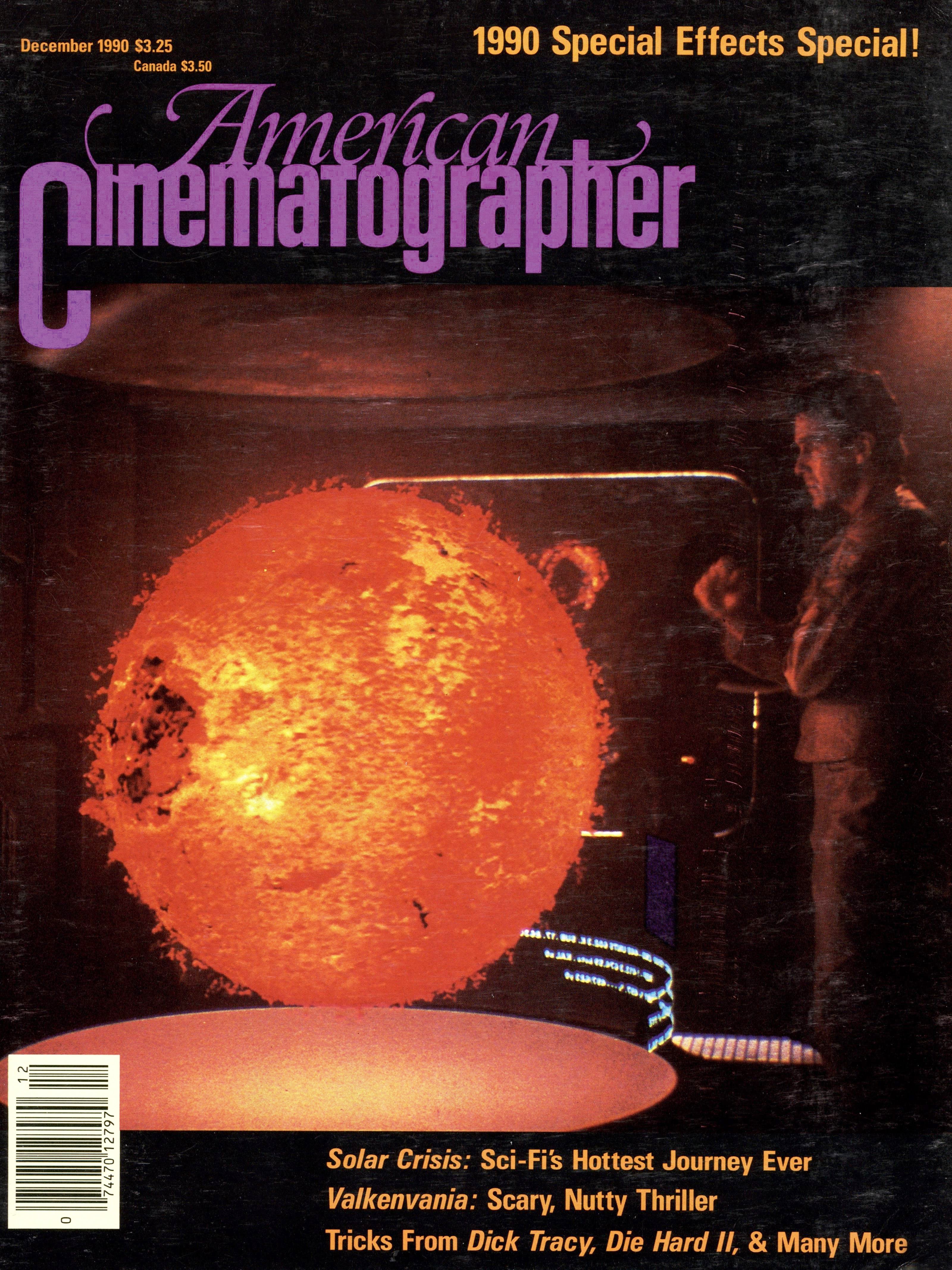

Die Hard 2: Terror Takes to the Skies

Industrial Light & Magic airplane miniatures work wonders in this big-budget Yuletide thriller sequel.

"Miniature" is a relative word. It can mean a painting the size of a postage stamp, an engraving on the head of a pin, a cityscape that fills an entire studio stage. In the making of motion pictures the word often seems a contradiction in terms, especially when miniature action is staged on such a grand scale as the flying aircraft scenes of Die Hard 2.

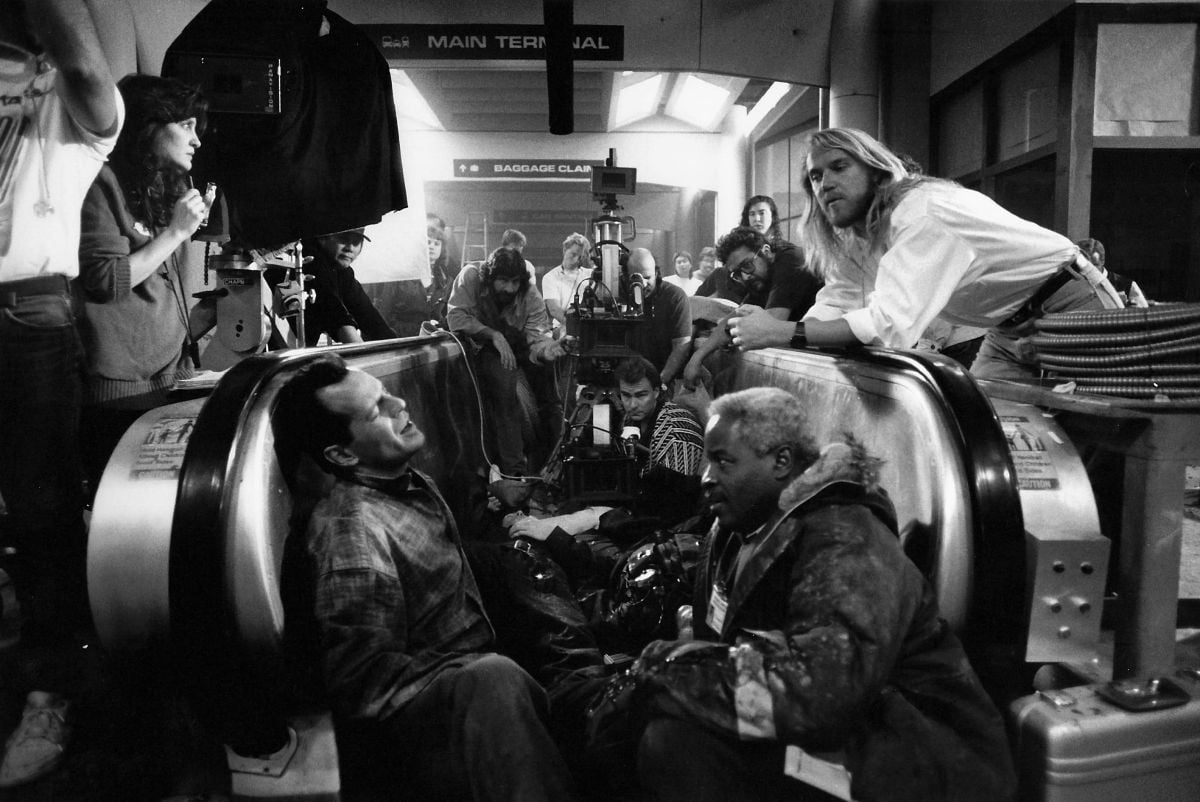

These sequences, which feature some of the biggest and most convincing work of its kind in years, were produced at Industrial Light & Magic, the visual effects division of Lucasfilm Ltd. Michael J. McAlister was visual effects supervisor for the show, overseeing a large crew of artists and technicians for a hard-fought six months to put a remarkable assemblage of exciting images onto film.

Although still young, McAlister is a seasoned pro at his trade. A cum laude graduate of the USC film school, he began at ILM as a camera assistant on The Empire Strikes Back in 1980, graduated to operator on Dragonslayer, became a director of photography on Starman, and has been visual effects supervisor on a half-dozen big features including Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade in 1989.

"In most cases our miniature work for Die Hard 2 was like a second-unit operation rather than a traditional special-effects job," McAlister emphasized. "The reason for going that route was the need for realism. With so much interplay between the airplanes and clouds and with all the explosions, we wanted to use the largest models that we felt were practical as well as economical to build, handle and transport."

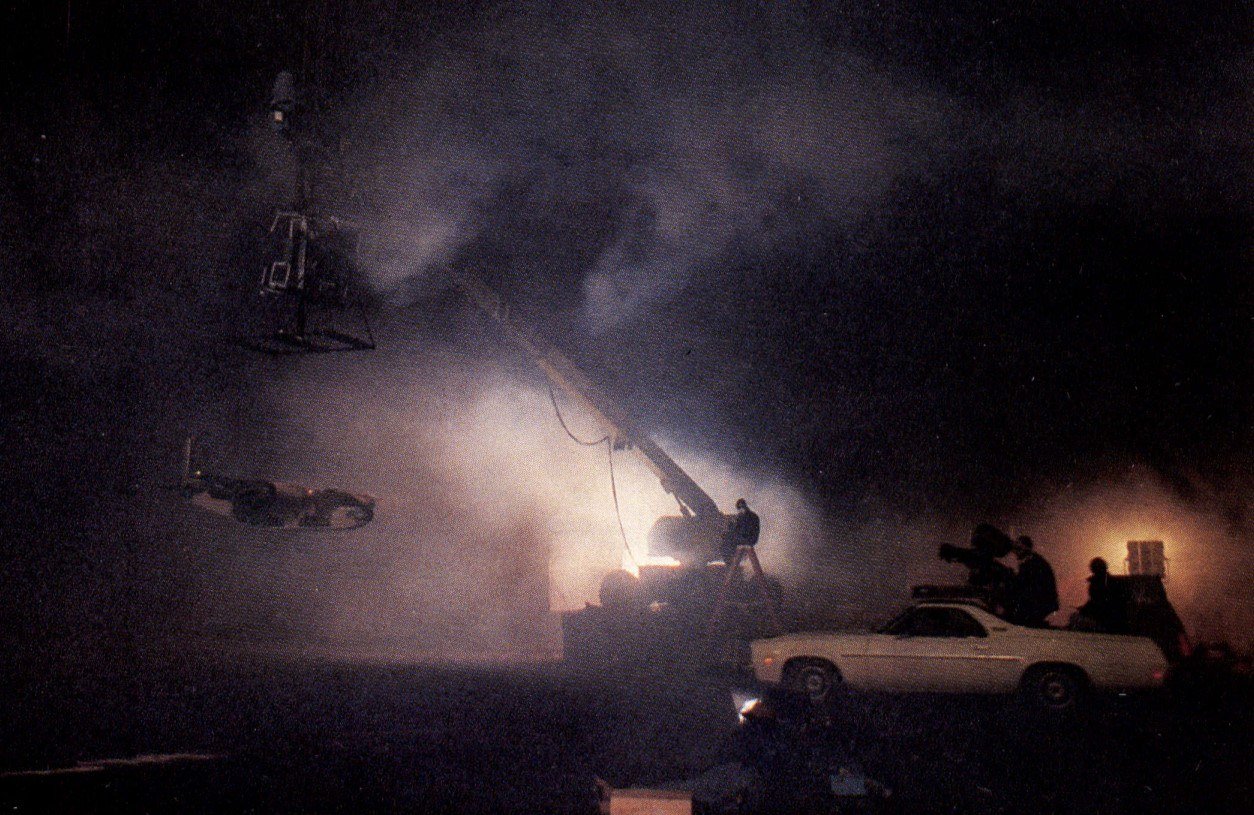

These scenes were photographed at the California desert town of Mojave. "They have a big airport there that isn't used very much, and they were willing to close down one of their taxiways and give it to us for about four weeks," McAlister recalled. "We had an enormous unit with about 65 people, partly because we used multiple camera crews. We had tents, semi-trailers and all kinds of equipment, special effects machines, and motor homes where we could get out of the dust. It was a grueling shoot. Sometimes it was freezing cold, sometimes we could run around all night in short sleeve shirts. When the wind blew there was dirt everywhere.

"I enjoyed the camaraderie; it was like a sports team coming together. We rehearsed around tables for weeks ahead of time — all the modelmakers, the stagehands and the pyro guys knew what we were going to do, so we were well prepared to go out into the desert. Once we got there and started shooting, I tried to make sure that I got to bring the dailies back from L.A. Since we were shooting in 35mm and 4-perf, once it was filmed and they accepted it, it was theirs — they just cut it in."

At first it was difficult to convince the production executives that the effects personnel needed to see the films, for morale as well as practical reasons. "I forced the issue a few times and told them that I couldn't give them the film yet because I had to take it back and show it to the crew, so they could see what they were doing," McAlister said. "After a couple of days of bringing the film back the crew really realized they were making something special; it brought them closer together and made them want to work even harder."

“That’s the nice thing about having so many different avenues to create effects — we’re not limited in what we can accomplish.”

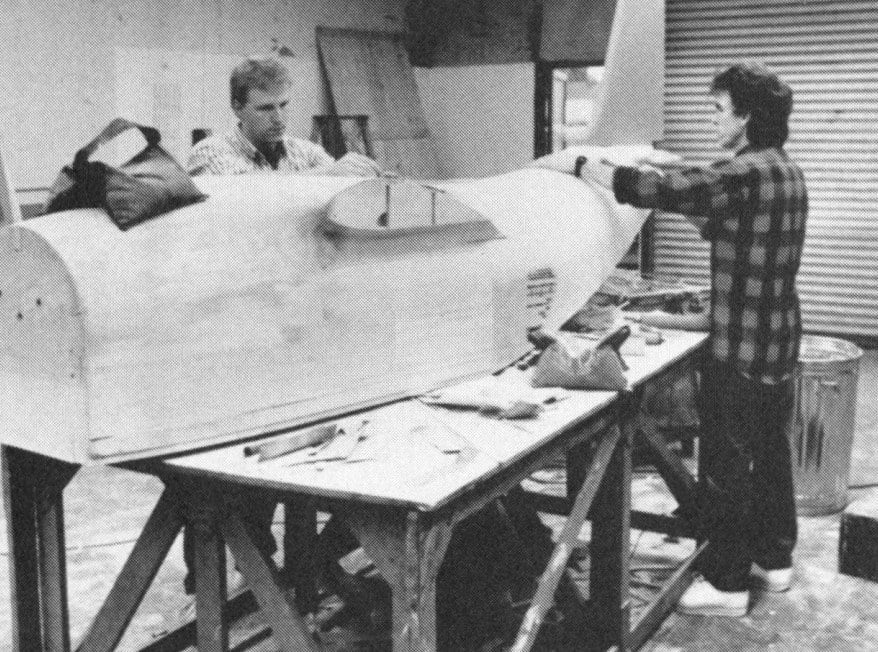

The contention that miniature is a relative term takes on strong meaning when the sizes of the aircraft assembled at Mojave are considered. "The smallest airplane we used was the C-130, which had a 14' wingspan," McAlister recollected. "They ranged up to a 747 model with a 20' wingspan and a 24' fuselage. We also had a DC-8, a 727, and an L-1011 which we used for three different airplanes by simply repainting it."

With the current emphasis on motion control technology, blue screen compositing and other highly sophisticated methods, modern visual effects experts rarely employ the intricate wire work with which such past masters as John Fulton, ASC (Vertigo) the Lydecker brothers and L.B. Abbott, ASC staged miniature aerial action. It is refreshing, therefore, to learn that most of the model work of Die Hard 2 was achieved the old-fashioned way, but on a grander scale than was generally considered feasible in the past.

"All the shots of the various airplanes flying in and above the clouds, with the exceptions of the first three views against the sunset, were done by hanging the models from a construction crane that had a special motorized gimbal rig to allow the airplane to pitch and roll," McAlister explained, "The airplanes in the sunset scenes were shot in front of a bluescreen and matted in, using motion control. They were much smaller models, about 3' across.

"We keep re-using old techniques that have been forgotten, bringing them out of the woodwork whenever it's appropriate. That's the nice thing about having so many different avenues to create effects — we're not limited in what we can accomplish. We can look around and figure out what's best for that particular story point, and if nothing exists then we try to invent something."

High-speed cinematography is at the heart of convincing model action. Although there are empirical formulae for determining cranking speeds according to scale, most effects cinematographers deviate from these whenever their instincts so advise. "We used different camera speeds, depending on what the action was going to be," McAlister revealed. "We did an extensive series of speed tests at the studio before we went out into the desert. I decided that when the airplane was crashing but not exploding we would film at about 200 fps, which would slow the action down enough that we could see the airplane flex and the engines wobble. When we actually had pyro going on — pyro is so quick and it moves so fast that you have to shoot faster — we turned at 360 fps, which was the fastest we could go without some highly specialized equipment.

"We obtained the high-speed cameras from Photo-Sonics and shot straight 35mm because all the VistaVision cameras are slow by comparison, going up to only 80 or 90 fps. The Wilcam VistaVision supposedly goes up to 160 fps, but it usually tears up the perforations in the process." At ILM, most work is done in the VistaVision format and optically reduced to fit the standard frame.

High-speed photography demands high-speed film: "We used Kodak 5296 throughout because we had so little light available and everything was being filmed at night. We had rows of 12K HMIs trying to light the scenes enough to get an exposure." McAlister allowed that some trial and error is often necessary in scenes involving pyrotechnics. "We shot the the 747 crash with the bad guys twice," he noted. "We filmed one explosion with four different cameras and everything happened too quickly — the airplane just disintegrated. There were multiple bombs in it and certain delays had been figured out; they just turned out to be too quick. Then we shot it again with a second airplane and increased the amount of delay between explosions. There are three distinct bits of pyro action in that shot. It all looked like one explosion to the eye, but when it's filmed at 360 fps everything lasts 15 times longer.

“We explained very carefully that if we blew up all the airplanes and still didn’t get the shot they wanted, they’d end up with only what they got.”

"We had three models that we planned to blow up if we needed to. Four copies were made off the same mold. One airplane had a really nice paint job for the 'beauty shots' of the plane flying above the clouds. We didn't take the care to paint the others so nicely.

"I originally thought we should have six airplanes, but the producers were willing to take the responsibility of having fewer airplanes in exchange for a lower price," McAlister said, explaining one of the facts of life in the visual effects field.

“Initially, when we're doing a budget and talking to the director and the producer, we try to figure out what they need to see and try to keep the budget down. But we also want to make sure that we have enough models to give them what they want and we have to decide how many models we're going to build. The process of getting this project was very labor intensive and it took us a long time to get the budget where they wanted it. There was a lot of compromising back and forth. Part of the process of paring the budget down was defining further what they wanted to see. We explained very carefully that if we blew up all the airplanes and still didn't get the shot they wanted, they'd end up with only what they got. We can't build another airplane in time to shoot it while we're out there, and it would be enormously expensive to go back.”

"Fortunately, I made all the right decisions as to how to stage the shot, where to place the cameras, how to do the bombs and how much time to allow between each explosion," McAlister grinned. "It worked out perfectly. We worked all night and shot just before sun-up. We hadn't filmed every angle that I had planned to shoot, but the producers and director were so blown away by the footage they were seeing they said, 'You got it! That's all we need.' At that point we had lost a couple of days due to weather, so it surely helped our schedule not to have to shoot it again."

Live miniature action is an exacting science, but not an exact one. "One difficulty when dealing with this kind of pyro work is that a lot of events are unpredictable," as McAlister put it. "We can guess what's going to happen when we blow something up and we can figure out where the camera should be based on what we think will happen. Then we have to just bite the bullet, do it, and see if it turns out right.

"When we crashed the DC-8 — the Windsor Air jet which the bad guys crash purposely — we had seven different pyro events take place during the explosion," McAlister recollected regarding the most complicated crash in the picture. "They were timed out in such a way that there would be enough separation between the explosions so that if the editor wanted to cut away — which he did — he could cut back to a continuation of the action. The camera positions were decided upon according to what was supposed to happen during the individual explosions so that there would be a camera featuring each event. We were lucky on that one; we got it in one take.

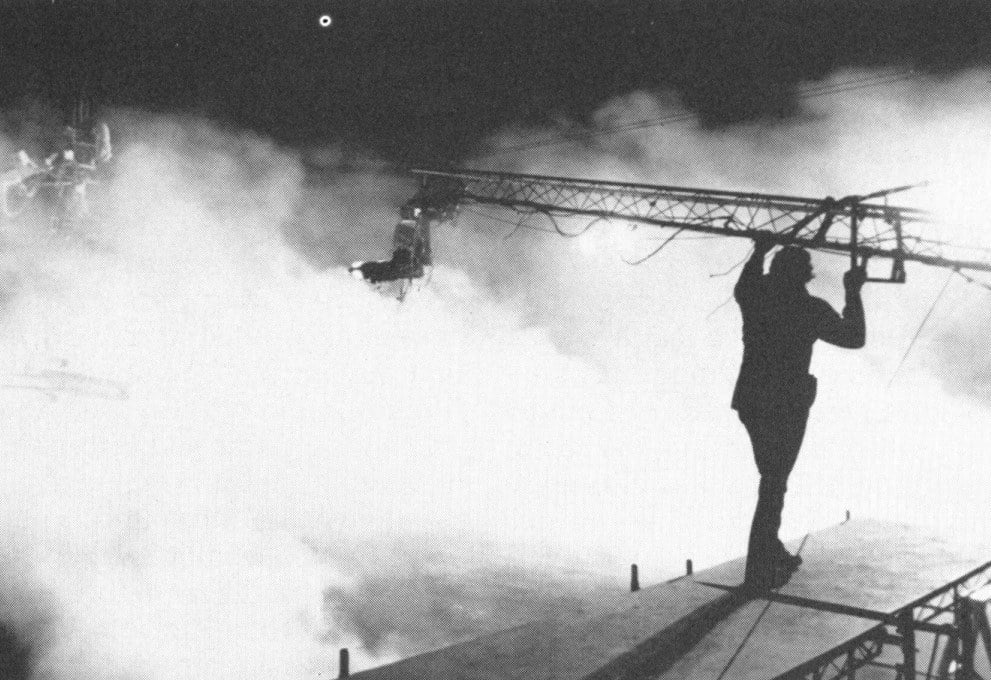

"When we were shooting the flying footage with the airplanes among the clouds we used a 60' crane. It didn't have to be very high in the air because we were not filming wide shots. The idea was to keep the wires as short as possible and still clear the equipment out of the shot. The higher the crane, the longer the wires needed to be, and then the planes would dance around in the wind. It was usually too windy or not windy enough there, but once in a while we'd get just the right amount of wind and we'd shoot fast."

The magnitude of the scenes involving aircraft among clouds was well beyond the capabilities of the typical smoke and fog machines used on stages. "When making the clouds we expanded on an idea that was developed for Always, which involved firefighters," McAlister disclosed. "They obtained large Navy smokers that are used on warships to smoke up the area and hide the ship from the enemy. We laid out a series of big 8" tubes with holes every foot or so. We'd blow the smoke in one end with fans and the smoke would leak out of the holes along the 100' length of pipe. We'd lay that down upwind of where we planned to shoot. If we'd get just the right amount of breeze — somewhere between five and 10 miles an hour — it would create an incredible blanket of smoke as much as a half-mile long before it would thin out. It looks just like clouds or smoke from a fire, depending on how we light it and how thick we make it. It's all mineral oil smoke, so it just dissipates and doesn't stay in the air or hurt the environment."

“There are times where if you really study the shots, you can see that they’re not real clouds — if you know what to look for.”

McAlister mentioned some exasperating moments, which are always to be expected when a company is on location and dependent upon the cooperation of Mother Nature. "If there wasn't enough wind, the smoke would just rise up into the air and then float away; if it was too windy the smoke would move too quickly and boil and agitate too much to look like clouds going by. We got good at working extremely fast when the wind was just right, because we never knew how long it would last. If the wind shifted directions it was necessary to turn all the set-ups around because all the lights were suddenly in the wrong places. The airplanes always had to be pointed the right direction — straight into the wind — or they would appear to be flying sideways.

"The point is that the clouds were moving and the airplanes were, essentially, standing still. Because the camera doesn't know the difference, it looks as though they're flying over the clouds. There are times where if you really study the shots, you can see that they're not real clouds — if you know what to look for. There are other shots where you can't tell, even if you study it."

McAlister enumerated some of the other shots done by the effects unit. One of the best shows the C-130 military transport plane touching down for a landing. "That's the kind of shot you can get for real in live action if you have the airplane," he stated. "There would be no reason to do it as a special effect except that the production company couldn't get their hands on a C-130. They managed to get a C-123, which is the previous generation of that airplane, and they modified it to look like a C-130, but in the course of modifying it they made it so it couldn't fly.

"They could use their real airplane for any shot that didn't involve flying — it could taxi and it could get its nose off the ground, but it couldn't get airborne. The shots we had to do were of it above the clouds and the shot where it makes its final approach — it comes right down to the runway and just touches the ground. We used our 14' model and Dave Heron, our mechanical effects supervisor, and his crew built an elaborate wire rig somewhat like an aerial tramway. We had an enormous forklift on the right and another on the left and we strung huge cables between them and made them very tight. We built a marionette rig that ran along those two cables on pulleys, and from that rig were wires that went down to support the airplane. As the plane descended from the sky on its final approach it had to be nose low, then as it landed it needed to flare out and the tail had to go down and the nose had to go up so it touched down. Dave created an instant wire rig to make the plane change its attitude as it touched down. Of all the shots in the movie that's probably the last one people will imagine was a special effect because it looks so real.

"The runway was supposed to be covered with snow," McAlister continued. "In order to make it look as if snow was being kicked up when the wheels touched the ground we hid a fire extinguisher inside the model and hooked up the solenoid triggers, which were operated with radio control. Just as the wheels touched the ground a stagehand would operate the fire extinguisher and C02 would blow out of the wheel wells so it looked like snow was kicking up. We also used a lot of ambient smoke in the air to represent fog.

The usual problems of matching miniature shots to the original live action photography were multiplied because of the schedule. "The first and second units ran all over the country looking for snow" according to McAlister. "For some reason it was a warm winter and all the places that are usually buried in snow had no snow at all. They went to Moses Lake, to Denver, to two cities in Michigan — the result was that they were two or three weeks behind schedule. We had decided to go to the desert at a certain date, and we were locked into that date — we needed to get the shots made in time, and also because of the logistics involved in securing the location. So we had to go out there whether they had shot their footage or not.”

"Fortunately, they ended up finding the snow in northern Michigan,” McAlister said. “They were filming two days ahead of where I was supposed to be filming. We'd work all night. Every day I would sleep three or four hours and then get driven to Los Angeles. I'd look at the dailies that were shot a couple of days before in Michigan, to find out how I was supposed to light and fog the scenes we were going to shoot that night.

"The weather conditions were changing every day, so it wasn't safe to assume that what it looked like yesterday would do for today as well," McAlister emphasized. "If we had gone to the desert in Arizona or New Mexico or northern California I wouldn't have been able to go into L.A. everyday, and there would have been mismatches in photographic style and everyone would have known something was off.

"I enjoyed doing Die Hard 2 because the type of effects I enjoy doing the most are the ones that can become invisible, that people will think were done for real. It's sort of a Catch 22 because if you do your best work nobody will know you worked on the film, and they say, 'What miniatures? What effects?' It's a great compliment but at the same time you want your work to be appreciated, so you want the audience to be sophisticated enough to know you worked on it."

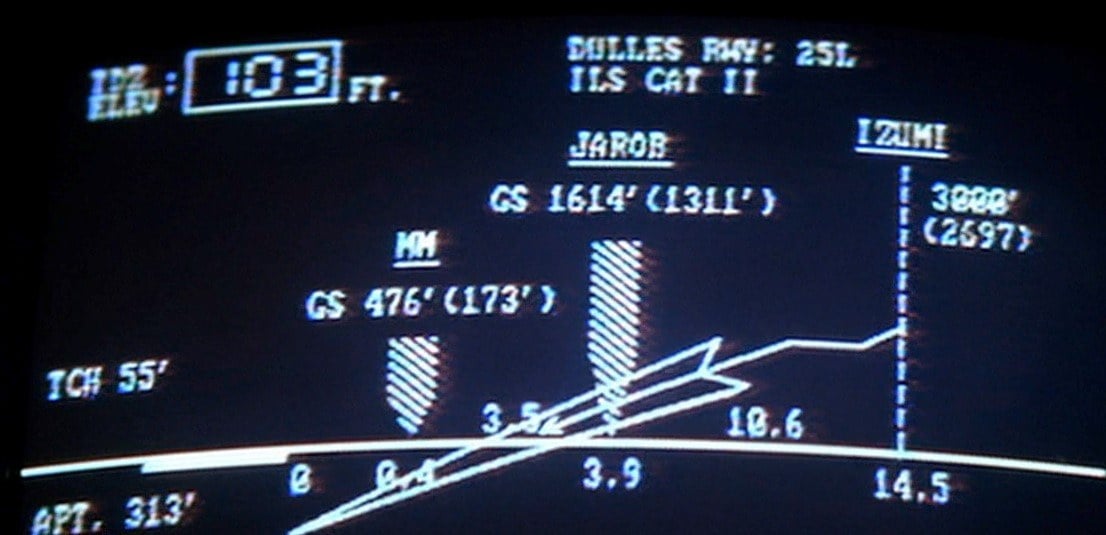

There is a highly realistic scene near the beginning of the picture in which the runway lights are being turned off by the terrorists. It appears to be a telephoto shot looking down the side of a runway and we see all the runway lights stacked up one on top of the other in very sharp perspective. "That's another shot that could have conceivably been filmed in real life if they'd had a runway that was covered with snow and if it was snowing and if they had all the time and money to light the scene and if the runway lights would turn off sequentially instead of all at once," McAlister enumerated. "The director was adamant about them turning off sequentially. So we used forced-perspective models. It was a fairly large miniature that occupied 1,000 square feet of space. In the very foreground was a full-sized runway light that we had obtained, and in the distant background we had a light that was about an inch tall. It was filmed on a small stage in Richmond, and it looks absolutely real even to all of us who know all the flaws in all the shots and can pick them apart. Kim Marks, who is the director of photography on the effects, did a phenomenal job of lighting all these miniature shots.

"There's another scene where the bad guy's plane is coming in for a landing. His window has been shot out and he's freezing cold, so he doesn't want to circle around to the other runway. He tells the people on the ground that he wants to change runways. The camera starts looking at one runway when all the lights are turning off, and then pans to the right as the new runway lights turn on. That was also a very large-scale miniature set."

The depiction of falling snow becomes complicated when miniatures of varying sizes are involved. "Sometimes we used shredded plastic, which is what they use in Hollywood," said McAlister. "It comes in different sizes, and as long as we were working in a large enough scale we could get away with it. I went to Safeway, looked at every shelf in he store, and bought everything that looked like white flakes — laundry flakes, mashed potato flakes, salt, cornstarch — everything! I came back with about 20 boxes of different things and we tested all of them, to see how fast they would fall, whether they looked white enough, and so on.

"We settled on a combination of Ivory Snow and potato flakes. The problem with the laundry materials is that a lot of dusty residue stays in the air and gets in your eyes and nose. We used potato flakes a lot in the desert because we didn't want to blow a lot of plastic around that would end up in mouse holes 20 miles down the road. With potato flakes we knew that at the first rainfall the mice would just be eating mashed potatoes for a while.

"In dressing the sets in the desert we used white sand because we needed something heavy that we hoped wouldn't blow around," he added. "We bought something like 100 tons of sand and spread it all out and dressed the set, and a windstorm happened that night and blew it all away. It's amazing how little time it takes Mother Nature to ruin a set!"

“I never liked that shot from a conceptual point of view because it’s something that would never happen in real life... The strange action and the strange camera points of view call attention to the fact that it’s an effects shot, and that requires the shot to be absolutely flawless.”

A scene that creates an enormous audience response is one in which Bruce Willis fires himself out of the pilot's cabin in an ejection seat an instant before the grounded aircraft is blown to atoms. He is shown from a bird's eye POV as he hurtles right up to the camera, twisting and tumbling, just above the crest of a fiery explosion.

"I never liked that shot from a conceptual point of view because it's something that would never happen in real life," McAlister admitted. "When you do things in special effects that could never happen, sometimes it backfires. The strange action and the strange camera points of view call attention to the fact that it is an effects shot, and that requires the shot to be absolutely flawless. Although the shot is not perfect by any stretch of the imagination, I think the audience is so involved in the story at that point that they don't care.

"It took a long time to get that shot just right. Because of scheduling constraints we were required to shoot the Bruce Willis bluescreen element before we shot the element of the airplane blowing up. We were guessing a little bit as to exactly what the lighting and composition should be. In an ideal world we'd always shoot the backgrounds first, but we shot Bruce first and then a couple of weeks later we shot the background.

"The process of making the ejection seat come up toward camera was rather complicated," he added. "We had gotten an ejection seat from the production company and we welded frames on it so it could be suspended from a post. Bruce was strapped into it and motors were connected to the post so the chair would tumble end over end and also rotate as though it were on a turntable. We had a long dolly track — about 100' — that zoomed in to Bruce. He was acting in slow motion because although we were filming at 24 fps, the intention was to drop out certain frames, so the action would be speeded up. It was a coordinating task to make sure that his performance would work at skip-printed speed and get all the movements just right.

"Even with a 100' dolly move the change in image size wasn't nearly enough; he started too big in the frame. So we put the bluescreen footage into a motion-control optical printer and did an overriding zoom on the stage element so that he started out very small in the frame and zoomed up to camera, tumbling the whole time. Part of the thrill of that shot to the audience is the pay-off at the end when they see that it's actually Bruce Willis in the chair and not a stuntman.

"From a compositing standpoint it was probably the most difficult shot in the movie," McAlister conceded. "It's difficult to compare that kind of shot with the second unit type work of the explosions. Both are difficult to accomplish, but the problems are different." Stuart Robertson was in charge of the optical effects unit in which Tom Smith, Keith Johnson, Dave Karpman and Tom Rosseter were key technicians.

Another complex composite is showcased at the end of the picture, a large-scale pull-back involving a wide scene and six varied live-action elements: "We did that as a huge matte painting by Yusei Useugi combined with digital processing techniques that we have developed in the last couple of years. It's the first time we've ever done a digital composite on a matte painting. A lot of people were working in different areas to get the various pieces of the shot to work — some on the zoom back, others on the blends, others on putting the smoke in, others on the color correction, and so on. No one ever saw the finished image until the very last moment, three months down the road, when all their efforts came together in the final composite.

"Which," McAlister added wryly, "they put the end credits over right away and you can hardly see the shot anyway!" (More about this below.)

He was adamant in his preference for visual effects that add to the realism of a film over those utilized in the service of fantasy or science fiction. "For me they offer a more pleasing challenge," he said.

"In a picture like Die Hard 2, in which you're simulating reality, you have to study what reality is and then recreate it."

Computer Imagery Enhances Die Hard 2

By George Turner

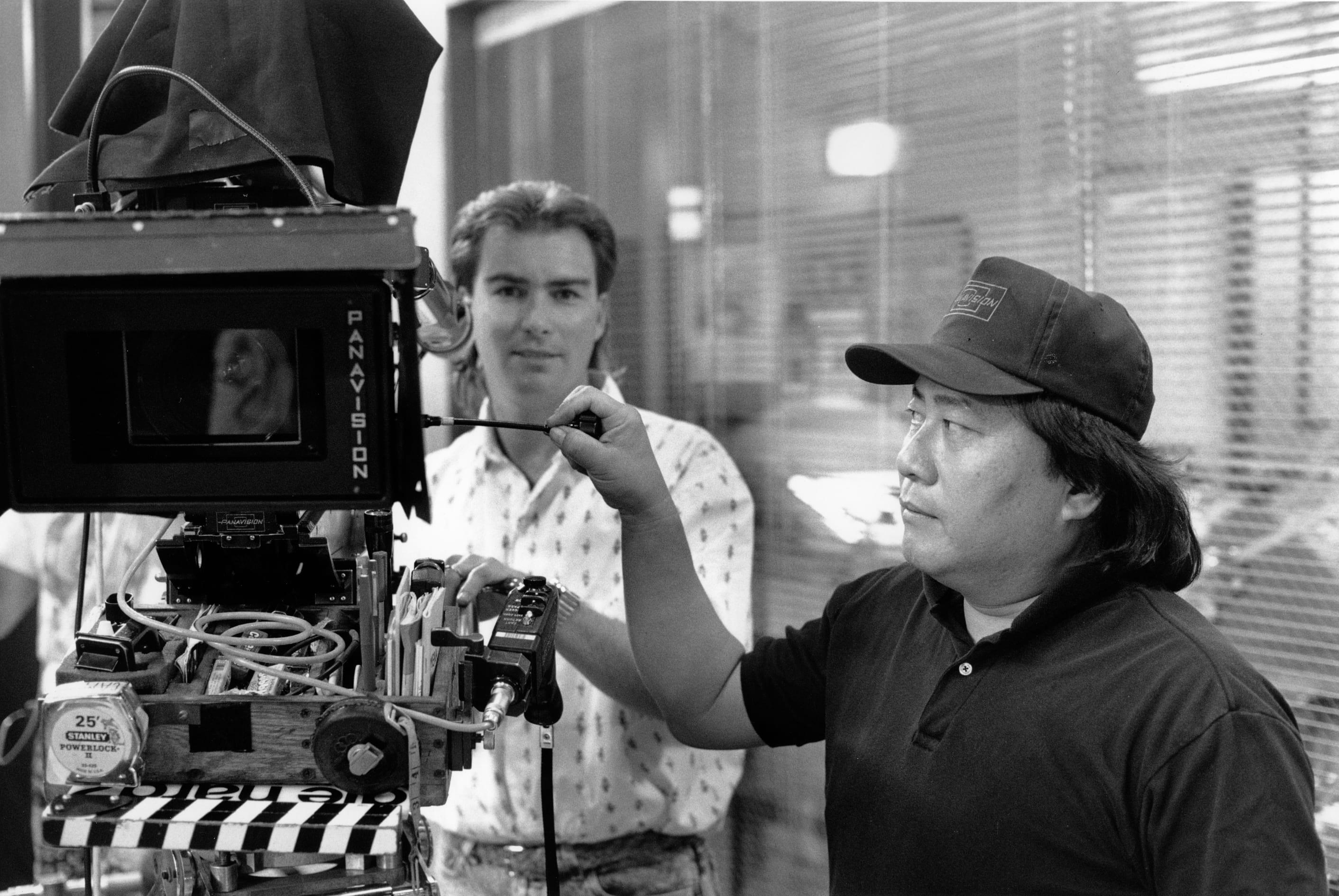

"I don't really have an official title," Doug Smythe said of his job at Industrial Light & Magic. "If I could get one it would be a mile long. Probably the best description would be computer animator and software engineer, because I do programming, animating, modeling, lighting and rendering — as do most of the people that I work with." Some of his most unusual computer animation to date can be seen in Die Hard 2.

Smythe, a Berkeley grad with BA in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, works in ILM's Computer Graphics Department where he writes tools and systems as well as contributing to the visual effects of an impressive number of big features. He also was heavily involved in the creation of "Body Wars," a popular Disney simulator ride.

"For Die Hard 2, computer graphics were used for two types of effects," according to Smythe. "The first is loosely termed 'wire removal' which means that we remove visually any cables, wires, supports or struts that were used to hold up or suspend a model from a rig. The basic idea is that we first find the wires in the images and then, by rotoscoping over the wires on key frames, the computer is able to in-between the positions and figure out where the wire probably is, and we can progressively refine it up until we have a matte which tells where the wire is. The second phase is to remove the wire by smudging the colors across on either side of the matte to fill in the areas.

"We also do some other minor things like filling in and replicating the film grain across the repair area so it doesn't stand out. This was done on about a dozen shots, mainly with model airplanes flying through the air or landing at the airport, and when they were crashing and burning. Those shots were rather difficult because the cables snapped when the planes landed and they were bending and flying around in all directions, so it was hard to track the path and motion of the cables.

"This effect was first done, at least by us, for Back to the Future II and III, and for The Hunt for Red October," Smythe recalled. "It's now pretty much a mainstay of our effects repertoire. Nowadays, in the pre-production stages when shots are being planned out, the people in charge will say, 'Don't worry if the wires show — they can take 'em out later.' It used to be, 'Don't worry, they'll fix it up in optical.' Sometimes it's a bit of a headache, but it's nice to know they're thinking of us, I suppose."

Simple and utilitarian, isn't it? Actually, it is when compared to that second type of computer effect.

An example is a scene officially called MP-4. "This is the scene at the end of the movie just before the fade to black and the title crawl," Smythe clarified. The camera focuses on Bruce Willis and Bonnie Bedelia, who have been loaded on a baggage cart and are being wheeled away, then moves back as though it's on a helicopter to reveal a very wide scene with a half-dozen jumbo jets, dozens of emergency vehicles and crowds of people milling about. There is smoke and steam; lights flash. Ordinarily the shot would have utilized a large matte painting with various rear projected live action segments matted in. This time it was not practical because six different live action elements had to be inserted into the painting. Each of the projected plates would have had to be wedged in and the painting touched up to make a perfect blending — an extra two months work.

“This kind of compositing in the computer has been done here before... But Die Hard 2 was the first time at this facility that all of these different stages were done this way, and this extensively.”

painting. (Photo by David Owen)

The large painting in this instance is the work of Yusei Useugi. Even hanging in a hallway at ILM headquarters it is an impressive sight. In the movie, with the addition of living people and other live elements it is magnificent.

"The painting itself was photographed four times at four different magnifications, each one showing roughly twice the height and width of the previous take so we would have different amounts of information to play with," Smythe said. "Computers work with images in arrays of pixels, each of which is a single color dot. If we were to use only one picture we would either need an extremely large array of pixels to hold enough detail when the painting was zoomed all the way, or we would have to live with low quality images, because when we zoomed in at the beginning only a very small number of pixels would be used for the entire screen and it would look soft or muddy.

"When we did a motion-control move on the different photographs we would cross-fade between them when the one we were zooming back on was just about to reveal its edges on the frame. Inside the painting were six live-action inserts which were filmed on our backlot with instant potato flakes for snow. These had to be match-moved into the pull back of the matte painting. This was done by the effects camera department on a traditional motion control stand to generate the data. Then the data was pulled into computer graphics to replicate the move. Cut-out mattes were hand painted on the Macintosh and this was used to cut out the holes in the painting image and insert the plates.

"A Macintosh II was also used to hand-paint a haze element, which was used to darken the sky in the painting, and to line up the four photos of the painting so that the centers would exactly match when we did the pull back," Smythe continued. "An element was also painted so that the lights on the trucks in the painting could blink, along with a few holdout mattes to control the blinking.

"The steam element representing exhaust from the backs of the painted trucks was filmed on stage by the motion-control cameras. All those elements were scanned into our computers using a CCD camera, which has virtually the same technology as modern video cameras except at a much-higher resolution. These pictures were brought into our system for processing. The paintings had to be zoomed in and out, the live action plates had to be zoomed and repositioned into the painting, and then all the elements had to be composited together."

"None of these were particularly breakthrough uses," Smythe noted. "This kind of compositing in the computer has been done here before, the first example of any significance being Donovan's destruction sequence from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. But Die Hard 2 was the first time at this facility that all of these different stages were done this way, and this extensively. Some of the original elements were created in the computer and a lot more effort and much more processing were applied to the images in the computer than we had ever done before.

"The picture that you see in the theater is exactly what came out of the computer scanner," Smythe disclosed. "The output scanner used in this production is actually a commercial device that you can buy off the shelf. It's called a Solitaire Image Recorder and it has a large screen inside the box which images the pictures one channel at a time — red, blue and green. It exposes directly onto negative film stock, which in this instance was Eastman 5245. Except for the color timing that is applied to all negatives, the release version is pretty much what came out of our system."

Smythe recollected that MP-4 took about two months to complete, from rendering the original matte painting until the final negative and print came back from the processing house. "Most of the work that is actually seen on screen was done in the last week-and-a-half to two weeks of the schedule," he added. "There was a lot of pre-production stuff that had to happen and there were a few late nights. Many of the things we did on this shot could have been done at least as effectively using traditional methods. We wanted to push the state of the art in another direction and see if we actually could do it this way. It was fairly cost effective this time; in the future it may be even more so."

The use of computer graphics has become an increasingly significant part of the ILM product. At this time it remains a small department in terms of personnel. As Smythe described it:

"We have one person who is a full-time operator of both the input and the output scanners as well as being responsible for recalibrating the equipment at both ends. There are two or three other people who do that on a part time or project basis, including one of the optical line up people who has offered to lend his expertise in those areas as well. In fact, we'll soon be moving the digital input and output film scanners into the optical department and they will assume the day-to-day responsibility for that equipment.

"We're trying to get the digital composite equipment as easy, consistent and reliable to use as any of the traditional optical printers," said Smythe. "We give it the pictures that we want to composite, push a button, and then watch and make sure it doesn't blow up. We're not quite there yet, but it's a lot closer now than it was a year ago. The price of computers keeps going down and the speed keeps going up and someday it'll be inexpensive enough that traditional optical printers may be replaced. It may be 10 years, it may be 50.

"There will be some purists out there who'll say, 'You can't replace an optical printer, it's a work of art!' I would agree to that to an extent, but on the other hand, if you have two pieces of film projected on a screen and you can't tell which one came out of an optical printer and which one came out of a digital printer, then I would say 'What difference does it make?' The result should justify the means."

You’ll find our coverage on the work done by visual effects supervisor Richard Edlund, ASC and his team for the original Die Hard here.