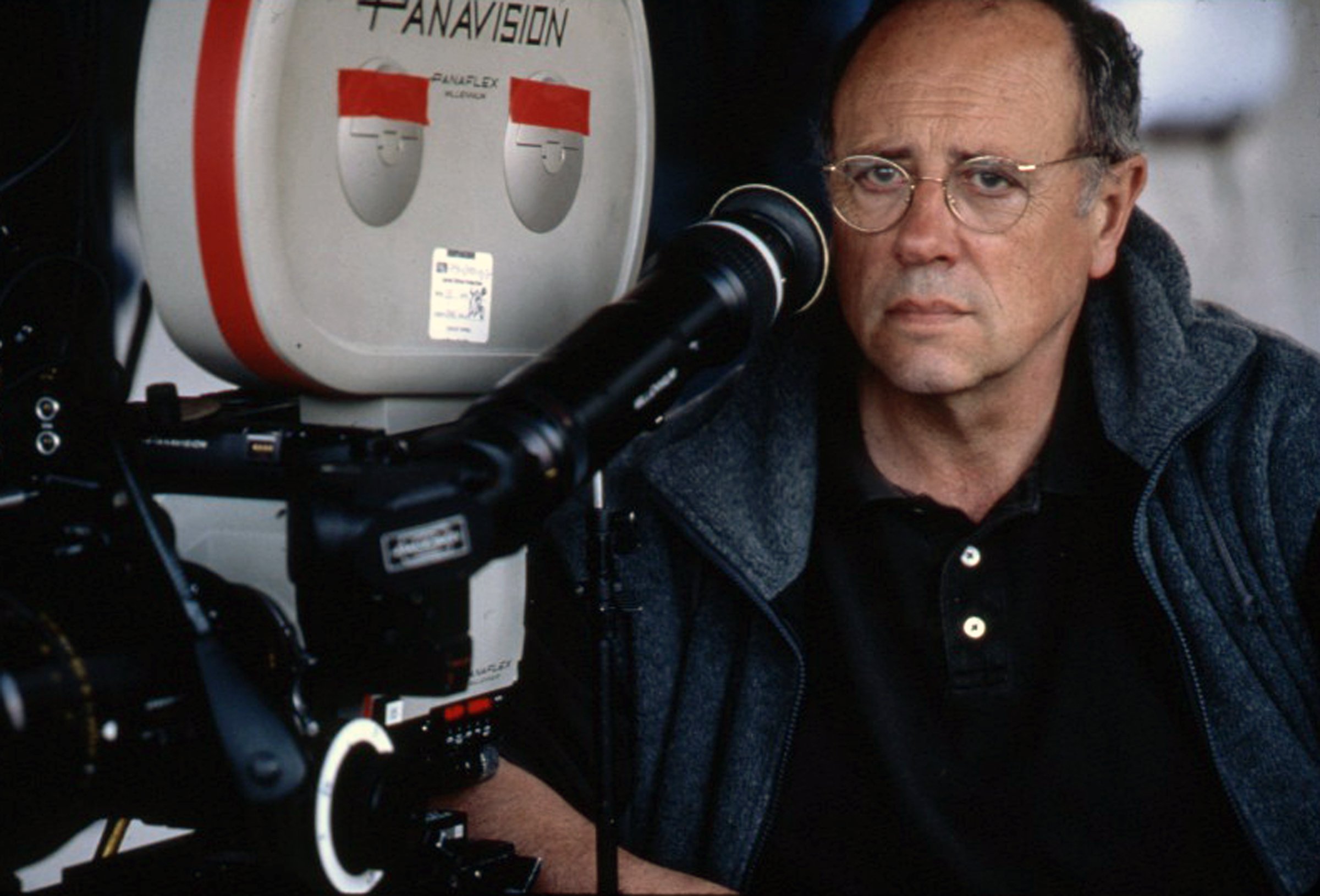

Eduardo Serra Lends his Eye to Unbreakable

The story of an “average guy” who discovers that he’s become indestructible.

Unit photography by Frank Masi, SMPSP

Before serving as director of photography on M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable, Eduardo Serra, AFC had never dealt with the paranormal. True, he had shot What Dreams May Come, “but I don’t really feel as if that film was about the paranormal,” the cinematographer says. “It was more a film about the afterlife.” Of course, Shyamalan’s breakthrough hit The Sixth Sense was definitely a paranormal tale, and his new project also deals with the uncanny. Serra recalls, “When Night first sent me the Unbreakable script, I was in Europe, and The Sixth Sense hadn’t been released there yet, so I really didn’t know anything about him. We had a very interesting conversation over the phone about Unbreakable and his ideas [for the picture]. The key thing he told me in that first conversation — which was very surprising — was that this was a story of a simple man and his family being confronted with some strange events. The family was not just a subplot, it was the key [to the film].

“When I did see The Sixth Sense, one of the things that I found so interesting was [Night's] real care for the characters; he has a real love for people, a genuine kindness. And I think that’s also true of Unbreakable; whatever fantastic adventures happen, the film is first about people, and about the relationship between a man, a wife and a son. We always made the family scenes at home warmer in color tone than the exterior world; even if there are problems [in the home], it’s a warm and good place.” The cinematographer adds that the extra sense of warmth was created with just a hint of CTO on soft light sources.

“In our [initial] meetings, we determined how the color structure depended on the character. Each character would have a color arc, quite a subtle game with changes of colors...”

Serra, whose credits also include The Wings of the Dove (see AC June ’98), Jude, Funny Bones, The Color of Lies and Map of the Human Heart, says he has always been fascinated with the subtle ways in which color can affect an audience, and he worked closely with Shyamalan to design an appropriate color scheme for Unbreakable. “In our [initial] meetings, we determined how the color structure depended on the character,” Serra says. “Each character would have a color arc,’ quite a subtle game with changes of colors — things that are not supposed to be very obvious onscreen, but which still create a feeling [in the audience].”

The two most important “color arcs” belong to the main characters, David Dunne (Bruce Willis) and Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson). Bizarre and mysterious events make David practically invulnerable to injury (hence the film’s title), but his friend, Elijah, is born terribly frail and becomes weaker as the story goes on. Their characters are complementary, and so are the color arcs Serra chose for them. “David goes from cold to warm light,” Serra explains, “and Elijah goes from warm to cold. They are symmetrical reflections of each other, so their color arcs move in opposite directions.” For the most part, Serra achieved this delicate shift with camera filters, but he sometimes used gels on the lights.

At the start of the film, there’s nothing particularly unusual about David’s look. But as his transformation proceeds, his lighting becomes more stylized, as Serra explains. “Sometimes, I used visual references to comic-book style. In fact, our main pictorial reference was comic books.” In the story, Elijah is a huge comic-book fan, and he gains a strange sort of comfort from David’s increasing power. For Elijah, it is evidence of a rational, ordered universe, in which his friend’s invulnerability balances out his own physical decline. By the time the movie ends, David is lit rather harshly, almost like a superhero or “a piece of marble sculpture,” Serra notes. “[His appearance is] more abstract, silhouetted; I was playing with shadows [to convey the impression of physical strength in some shots].” Serra used a single key light from the side to get this sculpted look, usually a Kino Flo or a tungsten Fresnel.

“[Unlike David,] there is no radical change in Elijah, so the [color shift] on Elijah is not as big,” Serra notes. “We see Elijah three or four times before he appears as an adult: at birth, at age 6 and at age 10.1 used coral filters on the camera for Elijah’s childhood, [and as he gets older] he becomes more normal [in color tone and then a bit] cooler. I pull-processed Elijah’s childhood scenes one stop to make them softer. Other than that, I did nothing unusual with the processing. We used two stocks, Kodak Vision 320T 5277 for family scenes and Elijah’s

childhood, and Vision 500T 5279 for the exterior world.”

In one long, handheld shot, Elijah’s mother gives birth to him at a 1950s department store. The scene was filmed at a converted convention center that hid an unexpected bonus in its ceiling: old track lights, just like the kind you’d find in any department store 40 years ago. Serra’s chief lighting technician, Steve Litecky, details, “We used those track lights practically unchanged from the way they were originally installed — incandescent, tungsten practical, 150-watt mushroom bulbs, pointing straight down at racks of clothing and merchandise. Off to one side, we had 5K Skypans diffused by 20-by-20 gridcloths; those units provided general background light for the store, and none of it spilled onto Elijah and his mother.”

Elijah’s mother lies on a small couch with the camera at a low angle, looking across her to the doctor who delivers her son. A white paper Chinese lantern with a 500-watt Photoflood on a dimmer provided soft lighting for these closer shots. “I often use Chinese lanterns,” Serra says, “as big as possible. They are very good for one-light shots. I put them as close as possible to the edge of the frame and sometimes follow the actors around with them.” The mother’s face was lit by a pinpoint of light from high above — a Mole-Richardson Tweenie, Litecky says, “with Lee 250 in front for a little diffusion. That was basically it for the delivery scene.”

Serra prefers a soft texture and usually gets it without using lens filters. “A couple of times, I might have used a very light Tiffen [white] ProMist for some close-ups,” Serra says, “but as a rule, there was no diffusion on the camera.” According to Litecky, the soft light was often generated by Aurasoft lighting fixtures. “You don’t see those all that often, but Eduardo specifically asked for two and used them extensively, particularly on interior sets,” he notes. “They’re great as very soft, one-source lights, and they take either HMI or tungsten halogen globes. The tungsten [about 2900°K] was used for interior soft light, and the HMI [around 5200°K] was used for exterior soft light and also for simulating daylight coming through windows.”

Serra describes Shyamalan as a director who is extremely concerned with emotions, particularly when it comes to motivating camera moves. “If you are supposed to do a tracking shot,” Serra explains, “the cue for the move would never simply be the fact that somebody moves or follows somebody. We moved to reflect or catch a change of emotion.

“For example, there is a scene in a train car where David Dunne is joined by a girl who talks with him — it’s a long shot that lasts maybe four minutes. Instead of cutting from one character to the other, the camera moves and masks one of them. Unbreakable was filmed in anamorphic widescreen [2.35:1], so half the screen is always blocked by one train seat and only one character is visible at a time. Then the camera moves and you see the other actor, according to the lines and emotions. While we were shooting, this all had to be precisely timed; if we missed a moment, we had to start again. It was a subtle movement, no more than two feet from side to side, with the camera mounted on a LennyArm [II Plus], which allowed us to use a normal focal-length lens about three feet from the actors.”

Although the passenger-car set was lit by 65-watt fluorescent overheads running the length of the train, most of the lighting came through the windows. “We used low-angle 10Ks through diffusion as key sources aimed through the windows,” Litecky says. Blondes diffused through 216 frames were at times substituted for the 10Ks and were electronically flickered to produce the effect of passing trains.

Like the department-store set, the backyard of the Dunne home was another practical location, built from scratch at a city park. The yard featured a porch, rear facade, and an in-ground, tarp-covered pool. In one scene, David is thrown into this pool and nearly drowns; Serra originally wanted to light the sequence with a single practical, an exterior backyard light perched under the eaves of the roof. Litecky recalls, “We had a hard architectural light shining down on the pool, but it wasn’t quite right, so we ended up using a Blonde as the source. The fill light was a Tweenie at ground level, diffused through a 4-by-4 216 frame. For some shots where David gets tangled up in the pool cover, an underwater camera was used. It was handheld, and the shot is from beneath him, looking up. You can see the practical on the back of the house, but we supplemented it to bring out the bubbles and movement. We took a couple of Pars and bashed them down at the pool — not to light his face, but just to see the desperate, swirling movement as he tries to escape.”

Serra adds, “That was a very important scene, and we played with just that light [as a source]; it’s very harsh, and it’s interesting what you can see and not see from being just under the water level.

“Another very interesting location was a bank that we transformed into a train station [see lighting diagram below],” the cinematographer continues. “It was a wonderful old building with very high ceilings. Night wanted a nighttime shot that would reveal [the interior] from ceiling to floor, which was quite difficult to light. However, there were holes in the ornamented, cement ceiling [which the bank had used for sodium-vapor lights pointed down at the marble floor], so we replaced the [sodium-vapor lights] with 1.2K tungsten Molepars, which provided much of the light for that scene.”

“The general mood of the train station is very contrasty because it shows a dramatic moment when David makes important decisions. It became one of my favorite [scenes] in the film.”

The Molepars were also pointed straight down and bounced off the white floor, providing soft, generalized fill. Additional smaller lights were bounced into the floor for tighter shots as needed. “We put 10Ks on the upper level,” Litecky adds, “skimming the edges of the pillars. We used two-tube Kino Flos to backlight a Plexiglas wall and two four-tube Kino Flos to light an area near some stairs. A back hallway was lit with 2900°K Kino Flo tubes placed in existing fixtures. In one area that wasn’t lit by the bounced Pars, we used two [4K tungsten] Aurasofts on low stands pointed up at the ceiling to mimic Par light bouncing off the marble floor.”

Serra says this type of lighting was “exactly what Night needed to produce the cathedral-like impression he was after. Also, quite unusually for me, I put in a little smoke, just a little atmosphere, so you feel those lights. That was it — we used very little fill except [on] close-ups, and that would just be a Redhead or Blonde [bounced into 4-by-8 beadboard or off the floor. Bounced 2Ks also were used to light frosted Plexiglas windows along a false wall.] ” If one ofthe ceiling Par beams happened to interfere with a closeup, that particular unit was simply turned off. An old-fashioned clock at one end of the station was lit from the inside by dimmer-controlled 100-watt household bulbs.

“The general mood of the train station is very contrasty because it shows a dramatic moment when David makes important decisions,” Serra notes. “It became one of my favorite [scenes] in the film.”

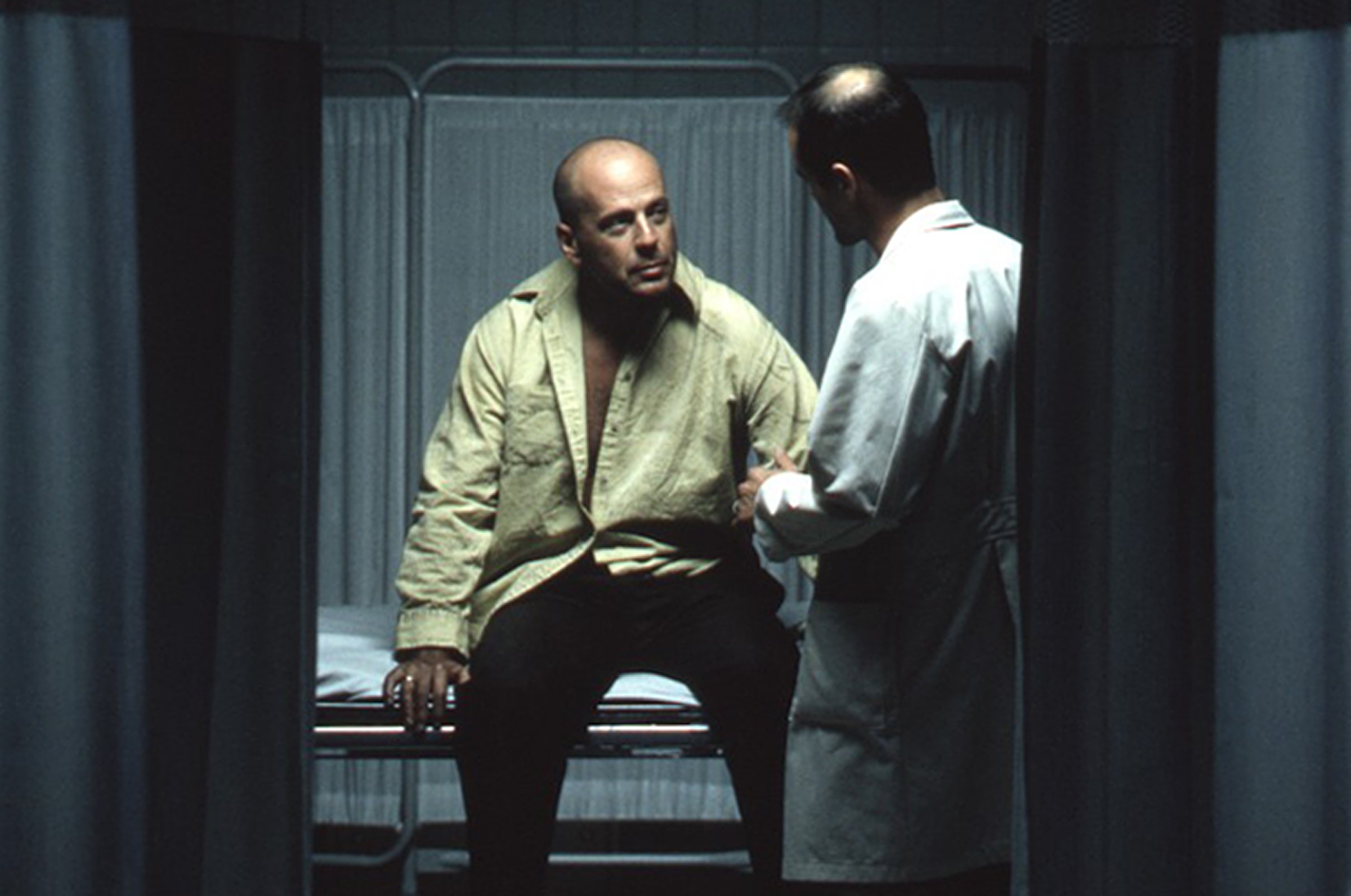

A train crash leads to a significant scene at a hospital, where accident victims are being treated. This was a real emergency room in a real hospital that had recently been shut down. One of the first shots shows a bleeding victim in the foreground and David sitting on a gurney talking to a doctor in the background. “That was very simply lit,” Serra explains. “We just used fluorescents above them for the foreground and the background; there were no reflectors or muslins.” The existing emergency room drop-ceiling lighting consisted of four-tube fluorescent fixtures. The crew replaced the standard tubes with color-corrected Chroma 50s, and one of these corrected four-tube fixtures provided Willis’s key light. The body in the foreground was lit by a four-tube daylight Kino Flo, deployed as a high backlight pointing toward the camera.

The next scene incorporates a 360-degree Steadicam shot as David exits a hospital elevator into a hallway, where he’s met by a flock of reporters. The fluorescent tubes in the elevator were replaced with Chroma 50s, but the crew discovered that the tubes in the hallway ceiling fixtures were non-standard, and that the available color-corrected tubes wouldn’t fit. Instead of replacing the tubes, the crew simply gelled them with Full Minus Green.

Detailing his camera and lens package, Serra offers, “Our lenses on the show were anamorphic Primos and an anamorphic zoom; [we used the zoom] very subtly during other moves on an arm or [while] tracking [instead of for zooms]. We had a Panavision Millennium, a Panaflex G2, and a Panavision Millennium XL, a smaller and very interesting camera that we generally used for crane shots, handheld shots and Steadicam shots. Night was very aware of when to use the Steadicam and when to go handheld; those techniques present two different emotions, so he was very careful [with them].

“I don’t like to have lights all around in every direction. There were times when we managed to do interesting things with basically one light.”

“For instance, there was an important Steadicam sequence, a difficult shot near the end of the film in which David carries his wife up some stairs. The Steadicam moves around them in an incredible ballet, which is intended to create an almost magical feel, as if David’s wife is floating. The actress [Robin Wright Penn] was supported by wires, and the Steadicam operator circled them several times.” Although the scene was filmed on a set, the complicated move made it next to impossible to hide lights. “We couldn’t follow the camera, and we had to watch the wireless video-assist, which isn’t as good as the cable-connected image. It was difficult to judge the lighting, and it was kind of a blind shot, but it turned out very well.”

As David carries his wife, they are lit by a Redhead positioned at the top of the stairs and bounced off a 4- by-4 headboard. When they reach the second-floor hall, the lighting comes from a single Kino Flo pointed down through the false muslin ceiling. “We tried to follow the actors upstairs with a Chinese lantern,” Litecky remembers, “but we eventually decided not to do that. So when you watch the scene, you’ll see almost no additional fill light. It’s very dramatic.”

Serra says he prefers to use the fewest sources possible. “I don’t like to have lights all around in every direction,” he says. “There were times when we managed to do interesting things with basically one light. There’s one scene where David is looking through a closet, and we [lit] him with just the single household bulb that appears in the shot. He’s looking through newspapers, and they bounce the light onto him. I like taking advantage of things like that.”

David experiences visions at certain moments throughout the film, and for one of those scenes, Serra considered lighting the actor from above. “For me, toplight [suggests] film noir, but, for Night, it has a completely different ambience, like low-budget TV,” Serra says. “Instead, to create a sense of drama, we used sidelight — a soft light fitted with an egg crate to make it a bit directional.”

One shot turned out to be considerably more difficult than anyone imagined: a scene from Elijah’s childhood filmed entirely as a reflection in a blank TV screen. Serra says, “That was a nightmare, even after the art department made the screen as reflective as possible — it’s still a TV screen and not a mirror. We lost four or five stops between the real people and their reflections, and we had to pour incredible amounts of light onto those poor actors. In addition, the light had to be bounced [to maintain a soft feel]. We ended up at T11 or T16 on the real actors and T2.8 or T4 for their reflections in the screen. The worst problem of all was keeping the lights out of the shot. It was a very long, hot shot.”

Litecky details, “There were windows on both sides of the TV. We covered the window on the left with 216 and aimed two 6K Pars with medium lenses straight through it to light the front of Elijah’s face. On the right, we bounced three 2.5K HMI Pars into headboard. That gave us just enough light to see the reflections of the actors in the screen. Later, the camera pulls back and we see the people themselves, so a lot of flags had to be used to make sure their backs weren’t as hot as their fronts. That was one long take.”

Another interesting one-shot scene is a handheld sequence that shows the aftermath of a car crash. The shot begins with David picking himself up off the wet street, and the camera tilts up to his face and follows him as he runs towards the wreck. Realizing that his wife is trapped inside the burning car, he wrenches the door open, unfastens her seat belt, takes her in his arms and carries her across the street as the camera is walked backward in front of them. As he sets her down on the road, the camera is lowered with her.

A Chinese lantern on a fishing pole (comprising a 250-watt Photoflood with dimmer controls on the handle of the pole) followed David as he went to the car and worked to free his wife; her face was lit by two full CTO-gelled Tweenies on a flicker generator. The level ofthe Chinese lantern was varied slightly during this shot, depending on the distance to the subject. “The most important light for that scene was provided by firebars,” says Serra, who lit the entire carnival scene in The Wings of the Dove with little more than firebars and torches. “It was shot quite realistically, with no streetlights. There were lights in the background that just barely showed the woods near the road so it wouldn’t look like a stage shot.” This background illumination was provided by 10 1K Molepars, evenly divided between two Condor lifts.

“I must say that working with Night was a fascinating and wonderful experience,” Serra concludes. “He doesn’t work in the traditional, classic American way of shooting a master shot and then doing plenty of closer shots just in case. He doesn’t really do coverage; he has very long, composed shots, and everything is carefully storyboarded. Although we certainly changed [some] things, most of the time we followed the storyboard. His approach combines the best of both worlds: America and Europe. Night has the style and freedom of imagination that European directors are allowed, but at the same time he’s not self-indulgent and is always focused on the audience, which European directors often tend to forget about"

Serra was invited to join the ASC in 2002 and honored with the ASC International Award in 2014.