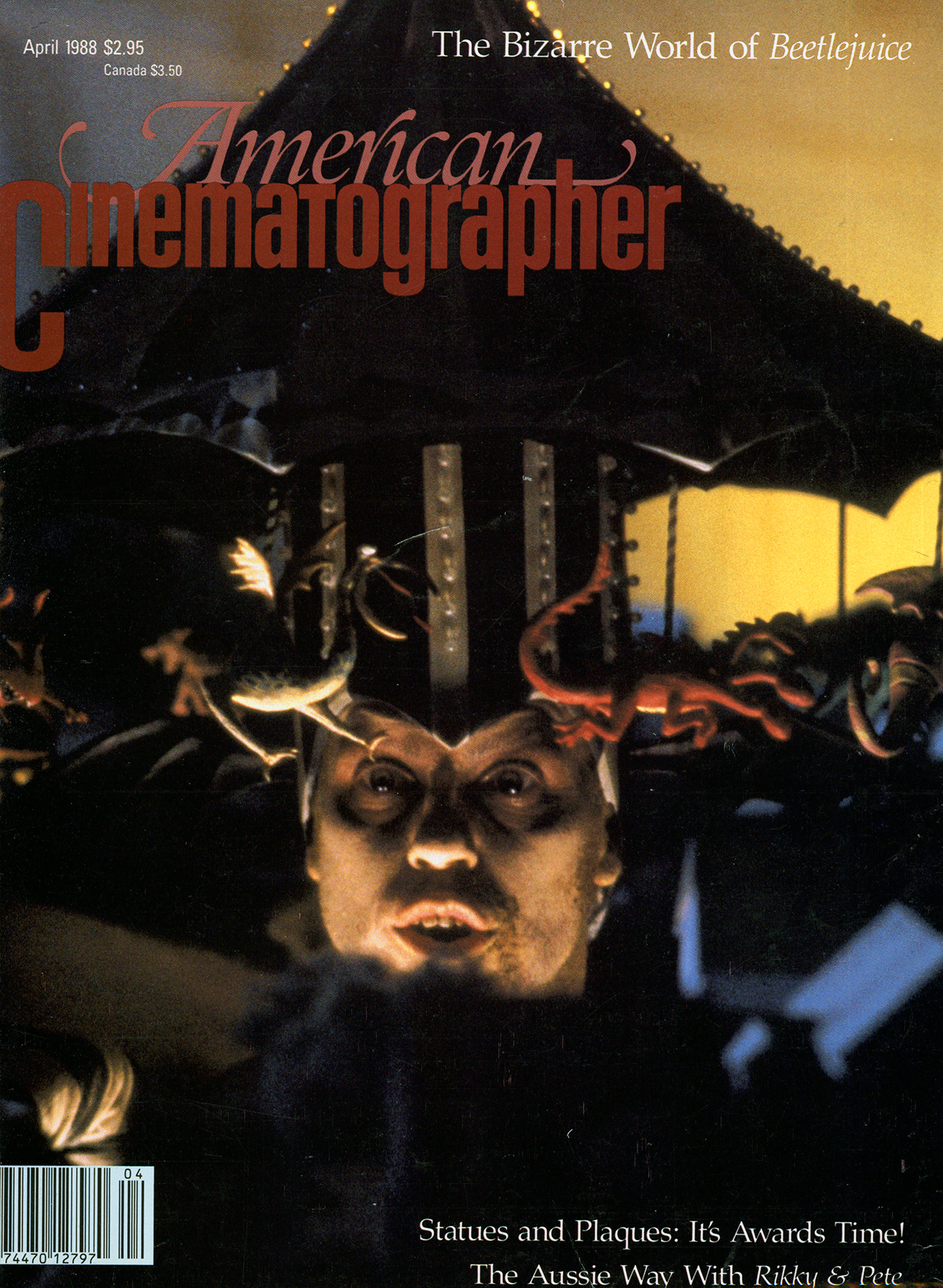

Eccentric Is the Word for Beetlejuice

Shooting director Tim Burton's comedic tale of ghosts and the afterlife was a creative challenge for cinematographer Thomas E. Ackerman.

“It is the same quirky film that I read in the script and it has been rendered as such, which I think is a bold stroke,” cinematographer Thomas E. Ackerman enthused. “Movies should be done that way. A movie has to know what it is from the ‘get-go’ and the director — in our case, Tim Burton — has to steer it so that it is the movie that it started out to be. To try to change horses in mid-stream is usually the kiss of death. It’s important to accept the movie for what it is.”

The movie in question is Beetlejuice, to which the often misused term “different” can be applied without apology. Ackerman, as director of photography, was quick to realize that the photographic treatment would out of necessity lie outside the mainstream. Ackerman — who began his career shooting commercials in 1973 and has since worked on Back To School, Girls Just Want To Have Fun, Road House ‘66, and Burton’s 1984 short film Frankenweenie — is energetic, youthful, and takes his work seriously.

“There are things that seemed fairly bizarre when I first read the script and they remain so,” Ackerman said. “After you have worked on a film for awhile you lose all your objectivity unless it is something very genre or very predictable. Going in, I knew it was going to pose some interesting challenges and it never disappointed me in that regard.

“It’s not a horror film, but certainly has some comedic overtones. It’s a fable — a ghost story, in fact — yet there’s some very funny stuff in it. It has a lot of wit and great irony, with characters that are very strongly etched, but it’s not a slice of life by any means.”

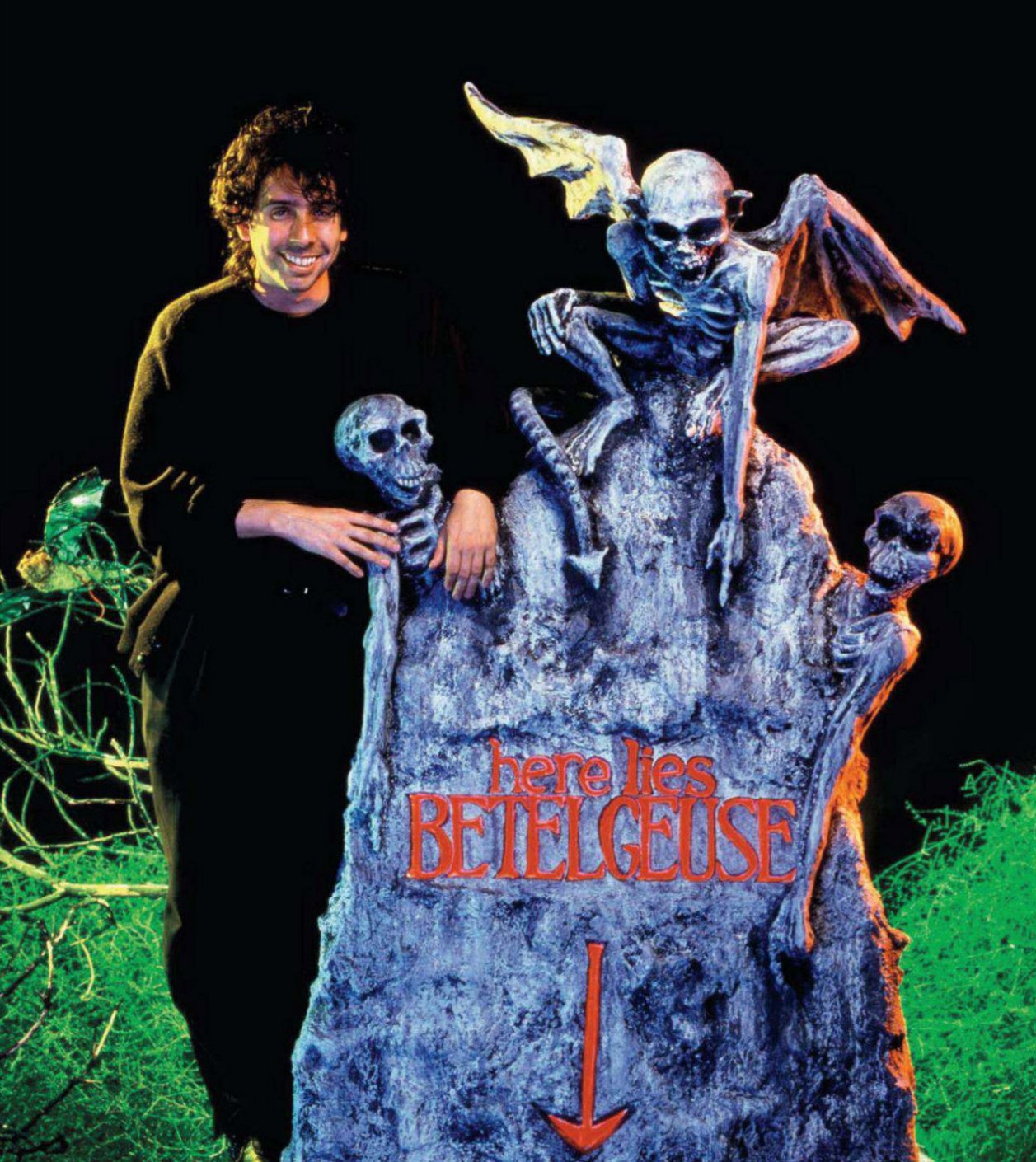

The story tells of Adam and Barbara Maitland (Alec Baldwin and Geena Davis), a young married couple who lead a quiet existence in their comfortable, rambling Victorian home in Winter River, Connecticut. Actually, they haunt the place, having passed over into the afterlife. Enter Charles and Delia Deetz (Jeffrey Jones and Catherine O’Hara), an upscale New York City couple who, with their cool and sullen daughter Lydia (Winona Ryder), decide to move to the country to calm Charles’ jangled nerves. The Deetzs purchase the Maitland home, completely unaware of its present occupants. When they move in, there is a resounding clash of their distinctly urban tastes versus the conservative ideas of the Maitlands as the latter try to save their home from the “artistic” gaucheries of Delia. The ghoulish-looking Betelgeuse (Michael Keaton), who haunts a graveyard in a miniature town that is part of an HO gauge model railroad in the attic, is drawn into the battle with weird-yet-comic results.

Ackerman recalled that he was slated initially for four weeks of pre-production preparation. This stretched to seven weeks because of some casting delays. “It was a good break for me, because of the complexity of the film,” Ackerman noted. “All our stage shooting was done at Culver City Studios, and we did all the location work in Vermont. Of the entire schedule, all but seven days were shot on stage.

“Tim Burton, the director, was adamant that he did not want a ‘shafts of light’ look that by now has been exploited in so many movies dealing with the supernatural. In this case we decided to forego the kind of automatic response this effect signifies.”

Ackerman described the keys to the overall look of the film as “directness, clarity and simplicity. The color palette was deliberately limited and carefully chosen. By and large, we kept the lens free of significant amounts of diffusion or image-altering filtration. I always tend to use some lower-end double fogs to govern contrast. In terms of the lighting, I worked with very bold strokes. Tim was happiest when we were working in a very rich, contrasty manner. In terms of the overall palette of the scenic design, set dressings and wardrobe, black emerged as one of the most important values we had to achieve.”

Some of the strangest scenes occur in a modern visualization of purgatory, as created by production designer Bo Welch, who received an Academy Award for his art direction of The Color Purple and more recently designed the off-beat vampire film The Lost Boys. Ackerman’s description of the setting is eloquent: “If you envision purgatory as being a neverending visit to the Department of Motor Vehicles to renew your license, it gives you some idea of what we were going for! It was not intended to be scary except in unconventional ways. The main set in the afterlife is a vast secretarial pool where the desks go on and on, into the deep background, lost in a sea of computer printout paper and other kind of flotsam. Corpses are shown being being conveyed through the secretarial complex by means of overhead pulley systems. Basically, this is the place where the newly dead go for their assignments to resolve whatever they left unresolved at the time of their demise.

“How does one go about fashioning the look for this kind of thing? Our choice was to make it drab and institutional. The two colors that predominate in this part of the afterlife are a rather sickly green and yellow as seen through a corrugated plastic patio roof. We went for the unappetizing rather than the frightful.”

All the major sets for the picture, except for the afterlife set, are contained in one house. There is a sizeable stairwell where a bannister transforms into a snake. “When the house is cut apart into all its components, none of the parts, except for the stairwell, is very large in scope,” Ackerman described. “In a conventional ghost movie, you think of a story unfolding in a huge country mansion with vaulted ceilings, and vast rooms, but this house was small and, by design, claustrophobic. Actually, it was somewhat more cramped than we would have liked. If it had been just live-action talk scenes that would be one thing, but with mechanical effects and cable work, it becomes quite a Magilla. And I don’t think there was a single square inch that we didn't exploit.

“The house — this character we are talking about — is, in the beginning of the film, everyone’s image of Better Homes and Gardens, a New England country house being lovingly restored by the occupants, a couple so square that the gifts they are exchange are rolls of wallpaper and a can of tung oil. Eventually, it traps them and is sold out from under them to New York sophisticates who proceed to turn it into a kind of a New Age bunker. They gut the place and turn it into a monstrosity about as far as you can get from the Colonial home aesthetic.”

The cinematographer emphasized that bad taste is hard to create. “It had to be credible,” he explained. “You had to believe. It had to be the hippest of the hip, so rapacious and cold that it is almost funny with its perverted images of natural shapes. Bo did a great job walking this line.

“Most of the film takes place in the house. All the scenes filmed in Vermont were exteriors in the village. We also did one day of aerial work using a Wescam mount. This is a gyro-stabilized camera mount which I had never used before. It seemed to me that it did things we always dreamed of doing and hoped could be done when helicopter photography first became practical with Tyler and Continental mounts, which are fine pieces of equipment. The Wescam enables you to operate smoothly at virtually any focal length and allows you to function in a wider variety of weather conditions, such as lumpy air that might otherwise spoil a shot. These introductory shots reveal a quaint New England town nestled in beautiful valley We hovered with a 250mm zoom for a binocular point of view that was as steady as if we had erected scaffolding 1,000 feet high.”

The house itself was not an existing structure but a set constructed for the picture. “They built a three and a half sided shell of the house,” Ackerman recalled. “The house was as much a character in the film as any of the other actors. It was built overlooking the town, a classic case of carrying coals to Newcastle in that we were in this little village — White River Junction. It was perfect in every respect; it looked great. In fact, it has been on many a New England calendar. The only thing missing was a red covered bridge; so Hollywood brought the red covered bridge. In fact, the townsfolk were so enamored of it that they wanted to keep it, but for insurance purposes that was not possible and it had to be torn down. This was the extent of our exteriors. Very little of the film occurs outside.”

Panaflex cameras equipped with Zeiss prime lenses were used throughout. These lenses provided excellent contrast and resolution, according to Ackerman. “Initially, we were shooting all interiors on 5247 [Eastman] in order to ensure the best quality for later optical work. This meant working with heftier light levels than I had used in some time. Fortunately, two weeks into the photography, we switched to Eastman's new 5295 emulsion [ASA 400], which they kindly provided to us in a large quantity as a trade test for their new product. Prior to that it was being used only for special effects.

“We had wanted 5295 to begin with, but since it was only available in limited quantities, we held little hope of getting enough for a feature. I had tested it and thought it was terrific. As luck would have it, Eastman chose two films for the trade tests for general cinematography; one was Tucker and the other was Beetlejuice. Our experience with it was very good. Initially, we planned to do our interiors on 5294, which is a very fine film. However, early on, we decided to do the entire film on 5247 for the reason that if live action would have to be optically sweetened later on, we would need the reliability of 5247. The 5294 emulsion tended not to hold up in all the intermediate steps in the optical process. However, when 5295 became available to us, we were delighted because here we had ASA 400, a very wide latitude, excellent color fidelity, and T-grain emulsion, which makes the acutance of the emulsion almost indistinguishable from 47. Last, but not least, it gives excellent blue/green separation, which makes for very good compositing. It also helped yield rich blacks, which were important to maintain in our film.”

The fact that much of the picture supposedly happens in a tiny HO gauge model railroad town did not pose as much of a problem as might be expected. As Ackerman commented: “Light is light, and it’s a fact that if you were to photograph a miniature you would try to light it in a realistic way, so that there is the ‘reality’ of light. Then there is the light that it absorbs from the room around it, which is much more surreal. Basically, when we are inside the town, we see the facades of the buildings lit as if from an unseen moon — as if there were moonlight streaming into the attic. The only model-like touch might be the fact that if you look carefully you’ll see that the windows of the houses have no details. We just put tracing paper on them and lit them from within. In the cemetery, there was no light source to speak of except for a yellow glow that comes from a rather tacky Betelgeuse retail sign located next to his grave.”

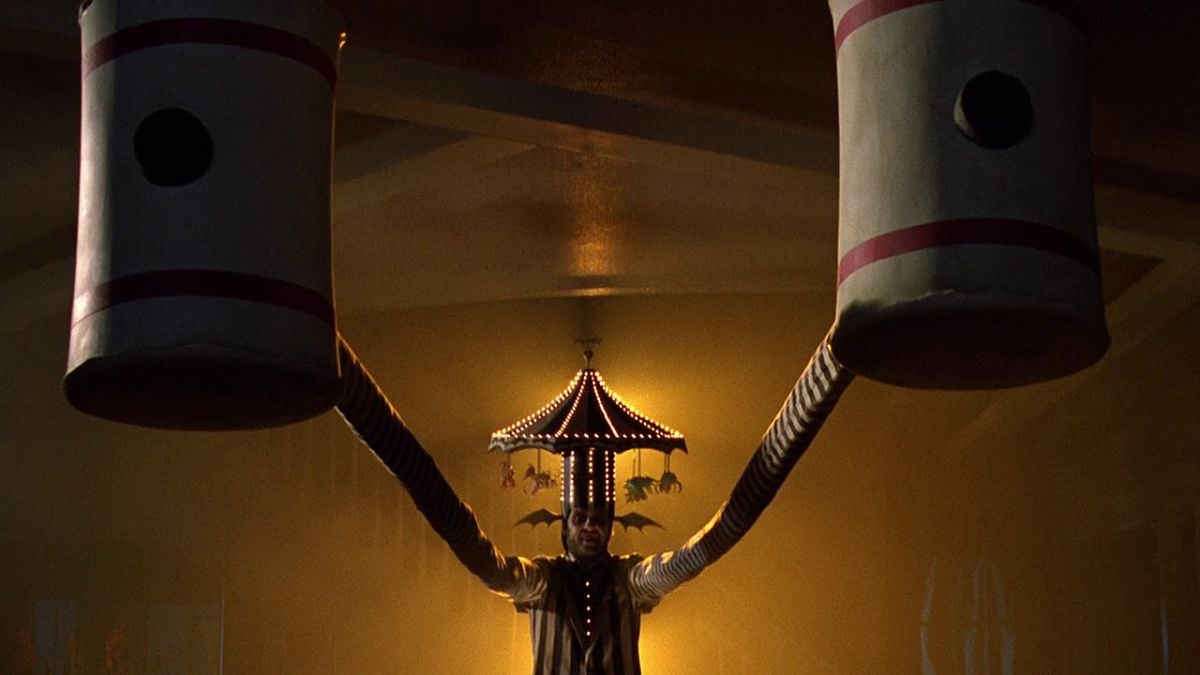

Betelgeuse himself provided some lighting questions in that he is seen in a horrific makeup, yet is not actually a horror character. Extensive tests were done on the makeup, wardrobe and lighting of the character, as played by Michael Keaton. Ackerman described the character as “not completely despicable, but a kind of scoundrel. He wants to come over to the real world and is trying to find his ticket out.” The only way he can achieve this is if a certain incantation is uttered.

“The final patina for his makeup was very pale with just a tinge of green mold here and there, a sort of fright wig look to the hair — Harpo Marx with a zillion volts pumping through — plus an unseemly stubble of beard,” is how Ackerman described his star. “He’s like Miami Vice with a few centuries of mold mixed in. His wardrobe lies somewhere between lounge lizard and Boris Karloff. We shot Beetlejuice much like any other principal appearing in the same scene.

“Most of his scenes are low-key, rather sketchy, stark. There is a matter-of-factness to some of the scenes with Betelgeuse which arises from the way the scenes were written and conceived and put together which suggested that we not go overboard on what I would call classic horror film lighting. In fact, the subtext was not horror but irony. So there were times when we did resort to the ghost movie idiom and borrow from that, but other times we referred to Betelgeuse very matter-of-factly. Here is a guy several centuries old, his pockets bulging with every kind of serpent and cockroach that might co-habit the underground, and he's walking around in your living room — so where do you go with that, visually? Sometimes it's more interesting to play against type, or, in this case, light against type.”

“Betelgeuse is not the only weird character in the movie,” Ackerman adds. “He has a supporting cast of some of the most bizarre characters to hit the silver screen in some time. When I read the script, I found it difficult to conceive of what a scene would look like when you've got two newly deceased people gaining entrance to the afterlife, walking through a fireplace in their attic through an imaginary door to a green void into a waiting room inhabited by other dead people who are not as cosmetic as our regular folks. Many characters are the product of innovative puppetry, such as ‘Char Man,’ who is burnt to a crisp but continues to puff away at his chain-smoking habit, and the former magician’s assistant who sits with one half of her body on one chair and the upper torso on another.”

The village model had to be HO scale because anything larger would not fit in the attic of the house, as the story calls for. There were three life size replications in which the live action was done: the graveyard, the main street and Dante's Inferno.

“On the main street, Bo Welch created some very-fine forced perspective which pretty much dictates where the camera lens must go,” Ackerman revealed. “The production design philosophy in marrying up the full-scale miniature with the reality was that less would have to be more. The budget constraints were such that there had to be limitations on special effects. The graveyard and main street sets were played in limbo instead of using process photography to establish the ‘attic’ background. The thought was to just be bold; do it — maybe not dot every I or cross every T — and render it in a simpler way.

“We tried to make the attic sequences that were integrated in sort of a sketchy way, so that the eye would not be drawn to detail and when you’re in the model you are not begging to see detail.”

The New Wave lighting fixtures throughout the remodeled house were properly eccentric, but could not be utilized as practical sources. Ackerman cited “a piece of sculpture with a little, glowing ping-pong ball on the end of it. It looks great, but as a practical, it was impossible. And we had a black lamp structure against the black leather furniture which could never be used for real light. We had to be clever in how we hid our lamps in order to generate enough lighting for the filming. Sometimes it had to come from an unseen source. We tried to vary the lighting because, since we were working in limited geography, the only way to communicate day or night or mood was with the sculpting of the light. We played a very wide range, working at the murkiest edge to some high key interior looks.”

Ackerman was informed that one of the leading ladies — Winona Ryder — would be always dressed in black. Later, he discovered that her hair was black. Then Burton decided she should wear a broad-brimmed black hat, asking if that would be a problem. “The coup de grace,” as Ackerman recalled, “was ‘Would you mind Lydia in the black dress with the black hair and the broadbrimmed black hat with a black veil?’ I was now a bit nervous; however, it still seemed like a good idea. It is easy for the cinematographer to be come a naysayer and to worry and fret about everything presented to him. We do have an obligation to spell out the pitfalls and liabilities, but, by the same token, I think it is unfair for a cinematographer to come aboard and reject summarily the concepts which have been arrived at by the director and the production designer. There’s a point where legitimate contribution ends and a sort of dictatorship begins. Although I have very strong opinions, I want to get into the aesthetic of the director, to support the director and try to visualize what he has in mind.”

Chuck Gaspar and Joe Day, two of the top experts in the field of mechanical effects, were heavily involved in the production, and Ackerman was delighted with their professionalism: “They had huge challenges but they always delivered and everything worked as promised on the right day at the right time.” An interesting example is a levitation scene, in which the Maitlands comes to the realization that they are dead and have become ghosts. While they sleep in their bedroom, Barbara is floating above the floor when a noise wakes her and the spell is broken, whereupon she crashes to the floor.

“This is live action,” Ackerman explained. “It required that we line up the exact camera angle beforehand in such a way as to have Geena Davis’ body block the apparatus. There was a slot cut through the set and they installed a dog-leg piece of steel rod with a form-fit, contoured body platform that she could rest on comfortably. We had to do very little except choose the ! camera angle and be helpful with the lighting. After the angle was chosen, Joe rigged it and welded it and it worked.

“We did as many in-camera effects as possible, to avoid bluescreen in order to make a nice first-generation neg when feasible. It’s in keeping with the esthetics of simplicity. Some worked out, some did not. There were lots of wire shots, such as the levitation scene, and these required the cooperation of a lot of departments. It helps to have set designed in such a way that a busy background will hide the wires. We could use no backlighting — that shows the wires. The blocking and choreography of the shot are all-important. The good thing about a wire shot is that once it is wired up and operating, you've got the shot and you move on.”

Some mirror shots, which have a very brief screen life, were among the most challenging in-camera effects, according to Ackerman. “Making ghostly images appear using a 50-50 mirror is fairly routine,” he explained. “The subject that is to be superimposed is against a black background and at right angles to the camera, the mirror is at a 45 degree placement and the mirror axis marries up to the camera axis and you get a transparency. It works very well. However, the desire here was to have a solid-looking image, which posed the following problems: There was a two-shot in the film with Adam and Barbara in the attic. A seance is going on down in the dining room which will eventually cause Barbara to disembody and then be reincorporated on the dining room table. We have the couple in the attic, then she fades away. They both have to look absolutely solid, and when she fades all we see is what was behind her. In the usual mirror image you see 50% of the subject and 50% of the background — a ghost.

“In a high-key, well-illuminated scene it would be awfully difficult, but in the attic it was sketchy enough with light-dark patterns that all that was needed behind the Barbara would be a couple of joists with shadows playing across them. I set an individual light on that part of the background that mimicked the surrounding light on other parts of the background. The other lights didn’t strike the area behind the character, but this one special light, which was placed on a dimmer board, did. As all the lamps illuminating the subject mirror image were taken down, the background lamp was brought up, giving the illusion that her solid embodiment was removed, revealing what had been behind her.”

There were other considerations in making the mirror shots, Ackerman noted. “Because of the physical proximity of the couple we had to make all the lighting completely interactive. If Adam has a backlight, it has to hit Barbara, too. If they’re both sitting on the same level, then the axes have to match exactly — they have to be the same distance from the camera and resting at the same angle. She has to have the same key light as him, even though it’s actually a different key light. Backlight, fill and all the molding have to be credible. It’s also necessary to adjust for the discrepancy in the color cast and density of the reflected image versus the transmitted image. I knew we had succeeded when Rob Hummel from Technicolor called one morning and said: ‘We were just looking at dailies and the darnedest thing happened — one of the people disappeared.’ A freedom you have when you do a mirror shot like this is that once all the geometry is worked out, the camera can pan and tilt freely.”

A number of fantastic creatures and puppets were designed and built by Robert Short Productions for live-action photography. “It’s a very painstaking business and these guys don’t have the budget of NASA, so sometimes it takes a lot of ingenuity,” Ackerman noted. “What we saw was pretty much what we got. It all works quite well visually.”

In addition to in-camera effects, a number of bluescreen shots were made during principal photography to be composited later by Peter Kuran. “Bluescreen,” Ackerman said, “is no big deal. Have your gaffer put in lots of light and the right coloring — make sure you have a richly exposed negative and don't make the mistake of putting a lot of diffusion on the lens — and then it is gracefully in the hands of the compositing team. I’ve never done a film with this many effects sprinkled through it. There is some stop-motion animation which was intercut with live action which matches very faithfully. When we have sculptures coming to life and walking across the room and grabbing somebody, it’s a combination of stop-motion animation and mechanical special effects which were fantastic visual sleight of hand. Our desire was not so much to use special effects to create a Star Wars kind of show but to integrate them into an individualistic movie.”

Ackerman was enthusiastic about his Beetlejuice crew. His operator, Doug Knapp, has been with him on other films. “I’ve never been able to design a shot that he couldn’t make,” Ackerman said. David Parrish and Patty Harrison were his assistants, Bill Silic was gaffer and Ted Rhodes was key grip. He is a firm believer in growth and change. “Someone once said to me, more perplexed than critical, ‘Gee, we just looked at some of your commercials and a couple of your pictures and some of these things looked different from the others — we wouldn’t have known that one cameraman had done all these things,’” he mused. “Fact of the matter is that I try to design the images following the concept of the project and different films inspire different approaches to things.

“The only allegiance one can have is to be merciless in making the work the best that it can be. Sometimes it is fun to take on a real toughie, which this one was.”

Ackerman would later become a member of the ASC, and photograph such features as National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation, Jumanji, The Battle of Shaker Heights, Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy, Balls of Fury and Fired Up!

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.