Dreadful Demons for From Beyond

Creative prop design and makeup effects help propel this surreal horror feature.

This article was originally published in AC, Jan. 1987

The writings of Howard Phillips Lovecraft — those terrifying, half-mad delusions and fever dreams that usually culminate with the dreadful appearance of some multi-tentacled winged demons from “beyond” — have always proved difficult to translate to the screen. Last year, director Stuart Gordon unleashed his cult classic Re-Animator on an unsuspecting public. Now, Gordon has returned to the untapped treasure trove of Lovecraft’s masterworks to create From Beyond. (Both films were photographed by Mac Ahlberg.)

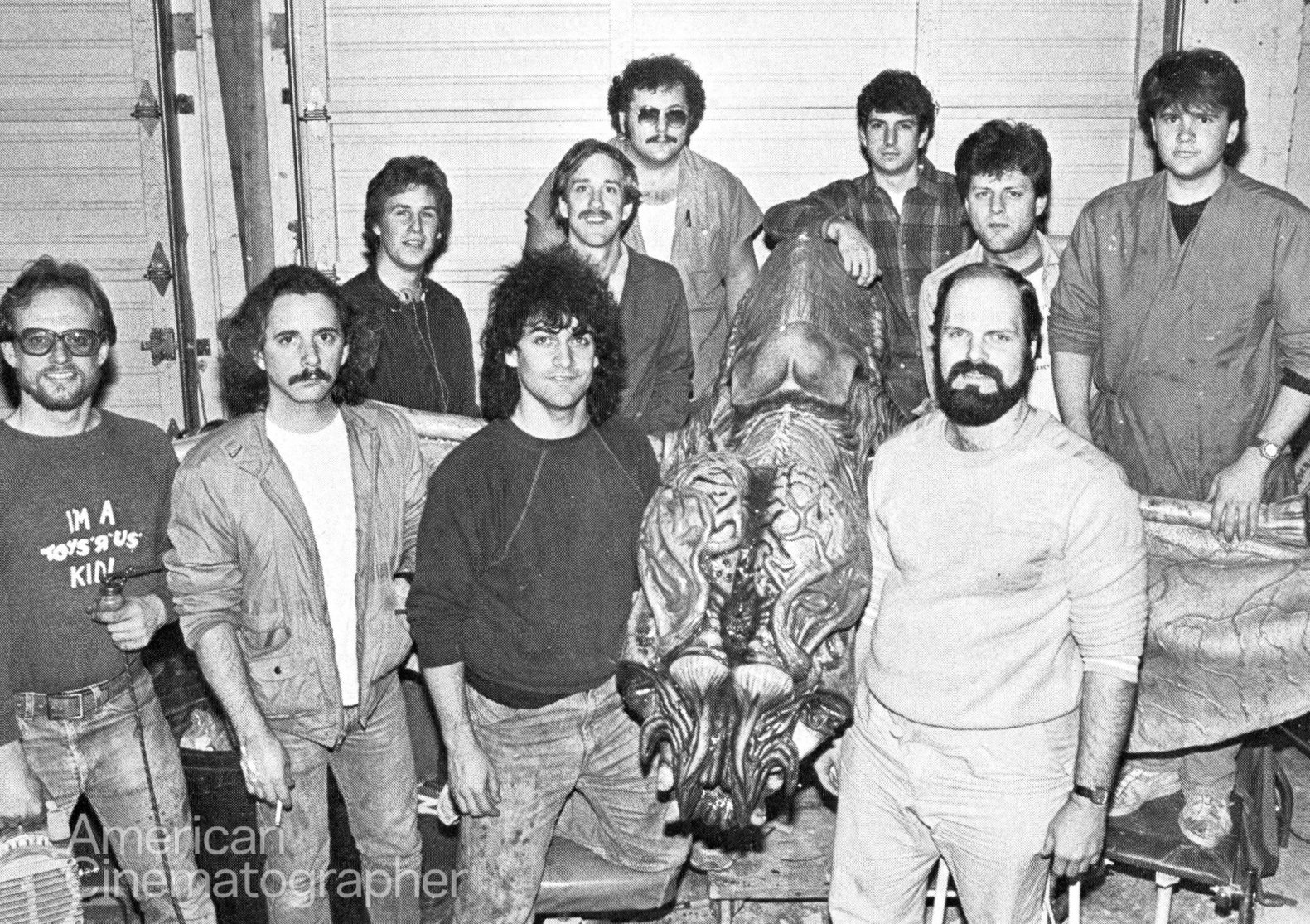

From Beyond is an ambitious attempt to capture the monstrosities and shape-shifters of this remarkable writer’s imagination on film. Four separate crews headed by John Naulin, Tony Doublin, John Buechler and Mark Shostrom combined their talents to produce some startling and original makeup effects.

In From Beyond, as in Re-Animator, Gordon pushes the limits of the horror film genre by portraying monsters who revel in their evil, performing unspeakably perverse acts on anyone unfortunate enough to cross their path. Though such scenes are predestined to fall into a questionable no man’s land between art and taste, the power of Gordon’s imagery is undeniable.

“There’s a definite connection between horror movies and sex,” Gordon believes, “and we felt that we wanted to explore that a little bit more in our film. The character of Dr. Pretorius in From Beyond [an homage to the mad scientist of Bride of Frankenstein] is very much a modern Marquis De Sade and the idea is that once he transforms, he is very pleased with the change, rather than horrified. I like monsters that enjoy being monsters and that’s sort of what I was going for with Dr. Pretorius, who finds he’s able to express himself through his monstrousness.”

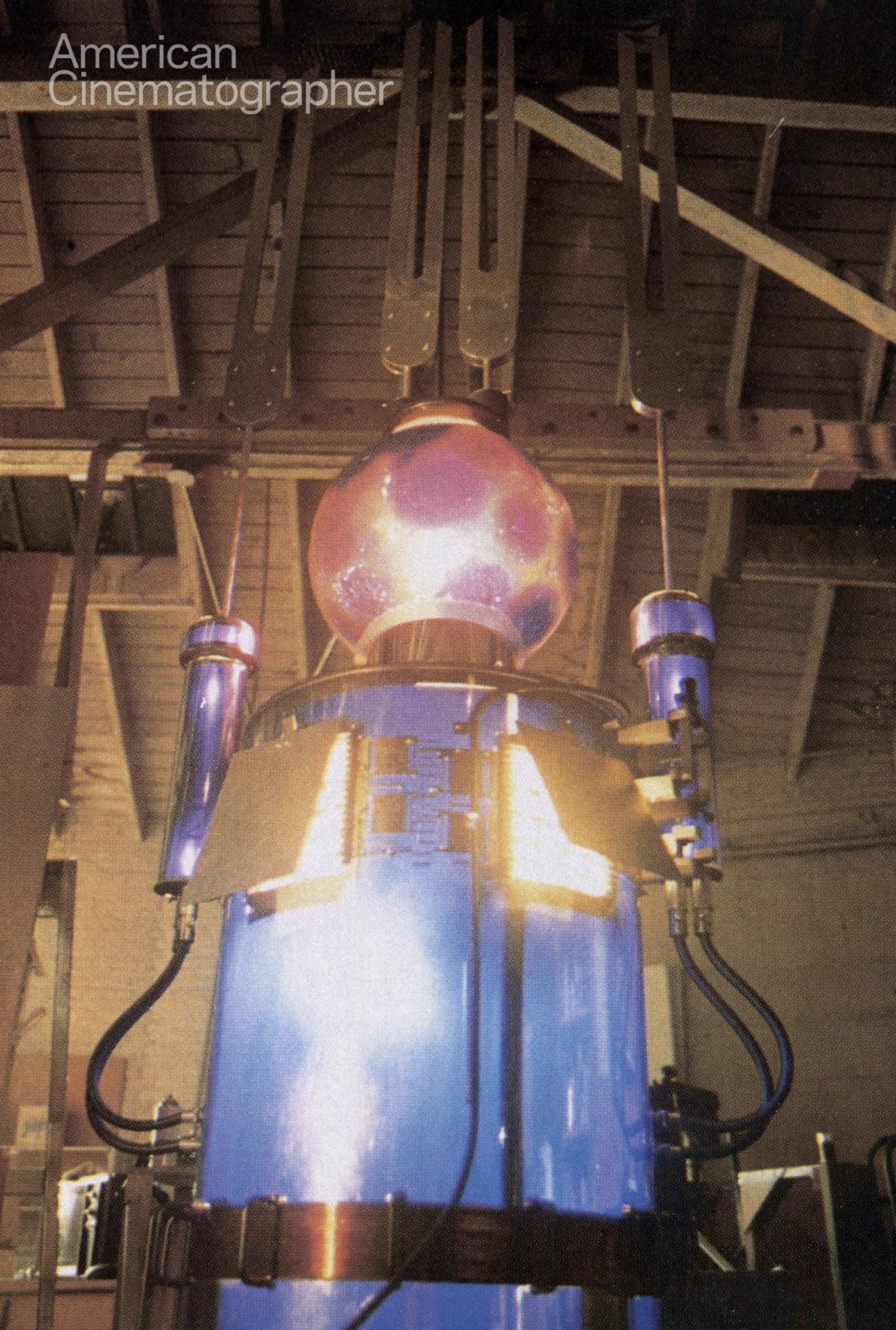

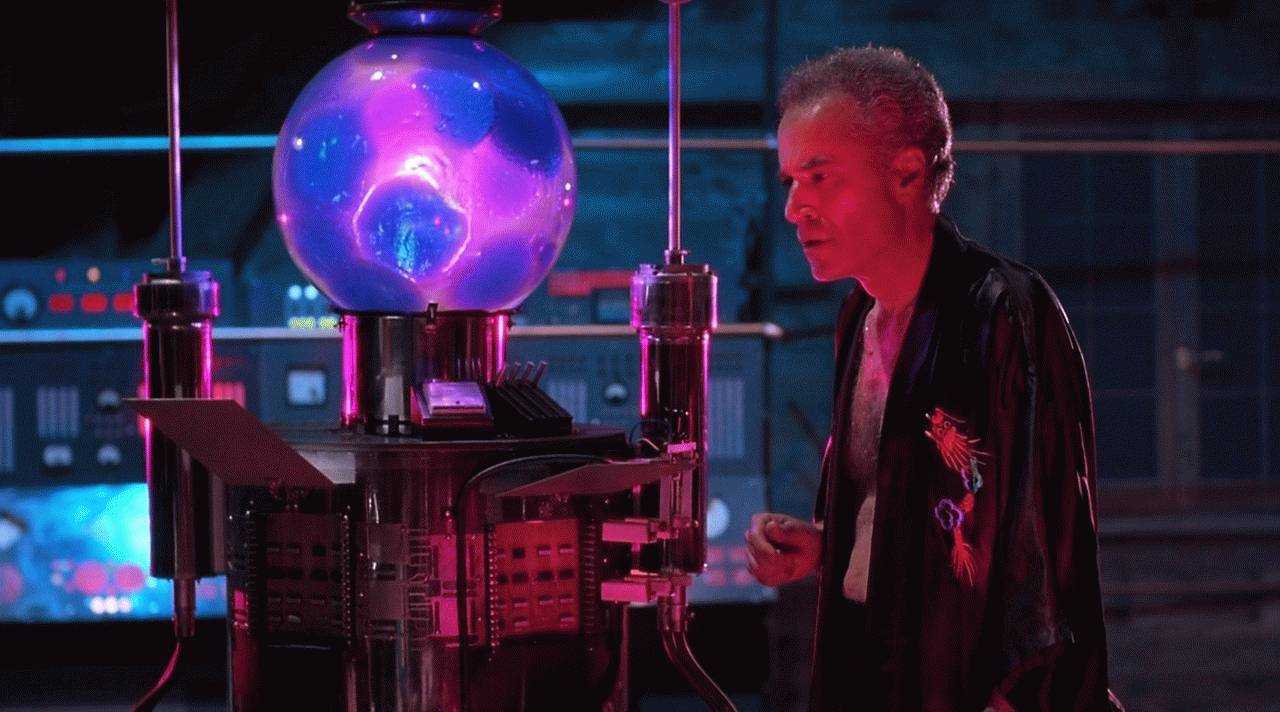

Before Pretorius could actually embark on his journey into the beyond, he required the services of the Resonator, a sinister-looking apparatus designed to stimulate the dormant pineal gland or “third eye.” Although the Resonator is credited to Pretorius in the film, in reality it is the work of 25-year-old David “Zen” Mansley. Mansley’s desire to work on From Beyond stems from a chance screening of Re-Animator. “After I saw Re-Animator, I said, ‘I have to work with Stuart Gordon!’ After that, I got hold of the synopsis of From Beyond and as soon as I read it, I had an idea for the machine. I drew out this cylindrical design, made an appointment with Stuart, and when he saw it he said, ‘This is the best design we’ve got so far. Let’s go with it!’ Stuart liked it because it looked like a human figure with arms and a head and he thought that it was almost like an idol that people might worship. He also thought that it approximated the shape of The Old Ones [dark gods who once ruled our planet] in Lovecraft’s writings.”

Producer Brian Yuzna wanted the Resonator to appear more high-tech, like genuine medical equipment, while Gordon and Mansley wanted to go with a Jules Verne-ish / Kenneth Strickfaden / Universal-horror-movie design. Meanwhile, Mansley continued to refine his original design, visited a physics lab, and conducted an interview with a friend, Doug Westmoreland, who worked as a physicist for TRW. “We recorded our conversation on tape, I gave the tape to Stuart and Brian, and a lot of good things came out of it. When the physicist saw my designs, he was stunned by how accurate they were as far as how it would actually look. From that point, Westmoreland and I developed the theories about how the Resonator works, and once I threw all my research at Brian, he could not refute it, so he said, ‘Well, this is good enough, let’s go for it!’”

Once Mansley’s design was accepted, he now had to build his Resonator, in such a way that it could be broken down for transport to Italy, where From Beyond was scheduled to shoot. Mansley’s Resonator ultimately resembled a water heater gone mad — a huge steel cylinder upon which rested an ultraviolet light ball and from which sprouted four large tuning forks piercing the air like horns. According to Mansley’s physicist friend, the ultraviolet light was visible to the pineal gland, and that, combined with the intense vibrations of the tuning forks, caused the dormant gland to grow, which propelled anyone within the Resonator’s range into the beyond. Be cause Gordon wanted the Resonator’s body to glow from within, Mansley decided to have it, along with the tuning forks, made from clear plexiglass. Then came the task of covering a five foot long plastic barrel with sheets of clear Mylar to give it a high-gloss metallic finish which became translucent when light was projected from inside.

Once the body was completed, Mansley spent weeks combing surplus stores for thousands of dollars worth of electronic switches, lights and circuit boards. But the most difficult part of the entire enterprise turned out to be the construction of the ultraviolet light ball that sits atop the Resonator body. “I wanted the ball to have a kind of depth to it,” Mansley says, “I wanted to be able to see the filament inside it and I wanted the filament to appear to warp as we dollied around the Resonator. The ball had to be made in two halves. I filled it with resin which is an awful process. As I was holding this ball, sloshing the resin in it, with the hole at the top, all of the fumes were going up my nose, so I was on the verge of passing out! I took turns working at both John Naulin’s and Tony Doublin’s facilities, and they’ll remember me crawling out the door saying, ‘I’m passing out from the fumes!’ I actually needed to recover each time I did a resin slosh inside the ball!

Meanwhile, Doublin and Naulin were busily experimenting with a jury-rigged front projection system and a variety of strange eel and jellyfish type puppets in an attempt to handle some creature effects on stage rather than through the use of opticals. Though Naulin was in charge of all non-Pretorius related makeup and creature effects, and Doublin was the physical and floor effects supervisor, they found themselves working side-by-side on many occasions.

Because Gordon had been a theatrical director prior to working on Re-Animator and From Beyond, the idea of dealing with opticals and other elements that could not be handled physically on the set was, at first, intimidating to him. Consequently, Doublin devised a low-budget front projection system. He recalls, “We went through a period of testing during pre-production in order to determine how we could do those effects practically.

“First, we started out with some elaborate test puppets, built by John Naulin, and we tried things like shooting them on wires on the set using high-speed photography. Then we thought, ‘Why not just try floating them in an aquarium?’ So instead of shooting through the aquarium, which would’ve goofed up the whole shot since the camera would have detected the water, we went back to the ’30’s Topper-type effects, using a beam-splitter mirror to actually reflect the jellyfish and eels from the aquarium off to either side at a right angle to the camera. It worked basically like a front-projection system, so we were able to create these effects on the set. We also came up with a way of lowering a matte into the aquarium so we could make it appear as if these creatures had moved behind a static item like the Resonator or a desk. Once we got that to work, Stuart began to feel more comfortable about going with optical effects. We realized that each new set-up required a new set of mattes, and we’d have to bring the aquarium in, get the mirror aligned and then set up the camera before we could do the shot. We did about 14 shots like that, but it was determined when we got to Italy that we’d wait and see what was needed when we got back to the States, and that we’d be better off to do it with rotoscoping.”

Of the smaller creatures Naulin and John Criswell built, the most complex were various eels constructed in different scales for use either in opticals or on the set. What made them particularly difficult to make was the fact that they had to be translucent and yet have a variety of radio-controlled, cable-controlled and air bladder movements, all of which are difficult enough to hide inside an opaque effects piece. Naulin’s eels came in three sizes: quarter scale, half scale and full scale. The quarter scale eel was used only in the aquarium shots, and had no mechanical articulation to speak of, but swam naturally in the tank. The half scale model had some articulation, the full scale model, which measured 29" long, was fully articulated. “It’s got a radio controlled mouth, it breathes, and it could move in three directions,” notes Naulin proudly. “It’s full of subtleties you never saw. It is completely transparent, so you see the veins. Its skeleton was handmade out of plastic rib sections that were linked together by a cable down the center, and it’s got cable pulls on either side that are disguised as part of the veining; so it can move left, right and down. There is a rubber vein structure and rubber air bladders on the inside, and it is covered with a translucent prophylactic skin. It is a completely constructed piece, and when it’s backlit in the film, you can see all the way through.”

Naulin and his crew, consisting of his wife, Shayna, Criswell and Greg Johnson, also constructed an enormous lamprey eel which served as a sentry to protect the Resonator’s power supply (a fusebox located in the basement of The Pretorius Foundation). The finished eel measured 24 feet long, and was partially operated by Criswell. It became so heavy, due to the fact that it was half-submerged in water, that it had to be suspended on wires in order to achieve certain movements. This caused some difficulty because the extreme lighting in the Beyond sequences tended to make hiding the wires a tricky business. This was particularly true of the segment in which Jeffrey Combs as Crawford Tillinghast, Pretorius’ naïve assistant, is nearly devoured by the gigantic creature. “You don’t really see it pull him out of the water,” Naulin explains. “You see him flailing about, nine feet in the air, and, at that point, it’s a stuntman in a full harness that Doublin and the stunt coordinator rigged up. It was all done full size. There is only one quick shot where it appears as a miniature.”

Once Tillingast is removed from the eel’s belly, he is completely hairless. It was at this point that actor Jeffrey Combs’ problems began, for Naulin had devised a bald-cap prosthetic, as well as other facial appliances, to complete his symbolic regression in the film. “The design was inspired by something that Stuart and I had talked about, which was that Crawford is a total innocent, things keep happening to him that he doesn’t ask for, and he has to reach a certain point before the hero can be brought out in him,” Naulin says. “What this makeup does is take him back to an infant stage. I’ve got to say something for Jeffrey: he was incredible with regard to the makeup. First of all, it required full head and shoulder casting, which he’s never had done before and which was an ordeal for him. Then, as I recall, he went into this makeup in some form 23 times. One way or another, the poor guy was wearing bald-caps and eyebrow blocking appliances, foam latex cheek pieces, not to mention all the wounds and bandages and pineal gland pieces — it just got to be more and more!”

“There was an air line that went over the top of his head, emerged from the appliances and hooked up to an air pump so we could make his forehead bulge as if the pineal were trying to push out!”

The effect of the pineal gland enlarging and pushing its way through Crawford’s skull and skin proved to be the most difficult effect Naulin had to contend with. In addition to building some six different mechanical heads to solve some of the problems, Gordon demanded that Naulin develop a method by which the gland could be made to emerge through the prosthetic forehead piece worn by Combs. “They wanted to be able to shoot Jeffrey with and without the pineal, without having to redo his entire makeup each time, which was almost an impossibility since the pineal operates underneath the makeup. We not only had to be able to do that effect, we also had to be able to take it off, shorten the pineal, put it back in or put in air-bladder versions of the pineal — it all had to be like a Tinkertoy set that was interchangeable on set! We solved this problem by having a junction box machined and attached to a band flexible on the inside but rigid on the outside, and that band was velcroed over Jeffrey’s bald-cap before the final foam forehead piece went on. From the back of the band, we ran cables to a joystick control so that the off-camera operator could make the pineal move at his discretion. The whole pineal apparatus could then be removed from the front using Allen wrenches, and the little metal piece had a fitting in it so we could insert the air bladders. There was an air line that went over the top of his head, emerged from the appliances and hooked up to an air pump so we could make his forehead bulge as if the pineal were trying to push out!”

In general, Doublin’s contributions to From Beyond were extremely important, but difficult to describe. Besides handling all the film’s physical effects — which included water pouring downstairs, the rigging of harnesses and the pumping of thousands of gallons of methylcellulose slime — Doublin also supervised the work of Naulin and Buechler’s crews to insure that the effects were done on a timely basis, and then he made sure workshops were set up before the crews arrived in Italy. “My other primary job,” Doublin says, “was to make sure that what was supposed to happen happened. If we had a problem, if they wanted a specific action that was unplanned, I had to figure out a way to rig it or fudge it so at least we could get something that was usable. I could always fall back ten yards and punt! There were a few items that were actually cobbled together as we walked out on the set, or there’d be a change, or the set was built a little differently than they’d planned — but that’s all part of it. You get into it and even though you’ve made all these great plans four months ahead of time, you walk onto the set for the first time and things always change!”

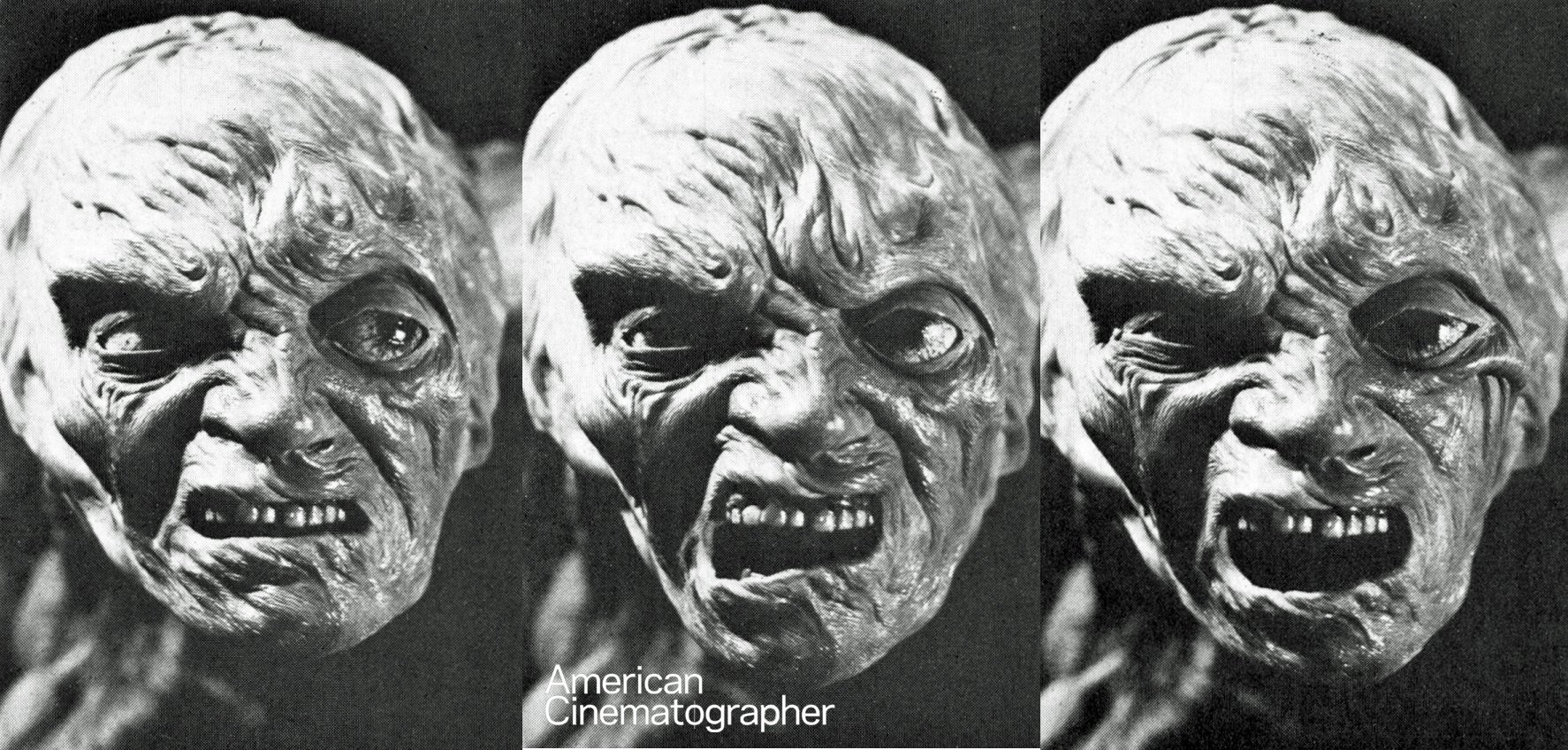

The first Pretorius transformation was handled by Buechler’s team, which consisted of Bill Butler, Joe Dolinich, Tom Floutz, Bruce Barlow, Gabe Bartalos, Bill Forsche, Mitch DeVane, Gino Cragnale, John Volich, Ralph Miller III and Mike Deak. Buechler required the services of each to pull off this remarkable effect, which begins with Ted Sorel (Pretorius) removing the skin from his face to reveal the musculature underneath, which starts to unlace into long tentacles of muscle tissue. “We did something to create that effect that I don’t think anyone has ever done before,” Buechler says. “We combined a mechanism directly inside a prosthetic, so it was very simple to apply. It had a cable-controlled series of units that caused the muscles of the face to retract on themselves. The whole idea was that the muscles had to appear to be unlacing themselves from the skull, so for the next step in the transformation, we cut away to the actors and then back to Pretorius, who was now an animatronic figure which started to elongate and stretch as the muscles continued to unlace and then flail madly about. After we cut to [actor] Ken Foree’s reaction, we pull back and reveal a side shot of Pretorius with the muscles appearing almost like tentacles.

“We used compressed air to make the tentacles appear to move wildly about. It’s all very simple, but you get the feeling that the muscles have come apart.”

Prosthetics and mechanical effects are common tools of the makeup artist’s craft these days, but Buechler developed a system that yields results heretofore only attainable with expensive stop-motion effects miniatures or elaborate full-size mechanical creatures. “I wanted to utilize what has been stop-motion animation techniques where oversized props interact with miniatures,” Buechler explains. “We did just about the same thing, only we used cable-controlled miniatures in place of stop-motion puppets, and we built full-sized mechanicals that had only limited movements and intercut them together. We were able to shoot the majority of the cable-controlled miniatures live on set, and that gave us an advantage over most of the stop-motion effects you see, in that Stuart was able to direct them.”

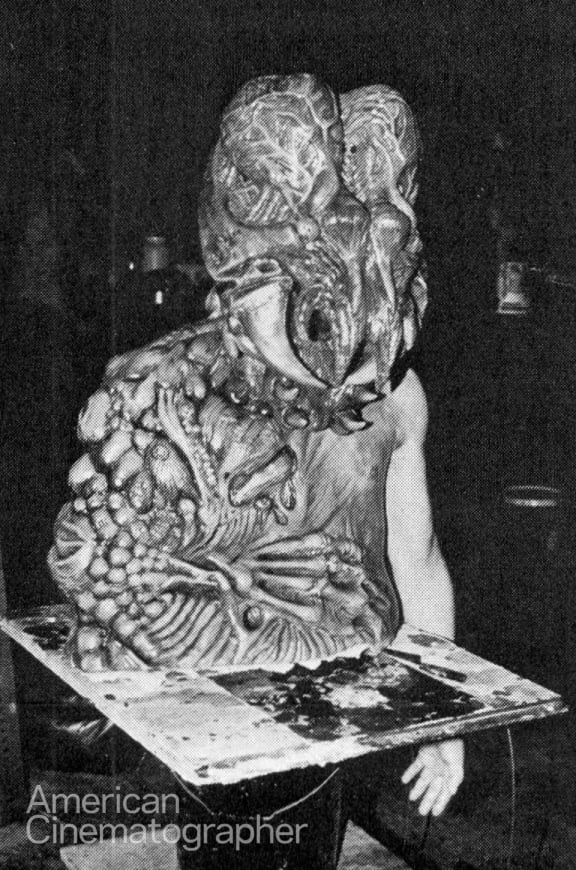

Pretorius’ ultimate transformation begins with a unique creation by Mark Shostrom that almost defies description. The creature is about one-and-a-half times the size of a man, has one human arm and leg — and that’s where all resemblance to any living organism ends. The left side of its body features one long, spindly leg (somewhat insect-like) and a long, muscular arm that ends in a deformed, three fingered hand. A huge stalk-like protrusion atop its shoulders ends in a perverted and malformed likeness of Pretorius’ face.

The creature required more than a 1,000 pounds of clay to sculpt. “The really tough part was trying to figure out how to foam the skin up,” Shostrom recalls. “The skin only had to be about an inch thick, but we had this totally convoluted surface that had to be filled up. I talked to some people who worked at Stan Winston’s shop on Invaders From Mars, and I found out that they’d invented this technology of making things out of polyurethane foam that sets in about three minutes. Their advantage was that those large Martian drone suits were basically round, while our creature was like foaming up some odd tree stump!

“Shannon Shay had to devise this thing called the ‘octoinjection’ system, which took a day to set up and required several people to run the jiffy mixers full of foam. We needed other people to blow compressed air into the molds as we were injecting the foam, which was setting up as we were doing this! It really got pretty wild, and it’s toxic as hell. Afterwards, we had to step on the suit for quite awhile to squeeze out all of the cyanide fumes. Once we got the technology sorted out, then Dave Kindlon spent the next three-and-a-half months devising all of the mechanical parts. It really became a heckuva project for Dave.”

Kindlon’s problems began with Shostrom’s offbeat design. “I designed it with the idea of getting away from the man-in-a-suit concept,” Shostrom elaborates. “In this case, we had a person lying on his stomach on a fulcrum — which is kind of like a see-saw — and the creature was designed around that. The operator’s left arm had an arm-extension in order to manipulate the monster’s big left arm. His head was tucked inside the monster’s shoulders and his right arm operated the head and neck of the creature. The platform the operator was on allowed the creature to move up and down and forward and back. The advantage to working that way is that you can see underneath the entire creature even though its weight is supported by the platform. The idea is that you can see right behind it, you can see underneath it, so it looks like it’s supporting its own weight when, in fact, it’s all mechanical. It’s a combination of almost every trick in the book!”

One of the most successful of Shostrom’s “tricks” was to give all of this strange creature’s appendages movement — something one doesn’t expect to see in a low-budget film, and which really made the monster come alive. Also, Kindlon designed the mechanics for three different heads of Pretorius that attached to the monster’s neck, so the creature appeared to be metamorphosing even further from cut to cut.

Because this particular phase of the Pretorius transformation was composed of more dialogue exchanges than any other, Shostrom devised a way that Sorel’s head could be spliced onto the body of the monster for closeups in which he had to speak. Sorel was made up using appliances that conformed closely to the various mechanical heads, his neck and shoulders were draped with black fabric, and the shot was framed very tightly.

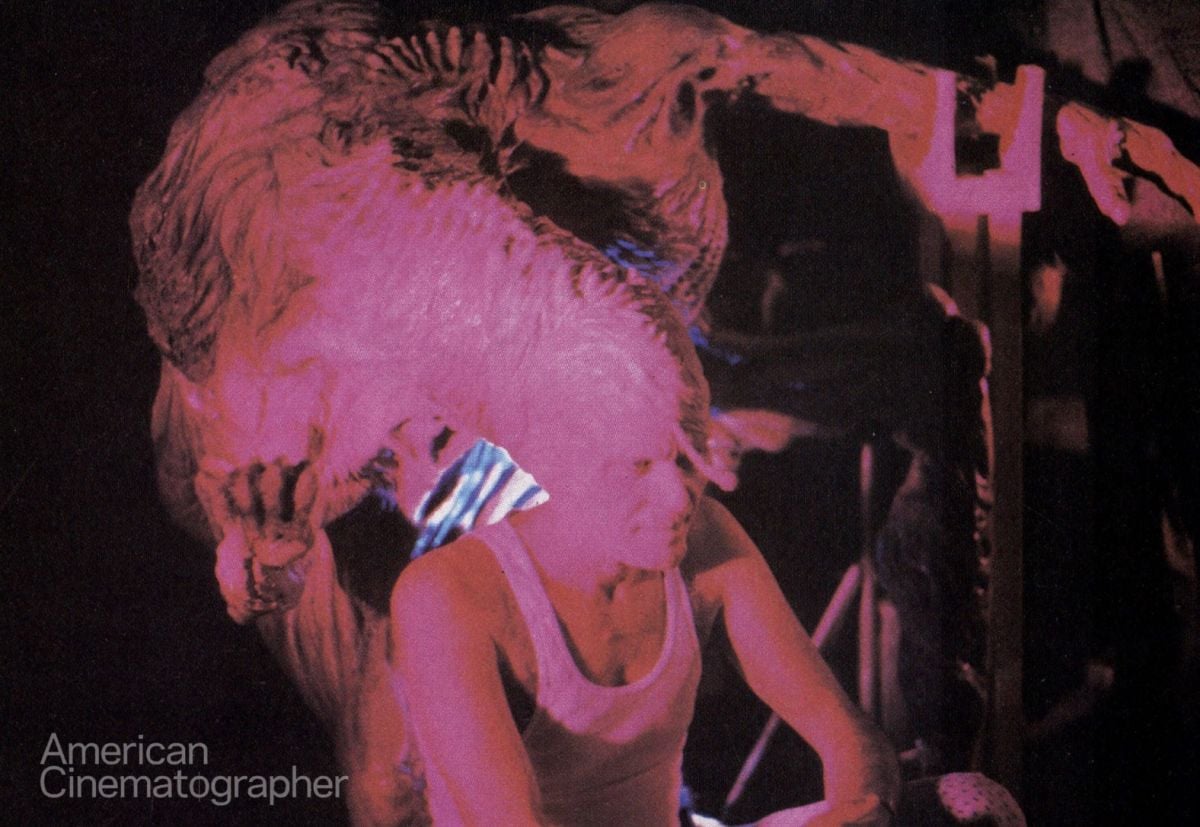

For Pretorius’ final transfiguration Buechler and his crew removed the last vestigial traces of humanity from the perverted form so, using yet another fully articulated miniature, he was able to bridge the gap between Shostrom’s monster and his own. “I did a sort of transition from this wonderful tendril creature to some shrimp-headed brain-thing. It was very strange looking, and it was a combination of a miniature and a full-scale creature. The full-sized monster had an eighteen-foot wingspan, bat wings and shrimp-type scales covering its back. We used the miniature of Mark’s creature. The back of it starts to bulge out and the wings of our creature start to emerge.

We cut to Crawford as he says, ‘Oh, my goodness!’ and then there’s this wonderful bluescreen shot of the miniature flying down toward Crawford from the top of the staircase, using its huge wing claws to bat him down. The full-sized version then grabs him, ‘chows down’ on his head, and then twists it off. Any time you see the two of them together, it’s the full-scale model, but for any of the intercut scenes between Crawford’s point of view and the creature, we used the miniature. The miniature contained a fully articulated cable-controlled mechanism that is capable of simulating flight, all the pincers worked, the brain pulsated and the jaw moved. And that,” he smiles, “is all I had to do with From Beyond!”

Mark Shostrom, echoing the sentiments of all the artists involved, says, “We were all enthused. Even though we were working with a pretty limited budget, we had a chance to really do something that we wanted to do, so we put in a lot more than 100 percent.”

John Buechler adds: “I think you can attribute that basically to the camaraderie Stuart brings to a production. Nobody’s the star, everybody works for the good of the project and I think that in itself is what makes his pictures outstanding. He makes the technician and the artist feel at ease, he works with the talents each person has and he coordinates everybody. That experience and that attitude helped us to work together. We had to on a picture like this: it had a short shooting schedule and some of the most ambitious effects ever in a motion picture.”

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.