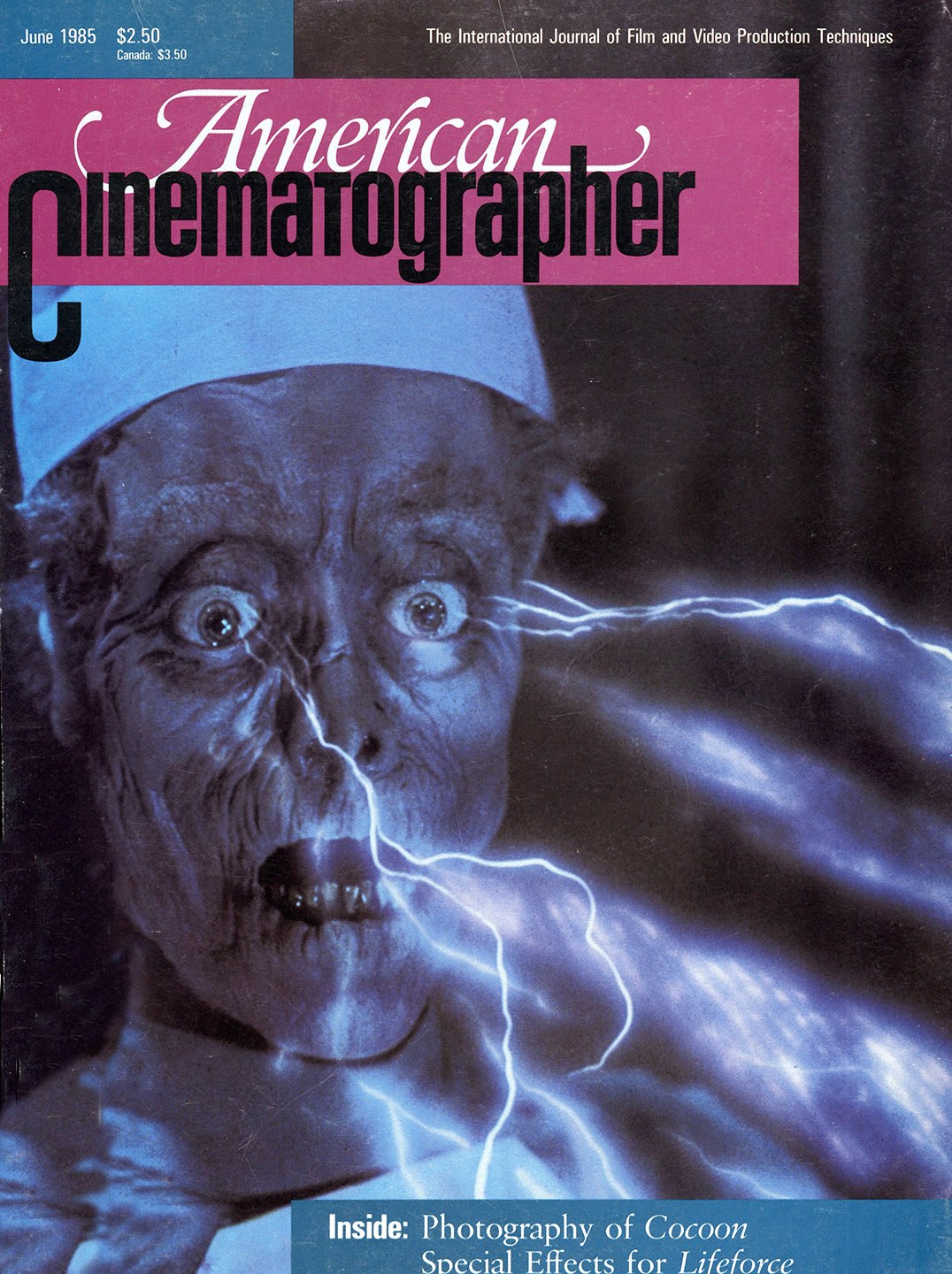

Eerie Effects for Lifeforce

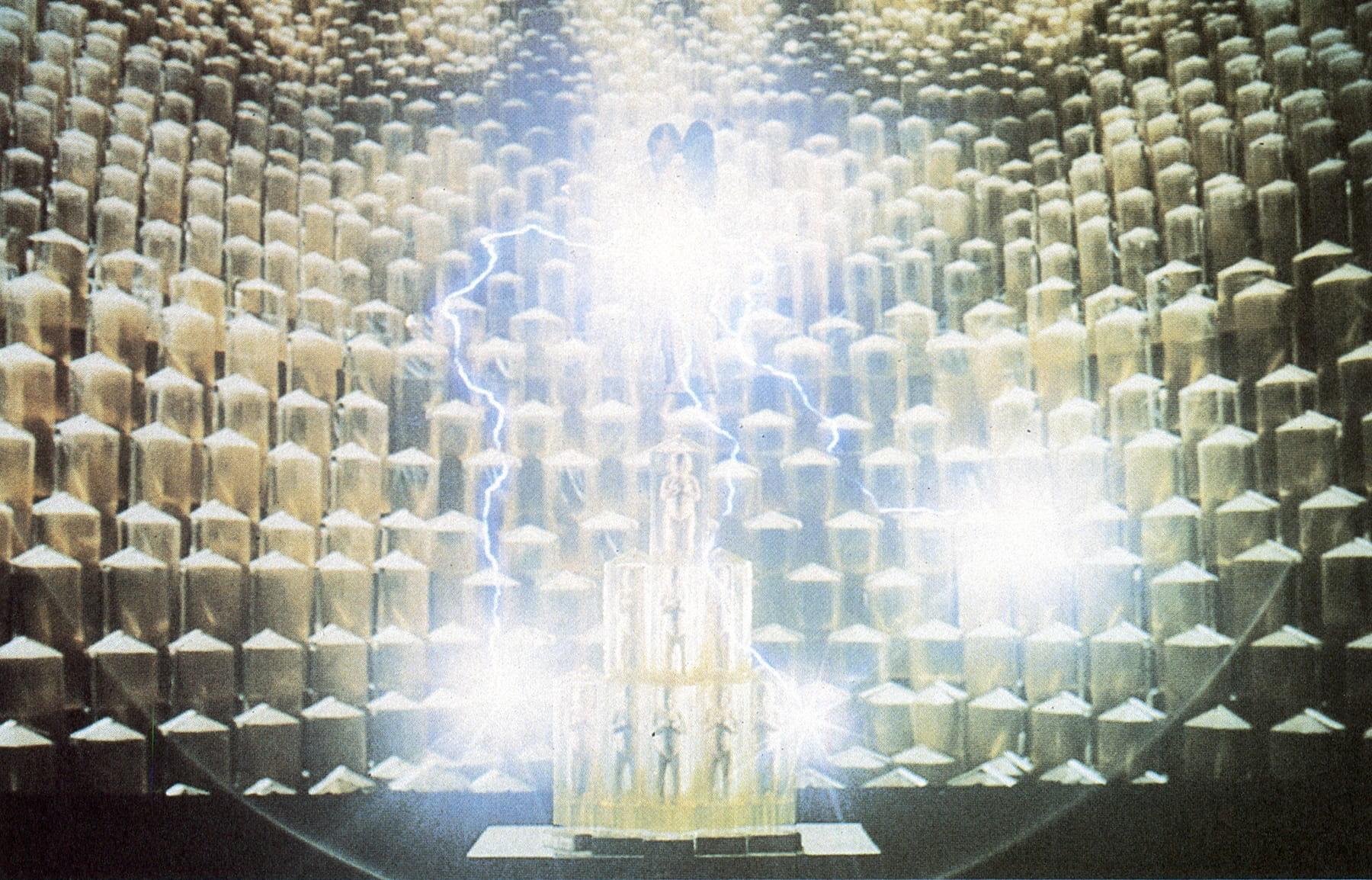

A look into the laser technology and lighting practices that made this 1985 sci-fi horror film possible.

Ask anyone in the business of making special effects movies what he wants and you will be told, “Effects no one has ever seen before.” This reply is common, expected, and even held to be amusing among the workers, technicians, and specialists in the elite field of motion picture special visual effects.

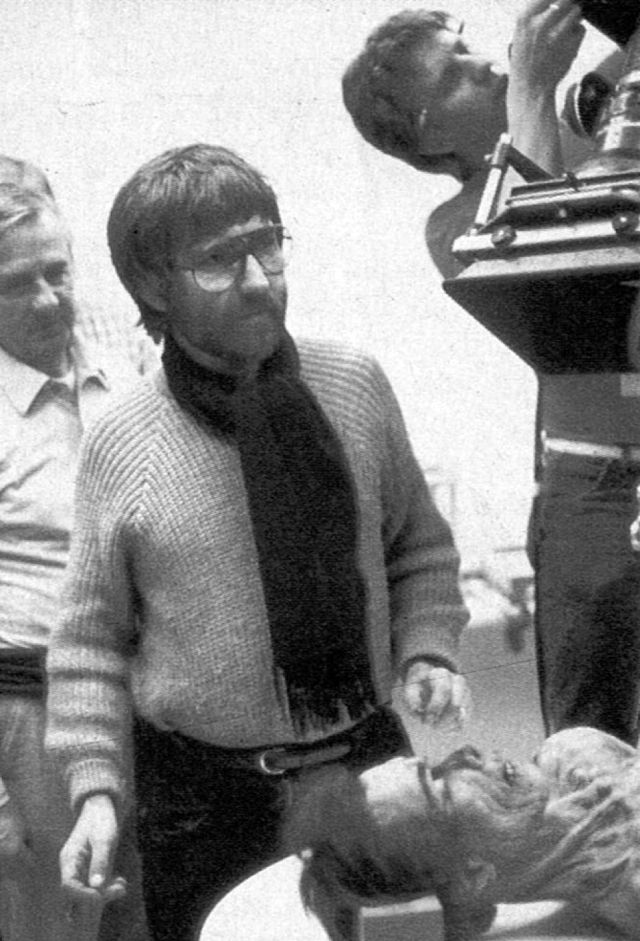

Yet, however amusing, the fact remains that with millions of dollars riding on each new effects film, original, never-before-seen effects are routinely demanded by producers and directors and, perhaps more importantly, by the ever-more sophisticated movie-going audiences. The risks of reaching into the unknown to find ever new effects is simply part of the act and one of the prime reasons why there are so few noted practitioners of the art. The romance is attractive, but few are able to meet the challenge. Lifeforce, at $22.5 million is the most lavish production to date from Cannon Films. The special effects were done by Apogee, Inc., and its complement of master craftsmen. Tobe Hooper, the maestro of reality where none exists, is director. Lifeforce is not only full of new, delightfully frightening, and challenging special effects, it is a smoothly crafted, mesmerizing film as well. The story concerns the invasion of London by alien, vampire-like creatures, and the British Government’s dilemma over whether to nuke England or fight the aliens. The picture co-stars Steve Railsback, Peter Firth and Frank Finlay and introduces the beautiful French actress Mathilda May, who, as an immodest vampire, remains naked through a large portion of the film.

“The spirit of the book is certainly there from my interpretation of the reading,” Hooper says. “Though Colin Wilson’s novel was set in the future, I made it a contemporary piece for identification. Also, I tied in Halley’s comet, where they make the find of the alien ship. It has been millions of years in the coma of Halley’s comet, traveling as a parasite of sorts. But, basically, I think the movie embodies the same spiritual feeling that Colin Wilson intended.”

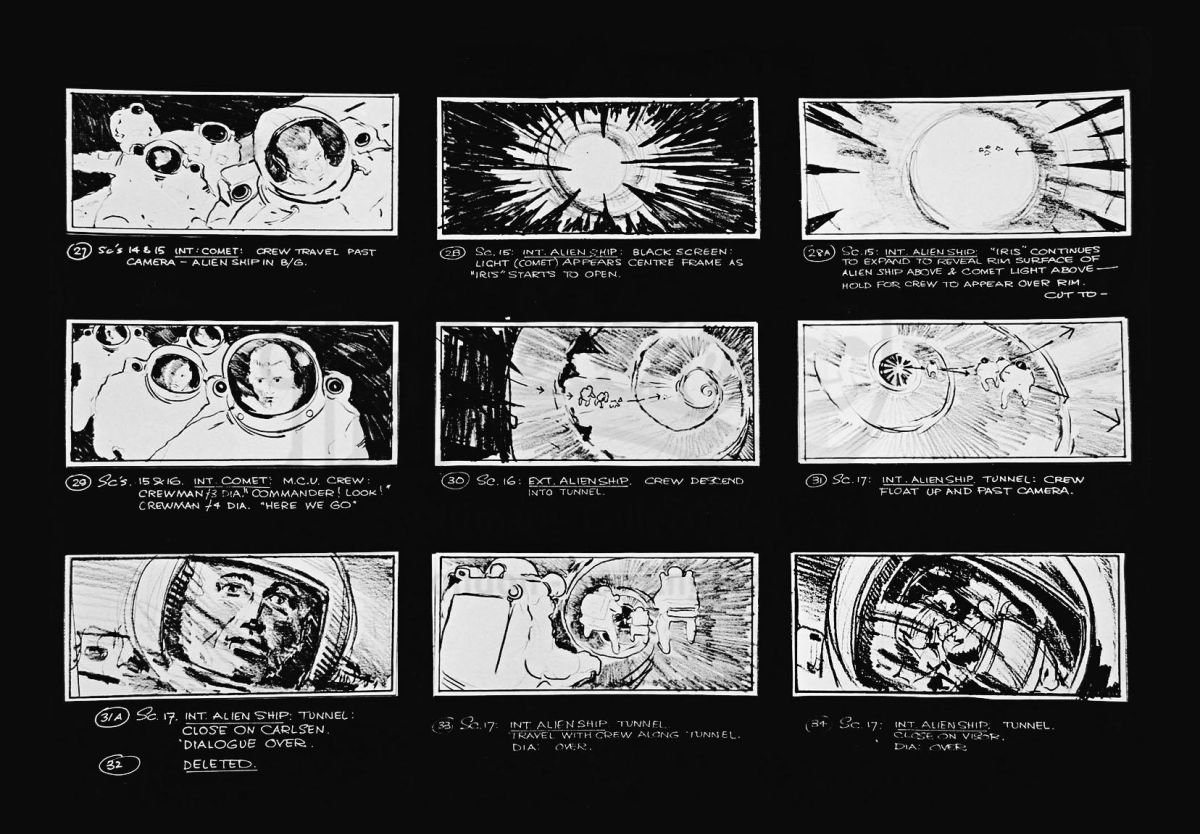

Even though Lifeforce is an unconventional movie in many respects, John Dykstra knew that his work on it should begin in a conventional way, breaking down the “wishlist.”

“Special visual effects storyboards are a wishlist,” explains Dykstra, “They include everything that the director and producer and other creative persons involved in the project would like to see in the film. Some of the storyboards are necessary to tell the story, others are embellishments, and another group falls under the title of, ‘Let’s wow them!’ The budget normally decides what stays in.”

Dykstra realized the challenges of doing Lifeforce “included having to work in Britain for a portion of the production, shooting the live-action components that would later be combined with post-production and process, seeking out the capabilities of British crews and British technology to provide those aspects of the film which would allow us to work with equipment that was available in Britain rather than having to ship it over, and determining what portions of that equipment had to be brought from the U.S. in order to meet special requirements”

Dykstra flew to London to discuss the storyboards with Hooper, art director John Graysmark, associate producer Michael Kagan, director of photography Alan Hume, BSC and the British crew, including Nick Maley, who did the impressive prosthetic effects, and John Gant, who did the challenging floor effects. “We talked over the storyboards,” says Dykstra, “to determine how many special effects scenes could be afforded, how many were necessary to tell the story, and how the work was to be divided between the different types of effects.”

A firm believer in planning ahead, Dykstra would have been happier with a longer period of pre-production, but allowed as how things went very well because of Hooper’s knowledge of effects and the professionalism of his coworkers.

“We looked at the storyboards together and began doing the budget, providing costs for miniatures, original photography in bluescreen, and in a conventional process, both still and motion picture. Integrated into that budget was the work that was to be done by technicians that we would be working within London.”

After breaking down the designations of specific areas of involvement, it was determined what visual effects work would be done at Apogee and what work would be done in London at EMI Studios.

“Since completion of live-action photography was planned to precede any postproduction addition of visual effects,” Dykstra says, “We decided to concentrate fully on the photography at hand before even attempting to determine the quantity of postproduction work to be done later in Los Angeles.”

Apogee’s commitment to the “photography at hand” took the form of Dykstra working very closely with Hooper and the live-action crew: “Some of the things that we had to determine specifically, to work in conjunction with live-action, other than the normal kinds of things that you work out such as process photography, bluescreen photography, and prosthetic gags that work with pieces that are to be added later, included some effects that are unique to this show. For instance, when the vampires are in their disembodied state, they travel as light energy. These disembodied vampires move through the streets of London as bright ‘bolts’ of energy that suck the lifeforce from people, leaving shriveled corpses and massive destruction behind them. To achieve this effect, we needed highly controlled reactive lighting to occur during the live-action shoot.”

“John and I knew basically the kind of ectoplasmic visual we wanted to happen,” explains Hooper, “but we didn’t know exactly what it looked like. We interpolated the reactive lighting to match the lighting that John would create and later put in the atmosphere; the spirit life.”

About the scenes where the ‘bolt’ travels through the streets of London, Dykstra says, “When we worked with the people in the streets who were being devastated by the vampires, we used a light that was mounted on a cable that moved along above them, casting shadows on the walls and the surrounding area. Later, on our stage at Apogee, when we added an artificially generated light flare, it appeared as though that light flare was really the source of illumination for those people.”

“It was all prefigured from the boards,” Hooper adds. “We knew where we had to have our special reactive lighting. John and Alan Hume worked together on coming up with various devices that would give off different kinds of light.”

To Dykstra, reactive lighting was crucial and he gives a lot of credit to Hume who “was very much involved in making certain that the reactive lighting worked well.”

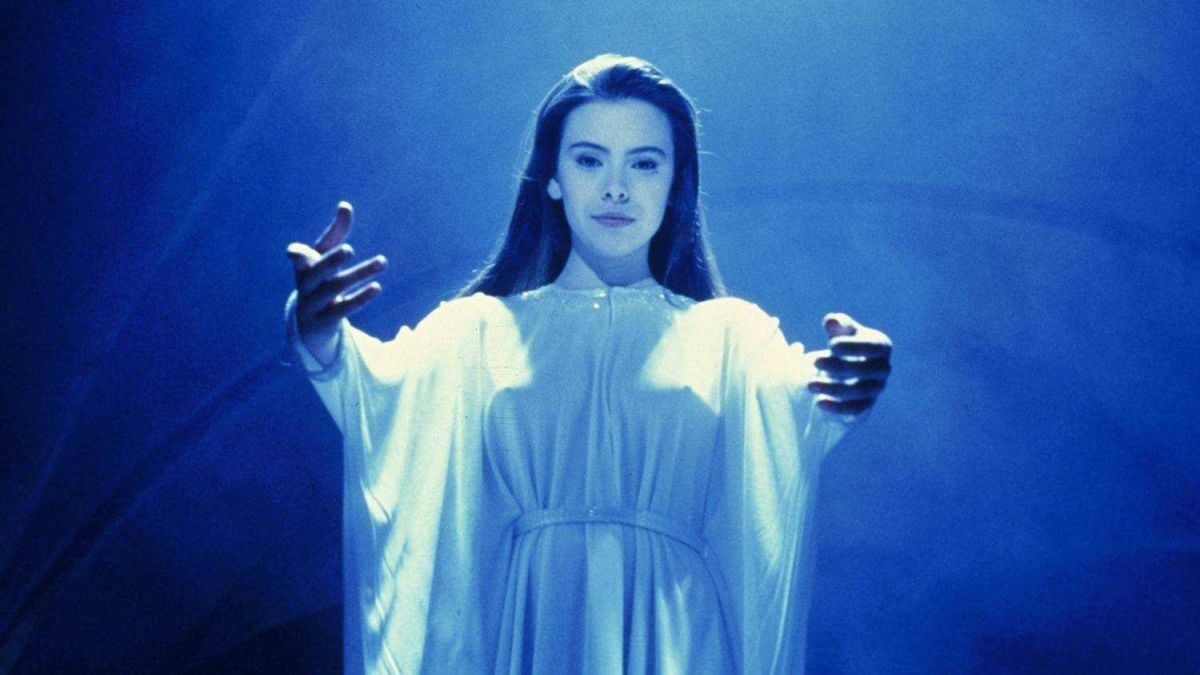

Another environment that demanded reactive lighting was in the scenes in which humans were facing attack by the Primary Vampires. Dykstra explains, “When a Primary Vampire, a vampire who is from the alien craft, attacks someone, a halo of lifeforce energy appears around them. Mathilda May, who is a Primary Vampire, has a very unique aura of light appear around her when she seduces her first victim, the guard who was set to protect her. A moving halo of energy is created around them.”

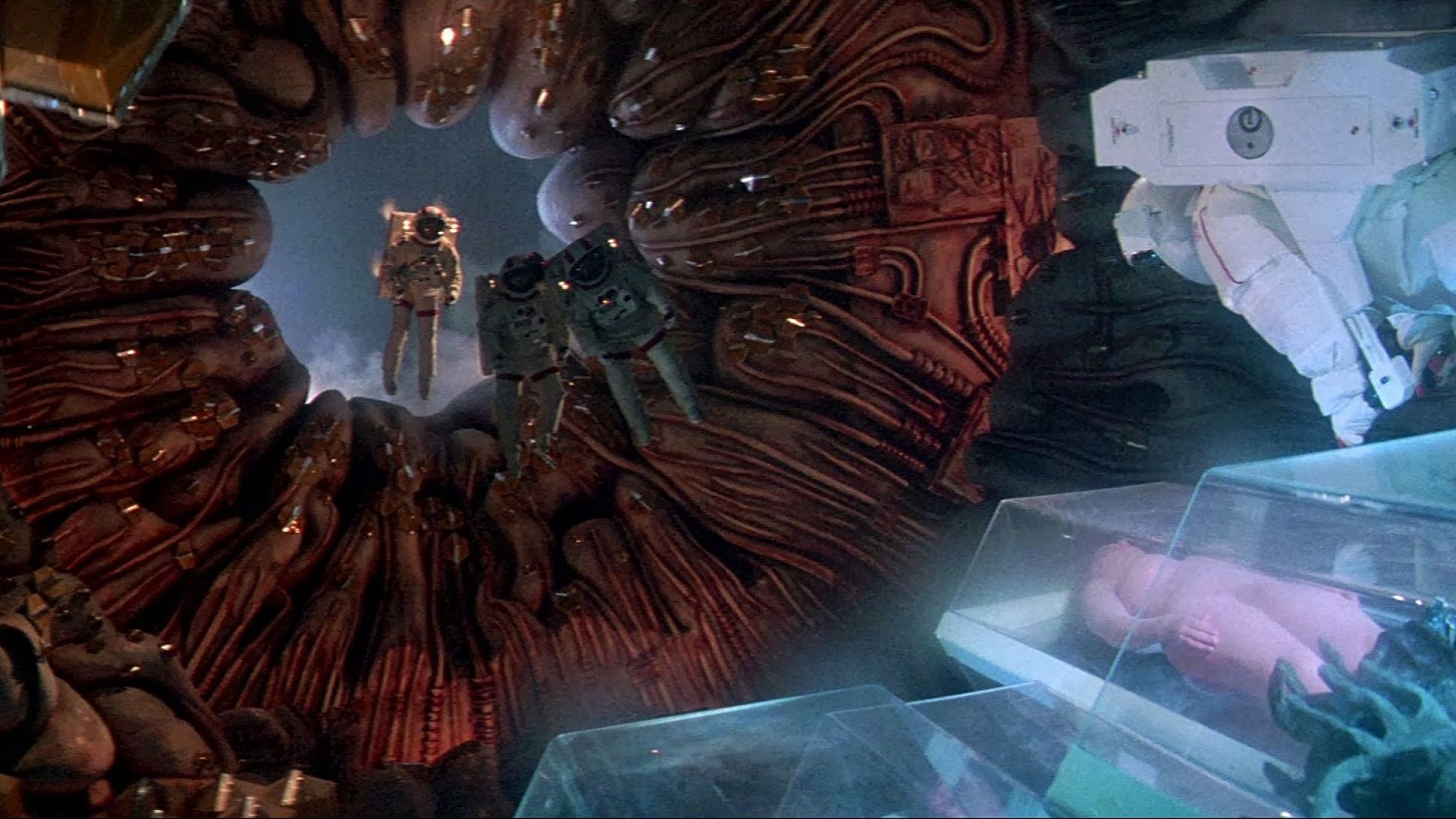

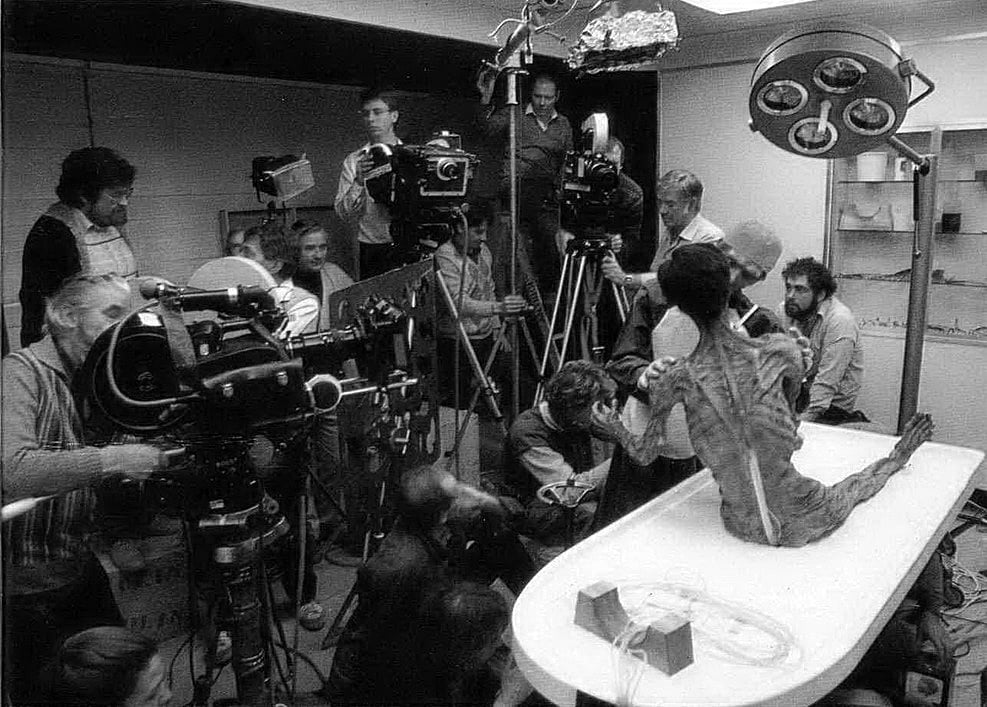

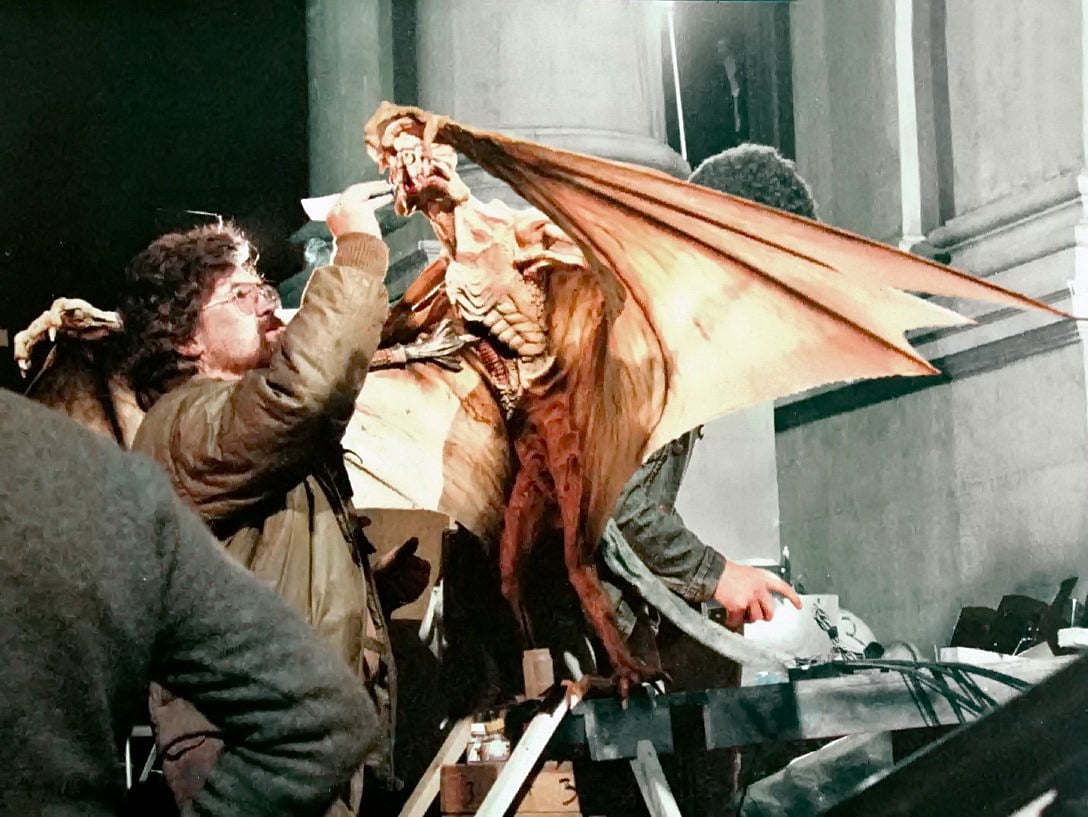

Of another such scene, Hooper commented, “Nick Maley made some prosthetic devices that were life-size, full-size articulated robots that were incredibly shriveled and skinny. They were controlled by radio and cabling and some of them would take twenty people to operate. John and I figured out the reactive light on them, then incorporated that when the spirit force, the lifeforce, is drawn from one of the prosthetic robots to another. The robot losing his lifeforce shrivels. These devices had vacuum pumps and liquid bladders that were in sync with one another, so that as one object took on the lifeforce and expanded back to its normal self, the other normal-looking robot would deteriorate to a shriveled state. We called them ‘walking shriveleds.’ They are so life-like that people thought they were very skinny actors with makeup appliances on them, but they’re totally mechanical and electronic.”

“The reactive lighting involved in the deaths of the two male vampires was also critical,” Dykstra continues, “We used flashbulbs that were specifically timed to change colors during the scene so that when we changed our colors subsequently during postproduction, those colors would be reflected in the live-action portion of the photography.”

“Sometimes we used as much as $15,000 worth of flashbulbs just to shoot a single scene,” Hooper comments. “The light was alive in those shots. It was more than just strobing; it was a very strange effect we used for the reactive lighting for the spirit lights.”

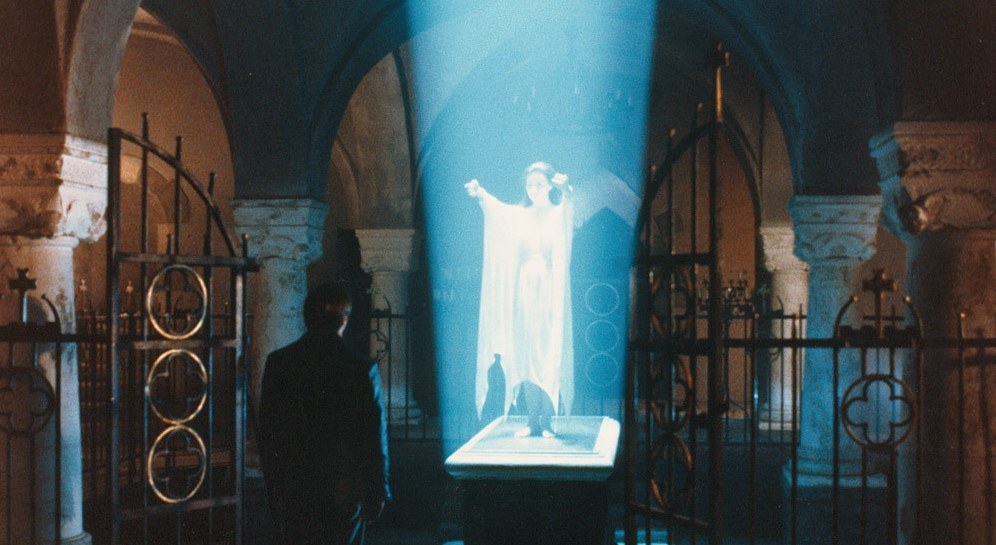

Once Dykstra had worked out the live-action portion of the material from the point of view of reactive lighting, he still had to confront process. He says, “That came at the end of the schedule and in this particular environment, we had to create the interior of a cathedral. It turns out that most churchmen don’t want their cathedrals to be in a vampire movie, so we photographed the interior of an ancient hall in London that became our cathedral. We projected the picture of that interior onto a screen, provided a foreground, and the rest of the scene was primarily a front projection piece.”

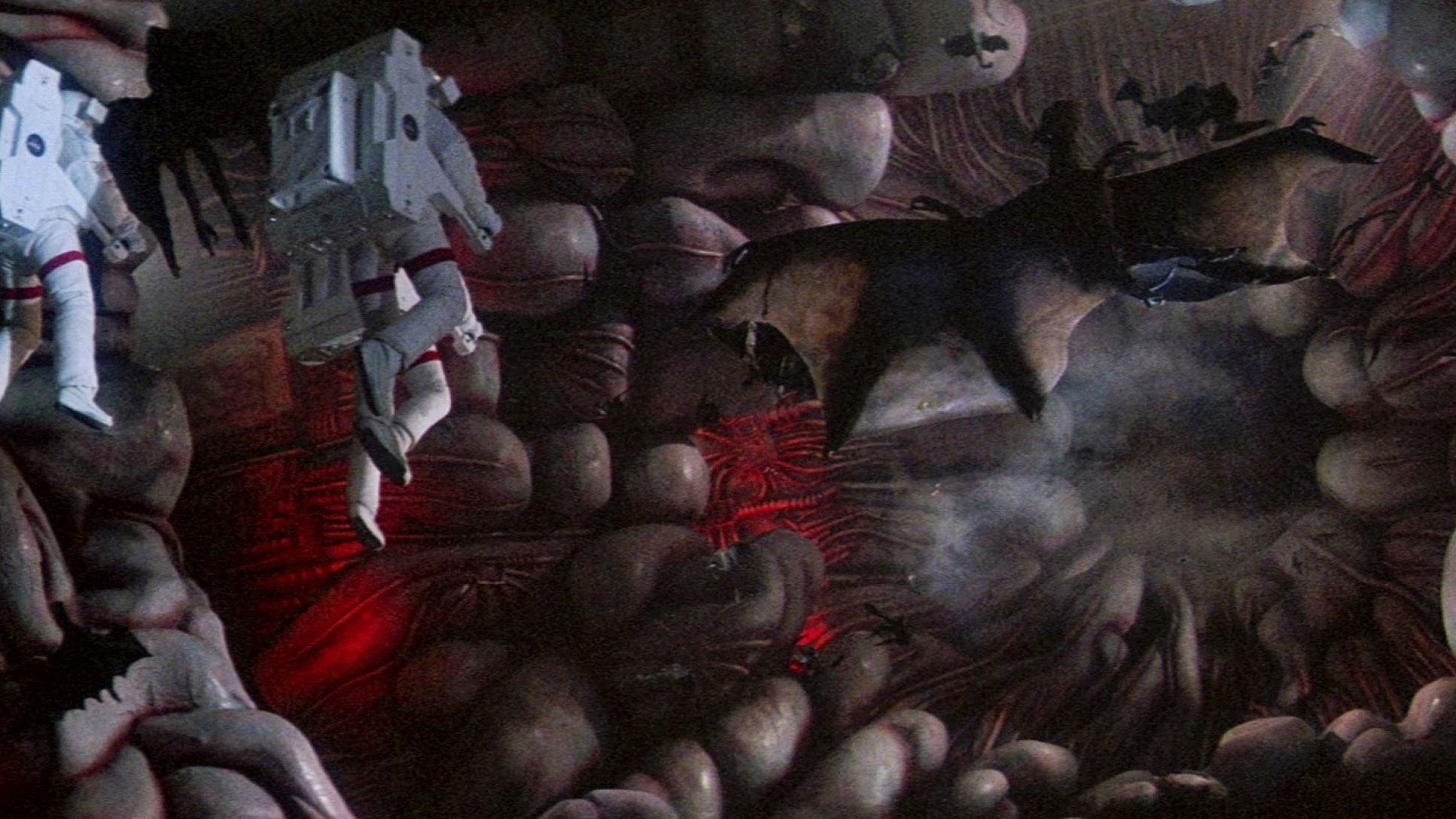

The cathedral interior was photographed on large format and presented on stage six of EMI Studios, which Dykstra describes as “250 feet by 100. We put a 70 foot screen at one end of the stage and because the field of view was wider than the screen could provide. We had to bring in ‘wings’ in front of the main screen. The wings were also covered with front projection material and were placed in such a way that their edges occurred in shadow areas of the still plate and were netted down to reduce exposure so they balanced against the background. We ended up with the stage floor littered with bodies, a few foreground pews and rails, and a cathedral interior which is all on screen. The balance worked very well. In conjunction with the front projection photography, we did a light effect, which was a beam of light going up through the top of the cathedral representing the lifeforce being transmitted to the alien ship. That was by using the other side of our fifty-fifty mirror and putting a very, very carefully cut mask in front of an illuminated surface to make modulated light move up through the cathedral. The final aspect of the material that we did in Britain included the transformation of one of the prime vampires at the end of the film from a human shape into his original batlike form. As it sometimes happens, this was a decision of the moment, as opposed to something that has been carefully planned. These moments are fun. We discovered that the use of a CO2 fire extinguisher to obliterate the image of the human form and then reveal the image of the batlike form on a soft cut cross-dissolve was very effective.”

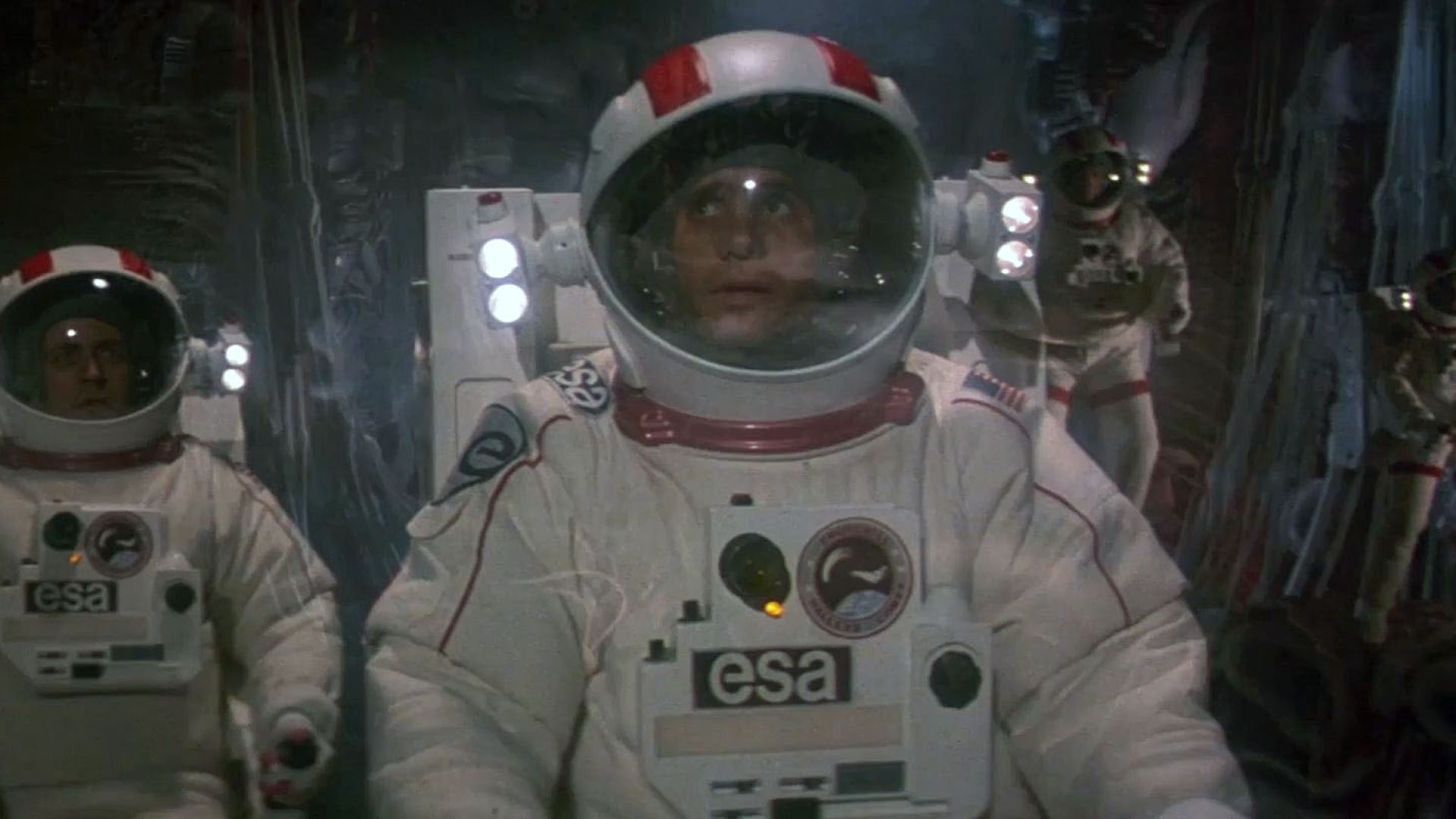

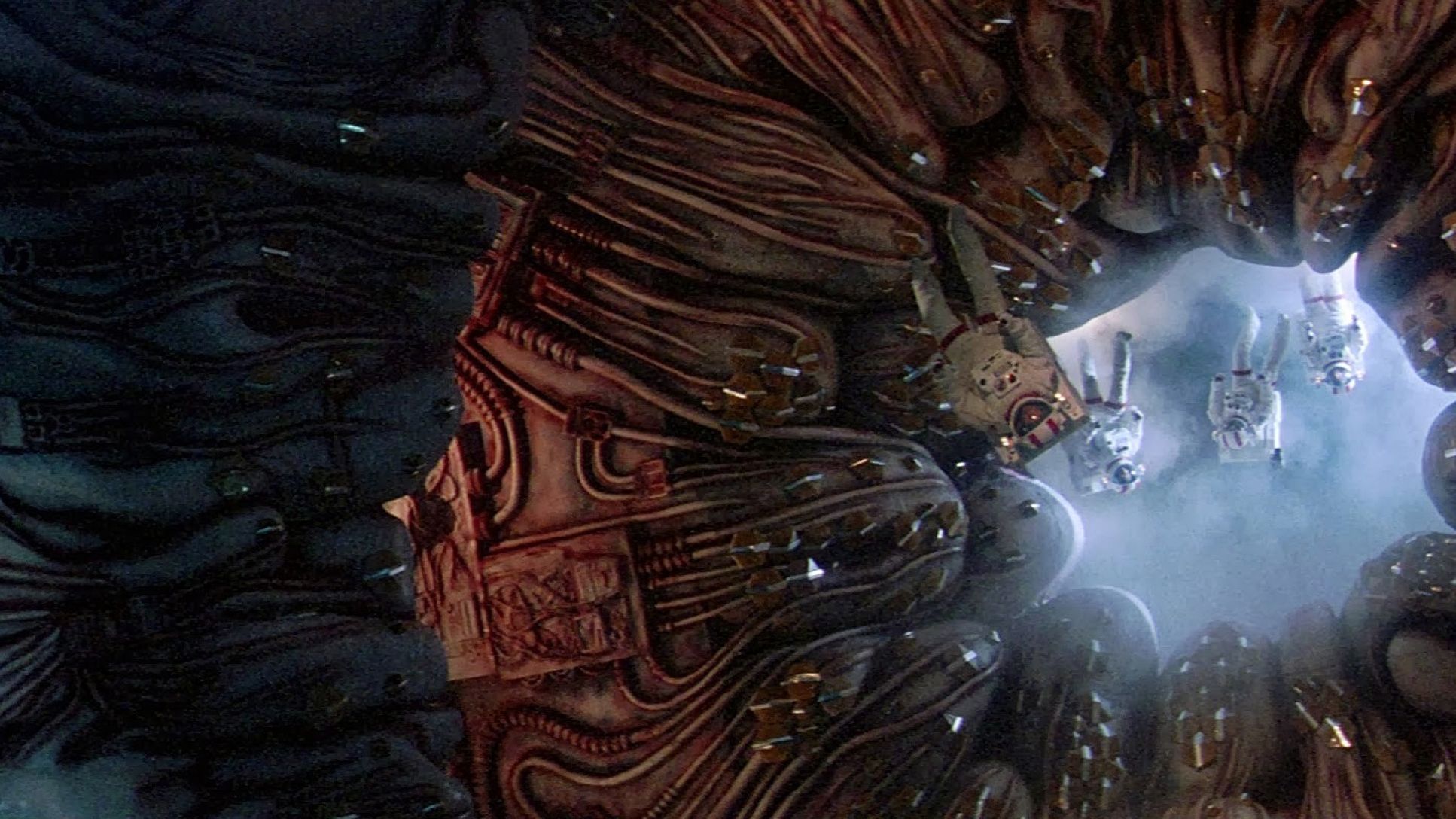

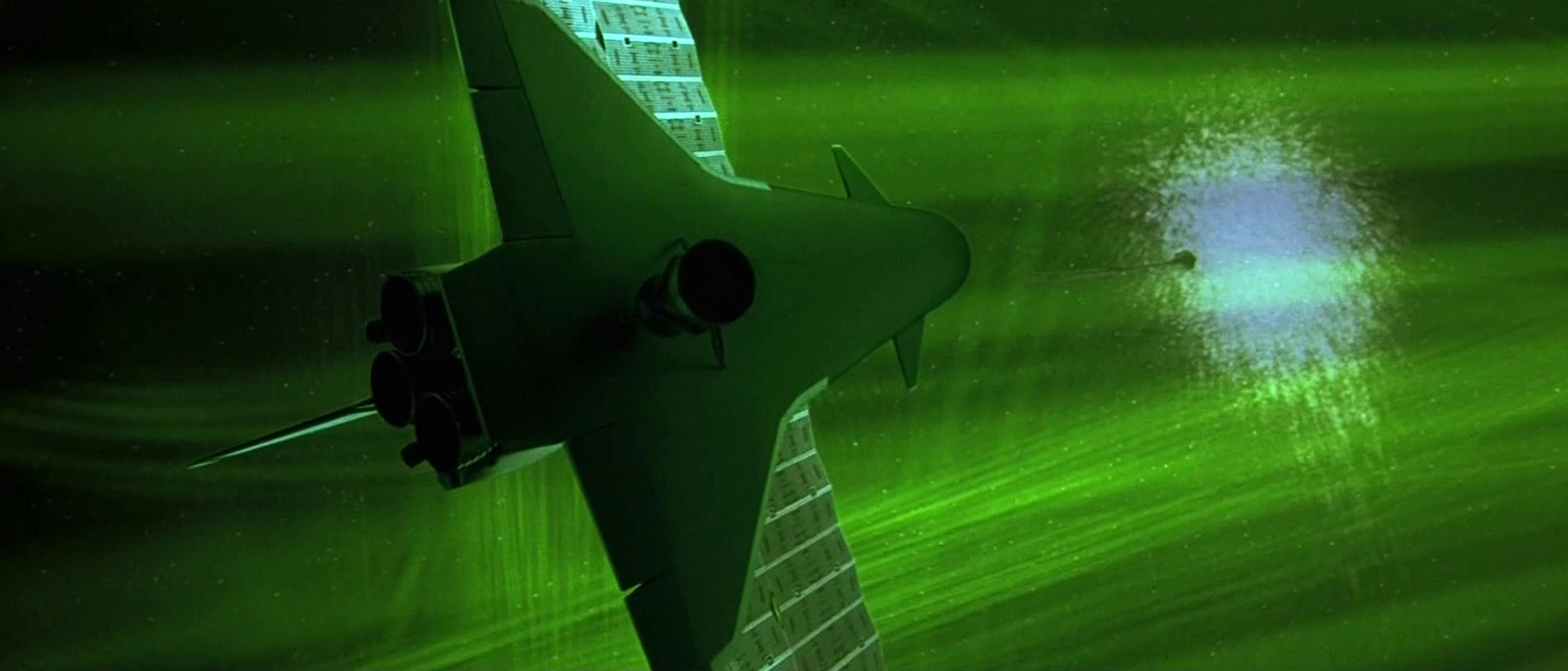

Another facet of Apogee’s work involved bluescreen photography. Dykstra says, “That included our astronauts as they approached the alien ship, when they are enveloped in the interior of Halley’s comet, the coma of the comet, and subsequent to that, the interior of the alien ship when the astronauts explore it. Because we needed to see the faces of the actors in these situations, we used the bluescreen. For portions of this material, we used a conventional transmission bluescreen which we built in London. We used our transmission screen with its particular formulation, which we built in conjunction with Stewart Film Screen, to do the closeups. For the wide shots of the astronauts hanging on wires in front of the large front projection screen, we used the Blue-Max system which was also used in 2010 and Dune.”

Now, in postproduction, the interest in reactive lighting has moved to the lasers that are replacing that lighting. Dorney, who retains a guileless enthusiasm for his work and is rated with the best at what he does, went on to say, “We all know that lasers go in straight lines forever, but for Lifeforce, we bent laser beams. So, how’s that? The laser lights are incredible the way they are bent and shaped and controlled. They don’t look like anything you’ve ever seen. It doesn’t look like a laser at all. Not to sound corny, but it has almost an organic look. The colors worked well, too. We wanted blue, red, and magenta for the storyline and had no trouble at all getting those...and, in most cases, they were saturated colors, so pulling mattes was very nice. Also, the look was supposed to be contrasty in these units, so that helped, too. But it was the actual image the laser light gave us that was so nice, so different.”

“We had to figure out what a human soul looks like when it leaves the body,” mused Dykstra. “No mean feat considering I’ve never seen a soul do anything, much less leave the body.” As it turned out, the image of the soul leaving the body was less difficult to achieve than an image of the interior of Halley’s comet, but Dykstra’s concerns were broader still. “The components that we worked with to provide these storytelling elements had to have some things in common,” he explained. “One, as always, was that it be unlike anything ever seen before; two, it had to have some basis in scientific fact because viewers have become so well educated; and three, it had to be done with a common enough technique to allow many shots to be achieved within a reasonable period of time and within a reasonable budget.

Armed with the tools of laser technology, Apogee got down to the business of creating an image that, as Dykstra envisioned it, would elicit from the audience a sense of the ethereal. Dykstra knew what he wanted. “It should be veil-like, translucent, something that you feel is tangible though intangible. It should have a recognizable quality or theme, either a color or shape or movement that will cue the audience when they see it.”

That was the theory, but what was it like in the trenches? “First of all, laser photography is always a little bit funny because the rules are different,” states Mat Beck, who shot laser photography for Apogee. “The multi-pass photography made it more complicated still, and it was difficult because of the nature of the hardware to guarantee that we could ever get back to something we had discovered because often what we were working with was just a reflection from a piece of treated glass held in space.

Can laser beams really be bent? “Fortune was with us,” Dykstra says, “because a lot of the concepts which were relatively untried turned out to work. Those concepts primarily included ways of manipulating laser light to achieve a three-dimensional form in a two-dimensional medium that had movement within itself and upon itself and that had a transparency that was ghost-like. So we refracted lasers, we reflected lasers, we bounced lasers, and we scanned lasers, and as a result, we came up with not only graphic images but images, by virtue of their narrow bandwidth of color, that were unique. And we used them.”

“I’m not certain exactly who came up with the method of rotating tortured mylar on a drum,” Beck comments, “but John Dykstra, Douglas Smith, and his assistant Mark Gredell worked on it originally. John Sullivan did some effects with it, too. Then Maryan Evans and I changed it some. We made it easier to manipulate. Sometimes the drum we were reflecting the laser from would not be dead on center. We had the sense of the light flowing, but it would wander. We had to program it to keep it dead on or the bolt would be moving around in a funny way. However, we wanted the tail of the bolt to stay about right so we had to do a little twiddling on it to make sure it fit. Sometimes we had to do a number of different elements that would be laid on top of one another, some faster, some slower to give it a sense of dimensionality and, also, by different elements moving at different speeds we got interference that would make it more interesting.”

Had cameraman Beck been too long with his lasers? Could anyone understand what he meant about torturing mylar or twiddling the tail of an energy bolt? In fact, a laser language came in to use at Apogee during this busy period of experimentation and effort and terms such as “snakey licks,” “A to B Lifeforce,” “pop tarts,” and “surrounds” seemed perfectly in keeping with the charged atmosphere.

Beck says that at one point, “There was so much laser photography to do that three out of seven stages were producing it.” John Sullivan, with Josh Morton and Bess Wiley as his assistants, was shooting laser photography in a special area on stage two and John Fante, with Eric Peterson assisting him, was shooting lasers in a special area in the model shop near stage three, where Beck and Evans were working.

The “point” that Beck referred to was approximately two months into post-production when Caren Marinoff, Apogee’s production coordinator, had computed enough information to realize the then-present schedule would not meet the deadline. She says of those hectic months, “The deadline was unchangeable. There was nothing to be done but hit it. So we doubled our photographic staff and began rigging up special areas and splitting up stage space. We even took over the large area near the coffee machine.”

It was in the coffee area that D.P. Gregg Heschong, with his assistant Chuck Schuman, began testing flowing granules of anthracite in their search for the perfect comet.

“The schedule for Lifeforce was tight, but totally under control,” Marinoff asserted. “John Swallow, who coordinated the effects animation, and I worked closely together. We had our stages in full operation from 8:30 am until 10 and 11 pm, five and six days a week.”

Dorney says of this busy period: “We had six fellows in optical plus the roto department and animation working. Everyone was feeding units through editorial down to us. Jerry Pooler and I were on camera. Paul Bolger, too, at times, as well as being a line-up man. Dennis Dorney and Richard Gilligan were lining up and Alan Spilkoman was helping us in optical.”

Apogee’s animation department is supervised by Harry Moreau, who was justifiably proud of the quality of the work produced by his staff: Randy Fuller, Olga Craig, Chuck Warren, and Kathleen Quaife.

On stage one, Douglas Smith, with Glenn Campbell assisting him, was shooting the shuttles and other models, the puppets of astronauts, and the very demanding Halley’s comet. Smith says, “It was determined early in the production that the comet would be a yellowish-green. That, combined with the fact that comets emit a soft rather than a sharp, contrasty light, made it difficult to make the large size of the alien spacecraft be apparent. There were none of the usual visual clues to help the viewer relate to the scale, no window lights, doorways, or walkways. So every shot had to be treated individually to force, through lighting, extra detail from the model while it was in the presence of comet light. Our gaffer, Lee Pogoler, helped us work through the worst of our lighting problems. With a few minor exceptions, I’m pleased with the results we achieved.”

Roger Dorney recalls some difficult moments, too. “When you’re pulling mattes, rotoscope is the hardest thing to pull out because you’re at the mercy of the guy drawing the line,” Dorney explained. “You can project it like we did in a large format and then hand draw the images, but you’re still at the mercy of where that man sees that line. Also, in this particular show, we had to contend with gross light changes in the background with light values going from a range of six to eight stops. A lot of the frames don’t have any information on them, but the poor guy drawing the line has got to draw a line in there, a frame to draw to. It gets very difficult. If you have a standard evenly lit scene with some kind of contrast to it, you can see the line; but in this movie there were some frames with plenty of contrast, some were dark, some were six stops lighter than the previous frame.”

These were moving, streaking objects, not cartoon animation where you can get away with no streak.

“Lifeforce has seen the best roto work that has ever been done here,” claims Dorney. “We got into a large format and had a very good crew working. The registration was excellent from my standpoint. I get very critical of it because the registration has to be there; the sizing and positioning has to be dead on.”

The rotoscope format that Apogee used was three feet by one and a half feet as a projected image size. An animation stand format is about a third of that. The advantage gained with the larger format is that it cuts down the disparity between lines from frame to frame. Which, as Dorney says, “Gets rid of that hand-drawn quality. We had blowing, streaking hair to roto, plus flying objects that smeared by camera. They had to create a line to create a matte from those things. They had to do it right, too. They couldn’t create a hard, sharp line or else we’d have this silly looking thing going by. John Shourt, Michael Griffin, and Dan Hofstedt really deserve some credit.”

“The laser photography in Lifeforce is much better than cel animation,” Tobe Hooper says. “Its webby, tendril-like nature is excellent spirit stuff. It is far more exciting and you don’t know how it’s done.”

“One of the more complicated shots was when the energy bolt blows up a building,” Mat Beck recalls. “It enters the frame from upper right, goes down to the lower left, turns 180 degrees, comes back kind of horizontally along the bottom of the frame, and then up toward the upper right again. I mean, we had the light bouncing off the drum, so we could make it go left to right or right to left, but you don’t make laser light go around 180 degrees. I remember putting my hands around Dykstra’s throat at that point. Anyway, Jonathan Erland made up a rotating cylindrical rear projection screen with a tortured surface from which we bounced laser light onto a mylar mirror that we distorted dynamically. This allowed us to control the light and make it appear to snake. This was eventually coined as a ‘snakey lick.’ With all these curved and tortured surfaces we were finally able to make a laser beam go in circles. The roto boys snipped off a few pieces here and there and bingo bongo, we had the laser light doing what we wanted.”

“Although the laser provided us with an embarrassment of riches in the realm of imagery,” Dykstra admits, “providing on the screen cues to size was difficult. We used lasers to create the coma of the comet, which is scientifically defined as a cloud of small particles. That is fog, so we generated the concept that there were magnetic fields of force involved in the interior of this comet. That allowed us to create lines of force and those lines of force were created by refracting the laser light. The movement of those lines of force had to be very subtle because the interior of the comet is huge. That same refractive quality was used later when we made the energy of the individuals being attacked by the vampires. We speeded up the laser for that, making the scale of the refraction smaller. We also added an organic wave to it. Instead of moving in a straight line, it moved in curves like a snake. We tried to achieve a continuity of imagery throughout the film that tied the opening interior of the comet, and the environment in which the aliens lived into the subsequent action of those aliens. So, as you watch the movie, you get a sense of continuity between the lifeforce that was the comet, and that ethereal, supernatural — although recorded in practical time — phenomenon, which is the death of a human being.”

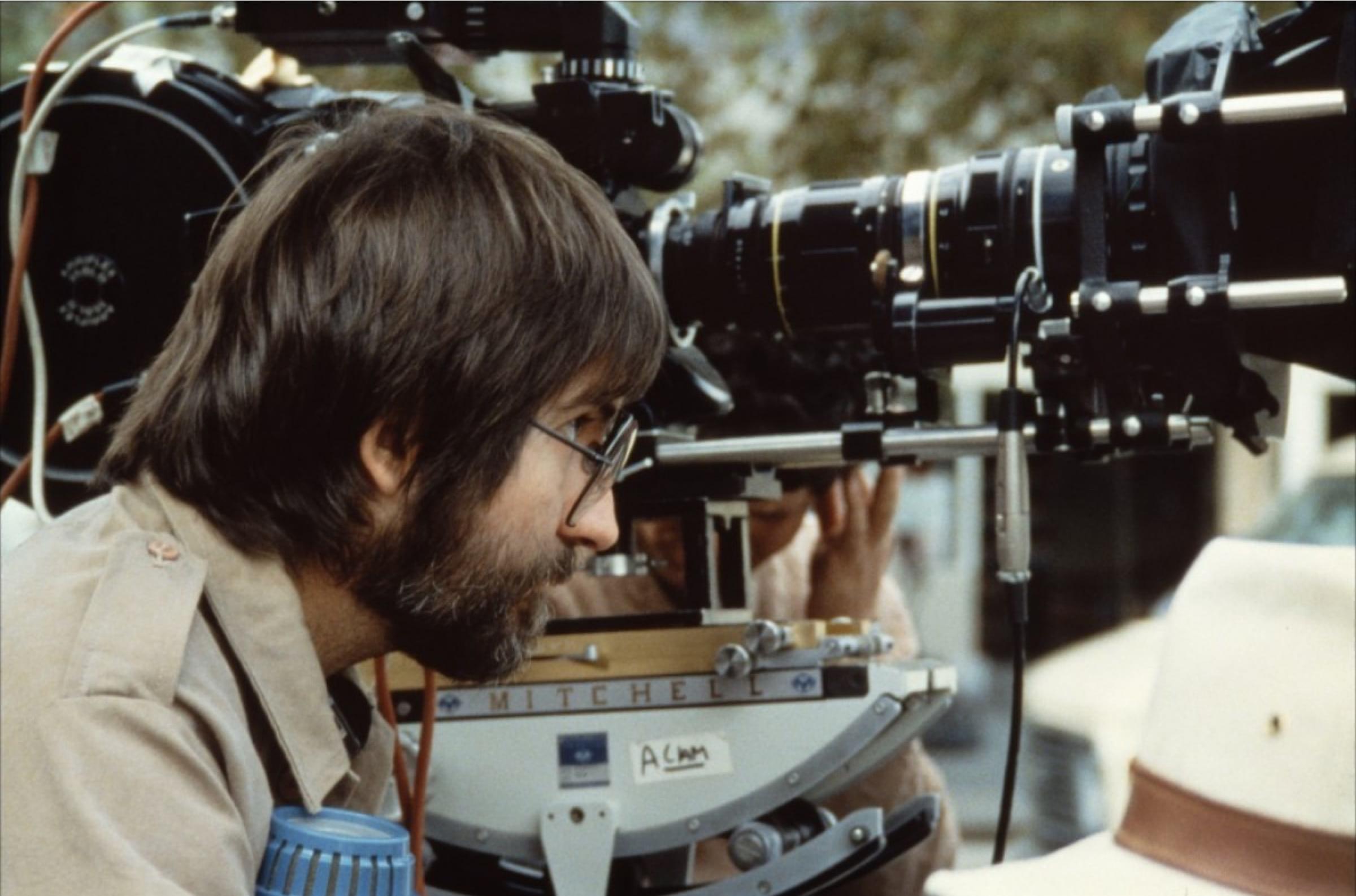

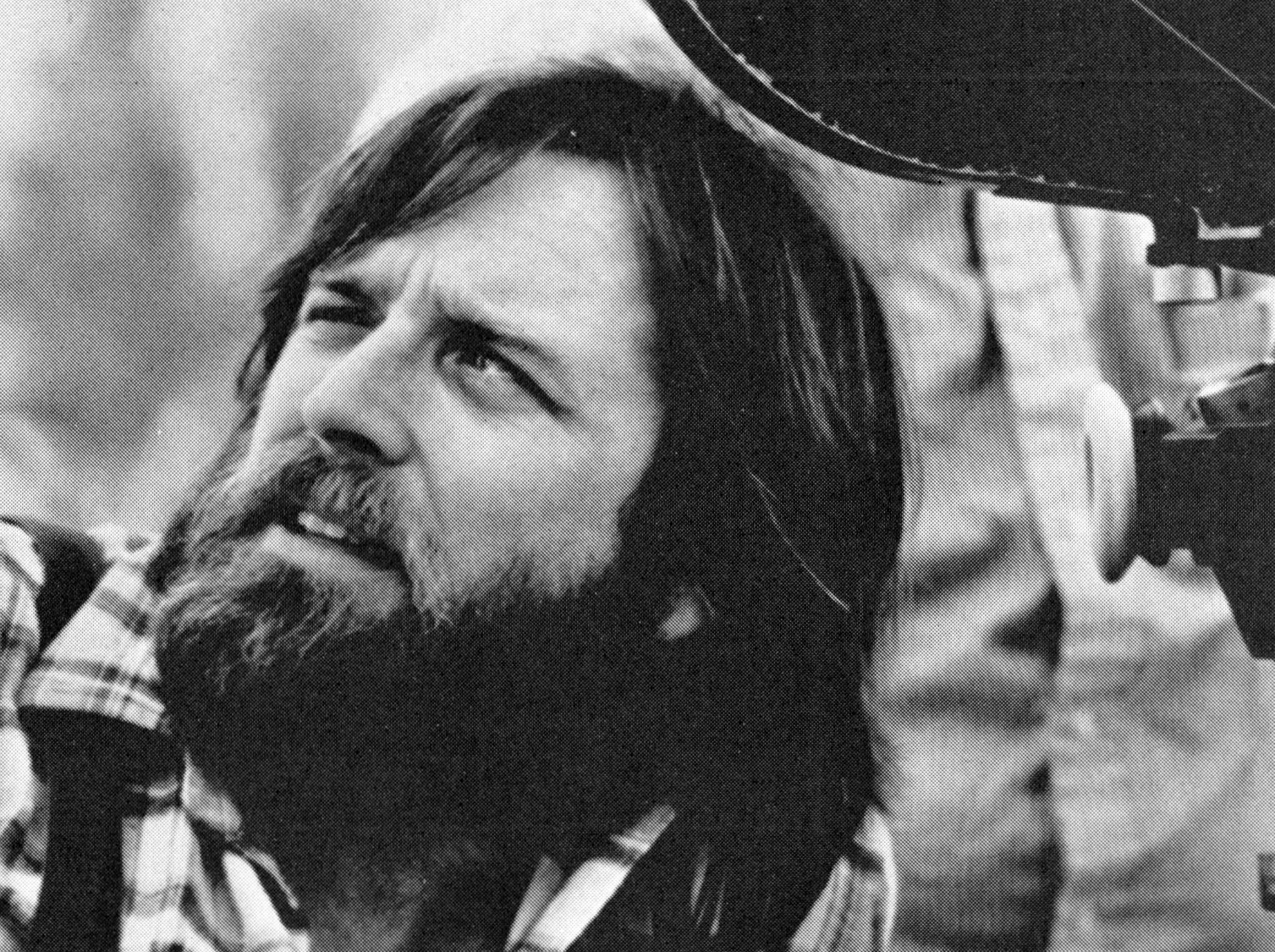

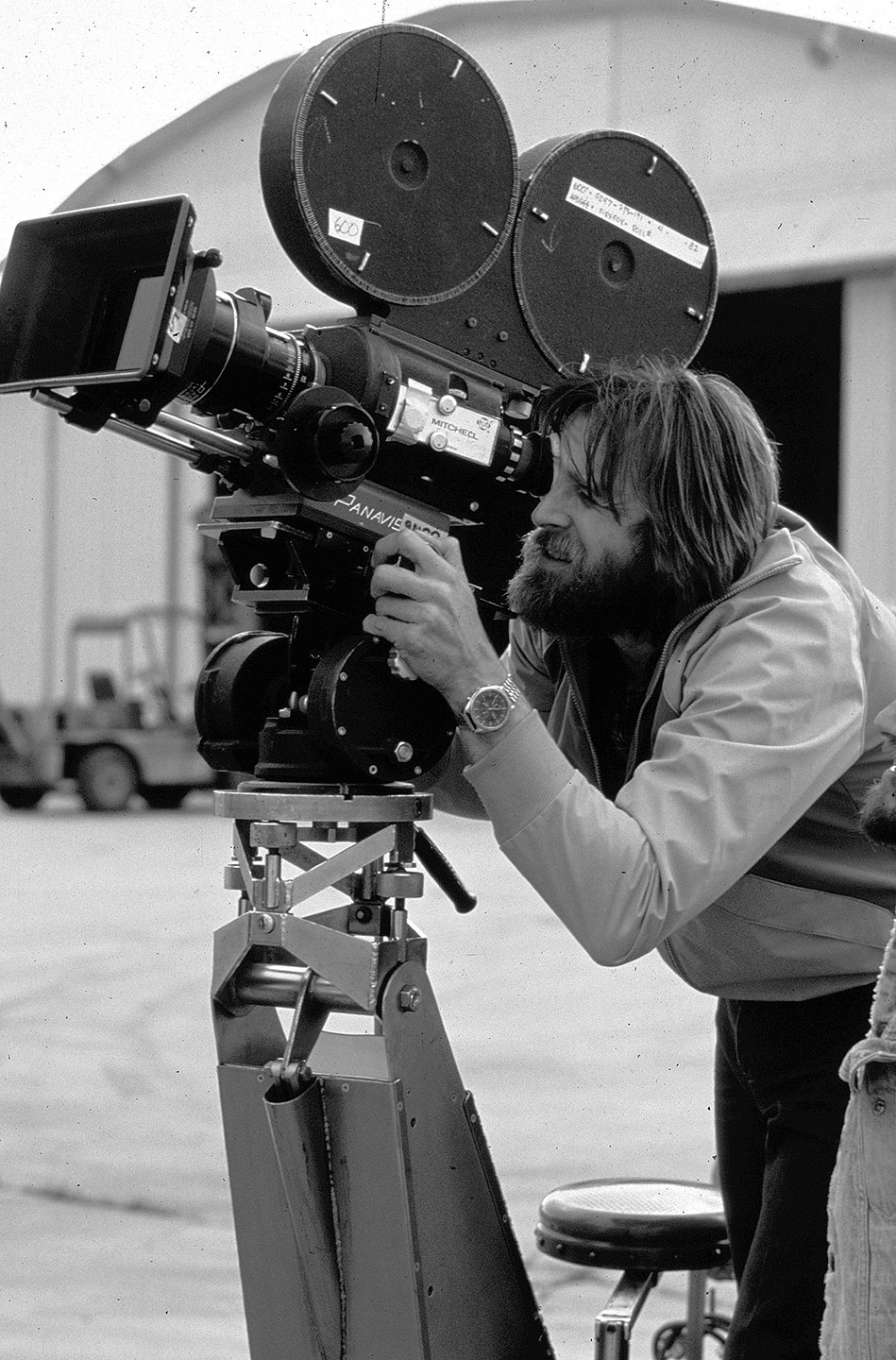

John Dykstra

Academy and Emmy Award-winning visual effects designer John Dykstra first developed an interest in photography with an eye toward helping to finance his college education. Soon after college, he served as cinematographer on a project sponsored by the National Science Foundation, gaining his first experience with shooting miniatures for a psychological study of responses to various architectural forms. Following this, he worked as industrial designer with Douglas Trumbull on the futuristic Silent Running, helping to create an early example of visual “realism” which has since come to define the science-fiction film genre.

Dykstra next worked for the Ruben H. Fleet Space Theatre in San Diego on a program entitled Voyage to the Outer Planets. Following this, he re-teamed with Trumbull to produce amusement park rides and aircraft simulator films, and experiment extensively in three-dimensional filmmaking.

At this time, Dykstra became involved with George Lucas on a project which was to radically change the look and nature of filmmaking — Star Wars, which contained the technological advances that set the standard for top-of-the-line special effects, not the least of which was the perfection of the motion-control system and the development of the camera which bears its maker’s name, the Dykstraflex. It brought him the 1977 Oscar for Best Special Effects.

The next year marked the creation of Apogee, Inc., which brought together nine of the world’s top special effects experts. The first project was Battlestar Galactica, the most expensive and technologically ambitious television series ever attempted, which was produced by Dykstra. His special effects netted him his first Emmy Award.

Subsequent film projects include Star Trek: The Motion Picture (for which Dykstra received another Academy Award nomination), Firefox and Outland. Apogee has also contributed to such films as The Avalanche Express, The Women in Red and The Natural. Today, the company operates from a 30,000-square-foot production facility which offers services in every phase of filmmaking.

Dykstra, Gregg Heschong and Mat Beck would all later be invited to join the ASC and are today active Society members.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.