Dual Nature: Shadow

Zhao Xiaoding, ASC, CNSC helps bring the visual language of Chinese ink-brush painting to the action and intimacy of this stylish drama.

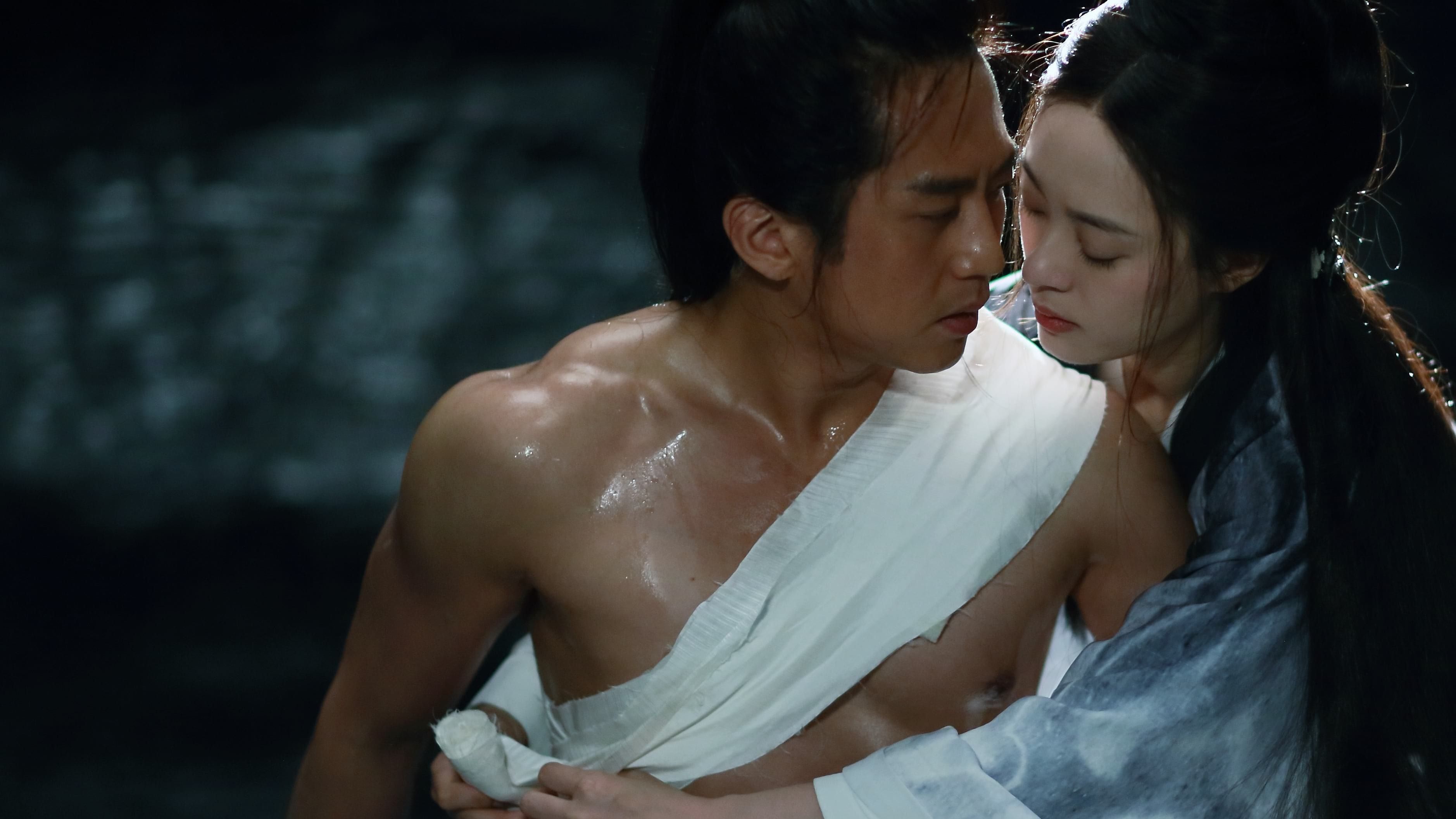

Unit photography by Xiaoyan Bai. All images courtesy of Perfect Village

The Chinese epic Shadow tells a spectacular yet historically based tale of a great second-century general whose kingdom’s future is imperiled when he is wounded and must recuperate rather than fight. He employs a double to pose as him in both public and private life, and goes into hiding to plot his next move. The thematic implications of the general’s story — centering on duality, contrasts and shadow selves — are brought to vivid life by cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding, ASC, CNSC and director Zhang Yimou, who have been working together since Zhao was a camera operator on Zhang’s film Hero (AC Sept. 2003). Zhao was promoted to director of photography on Zhang’s House of Flying Daggers (AC Jan. ’05), and since then they have teamed on visually sumptuous spectacles like Curse of the Golden Flower and The Great Wall. Zhao also recently directed his first feature, Once Upon a Time (2017).

Shadow is perhaps the most stunning product of their collaboration yet, a combination of sweeping action and intimate character study that brings the visual language of Chinese ink-brush painting to cinematic life. AC spoke with Zhao by phone about the project, which screened just a few weeks later at the Camerimage Film Festival.

American Cinematographer: You and Zhang are frequent collaborators. How would you describe your relationship?

Zhao Xiaoding, ASC, CNSC: Our relationship has now spanned 10 movies, and we’re about to start our 11th. Zhang is more than a collaborator; I think of him as a mentor. He graduated from Beijing Film Academy about seven years before me and is 12 years older, and he started as a cinematographer, so we have a common language, although we did have to learn each other’s approach and had a lot of disagreements early on. He started as my teacher and then became a colleague and ultimately a friend. I’ve watched him evolve into a more accessible filmmaker. Hero was a milestone not only for the Chinese film industry but also for Zhang, who had directed only intimate social dramas before that. Hero was important because it showed that Chinese filmmakers could make a big commercial movie for a broad audience. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon was popular, too, of course, but it was not filmed in mainland China by a mainland Chinese director. When we came together, Zhang really needed to change his game and become more commercial, with a greater emphasis on action, and I wanted to go in that direction as well.

Has your relationship with him — and with directors in general — changed now that you’ve directed a feature?

The experience of directing really changed my thought process and made me better understand the ways in which the director needs the cinematography to tell the story. I think it has made me more helpful because I’m not only focused on how to get the best angle, the best lighting and the best camera move; I’m also focused on how the technique helps inform the overall needs of the story and actors.

What did you and Zhang discuss in your initial conversations about Shadow?

When he first approached me, there was an existing script based on a Chinese historical event, but it quickly became clear that this was not going to be a conventional historical film. In adapting the material, Zhang said he wanted to create a motion-picture version of a Chinese ink-brush painting; he had always wanted to get that feeling into a movie but hadn’t yet done it. We had a lot of creative freedom, partly because we were liberated from historical accuracy — ultimately, the names of the characters and the underlying events were all changed. Zhang wanted to make the film very Chinese in tone and color. After trying a lot of different things with color palettes in preproduction, we finally broke through and arrived at a much more extreme expression of Chinese classical aesthetics than I initially expected. Chinese traditional landscape painting was our most important reference. As you may know, it uses a form of perspective that is very different from European painting — it’s not a feeling of close and far so much as large and small. People appear very small based on the vastness of the landscape, and the mountains wash away into nothingness as they go farther and farther back. That’s what we were trying to get at.

“The intention was to make the camera moves we used majestic and Shakespearean. We were going for a kind of gravitas in the story and performances, and limited, intentional camera movement enabled that.”

Were there other visual references?

There was a great Hong Kong director named King Hu who did classic wuxia, and we were definitely thinking of him. And, of course, Kurosawa. The overall feeling of Shadow does reflect Zhang’s love for Kurosawa’s work. Also, before we started shooting, Zhang was in L.A. and saw a special screening of Mad Max: Fury Road [AC June ‘15], which had not played in China. Something about the way George Miller created a completely unique and stylized world inspired Zhang; he was thrilled that a director of Miller’s age could do something so unlike anything he or anyone else had done before, and he responded strongly to the unified, organic vision of the movie — the way the cinematography, production design, costumes, editing and performances all worked together. He said, ‘If we could accomplish that on Shadow, I would be very happy.’ It’s actually very unusual when working on a Chinese movie to be so clear about everything you aim to achieve in every discipline, but that’s what we wanted.

How did the choice of camera and lenses help you achieve your goals?

We were shooting 5K with the Red Weapon Helium 8K and Arri/Zeiss Master Primes, lenses that gave me the sharp contrast I wanted. One reason we chose the Red Weapon is because it’s relatively lightweight, and we were shooting a lot of action where we needed something we could rig together quickly and move easily. We shot 5K instead of 8K because it better facilitated the slow-motion work we wanted to do, and it was easier on the DIT department in terms of storage. We were often shooting with three cameras, which was challenging but necessary; it not only gave us the most material, but also maintained consistency in the performances once Zhang got to the editing room. The emotional through-lines and continuity of the performances were essential to maintain, especially in the fast-paced and complicated action scenes. We used up to four cameras for some of those sequences, which had to be very carefully thought out in terms of which lenses were most effective for each individual moment. Sometimes wide lenses were best, and sometimes we’d want to ‘compress’ things with a long lens to give the shot maximum impact. All of this was discussed with both Zhang and Dee Dee [action director Huen Chiu Ku] for each action scene.

Another challenge was that lead actor Deng Chao played two roles. How did you deal with that?

That’s a good question because it wasn’t handled the way it has been in similar projects. For example, Legend [AC Nov. ‘15] and Gemini Man [AC Nov. ‘19] rely very heavily on CGI, but in our film — and this affected the very DNA of the production — we shot everything twice, with the actor giving a full-body, full-facial performance as each of the two characters he played. We used very little CGI on his performance and no face replacement.

We first shot him in his stronger, healthier version, as the [general’s] double — and in scenes where he’s in the room with the ailing general, we had a body double for the general so the actor had someone to react to. Then the actor left the shoot for five weeks, lost 40 pounds, and came back [to play] the ailing general, and we shot all the scenes again. So we were shooting the same movie twice, the same scene on the same set, but they were separated by three months, and I had to get the lighting to match what it was the first time we shot it. And the set might have changed a little in that time — fabrics might have faded a bit, or maybe there was more dust in the air — so replicating the details of the original footage was a huge challenge. But we did that because Zhang wanted full performances from the actor in both roles and didn’t want to take any shortcuts, so I had to coordinate with our visual-effects supervisor, Samson Wong, to figure out how to do what we needed both on set and for the final compositing. We essentially invented a technology to map what we were filming in the monitor and create sensor points that were visible on set for moments when the characters would make contact to ensure the action would match. Getting that right was the result of a very close collaboration between me, Zhang, Samson Wong and the actors. But you would be surprised to know how little visual-effects work there is in the film; it’s mostly fine-tuning to make things match as closely as possible.

The action sequences in Shadow are complicated but clear and elegant. What was the philosophy behind those set pieces and the camera moves?

We took a relatively restrained approach. In fact, at one point we talked about using a completely static camera, but the producer convinced us that we would end up with too esoteric an art film if we went that far. The intention was to make the camera moves we used majestic and Shakespearean. We were going for a kind of gravitas in the story and performances, and limited, intentional camera movement enabled that. As far as the action goes, there’s a great Chinese action director named Huen Chiu Ku — we call him Dee Dee — whom Zhang called upon to help create a new style of action for this movie. We wanted something different from the typical wuxia film, where people are floating in the air and running on rooftops. That’s great, but people have seen it over and over again. While there are a few action elements in Shadow that might seem a little bit impossible, for the most part our thinking was to make the action as convincing and direct as possible: sword on sword and flesh on flesh. We didn’t think of it as a fantasy movie. With the weapons, Zhang made choices that reflected the theme of the movie, which in a way is about ‘the soft’ conquering ‘the hard,’ yin, the feminine, overcoming yang, the masculine, and water being more powerful than anything else.

What was your goal with the final color grading, and where did you do that work?

We did it in Beijing with [colorist] Qu Siyi [employing Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve]. The idea was to maintain consistency in terms of the overall color palette and to make sure every color was commensurate with the artistic vision dictated by the model of Chinese painting, but also ensure that it was not a black-and-white movie. We wanted human color in it, even though in terms of skin tones, we wanted everyone a little pale, not robust. The color is very subtle even in outdoor scenes; in scenes where there is green in the landscape, it’s a greenish-gray. At the end of the day, it was all about finding and maintaining the level of reality Zhang wanted from the very beginning.

TECH SPECS

2.39:1

Digital Capture

Red Weapon Helium 8K

Arri/Zeiss Master Prime