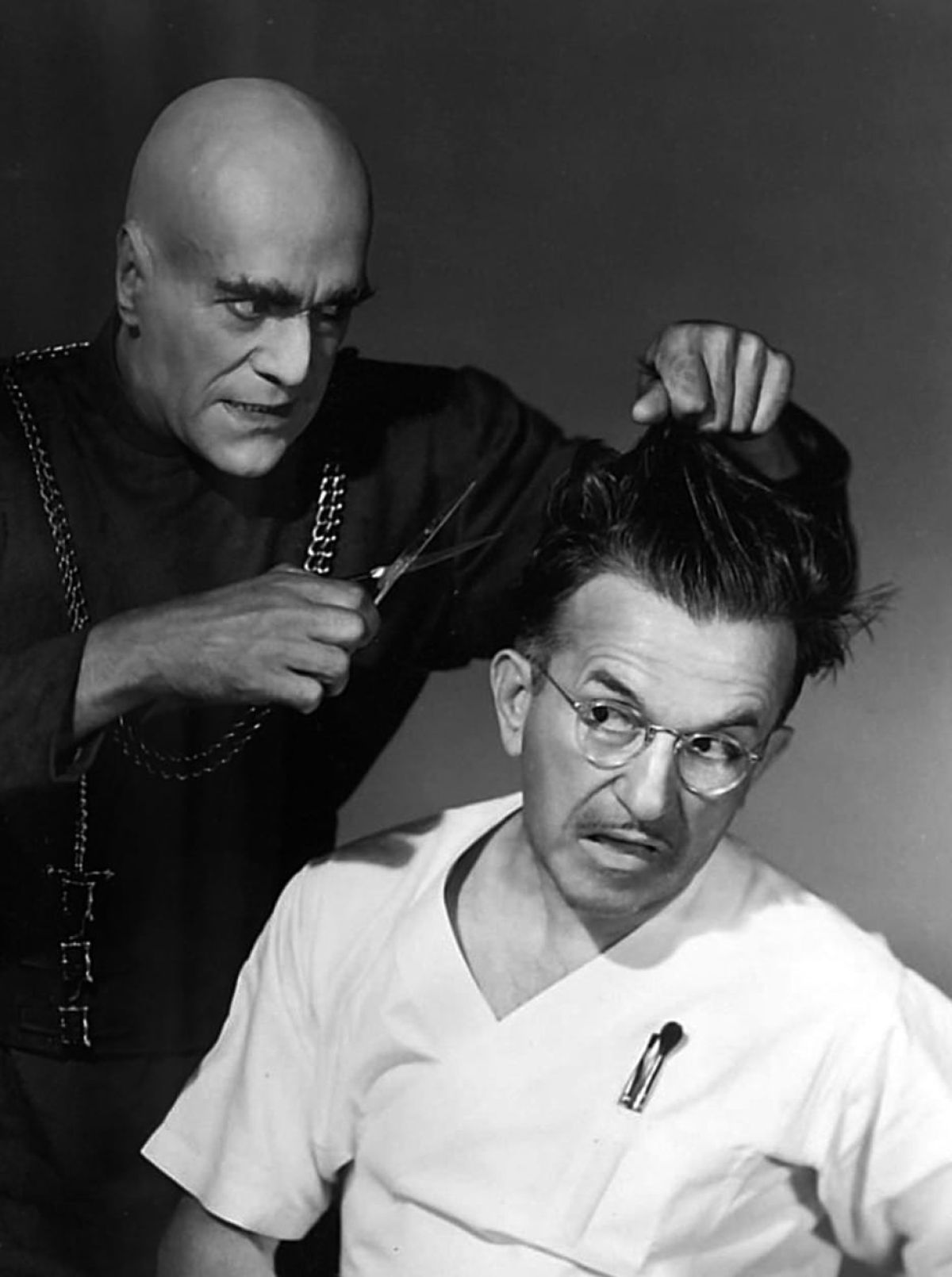

Mord is the only wholly fictitious major character in the movie. Jack Pierce, creator of Karloff's makeup for Frankenstein, The Mummy, The Old Dark House and other classic Universal chillers, manufactured Mord's grim visage. With a shaved head, hawklike nose, flattened ears, huge shoulders, a twisted leg and a clubfoot, along with Karloff's inexplicable ability to seem larger than everyone else, Mord is an admirably terrifying heavy.

Tower of London closely resembles the Shakespeare version of Richard's tale, but is less complicated and offers updated easier-to-follow dialogue. The story spans the years 1471-1485, opening before the Battle of Tewkesbury and closing after the Battle of Bosworth. King Edward IV (Ian Hunter) has usurped the throne and imprisoned feeble-minded King Henry VI (Miles Mander). When Edward orders the execution of Lord DeVere (John Rodion), John Wyatt (John Sutton) gets the permission of his cousin, Queen Elysabeth (Barbara O'Neil), to stand by the martyr on the gallows. This incurs the displeasure of Edward and his youngest brother, Richard of Gloucester. For political reasons, Edward orders Wyatt to marry an elderly dowager. Wyatt, who loves Lady Alice Barton (Nan Grey), the Queen's lady-in-waiting, refuses and is imprisoned in the tower.

When Henry's son, the Prince of Wales (G.P. Huntley), leads an invasion against the throne, Edward and Richard take Henry into battle, hoping he'll be killed. Richard, in love with Wales's wife, Anne Neville (Rose Hobart), kills his rival at Tewkesbury. Henry returns unscathed. George, Duke of Clarence (Vincent Price), Richard's older brother and husband of Anne's sister, Isobel (Frances Robinson), hides Anne. If Richard marries Anne, Clarence will be forced to divide the Neville estate.

Richard has Mord murder old Henry. Mord's spies find Anne, and she is tricked into marrying Richard. Following an argument, Richard challenges Clarence. Knowing Richard's prowess in combat, Clarence, a heavy drinker, chooses wine as his weapon. Richard loses the duel, but he and Mord drown Clarence in a butt of malmsey.

Six years later, after freeing Wyatt, Edward dies. His elder son, the young Prince Edward (Ronald Sinclair), becomes king, and Richard is made his protector. Fearing Richard, Elysabeth has Wyatt steal the king's treasure to help the exiled Henry Tudor (Ralph Forbes) against Richard. At Richard's command, Mord's men murder the boy king and his younger brother, Prince Richard (John Herbert-Bond). Wyatt is captured and tortured, but Alice, disguised as helper to chimneysweep Tom Clink (Ernest Cossart), helps him escape. Tudor marches on London. During the battle of Bosworth, Richard is killed by Tudor, and Mord dies by Wyatt's sword.

the royal treasure. Mord officiates with the aid of Bunch (Donald Stuart).

Ian Hunter, a burly South African, offers a brutal but high-spirited portrayal of King Edward, whose philosophy is "Marry your enemies and behead your friends." The queen is played by Barbara O'Neil, the dignified actress who portrayed Scarlett's mother in Gone with the Wind. Vincent Price, recently arrived in Hollywood after his stage successes in London and New York opposite Helen Hayes in Victoria Regina, is splendid as the cowardly, blubbering Clarence. Nan Grey, a lovely blonde from Texas, is a pleasing romantic lead even though she lacks an English accent. John Sutton, an India-born graduate of Sandhurst, former African white hunter and Far East tea plantation manager, is a natural for the heroic Wyatt.

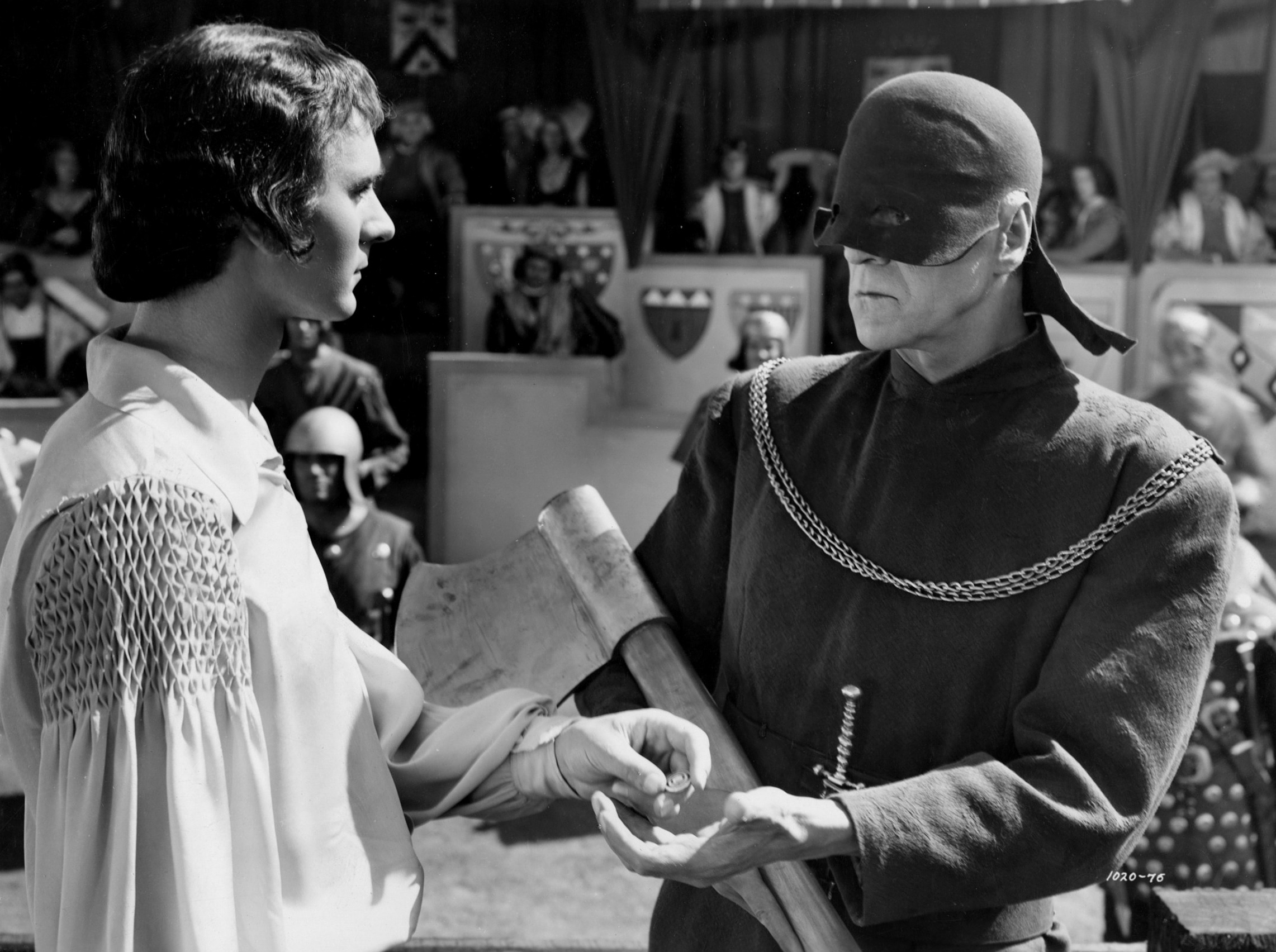

Ernest Cossart provides good comic relief as Tom Clink. Rose Hobart is lovely and sympathetic as the deluded Anne, a role severely shortened in the final cut. One of Mord's well-chosen henchmen is Al Brady, who also appeared in Warde's 1912 Richard III. John Rodion, impressive as the first victim of Mord's axe, was actually Rodion Rathbone, son of Basil. There's a nice moment when he is about to say his last words and the sheriff (Reginald Barlow) whispers, "Make it short, I pray you, so as not to tire the King." DeVere also tips Mord for his services: "Here is a groat, the smallest coin I know."

Miles Mander, fine as always, is the feeble King Henry, who is at prayer when Richard hands Mord his knife, saying, "It is an occasion for a blade in the shape of a cross. It will ensure the thrust and bless the wound." Henry's prayer is cut short and Richard finishes for him.

The drinking duel between Richard and Clarence is beautifully played. According to Vincent Price, Lee let the actors ad-lib much of the sequence, and filmed it in one day. In the wine cellar, the adversaries down large mugs drawn from a butt of malmsey. Richard becomes increasingly surly as the contest progresses, while Clarence becomes almost hysterical with laughter. Eventually, Richard passes out and Clarence crows his triumph. Richard revives, however, and slams Clarence to the floor. Mord emerges, and the evil allies dump Clarence into the vat. When Clarence comes up for air, they push him under and slam the lid. Listening to the man's dying bubbles, Richard mutters, "He asked for malmsey."

Price still had vivid recollections of the sequence some 30 years after the fact. "They used watered-down cola for the wine, and Basil and I had to drink quarts of it and slosh around in it," he remembered. "I can't stand the stuff to this day. Like a fool, I volunteered to do the drowning scene myself rather than be doubled. Basil and Boris were kidding me beforehand and took great delight in throwing their cigarette butts and other trash into the vat. The stunt coordinator told me that when they dumped me into the vat and slammed the lid down I was supposed to grab hold of a bar at the bottom and count to ten before coming up. After I did all that the lid was still closed! Then I heard the crew breaking in with axes. Boris had sat on it and Basil leaned on it and it got stuck. They managed to pull me out before I drowned."

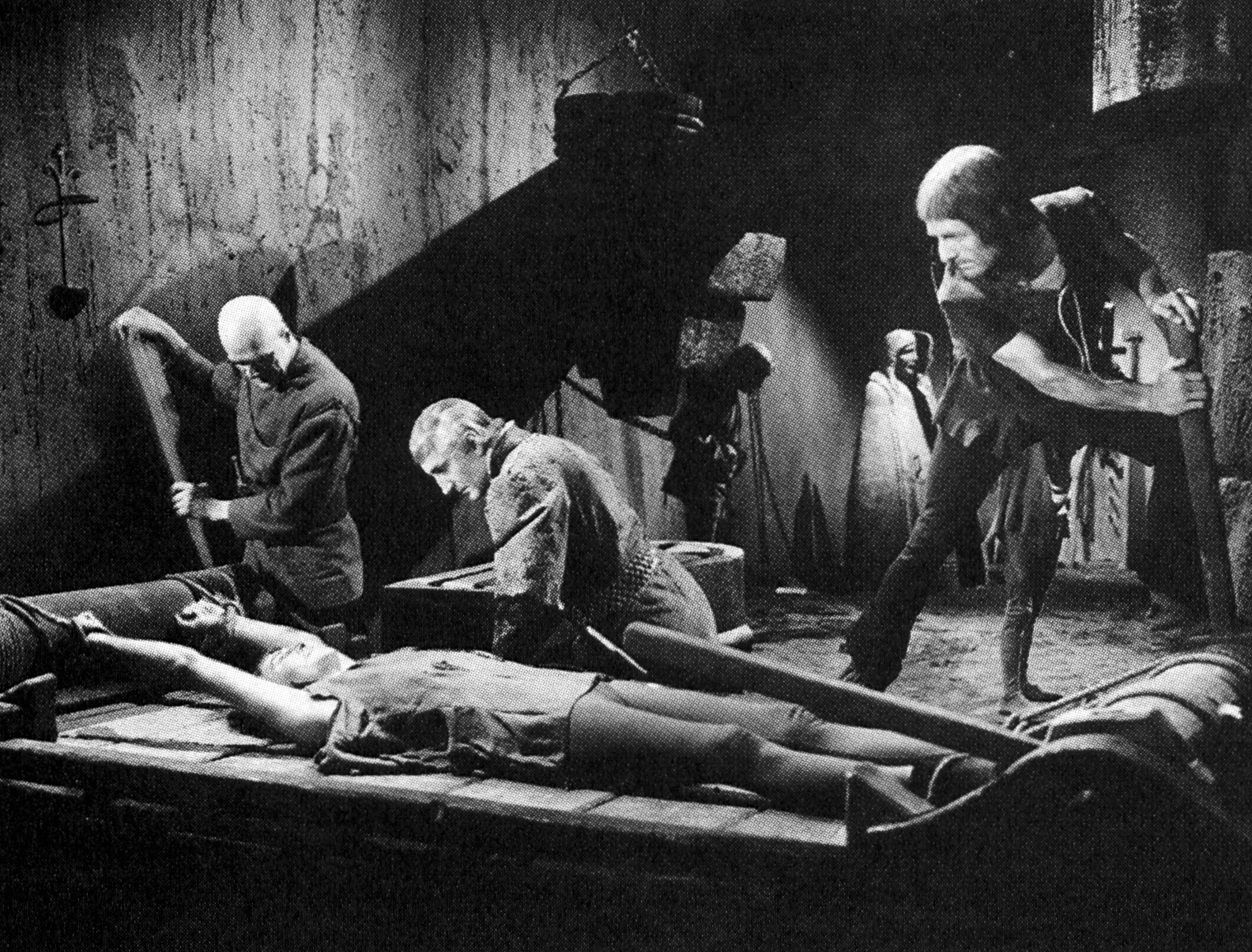

The murder of the children, which upset many patrons, is less graphic than in some earlier versions of the tale. After the king goes to bed, the little Prince falls asleep while kneeling at prayer. Mord, horrified at what he must do, picks up the Prince tenderly and then tucks him into bed. He measures the older boy's height with his hands and goes outside to show his three assassins the proper size of the graves they must dig. Returning with the men, he is reluctant to carry out his orders, but suddenly regains his composure and pushes his minions forward.

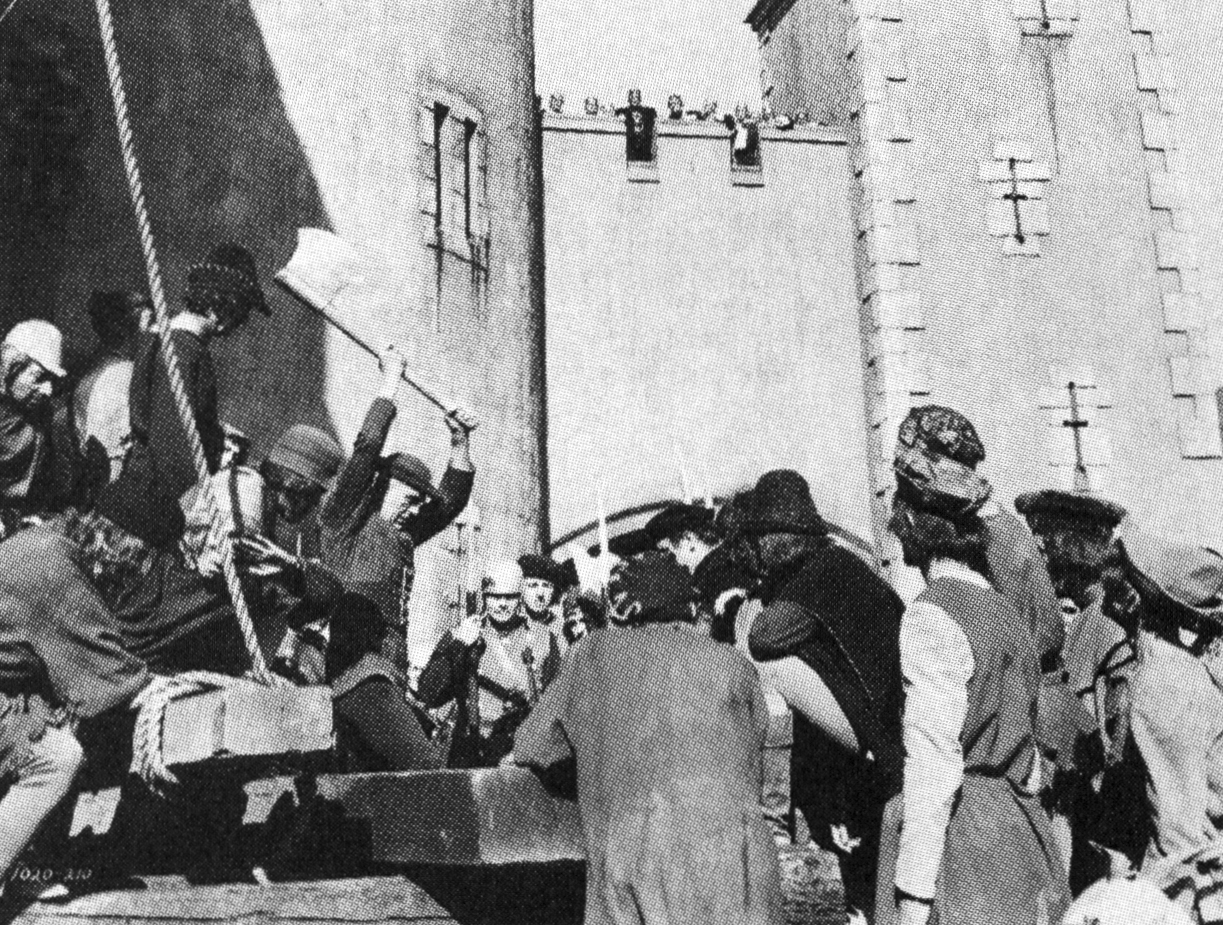

Great difficulties were involved in the staging of the battles of Tewkesbury and Bosworth, which were filmed in August during a record heat wave that claimed several lives in Southern California. The censorship office warned the studio not to show much bloodshed in the battle scenes and suggested that the filmmakers cover up the details by printing the scenes dark. Lee decided to film Tewkesbury in rain and Bosworth in fog, which would satisfy the censor's demands while yielding more picturesque visuals.

At 4 a.m. on August 19, principals, crew members, stuntmen and 300 costumed extras reported to a ranch at Tarzana, about 20 miles north of the studio. The early call was necessary to get the combatants and cameras in place on the uneven terrain, and to enable the special effects men to set up a battery of fog machines before the heat of day. Outdoor fog effects can be dicey due to the vagaries of wind, temperature and atmospheric conditions. Continuous gusts of wind shredded the fog. Only a few shots were attempted before Lee ordered the rain machines to be set up for the Battle of Tewkesbury. By then, the sun was high and the temperature hit 105°F.

When the water pump broke down, 300 increasingly angry men in armor milled around cursing under the blazing sun. After repairs were completed, the ground rapidly became a quagmire. Some of the extras reportedly wore paper mâché armor, which quickly deteriorated. Three days after this fiasco, Lee brought the extras back for another try, but soon gave up because of the heat.

Ford Beebe, Universal's serial producer-director, was brought in to do pickup shots and more warfare scenes. Somebody came up with an idea to rescue the battle scenes by intercutting new foreground action against the process backgrounds of the original scenes. While not as spectacular as the original concept, the resulting montages are artistically appealing.

Costs had mounted to the extent that Lee was ordered to omit the wedding ceremony of the baby Prince Richard and Lady Mowbray. He finally was allowed to shoot the sequence, an impressive bit of pageantry, after promising to hurry the remaining scenes with the higher-paid players. After principal photography wrapped on September 4, ten days over schedule and about $80,000 over budget, Beebe was still making pickup shots. The studio chiefs were livid; unlike the other major studios, Universal didn't own a chain of theaters to play their own product, and therefore couldn't afford the huge budgets lavished by MGM, Paramount or Fox.

Musical director Charles Previn and composer Frank Skinner had decided to use the quaint styles and motifs of 15th-century music for the score. Hans Salter, a composer-conductor recently arrived from Germany, had assisted Skinner on the celebrated Son of Frankenstein music and was further involved in scoring Tower of London. Much of the music was played with period instruments, such as the recorder, the tiny spinet harpsichord, the viola d'amore and the viola de gamba. Triumphal marches were scored for trumpet, drums and male voices.

At a studio screening only a few days before the scheduled November 17 release date, company executives complained that the gentle music was inappropriate for a picture they intended to exploit as horrific. Previn was ordered to provide a full-blooded, menacing score. Lacking the time needed to compose and synchronize so much original music, Skinner, Salter and Previn worked around the clock rearranging music taken mostly from Son of Frankenstein. For example, the famous theme for the Monster's walk, paced more slowly, is equally effective for the measured tread of the club-footed Mord as he stalks through his dungeon. Skinner also utilized his love theme from the Charles Boyer-Irene Dunne drama, When Tomorrow Comes (1938), and some action cues from The Sun Never Sets. It all works very well. Unfortunately, the very recognizable hand-me-down cues which were being recycled into B pictures and serials even then along with leaks about the so-called "cardboard" armor, led to the idea, expressed by some historians, that the picture was made cheaply.

A few portions of the abandoned first score remain. The longest segments are the battle marches. The 20-voice St. Brendan's Boys Choir of Los Angeles sings traditional music for ceremonies at St. John's Chapel. Light period music is heard in a sequence involving Queen Elysabeth and the baby princes. The excised "Anne Neville Suite" surfaces in the 1940 sci-fi serial Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe.

Despite some bad press, Tower of London has aged well and holds its own as a handsomely staged, beautifully acted picture from a vintage year.

For access to more than 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.