Dark Majesty: The Rise of Maleficent

Dean Semler, ASC, ACS, enters the realm of an evil icon this live-action take on the classic Disney villain.

Unit photography by Frank Connor. Photos and frame grabs courtesy of Disney Enterprises, Inc.

Everyone likes a good villain, and Maleficent, from the 1959 animated film Sleeping Beauty, is perhaps Walt Disney’s most iconic. Feared and reviled in equal measure, the self-declared Mistress of All Evil is finally having her side of the story told in the live-action film directed by Robert Stromberg and starring Angelina Jolie in the title role.

Before she began covering herself head-to-toe in black, Maleficent was a winged fairy living in an idyllic natural world. Her peace was shattered when an invading army of humans threatened her home. Rising to the land’s defense cost Maleficent both her powerful wings and her happiness. Afterward, corrupted by the desire for revenge, she places the well-known curse on Princess Aurora (played as a toddler by Vivienne Jolie-Pitt, and as a young woman by Elle Fanning). While biding her time until the curse takes effect on Aurora’s 16th birthday, Maleficent begins to suspect that the young woman may be capable of bringing peace to the kingdom.

Cinematographer Dean Semler, ASC, accompanied Stromberg for the director’s first feature. Asked if he particularly enjoys working with first-time directors, Semler responds, “I just enjoy working! It is always the director’s film and I love being able to offer as many ideas as I can. Perhaps that occurs more often with first-time directors, but it’s their vision that is up on the screen. The director is the one and only captain of the ship; cinematographers just man the oars to keep smooth sailing.”

Semler found Stromberg meticulously prepared for the complexities of combining the live-action photography with extensive visual effects, the latter of which were supervised by Carey Villegas. “The moment I walked into Rob’s ‘War Room,’ there was the whole movie covering the office walls in 36-by-18-inch prints of conceptual drawings and storyboards,” he recalls. “I was thrilled — the clarity of Rob’s vision made it easy for everyone, especially me!

“The depiction of light was exciting,” Semler continues, “the way the huge castle windows were single-light sources, how the walls receded into moody shadows, the importance of fire and candlelight, how the exterior sets could be brought to life with backlight. When I timed the film many months later with Yvan Lucas at EFilm, those images on the office wall were alive on the screen.”

Semler reports that Stromberg’s previous experience in visual effects and production design was particularly advantageous. “He was still directing actors, of course, but he could also clearly see way beyond what was on the video monitor. He’d frequently say things like, ‘Don’t worry about that cherry picker or those lights in shot. When we take them out later you’ll see a beautiful waterfall with fairies skimming across the water.’”

After conducting comparison tests between the Arri Alexa, Panavision Genesis and Sony F65, the filmmakers decided the Alexa best suited Maleficent’s extensive visual-effects requirements. Any misgivings Semler may have felt about abandoning the Genesis — his camera of choice since Click (2006) — quickly dissipated. “I believe that images from the Genesis still look the closest to film, but only by a tiny degree,” he says. “I loved using the Alexa; it’s a great camera. I was able to slightly shift the color temperature in-camera, usually by 100 to 200 degrees — a simple and subtle but incredibly effective tool that I used a lot.”

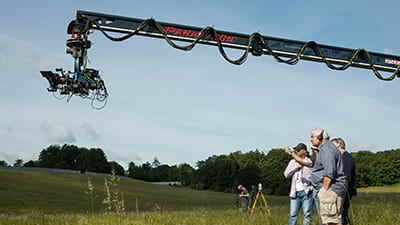

Maleficent’s main unit carried three Alexa Pluses, rented from Panavision London. (Semler liaised with Panavision’s Hugh Whittaker, whom he describes as “a tremendous support throughout the whole movie.”) To negotiate the enormous sets, the A camera spent most of its time on a Libra head on a 50' Technocrane, while the B camera was often on a dolly. The cameras were rated at their native 800 ASA, and Semler shot both interior and exterior scenes between T2.8 and T4, using NDs as necessary.

For on-set monitoring, Semler used EFilm’s ColorStream system, as he has on every digitally acquired film he’s shot since Apocalypto (AC Jan. ’07). “I didn’t want to be endlessly fiddling around with LUTs on the set,” he explains. “I know cinematographers who do many LUTs for a variety of purposes — day, night, day-for-night and so on — but I prefer to have parameters that remain the same throughout shooting and into post. It’s the same theory as when I used to shoot film back in [Australia] and always had my printer lights set at 25 across the board.”

The ColorStream process tone-mapped the Alexas’ ArriRaw output into DCI P3 color space, and then a second LUT emulated that look as closely as possible in Rec 709 for monitoring. The workflow, which is part of the services of EFilm and Company 3’s combined EC3 near-set offering, also included additional fine-tuning for specific monitor characteristics. Semler semi-regularly viewed dailies on an iPad after making an initial visit to Company 3’s dailies facility in London, and he also checked in with the EC3 near-set dailies station, but he reports that he was ultimately confident with what he saw on the monitors on set.

The ArriRaw signal was recorded onto Codex drives sent to the EC3 near-set dailies setup, and the files were then archived along with the metadata to a SAN and sent to Disney for upload. Editorial received DNxHD versions via upload to a secure, cloud-based network. The visual-effects vendors deBayered the ArriRaw, adding the required visual effects and performing a layer of color work. DPX files and metadata then went to EFilm in Hollywood, where Lucas worked with Semler to time the DPX files in the company’s Lustre-based, proprietary color corrector.

In front of the Alexas, Semler opted to work with spherical Panavision Primos, his favored lenses for many years. “Same, same, same,” he quips. “My lens kit doesn’t change from film to film. There is a set of primes starting at 14.5mm, going through to the 150mm. I also tend to use [Primo] zooms quite a lot. The hero lens on A camera was the 17.5-75mm [T2.3], and the 11:1 [24-175mm T2.8] zoom sat on the B-camera. I also used ‘The Hubble,’ Panavision’s 3:1 [135-420mm T2.8] zoom. We always tried for two cameras and often used three. Two cameras shot different sizes from a similar angle, while the third was hidden somewhere [or] placed on the ground with the 14.5mm, getting a wide shot.”

Principal photography for Maleficent began in mid-2012 at the Pinewood Studios facilities located west of London. The action for the film occurs mainly in two worlds: the morally murky land of the humans, which is dominated by the cool tones and deep, rich shadows in the castle of King Stefan (Sharlto Copley), and the Moors, the colorful, sparkling forest home of the fairies, pixies and other fantastical creatures. Sets for the huge, looming castle were built on several of the soundstages, while much of the Moors was filmed on an exterior set on the Pinewood “back paddock,” as Semler calls it.

In order to realize the intricate level of detail required in both the practical sets and CG environments, the production brought aboard two production designers: Gary Freeman, who has a practical set-building background, and Dylan Cole, whose forte is digital design. This pairing made perfect sense to Semler. “Gary and Dylan worked almost as one person,” he says. “The giant castle interiors, such as the Great Hall, almost burst out of the stages and were resplendent with detail. Stone walls, staircases, windows, polished floors — everything was such a pleasure to light. And the digital creations were equally stunning.

“Rob insisted on the use of a light smoke throughout all the sets, interior and exterior, which surprised me a bit,” continues Semler. “Usually the visual-effects people don’t want smoke because it contaminates the bluescreens, which we used instead of green due to the amount of green foliage in the sets. I was happy because the smoke gave me the opportunity to create beautiful beams of light!”

Eddie Knight was the initial gaffer on Maleficent, putting the show’s lighting plans and systems into action. “Eddie is very thorough and creative, with invaluable experience working the Pinewood stages,” says Semler. “He and his loyal team of electrics and riggers, including his four sons, made my job relatively easy. Sadly, Eddie had to leave the show for personal reasons. My longtime U.S. gaffer, Jim ‘Jiminy Cricket’ Gilson, then joined us, fitting in well with the London lads.”

Knight and his crew rigged Mole-Richardson space lights in the ceilings of each stage that housed a castle interior. Half the space lights were left clean to provide ambience for the daylight scenes, while the second half had a combination of 1/2 CTB and White Flame Green gels for night or dusk ambience. Lighting-desk operator Graham Driscoll used ChamSys’ iPhone application MagicQ Remote to quickly change from day to night looks.

Tungsten 20Ks, 10Ks and Nine-light Maxi-Brutes positioned in the overhead grids served as either sun or moonlight, depending on the scene. “All the castle sets had huge windows, which I used as single sources, deliberately letting the shadow areas go,” Semler explains. “For soft fill light the boys would fly several 20-by-20 Ultrabounce rags and light them with a diffused 20K.” 5K Mole-Richardson Pars created beams through the smoke when required. Additionally, to replicate light coming from a huge skylight in the Great Hall, Semler used several 18K Alpha HMIs made by K 5600; the lamps’ ability to run while pointed straight down at 90 degrees meant they could be rigged and simply left in place.

Fire and candlelight also feature prominently in the castle. To supplement the effect, Knight designed 2'-square panels that each contained 36 GU10 halogen lamps, six lamps per channel, all controlled through a dimmer. “These ‘Mini-Maxi’ fixtures were used a lot, positioned just out of frame, for firelight, candlelight and other purposes,” Semler recalls. “It’s the best fire-effect rig I’ve ever used.”

One of Semler’s favorite sets was the Pixie Cottage, where the infant Aurora is taken for protection. “I just loved the hilarious scenes [in that set], with the three pixies played by wonderful English actresses [Juno Temple, Imelda Staunton and Lesley Manville],” says Semler. “The space was around 12-by-12 feet, and it had quite a low removable ceiling with immovable beams that were challenging to work around.” The working conditions were further complicated by the need to have rain and lightning effects inside the cottage as the pixies come under attack from Maleficent. With rain bars creating the downpour, a 40K Lightning Strikes unit played through double ND.9 gels for a lightning effect that registered properly with the Alexa’s sensor.

For day interiors in the cottage, Semler’s crew aimed 10Ks and 20Ks with 1/4 CTO through the set’s windows and doorways, and bounced Source Fours within the set. Any wall that was not in the frame would be pulled out, and soft sources created with 1K Pars and 5Ks would push additional light into the set. Gilson also added paper lanterns to provide flicker effects from candles.

In some instances, the use of interactive light became a source of on-set humor. “One of the funniest moments on set was when Elle, as Princess Aurora, is brought to the fairy forest and sees the happy, sparkly, glowing little creatures for the first time,” recalls Semler. “Rob wanted to use some interactive lighting on Elle because the digital pixies he’d be creating later would be glowing. So three big blokes from the electrics department enthusiastically waved 200-watt bulbs on the end of blue painters’ poles inches from Elle’s face. Like a true professional, she ignored the hairy men and enjoyed the little lights.”

When it came to exterior shooting on Pinewood’s Paddock Lot, Semler was understandably loath to place himself at the mercy of England’s fickle and often overcast weather. To provide control over the exterior conditions, chief rigger Bill Beenham and his team erected a 200'x80' sheet of tough black trampoline material supported by four 50' steel towers. “The Moors set underneath the tarp was huge and very impressive-looking,” says Semler. “It had a waterfall, little pools, a small lake, pathways, beautiful big trees covered in moss. It was lovingly prepared by the wonderful greens department, trampled by the crew during the day, and then thousands of blades of grass and flowers were patiently redressed in time for the next day’s shooting. The Moors is where the fairies live, so it had to look dazzling and alive. That fantastic set would have looked horrible if left to the mercy of high summer sun, and an overcast sky would have flattened the image, sucking all the life from it.”

Beneath the cover, a range of HMIs, including 12K Par spots and 18Ks, were used as backlight, creating beams through the light smoke. 12K Pars with the lenses removed to create “a very narrow beam of light that’s uncontrollable because it’s so hot,” says Semler, added visual punch to certain areas of the set. Fill light was provided by 4K, 6K or 18K HMIs behind a 4'x4' frame of 1/4 Grid Cloth that spread the light evenly onto a 12'x12' frame of Full or Light Grid Cloth. “It’s a very soft fill light that is kind to the actors,” the cinematographer notes. A modified Wendy Light was also used on the Moors exterior set; the tungsten fixture was rewired to take 196 full spot globes, and was used during day scenes to create a hot, warm backlight on Maleficent.

In general, Semler steered clear of dark, moody lighting for Maleficent, instead opting for a simple, direct and flattering look. Backlight brought out the famous horns and provided highlights to Jolie’s glossy black costume and flowing cape, while her key light was often, but not exclusively, a Source Four from over the camera. “Maleficent was lit as a beautiful lady,” says Semler. “I did some early tests using side light, but neither Angelina nor I liked that as much as the front light, which brought out the color of her eyes, and beautifully delineated her features and the fantastic prosthetic cheekbones made by Rick Baker.” 1/4 to 1/2 CTB was added to Jolie’s key light to keep her skin tones on the cool side.

Semler credits Maleficent’s second-unit crew, led by director Simon Crane and cinematographer Fraser Taggart, with undertaking large portions of both the interior and exterior work. “They had difficult circumstances to work in and I really have to thank those guys. Fraser’s work matched the main unit’s seamlessly.”

The second unit carried a kit of four Alexa Pluses, and an additional two or three were brought in when shooting larger sequences. The need for extra cameras was often determined more by logistics than coverage considerations, as Taggart explains: “There was such a variety of camera rigs on second unit that a camera and grip pre-rigging crew was needed to prepare equipment for the next setup. For example, we might be moving from a handheld sequence to a Technocrane sequence to a dolly setup. We always leapfrogged equipment ahead to get as much as possible out of each day.”

The sometimes-aggressive camerawork required for the second unit’s battle sequences stood in contrast to the main unit’s propensity for elegant moves. A pertinent example occurs early in the film when Prince Stefan’s father, the ill-fated King Henry (Kenneth Cranham), leads his troops against the magical inhabitants of the Moors, who in turn are led by Maleficent. Semler used a Russian Arm to capture sweepingly majestic images of Henry’s troops as they approach through gently rolling hills. The second unit then took over as hostilities escalate into open conflict, capturing the action with strident moves on Technocranes that lead into handheld cameras amid the battle proper. Taggart used longer lenses to ensure the images were filled from foreground through to the background. The 85mm Primo, for example, was often used for what the cinematographer terms “long wide” shots.

because of the extensive foliage in the sets.

The penultimate battle between Maleficent and Stefan begins in the castle’s Great Hall. After escaping a trap set by the king, Maleficent turns her familiar, Diaval (Sam Riley), into a fire-breathing dragon, and the castle rapidly becomes a raging inferno. “The castle set was beautiful,” recalls Taggart, “so we burnt it down.” The special-effects department had several methods at their disposal: gas pipes built into the set allowed for a selective, controlled burn; a flame-thrower with a range of 30' served as the dragon’s incendiary breath; and kitty litter soaked in accelerant created a slow-burning rain of fire.

Nine-light Maxi-Brutes with Full and 1⁄2 CTO provided firelight effects throughout the set. “The combination of practical fire effects and the flickering light on reflective surfaces such as the soldiers’ armor and the sweat on their faces brings the images alive and really sells it to the audience,” enthuses Taggart. “If they see actual flames in shot, the electronically controlled flickering light isn’t noticed.” Fill light, Taggart adds, wasn’t required for this sequence. “The images were kept quite moody to let the firelight get into the shadow areas so that it read well.”

Semler has nothing but praise for his crew. “My English crew was fantastic,” he says. “Many are veterans of large-scale productions such as the Harry Potter and James Bond franchises, so they were completely at ease on a production the size, scale and complexity of Maleficent. I wish I could mention every single one of them. A-camera operator Gary Spratling and first AC John Ferguson headed up the camera team. Steve Evans was my unflappable digital-imaging technician. Elliot Purvis, whom I first worked with in Budapest on Angelina’s film [In the Land of Blood and Honey], was the central loader. And Johnny Flemming was my key grip; we had first worked together as young lads more than 20 years ago on The Power of One, shot in Africa.”

Despite Maleficent marking the 19th feature Semler has completed with EFilm, there was a surprise in store for the cinematographer. “Neither Yvan nor I had seen any of the visual effects, which make up a huge part of Maleficent,” Semler notes. “I was dumbfounded watching the brilliant images and creatures created by Rob and his team. Having said that, my work still plays an essential part within all the digital imagery. The basic principles of cinematography remain the same: the director’s vision has to be fulfilled, the screenplay has to be transformed into moving images, and the sets and, most importantly, the actors have to be lit. I’m really proud of what we accomplished on Maleficent.”

Jolie presented Semler with his ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2013. He presented her with the ASC Board of Governors Award in 2018.

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS

2.40:1

Digital Capture

Arri Alexa Plus

Panavision Primo