Everything She Wanted — Billie Eilish: The World’s a Little Blurry

Cinematographer Jenna Rosher captures the whirlwind rise of the prodigious pop star.

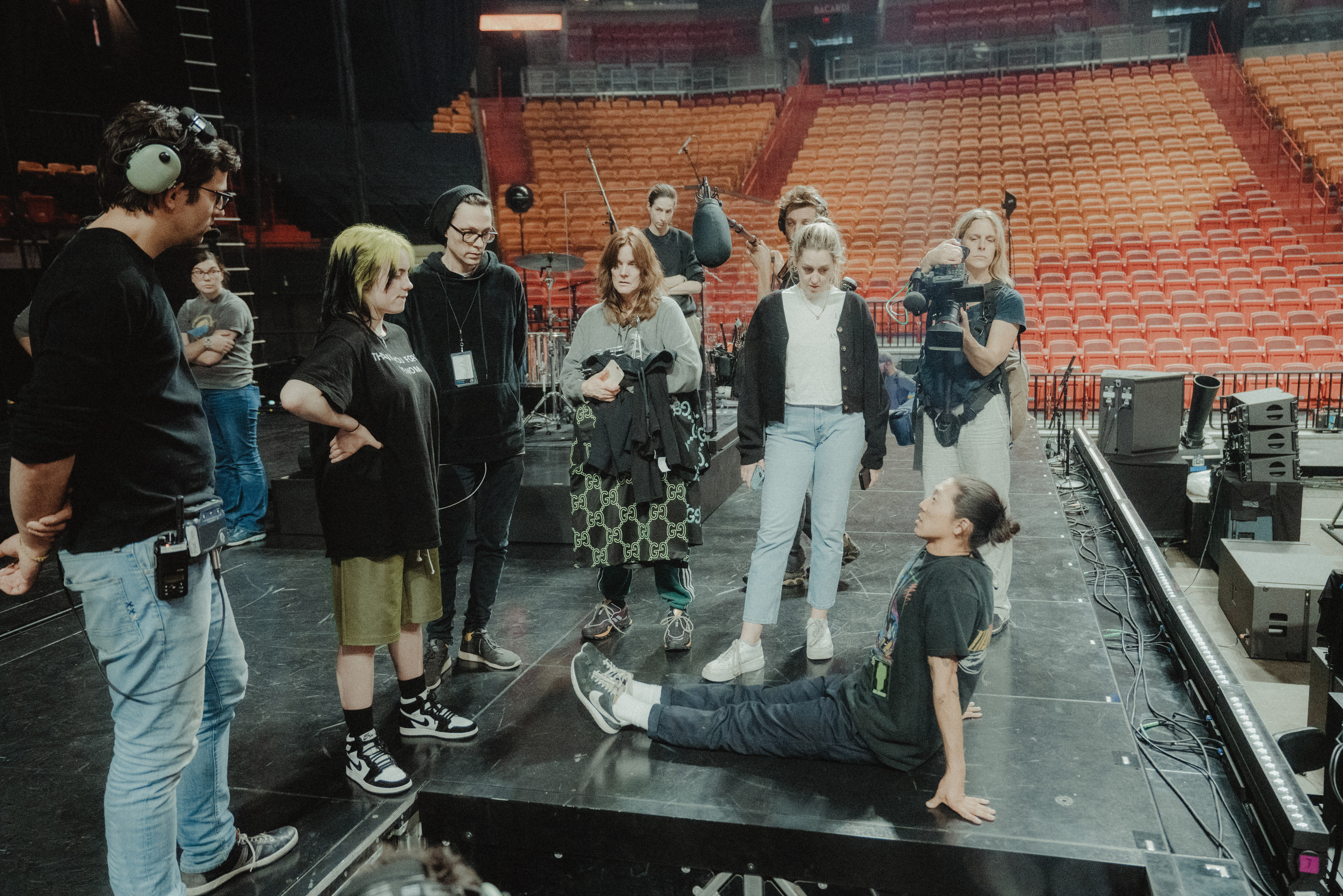

Photos courtesy of Apple

Billie Eilish made her mark with a voice that’s raw, real and intimate — so it stands to reason that any documentary about her should follow suit. And what’s more raw, real and intimate than cinéma vérité?

The Apple TV Plus documentary Billie Eilish: The World’s a Little Blurry is true to form. Up close and personal, it follows the singer from her viral breakthrough with her debut single “Ocean Eyes,” recorded at age 13, to her five Grammys by age 18. (She has since added two more Grammys to her impressive list of accomplishments.)

During the pivotal year when Eilish and her brother Finneas wrote, recorded and toured to promote her first studio album, When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go?, director R.J. Cutler and cinematographer Jenna Rosher stuck close by. The vérité veterans captured not only Eilish’s meteoric rise, but also the siblings’ DIY music-making process, the stress of touring, and quotidian moments at home with their parents. Their record of this journey is a coming-of-age story as well, with all the signs of a teen growing up: getting your driver’s license and first car, the travails of having a largely absentee boyfriend, goofy handshakes with your brother, and, since this is Billie Eilish, connecting with fans on Instagram Live with a pet tarantula crawling up your shirt.

Cutler cut his teeth on vérité. His first film as a producer was D.A. Pennebaker’s The War Room, which documented Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign, and he went on to direct multiple vérité films about pivotal figures in the zeitgeist, including political commentator Oliver North (A Perfect Candidate) and Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour (The September Issue, see AC April ’09).

Cutler had previously worked with Rosher on a short about L.A. chef Jon Shook, titled Fish, and he was a longtime fan of her work with documentarian duo Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady (Call Your Mother, Jesus Camp, Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You). Plus, he needed a cinematographer in L.A. who would be willing to come to Eilish’s house at the drop of a hat for an entire year. Rosher was all in. “If it’s a long project, documentaries often have multiple DPs,” she says. “But right from the beginning on this one, I thought, ‘I want to make this my own. I want to have some ownership in the visual storytelling.’ So I just made myself available whenever they needed me.”

She’d clearly caught Cutler’s contagious enthusiasm about the up-and-coming singer. “R.J. came to me and said, ‘There’s this incredible artist that’s come my way: Billie Eilish. I have no doubt this person’s going to go somewhere, and I want to make a movie,’” Rosher recalls. Shooting began in February 2019, when Eilish had just turned 17. The film’s pre-2019 footage was largely shot by Eilish’s mother, actor Maggie Baird, on her cellphone. Baird also had the foresight to set up GoPros in Eilish and Finneas’ bedrooms, where their composing and recording happens, and to record their activities with an iPhone. Altogether, the family gave Cutler 500 to 600 hours of footage, supplementing the 1,000 hours his team shot.

Rosher got her wish about owning the visuals, since The World’s a Little Blurry was largely a single-camera shoot, including most of the concert footage. Cutler explains the film’s aesthetic: “I wanted the same kind of intimacy in performance that we were aiming to achieve in day-to-day life.”

"I wanted you to feel Billie breathing. You were in the moment with her. I certainly didn’t want it to be what we’ve become familiar with [in concert films]: the swooping camera and shooting that’s all about technology. I was aspiring to the kind of shooting that defined Gimme Shelter. I was thinking about that first Madison Square Garden performance in Gimme Shelter, and I wanted that intimacy. I wanted a rawness, a presence. I wanted something very Billie.”

In fact, Gimme Shelter, directed by the Maysles brothers and Charlotte Zwerin, and Pennebaker’s Dont Look Back were the only two touchstones Cutler ever referenced. “It was such a freedom to know we wouldn’t have to do sit-down interviews,” says Rosher.

“We knew this person was on a journey. There were a lot of hints that Billie was going to explode in some way.”

—Jenna Rosher

As a third-generation cinematographer, Rosher’s career path seemed preordained, but she didn’t take to it immediately.

Her grandfather, Charles Rosher, was a founding member of the American Society of Cinematographers, a favorite of actor-producer Mary Pickford, and a two-time Academy Award winner. (One of those honors, shared with ASC member Karl Struss for their work on F.W. Murnau’s 1927 classic Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, was the very first Oscar awarded for cinematography.) “I feel a deep connection to him, even though I never met him,” Rosher says, adding, “There was a bit of documentarian in him. When he went to film Life of Villa, [a 1912 documentary about Pancho Villa,] he was actually filming in Mexico during the Revolution.”

Her father, Charles Rosher Jr., ASC, followed in Charles Sr.’s footsteps. His feature work included the police drama The Onion Field, the Robert Altman ensembles Three Women and A Wedding, and commercial comedies like Semi-Tough and Police Academy 6: City Under Siege.

Jenna studied journalism, doing a brief stint in broadcast news before entering the world of nonfiction storytelling, which led her to pursue her family’s longtime calling. Her first time operating camera was for an MTV profile of young people living with HIV. “I found my way to cinematography via the nonfiction path,” she says.

For all of the vérité portions of The World’s a Little Blurry — captured in Eilish’s home, backstage, and in vehicles — Rosher shot with a Canon EOS C300 Mark II, usually mounted on a monopod. “My profile is super narrow,” she says. “It’s lean and no-fuss. Everything I need is on me: cards, batteries, lenses. I’m ready to go.”

Lenses were a mix of Canon models, including an EF 70-200mm f/2.8L, an EF 24-70mm f/2.8L, a CN-E 18-80mm T4.4 Cinema Zoom, a 35mm f/1.4L, and Canon Cine Primes. “I like to shoot vérité on primes,” she adds. “If I’m in an environment I can spatially predict, I shoot on the magic vérité lens: a 35mm prime. I use a little Cinesaddle for when people sit down. And that’s it!”

The crew was lean, too. Typically, just Cutler, Rosher and a sound person were inside Eilish’s house. “[Eilish’s family] eventually became so comfortable with us that we could just be in the house, hanging out with mom in the kitchen, then make our way into Billie’s room when she had something interesting going on there,” Rosher says.

Adds Cutler, “We have one currency when we make these movies, and it’s trust. Billie trusted her, heart and soul. She revealed herself to Jenna and Jenna’s camera. You can’t fake that.”

Rosher cites one example: Toward the end of the film, Eilish flips through her sacrosanct notebook, which contains notes and drawings that grew into the album. She finds a page that cries out with pain and depression, with references to cutting. “Wow, I was in such a bad place,” Eilish says on camera. Rosher recalls, “She opened up very quickly about it. This was many months after she’d written those thoughts and feelings, which were really dark. She was willing to say she was involved in self-harm. She says in the movie, ‘I thought I deserved it.’”

“I think it’s smart of them that they didn’t let

me have any say in it, because it shows more

of my life without me trying to

control the narrative.”

— Billie Eilish

While Interscope Records provided initial funding and Apple Original Films acquired the documentary, Cutler had final cut. He didn’t let Eilish or her family see any footage until the picture was locked. “I think it’s smart of them that they didn’t let me have any say in it, because it shows more of my life without me trying to control the narrative,” Eilish said in a statement. “To not see the cut of it for so long and not have a real say, it was torturous, but I think beneficial in the end, and I’m really happy it went like that.”

Eilish only offered suggestions to Rosher for the concert sequences — specifically, where to stand so the camera wouldn’t be in her line of sight or in the way of stagehands, plus the film’s final shot, with Eilish vignetted in blue flared light at Radio City Music Hall. Otherwise, Cutler states, “Billie in no way wanted to have control of this.”

“Every note I gave Jenna was ‘Don’t move

the camera. Don’t worry about the edit.

Just be with Billie.’”

— R.J. Cutler

For the concerts, “Every note I gave Jenna was ‘Don’t move the camera. Don’t worry about the edit. Just be with Billie,’” Cutler says.

“It was a relief to get that direction,” says Rosher — especially when she was shooting solo. “It relieved me of any necessity to cover something. I could just find a frame that felt right and stick with it. I would stay on one frame for the whole song and not move it. “I was with Billie for many, many shows,” she continues, “and over time you start to anticipate what she’s going to do. Like, I know she’s going to do one of those cool moves with her body when she’s dancing, and I know I need to be wider so people can see that. Then I know when she’s going to have her moment at the microphone and not do anything, so I’d go tighter. It was a great direction for me, because it took a lot of the weight off of feeling like I need to supply an editor along with what they need photographically. Instead, you’re supplying a beautiful, intimate moment with Billie Eilish.”

On the half-dozen multi-camera performances, Rosher says, “I was always with Billie, from backstage leading right up to when she walks onstage. Then I would transition to a stage-side camera.” The cinematographer swapped her Canon C300, used on all the solo shoots at concerts, for an Arri Alexa Amira or Alexa Mini. Multi-cam concerts at times also included a Sony Venice. All cameras were equipped with Arri Signature Primes or the Angenieux Optimo Ultra 12X 24-290mm T2.8 zoom. “We needed a camera in the crowd to capture all of Billie’s amazing fans, who are so affected by everything she does,” says Rosher. At New York’s South Street Seaport — venue of one of the only multi-camera concerts that ultimately made it into the film — cinematographer Jessica Young focused on the crowds while Kenny Stoff was in the front pit. Both played key roles at other times, too, with Young shooting an early performance in Salt Lake City, and Stoff supervising the official cameras at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival.

Of this latter performance, Cutler says, “Coachella had 14 cameras shooting performances. You can’t bring your own — they’re very restrictive. Kenny Stoff was leading the camera team, and we had faith in the operators he brought onboard. They were kind enough to share their footage with us.”

A priceless moment at Coachella — when Eilish meets her childhood heartthrob, Justin Bieber — was captured by Eilish’s mother on a cellphone. But Rosher got her own moment, backstage at the Grammys, when Bieber called to congratulate Eilish on her success. This, too, was captured on an iPhone. “The Grammy folks didn’t mind if a member of Billie’s entourage had an iPhone, but they controlled the camera crews, [who were] cordoned off,” Cutler says. “Well, we didn’t want to be cordoned off in the press areas. We wanted to be with Billie backstage, both before and after the show. The only way to get that was for Jenna to be part of her entourage, shooting with an iPhone [11 Pro].”

Cutler adds, “Jenna was in the moment when Justin Bieber called, and it was perhaps as critical a moment as any that night.”

Looking back, Cutler likens that year to riding a wave. “And the waves were very high,” he says. Rosher agrees, adding, “We felt blessed. Billie was so willing to show everything. Her openness and her raw, real character were so fun to film. It was just a joyful experience to be there.”

- 1.78:1

- Cameras: Arri Alexa Mini, Amira; Canon EOS C300 Mark II; iPhone 11 Pro; Sony CineAlta Venice

- Lenses: Canon L-series prime and zoom, CN-E prime and zoom; Arri Signature Prime; Angénieux Optimo Ultra zoom