Documenting Nature: Cinematography in the Wild

Filmmakers share their perspectives on capturing the natural world.

Killer whales, says Paul Atkins, ASC, are “the most intelligent thing in the sea.” That may explain why Atkins is still alive today.

Weighing several tons and typically measuring up to 30' in length — with interlocking teeth as long as 4" lining their upper and lower jaws — these black-and-white creatures are among the most formidable predators. They hunt in packs and are sometimes called “wolves of the sea.”

Early in his career, Atkins decided to get into the water to film these enormous mammals — commonly known as orcas, which are actually members of the dolphin family — with a 16mm Arriflex SR as they swam up to a beach in Patagonia to feed on sea lions. He trusted in their intelligence and fine-tuned senses not to confuse him with their intended prey in the murky water. “They have an amazing type of sonar,” he says.

The resulting footage, shot with his friend Mike deGruy and produced for the 1990 BBC series The Trials of Life, was described by series presenter David Attenborough as “surely one of the most spectacular wildlife sequences ever filmed.” It won Atkins a BAFTA and helped establish his career as a nature cinematographer — largely because, as he says, “nobody had ever seen anything like this before.”

Since then, working with his wife and partner, Grace, Atkins has continually sought to capture such previously undocumented moments in nature. He has shot underwater with 2,200°F molten lava pouring into the sea off Hawaii’s Big Island. (Survival tip: heat rises.) He shot the first film footage of a nautilus, a mollusk that lives 1,000' down in the Indo-Pacific and has evolved very little over the past 500 million years. “You want your films to be unique and to tell new stories,” he says. “Or old stories from a new perspective.

Today is a golden era for wildlife cinematography, with a proliferation of unique films telling new stories — from the singular tale of a burned-out filmmaker who “befriends” an octopus in Netflix’s documentary feature My Octopus Teacher, to an extended series on matriarchal species (such as hyenas, elephants and chimpanzees) shot entirely by female cinematographers for National Geographic’s Queens.

“There is a voracious demand for new content,” says Atkins, who grew up in Mobile, Ala., and studied marine biology before taking up a camera in the 1980s. “When I started, there were very few people in the genre.”

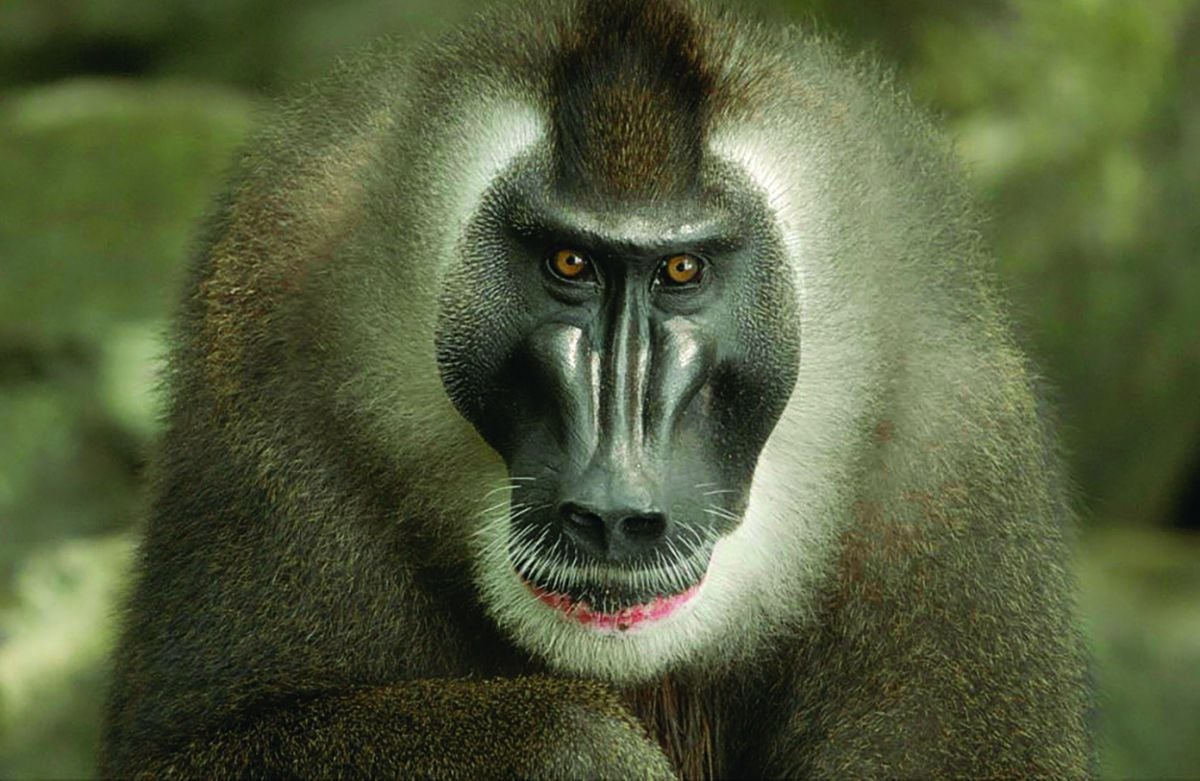

And the films were patchy at best. “Forty years ago, it was enough to just show what animals looked like,” says Mark Linfield, co-founder of Wildstar Films and a former BBC natural-history producer. “You would say, ‘There’s a mandrill!’ It relied on revelation. Today, you need to use cinematography to tell stories.”

“You want your films to be unique and to tell new stories — or old stories from a new perspective.”

In tandem with the demand, there is a growing body of talented — and gradually diversifying — wildlife cinematographers around the world. Their knowledge of animals, their camera and lighting skills, and their ability to shoot sequences that can tell stories are showcasing nature on a cinematic scale, and audiences cannot get enough of it.

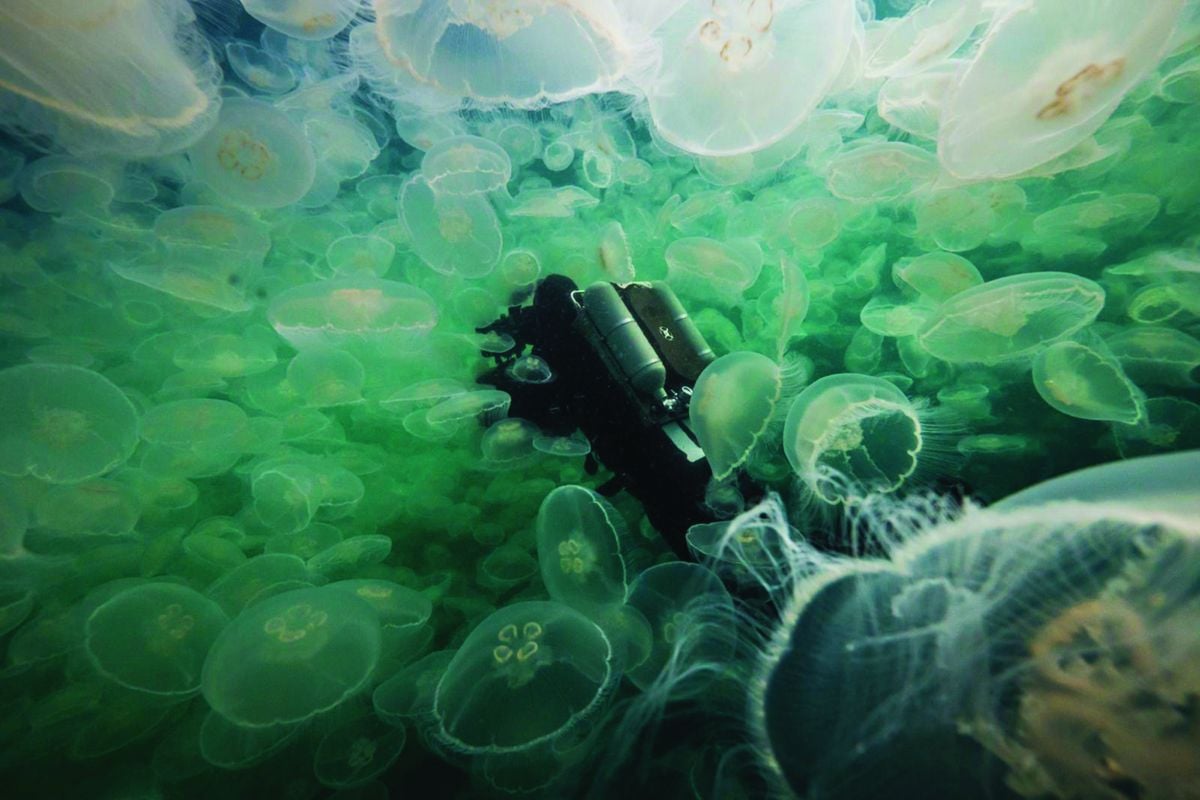

“There is more work than before — more work than there are camera operators to do it!” says San Diego-based Jeff Hester (The Mating Game, Ultimate Rush), whose specialties include underwater cinematography. Historically the industry has been slow to embrace diversity — however, with mentorship programs for diverse voices from around the world now being promoted by nature-film enterprises such as the Wildscreen Festival and Jackson Wild, the hiring of women and people from less privileged backgrounds is starting to improve.

The expansion of the industry is being powered by an increase in financing and distribution networks, as the traditional commissioners of nature films — the BBC, Discovery Channel, and National Geographic — are being joined by streamers Amazon, Apple TV Plus, Disney Plus, and Netflix.

Wildlife cinematographers are also enjoying new technology that enables them to shoot in places and in ways that were not possible before. Rugged, high-resolution cameras with a pre-record function that can capture sudden action shots at high frame rates and with the ability to shoot in low light are now widely available. Red cameras are ubiquitous, but Arri and Sony cameras are favored by some.

“With the new Red cameras — two hours after sunset, I am still [shooting],” says Dereck Joubert (Okavango: River of Dreams, Eye of the Leopard). “The technology is allowing us to creep further into the night without impacting the wildlife.”

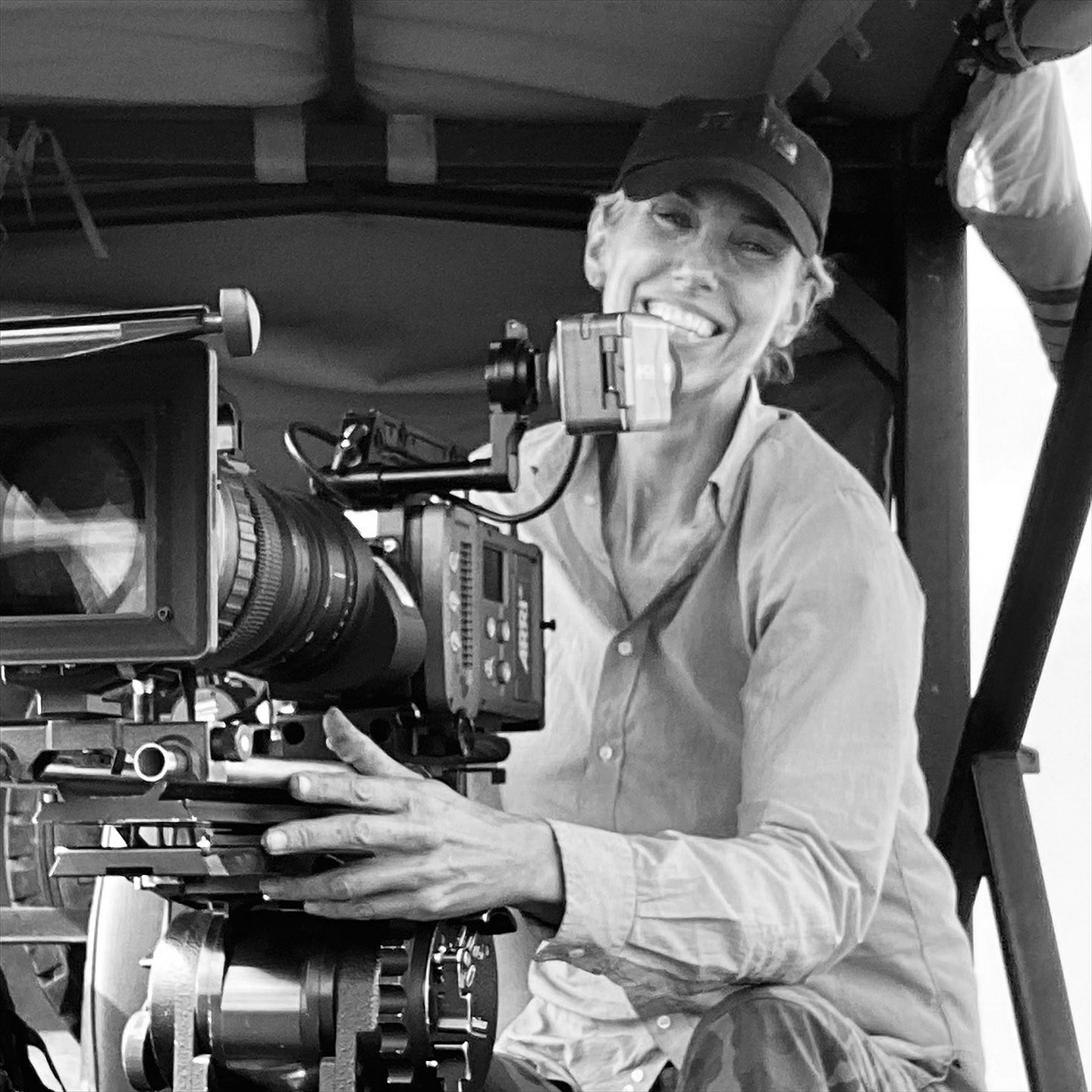

London-based filmmaker Sophie Darlington (Queens, the Dynasties episode “Lion,” African Cats) says, “I started on an Arri. Reds are brilliant, and I am excited about the new Arri [Alexa] 35.”

Almost every wildlife cinematographer will mention using the Canon Cine-Servo 50-1000mm zoom as their default lens. “It was designed for our trade,” says Darlington.

Drones and gimbals that can produce stabilized footage from the air have also transformed how natural-history films can be shot. For some spectacular sequences in the new National Geographic series America the Beautiful, a Red Helium was mounted to the nose of an adapted L-39 Albatros jet that flew long, low passes over the Grand Canyon and Monument Valley, giving a sweeping view of those expansive landscapes.

However helpful new technology can be, “it is the narrative storytelling that makes the difference,” says Silverback Films director Keith Scholey, former head of the BBC’s Natural History Unit. “That is what elevates the top cinematographers and camera operators. They are incredible people — they have to work out what the subject is going to do [10 minutes before the subject does it]. It’s no good knowing 30 seconds ahead because you will miss it.”

Nobody has done more to elevate the art of wildlife filmmaking than the famed Natural History Unit of the BBC. Established in Bristol — in southwest England — in 1957, the NHU pioneered the “blue chip” wildlife series, often featuring David Attenborough’s uniquely enthusiastic narration. “Everybody [in our field] looked to the BBC’s NHU to see how they told their stories,” says Atkins.

The BBC has a rich body of wildlife films, but its 2006 release Planet Earth — an 11-episode, five-year production — has become the reference work for the genre.

Planet Earth was the first major nature documentary to be filmed in high-definition video, and it used cinematography to create a look that hitherto was more typical of feature films. Series producer Alastair Fothergill — also a former head of the BBC NHU — instructed the 40 camera operators who were sent to 200 locations around the world to aim for long, lingering shots. The series included extended sequences of birds-of-paradise doing their colorful mating dances, wolves chasing caribou over the Arctic tundra, Bactrian camels walking slowly atop sand dunes at dawn, and a snow leopard patiently hunting mountain goats on steep, rocky slopes. When the series was done, Fothergill said, “I showed it to the bosses at the BBC, and they said, ‘It is very slow.’ I said, ‘Yes, there are half the number of cuts as normal, but everyone is a Rembrandt!’ I wanted every image to be exquisite.”

The most significant technical innovation deployed on Planet Earth was the Cineflex, a laser-gyrostabilized camera system that allowed stable, long-lens footage of animals to be filmed from helicopters — and could accommodate contemporary compact HD cameras. “You can shoot polar bears with a long lens from the ground,” says Fothergill, who is now a partner in Silverback Films with Scholey, “but you can only understand their lives if you pull out and film the whole expanse of ice and snow, and show how these animals deal with those challenges.”

Wildstar Films’ Linfield adds that the Cineflex could be perceived as the wildlife equivalent of putting a camera on rails or on a Technocrane on a Hollywood set.

Planet Earth was a huge hit around the world, including in the United States, where it was distributed by Discovery Channel. Atkins, who shot several sequences for the series, notes, “Planet Earth came out just as Blu-rays and widescreen televisions were reaching consumers, and it was enormous.” Atkins’ contributions to the show included manta rays at night in Hawaii, and dolphins and sea lions herding schools of fish in Patagonia.

The production won numerous awards, among them Primetime Emmys for Outstanding Cinematography and Outstanding Nonfiction Series, and inspired everyone in the field to push for more cinematic images. “More of my [wildlife] clients have begun quoting feature films as examples of what they want,” says Atkins, who has also shot narrative features himself. “They’ll send me a style sheet with the types of lenses and the depth of field they want. I never got that before!”

Planet Earth has since become a franchise, with a third season slated to debut this year.

As the market has become more sophisticated, producers and directors have become more demanding. “Increasingly, we’re going into the field with storyboards, and it wasn’t that way 20 years ago,” says Roger Horrocks, the South African cinematographer who shot My Octopus Teacher with protagonist Craig Foster. “Our job as a DoP is to serve that story, and that requires coverage skills and the ability to evoke emotion.”

Though some scientists push back on the idea that animals experience emotions — and warn against anthropomorphizing non-human creatures — wildlife filmmakers tend to see it differently. “It is all about eliciting emotion,” says Darlington. “It’s about being able to make people feel emotionally involved with nature. Loads of people stopped eating octopus because of My Octopus Teacher, even though the film doesn’t ever say anything about that. Beauty is the sharpest tool in the box.”

Sometimes it is also the most poignant. Joubert and his wife, Beverly, who have lived in Botswana’s Okavango Delta since the 1980s, were following a lioness and her cubs for The Last Lions (2011) when one of the cubs was trampled by a buffalo. The cub’s back was broken, paralyzing his hindquarters. The Jouberts knew the lioness would abandon the cub because he could not possibly survive in the wild.

Dereck recalls, “The question dawned on us, ‘Now what do we do? Drive off? Stay there and cover it? Or use it as an exercise in what I hope will be some of my best cinematography? We understood the cub had a broken back and was going to die. What did I want the audience to come away with? My goodness, that lionesses feel sadness, too! So I put the cub in the background, slightly out of focus, and the lioness in focus. She moans, and then has a very slow blink. At that point, the story was about the mother and the decision she had to make to move on. Using the art of the lens — there [you see] an individual going through great pain. And by the way, that individual is a lioness.”

Wildlife cinematography poses some unique challenges: The talent won’t stand on marks or take direction, couldn’t care less about a script, and sometimes they won’t turn up on set at all. Filming wildlife often means waiting patiently for long periods of time in intense cold, oppressive heat or some other variety of discomfort — just to get a 60-second sequence.

“For me, filming starts with respect for the animals,” says Darlington. “If you want to film animal behavior, you don’t want them to be aware of the camera. There has been a drive toward reality-TV style filming, which, in my mind, is not respectful. I don’t like seeing an animal snarling at a camera because that means you have upset it. It takes real craft to use equipment without interfering with the behavior.”

It also takes some skill to shoot enough footage to build entire sequences. “The best wildlife cinematographers have also been in the cutting room — they know how to build a story,” says Fothergill. “Often you will only get about 70 percent of what you aimed for, so you need to know how to shoot so you will still have enough for a story.

Wildlife cinematographer Erin Ranney (Natural World, Seven Worlds One Planet), who grew up on Alaska’s Bristol Bay, says she has learned to think days ahead. “If you’re trying to catch an animal’s behavior, you will probably have to shoot over multiple days, but you need to make it look like it all happened in five minutes, so you are often shooting the same behavior in multiple lights and multiple weather conditions. For example, when shooting a mother bear fishing for salmon with her cubs, one morning it’s drizzly and overcast, and then you have a morning with glorious sunlight — so you have to start over and build it out so you have created the sequences the editor can cut in whatever conditions they want.”

As the footage has become increasingly spectacular, concern about the natural world has grown ever more urgent. For years, the blue-chip series avoided discussions of environmental threats and climate change for fear of alienating their audience, preferring to show nature in its pristine form with no traces of human activity. But that became increasingly untenable as animals’ habitats shrank, species became endangered or extinct, and climate change was very clearly threatening the planetary ecosystem.

“We have been guilty of ‘chocolate boxing’ nature,” says Darlington “Commissioners didn’t want to screen the conservation themes, but we have to stop pretending that nature is in a great state. I did three shoots this year and came away desperate every time. We are in the midst of a biodiversity and climate crisis, and we have to speak out.”

Tania Escobar, a Mexican cinematographer based in Brazil, says, “Every time you’re out there, you see how rapidly things are changing and how biodiversity is impacted. You see trash everywhere, plastic everywhere. I did a shoot in the Amazon in November, and we saw fires burning everywhere all the time.”

Escobar understands audiences don’t want to be preached at, but she thinks as generations change, young people are becoming more interested in learning about the environment. “By now,” she adds, “you really have to fake it if you want to make everything look pristine!”

Attenborough, the world’s preeminent voice in wildlife filmmaking, made his own “witness statement” in 2020 with the Netflix documentary David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet. He used footage extending across the 70 years of his own career to document the decline in biodiversity and the onslaught of climate change that he has observed. Addressing the camera in a call to action, he exhorted the audience to “rediscover how to live in balance with nature,” and said, “Using your voice is the most powerful way to create lasting change.

With their increasingly evocative work, wildlife cinematographers stand front and center in this critical conversation about our future.

An extended version of this article appears in the September 2022 issue of American Cinematographer.