Fantastic Voyage: Creating the Futurescape for The Fifth Element

Digital Domain’s imagery experts help to create eye-boggling visual effects for Luc Besson’s sci-fi fantasy.

If the box office smash of the Star Wars Special Editions proves anything, it's that audiences are hungry again for what purists once disparagingly referred to as "a space opera." However, French director Luc Besson's audacious new film, The Fifth Element, owes less to George Lucas than to the absurdist sensibilities of Jean-Luc Godard. Likewise, the film's intense imagery was dreamed up in part by French artists Jean "Moebius" Giraud (of the Gallic graphic magazine Metal Hurlant) and Jean-Claude Mezieres (Valérian: Spatio-Temporal Agent), who, along with production designer Dan Weil, helped Besson visualize a fantasy film which the director had nurtured for nearly 20 years. Along the way, the filmmaker refined and expanded his ideas to include every effects innovation of the past two decades.

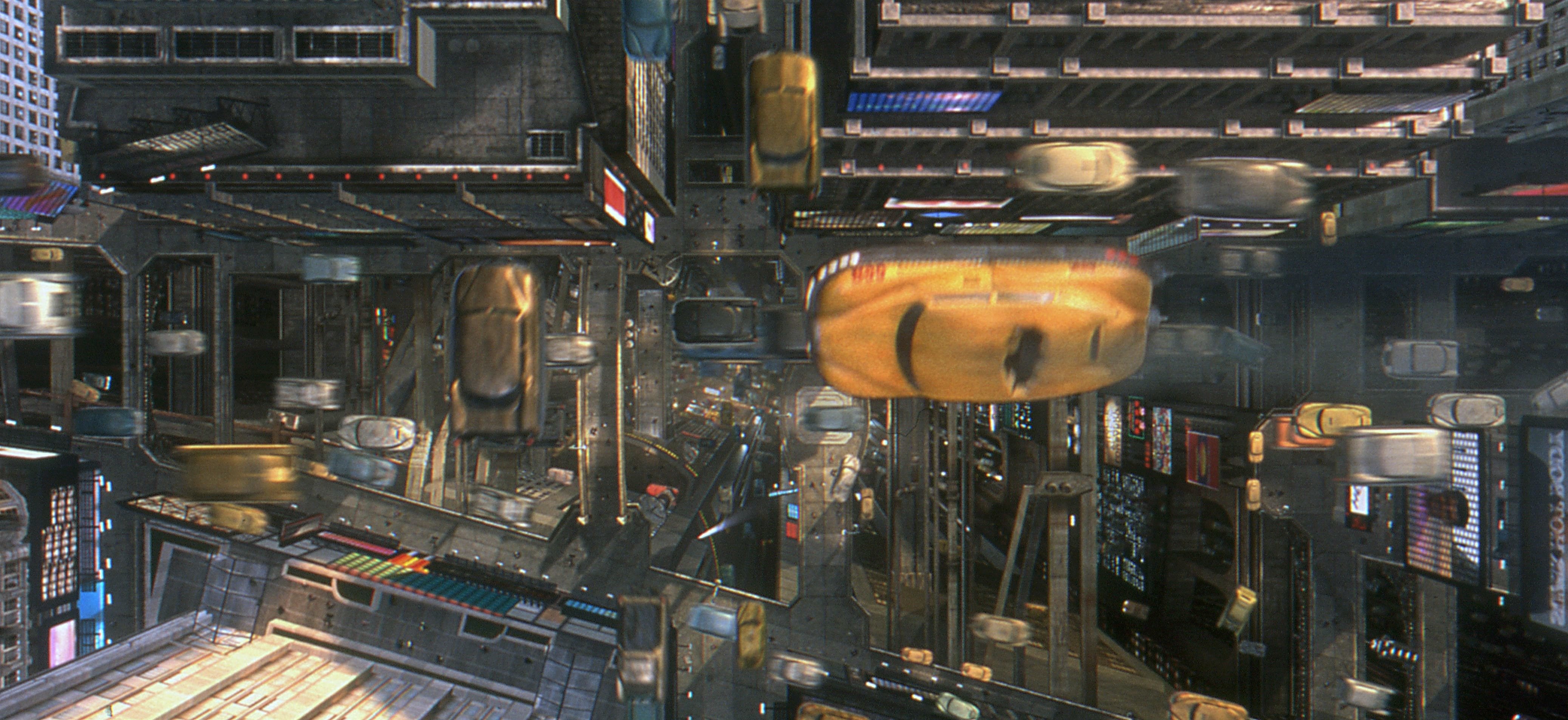

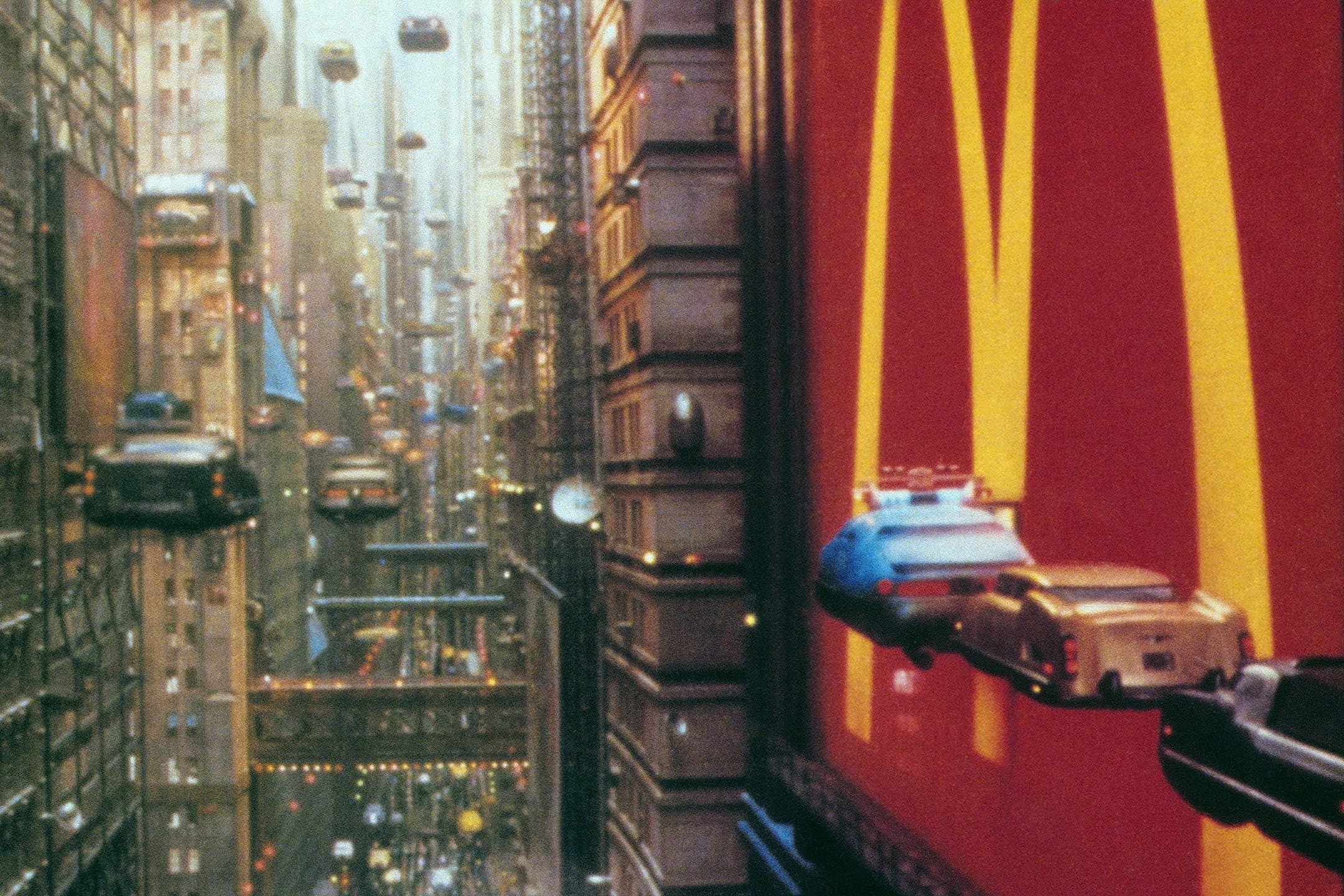

The result is a visually stunning, living comic book that plays out across a fully realized galaxy — from a New York stretching 600 stories in every direction (complete with traffic jams caused by flying cars) to a luxurious outerspace pleasure ship cruising over a water planet. The Fifth Element's far-reaching vision of the future demanded a virtual "sampler" of visual effects, and Besson chose Digital Domain to achieve it all.

Approximately 85 model makers and 85 artists worked on finishing the film's 220-plus effects shots at any one time. Leading the pack was first-time visual effects supervisor Mark Stetson. A former model maker (Blade Runner, The Hudsucker Proxy), Stetson closed his shop, Stetson Visual Services, just after completing a colossal miniature of the ill-fated Exxon Valdez for Waterworld. Within four months, he joined Digital Domain on The Fifth Element.

Assessing the duo's on-set relationship, visual effects producer Dan Lombardo (The Island of Dr. Moreau) notes, "Luc is the type of director who is very hands-on with every aspect of a production. On this show, he didn't delegate a whole lot, except when it came to something he didn't know very well. That's when he'd lean over to Mark and ask him to step in."

Stetson himself affirms, "It was great to have that kind of relationship with Luc, who is normally extremely private and protective. The movie's design was heavily influenced by the look of Seventies' French comic books, which made it really fun to work on. Although part of it takes place in a futuristic New York City, I think the setting is quite different from the Los Angeles of Blade Runner. The flying cars are a lot more whimsical, and the city is set in broad daylight. The film is rooted in a much more utopian vision of the future than Blade Runner, which virtually defined the post-apocalyptic look of futuristic films for more than a decade."

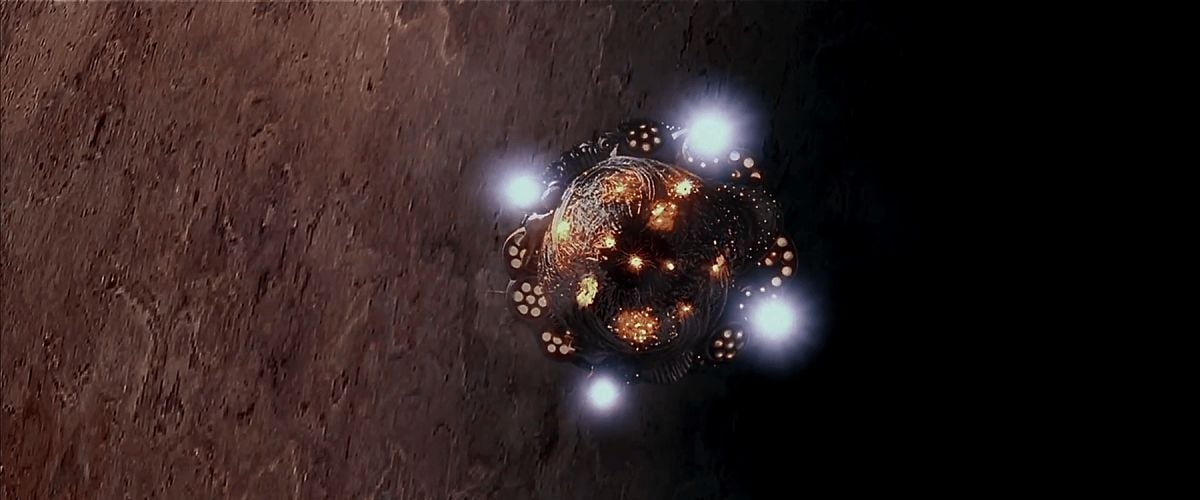

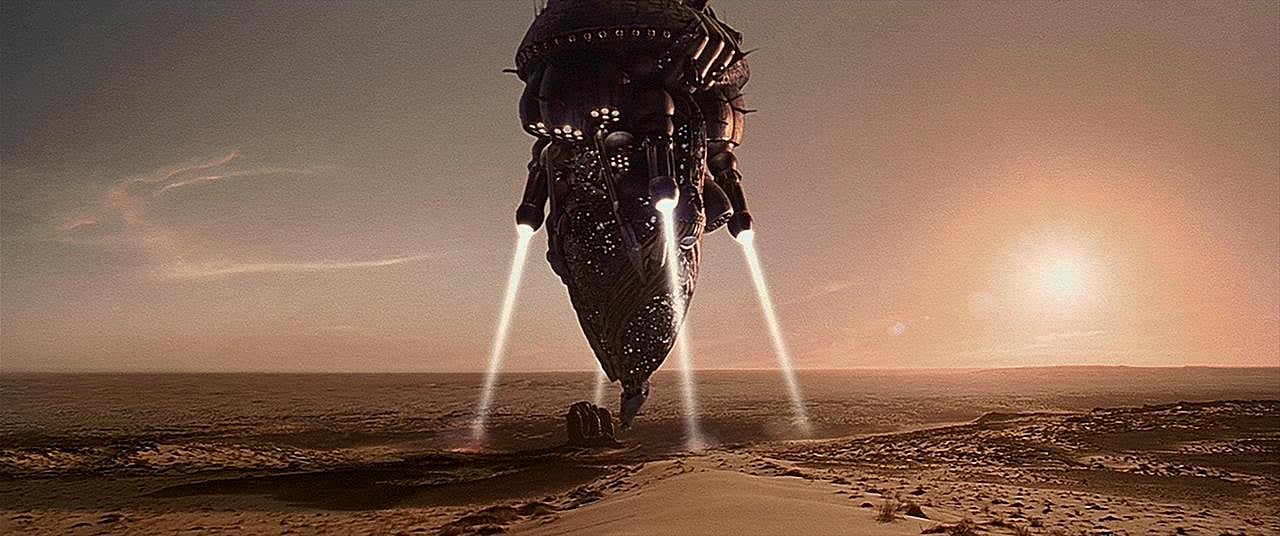

The Fifth Element opens in early 20th-century Egypt as a spaceship — piloted by a saintly race of aliens called the Mondoshawan — descends toward Earth. A pleasing, rusty red hybrid of a conch shell and a football, the alien craft was designed by Metal Hurlant artist Moebius, and was constructed as an 8’ miniature by Digital Domain's model shop; a digital matte painting derived from NASA photographs doubled for Earth.

Upon arriving, the oval Mondoshawan craft hovers on energy beams above a bizarre rock temple. The production crew painted a doorway on a gigantic rock rising from a dry lake bed, transforming it into the temple exterior. Most of the plates were shot by Besson and Fifth Element cinematographer Thierry Arbogast, AFC, with Digital Domain's visual effects director of photography, Bill Neil, acting as an advisor.

After a decade working as a camera assistant and camera operator, Neil began his effects career at the then-fledgling Industrial Light & Magic as an equipment designer and camera assistant on The Empire Strikes Back and then became a camera operator on Return of the Jedi. Neil subsequently went to work at Boss Film, where he first met Mark Stetson in 1983, before joining Digital Domain a decade later.

Neil had worked with demanding directors in the past, but Besson insisted that all of his creative options be left open — a caveat which could have spelled trouble for visual effects work. "We shot a number of alternate background plates — different angles — and it was only in the editing phase that we saw what was going to work," Neil recalled during a recent phone conversation from London, where he was about to begin work as visual effects supervisor on the upcoming James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies. "I didn't have a camera crew, so Luc and Thierry photographed all the plates, and I helped them technically with post issues."

Besson had a very symmetrical, center-weighted cinematographic style in mind for The Fifth Element. While the director had shot his previous films in 2.35:1 anamorphic, The Fifth Element would be shot in Super 35, partly to accommodate the intense visual effects demands. This decision meant that the production didn't have to shoot VistaVision background plates or use duplicate camera packages. The main unit used Arriflex cameras, and Stetson, Neil and company reluctantly agreed to use the Arris for their effects work. "We were skeptical," Neil admits. "We tried to push toward Panavision because we felt we had a better chance of having a steady plate camera, but the Arris were pretty good. The production was using the Arri 535B, and most of our plates were shot with a production camera. We also used a prototype of the new 435 high-speed camera. About halfway through production, Arriflex replaced our prototype with one of their first production 435 cameras. I was amazed at the performance of this camera in terms of its steadiness at all speeds. In fact, it was rock steady, good enough for matte work from two frames to 150 frames a second — in both forward and reverse. I've never seen any camera made anyplace in the world that could do that."

While the Arris proved their worth, the effects team was concerned about stories of cameramen who refused to shoot Kodak's European-finished stocks because of steadiness issues, and convinced the production to import Rochester-finished emulsions for anything that was to involve visual effects, as well as the surrounding footage. Ultimately, Arbogast used Kodak 5293 for non-effects sequences, and shot the picture's considerable amount of greenscreen work on the slower 5248 stock. While most effects plate interiors were shot on 5293, Neil shot some plates of the "vertical hunk of rock" that served as the temple on 5245 at "quasi-magic hour.

Though the Mauritania plates were filmed prior to a formal design of the effects shots, Stetson says that the series yielded "a nice sequence of six spaceship shots." The 8’ Mondoshawan spaceship miniature was shot by Neil's visual effects co-cinematographer, Paul Gentry, who matched the model lighting to the plate's rosy sunset look as the Mondoshawan visit the temple and then lift off again.

According to the film's storyline, the Earth finds itself in crisis in the year 2259 A.D. The Mondoshawan are on a mission to bring all five elements to Earth when their mothership is shot down over an alien planet by the dreaded Mangalores (realized with excellent alien designs by Nick Dudman). As envisioned by Besson and Stetson, their tiny ZFX 200 fighters make a dynamic dive on the massive Mondoshawan craft, raking its surface with fiery missiles. "We shot the move on the Mondoshawan ship first, then did different moves on the little ZFX 200 fighters," Stetson remembers. "We had two scales for the miniature attackers: a cleaned-up design maquette measuring about 16" long was used for long shots, and a 4' miniature for close-ups.

The camera follows directly behind the devastated craft as it crashes into the planet's surface. Flames erupt through its shell, which crumples on impact, recalling the destruction of the Hindenburg. "I think Mark patterned it after an actual crash he saw on film where a pretty sizable jet plane crashed into the ground at an airshow," Neil says. "It went in at high speed and disintegrated little by little from the nose to the tail. That was the guiding principle: this thing was boring in and breaking up beyond the diameter of the ship, whose width covers the impact point."

The "destruction" of the Mondoshawan ship was shot on a soundstage. "We turned the whole environment 90 degrees, so we were looking across the stage at the tail of the ship and pulling our motion-control camera back," Neil says. "We created interactive lighting effects, like firelight, as a sweetener to help join the model to the pyrotechnic plate."

"No models were harmed during the creation of the sequence," Stetson adds with a laugh. "That was sort of a philosophical thing. I was dealing with a space fantasy here, but I didn't want to do another big 'miniature explosion' movie. I didn't want to build a huge 40’ spaceship, drop it into a planet surface and explode it; I wanted to do something a little more violent with the actual explosion and then just scale the ship into it. Scott Rader tracked in a lot of surface explosions to the miniature — some that we had photographed and some from the Digital Domain pyro library. We then followed the Mondoshawan ship as it crashed into the red planet, which was a typical 'Luc-vision' shot looking straight down the tail of the ship as it impacted the surface.

The massive explosion that results involved a huge pyro shoot at Indian Dunes. "The planet was a patch of ground about 50' wide by 125' deep, which was sculpted very carefully with little craters," Neil reports. "We chose that spot because it gave us late afternoon light and was relatively flat; we could do pyrotechnic events without starting grass fires. Thaine Morris and his associate, Ilya Popov, assembled a huge system of 45 to 50 mortars set up in a ring in the center of the landscape so they'd all blow from the center out as the ship hit. They also set up primer cord around the outside to create a spray of debris. It was a very cleverly choreographed pyrotechnic event. We put two small, high-speed Photosonics 4ML cameras side by side and bracketed the frame rate because additional camera costs were small compared to the cost of dressing the set. We did two formal takes. The final frame-rate was around 1OO fps. We shot on 5293 because it was fairly dark late in the day, and I wanted to hold the depth of the pyrotechnics."

Aside from creating stylized but believable space battles, Digital Domain's crew had to envision Evil (with a capital E) for Besson's fantastic tale. Audiences first glimpse Evil when a massive warship encounters a glowing, planet-sized ball of lava. Responding to its potential menace, a phalanx of cruisers fire three missiles at it. This tactic, however, only serves to make the vast orb larger — and angrier. When the warships foolishly fire more missiles into Evil, the sphere spits out a ball of flame that engulfs the craft.

The Evil effect was realized with Renderman, Prisms, Alias and proprietary software manipulated by a crew of CG artists overseen by digital effects supervisor Karen Goulekas. "We worked for a long time to develop the look of the crust and lava, and the activity that occurs when they meet," Goulekas says. "We developed a three-step process to create the look of the surface that greatly reduced rendering time. First, Paul Van Camp wrote a fractal generator to create fractal-animated texture and displacement maps of lava and crust. Then, additional twisting and bulging was added on top of these maps in Elastic Reality, a 2-D morphing program. Finally, the resulting maps were fed into a Renderman Shader to apply the crust and lava and their accompanying displacement on a sphere based on height fields, which condensed six hours of render time to a half hour per frame."

Evil often appears to be a deceptively simple presence, but Goulekas found the amorphous anomaly terribly complex to animate: "It wasn't easy to control the lava and the crust, because Luc wanted Evil to do some really specific things: when it closed up, it had to crust over and turn black, after which the crust had to rotate. The hardest thing was making Evil get angry and grow when the missiles were shot at it. Luc didn't want it to just scale up, which would have looked as if we were zooming in on a sphere, and neither did we. Using math expressions, Paul Van Camp came up with a way to expand it in a very non-linear fashion so the ball became more amorphous and felt as if it were actually growing."

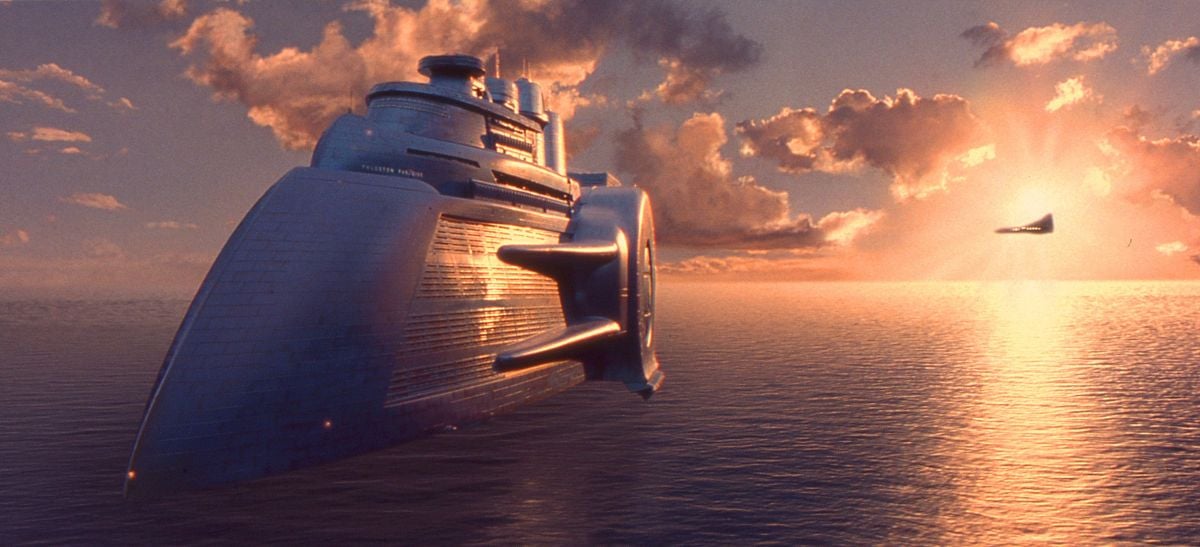

As Evil encroaches, Besson returns to outer space sporadically throughout the film. After the film's protagonists — cab driver Korben Dallas (Bruce Willis) and the cryptically beguiling Leeloo (Milla Jovovich) — meet on Earth, they take a space shuttle out of New York City and rendezvous with a spectacular 2,000’ pleasure ship (the Fhloston Paradise) hovering above the surface of an idyllic water planet. Their mission: rendezvous with an alien opera diva aboard this futuristic Love Boat.

The diva sequence begins as the space shuttle docks with the orbiting cruise ship, which sports a garish paint job in a hue that Stetson terms as "candy apple blue." Naturally, the reflective nature of the paint made the 8’ miniature difficult to shoot. As with all of The Fifth Element's models, Bill Neil shot the Fhloston Paradise using the backlit UV technique Digital Domain pioneered on Apollo 13. The frontlit beauty, key and fill passes were filmed against black; a backlight pass was then shot, with a screen painted with UV-sensitive paint positioned behind the model. When hit with a Kino Flo, the screen fluoresces a very narrow bandwidth frequency of red, making the model appear as a black silhouette against red. The backlit image only registers on the red layer of the film, creating a perfect matte while allowing a fair amount of reflective glow to extend beyond the model's surface — an extra touch that would have been lost using traditional greenscreen techniques.

Neil had concerns about how the intensely blue spacecraft would appear when photographed. He recalls, "It was quite shiny initially, so we found a good balance between gloss and semimatte, where it picked up the light nicely and still had some sheen to it. I did some lighting tests, wedging the miniature to see how it behaved in the light, and found that by overexposing it significantly, it just got richer and richer. It was strange; the paint itself actually glowed. I played around with the exposure until I found a look I thought was suitable to a tropical environment."

In keeping with the diva sequence's color motif, a stunning blue alien, replete with six tentacles protruding from her head, sings before a packed concert hall aboard the cruise ship. Angles looking over the diva's shoulder at the crowd were actually shot on location at London's Covent Garden Royal Opera House, but the reverse angles were shot against green screen on a stage at Pinewood Studios. The greenscreen shots were originally supposed to be lockoffs, but when Stetson, Goulekas and Neil arrived on the set, they found that Besson had once again set up dolly tracks.

Mike Bergstrom, who handled the encoding equipment, quickly swapped the head on the production camera with a duplicate encoding head. Goulekas plastered the greenscreen with ping-pong balls for tracking reference points. Meanwhile, Stetson was concerned about the reflective sheen of the diva's costume. "[Makeup artist] Nick Dudman used a material that was very specular and diffractive," Stetson says. "When we looked at the green screen element of the diva in this shiny blue suit, we thought, 'Oh God, what are we going to get out of this?'"

Fortunately, Neil had been busily advising his first-unit colleague Arbogast to ensure that the effects team received a solid green screen backing. "I convinced Thierry to adjust his lighting in order to improve the possibilities of pulling mattes off this semi-metallic costume" Neil recalls. "He added some sidelight to the stage; he hadn't originally planned to do that, but it helped us to control the green spill from the costume."

The fun really began once Stetson and Goulekas returned to Digital Domain, where the entire background — including a huge picture window framed by giant steel arches, offering a view of the planet Fhloston floating in space — was created as a 2-D digital matte painting. The blue water planet itself was a CG creation, with digitally painted skies and clouds created by art director Ron Gress.

Although Besson and Arbogast shot the diva's performance from the dolly track, Goulekas reports that "Luc pretty much delivered lock-offs with a little bit of camera drift in them, so we figured we didn't have to go with the encoded data, we'd just go traditional 2-D, track the ping-pong markers to get our X and Y translation curves, and then apply them to our CG background."

Despite the apparent ease of lining up the 2-D matte, Goulekas' team was sweating to create the correct perspective for the stage and arches by eye. In a breakthrough concept, Goulekas and compositing supervisor Jonathan Egstad imported the encoded dolly move into Nuke, Digital Domain's proprietary compositing software. "Suddenly, all of the tilts, pans and elements looked correct," Goulekas marvels. "There's actually a 3-D tilt on the matte painting of the arches, and the shadows cast by the arches onto the stage were mathematically worked out to move in perspective along with the camera. I'm pretty proud of those; they really involved a lot of three-dimensional thought and built-in camera perspective."

A similar technique helped tie The Fifth Element's most spectacular blend of miniatures, CG models and digital matte paintings together in an awe-inspiring police chase through a futuristic New York City that extends 200 stories above the old city streets and 400 stories below. Both the police cars and their quarry, a beatup cab belonging to Korben Dallas, are airborne — as are all of the other cars in the scene.

The complexity of creating these squadrons of flying vehicles convinced Karen Goulekas of the need to devise a procedural pipeline that would enable many artists to generate traffic, and to employ the same software in the pre-visualizations her team was doing for Besson. Thus, in theory, the preparatory camera moves could later be translated to the motion-control stage and employed to blend the miniatures, CG models and matte paintings together. "In London, we used Silicon Graphics' Prisms software for the pre-vis," Goulekas says. "It was our first big pre-vis ever at Digital Domain, so initially there was an inclination to do it with a less expensive software package. But I really balked at that idea. Rather than re-creating the pre-vis for real on another software package, Mark wanted the pre-vis to be able to roll right into production. That way, we could cut together the whole sequence with flat-shaded cities in CG; when we got back to Digital Domain, we could send those tapes out to stage so the crew would not only have a camera curve, but also a visual animation of what the shot was supposed to look like."

Beyond establishing camera moves and shot angles, the Prisms pre-visualization helped Stetson and model-shop supervisor Neils Neilson determine the scope of miniature construction. Cunningham set up the software so that he could alter the scale of the buildings without having to reanimate each shot, which enabled Stetson to experiment with various scales until he found the perfect match for the height and width of Digital Domain's motion-control stage. "We modeled the stage environment as well," Stetson explains, "so we could see whether or not our miniature cityscapes would fit into Digital Domain's stage. Then we color-coded the buildings in the pre-vis so we knew when we were past the limits of the stage."

"It was a bounding box," Goulekas adds. "As soon as we got 30' or 40' out from the camera and hit the stage floor, everything that got rendered out turned red, so we automatically knew what was CG or a matte painting or miniature buildings."

Stetson passed drawings and blueprints back and forth to effects art directors Ron Gress and Ira Gilford to get the cityscape designed and into Digital Domain's model shop, allowing construction to begin before Stetson returned from England. This was a stressful process since Besson and production designer Dan Weil insisted on a retro vision of New York City that would maintain the regimented order of its streets even as it climbed hundreds of stories upward. Some of the structures had to look as if they had been built right on top of older buildings, which would be squared off under reinforced glass cases.

“One of Dan Weil’s earliest statements to me was, ‘A Frenchman looks at Manhattan and sees a completely different city structure than a classical European city.’ Unlike Paris or London... New York doesn’t have curves or T-intersections — it’s all about the grid.”

— Mark Stetson

"Luc and Dan saw our cities differently than any director and production designer I've worked with before," says Stetson, "and I've built New York probably six times! One of Dan Weil's earliest statements to me was, 'A Frenchman looks at Manhattan and sees a completely different city structure than a classical European city.' Unlike Paris or London, with their rat's nests of tiny streets, New York doesn't have curves or T-intersections — it's all about the grid. New York has perspectives to infinity, which corresponded very strongly with Luc Besson's cinematographic style for this picture — center-focused, with one-point perspectives and vanishing points at the crosshairs."

Although to creating streets that seemingly stretched on forever proved difficult, Stetson eventually went with 1/24-scale for Element's New York City (the same scale he had employed for The Hudsucker Proxy and The Shadow). "A scale of 1/24 is about as small as you can get for modern cameras," he says. "We had maybe 24 to 30 miniature buildings and they were quite large — up to 24' tall by 40' deep, which filled Digital Domain's main double stage. We had a few shots that were entirely miniature backgrounds, but most of the time we ended up extending the set very creatively with 2-D matte paintings. There were about five shots in which the cityscape was entirely represented by CG. But there was very little live-action production representation in terms of exterior sets for the city. It was left almost entirely to us."

With Stetson, Goulekas and Neil still in England shooting the few full-scale setpieces for Leeloo's escape (in which she first sees the enormous New York megalopolis before falling into Korben's cab and leading the police on a chase above and below Times Square), Digital Domain's model shop got the miniatures to stage. "A month after we got back, we started shooting models," Stetson recalls. "For the first time at this facility, Karen was able to actually export camera moves to stage. Instead of it being a one-way street — with motion-control moves recorded and then sent to the CG world — we actually put the pre-vis camera moves into motion-control files. Sometimes that worked as advertised, and sometimes it only panned out to a lesser degree. Next time, we'll make a more accurate CG model of the motion-control axes so we can mimic the camera's moves and limitations more exactly. Still, we created that pathway, and we're proud of it. We looked at each other after it was done and said, 'We actually succeeded!'"

The 3-D space in the pre-visualization didn't always relate to the physical stage, but effects cinematographer Bill Neil and his associate, Paul Gentry, found it to be useful, if only as a timing guide. Neil explains, “It was a wonderful communications tool between the visual effects team and the director to help clarify what his vision contained, and to reach a common understanding."

Neil insisted on shooting the city background plates before filming the cars in order to create interactive light on the vehicles that would relate to their environment. Although Besson's center-focused perspective ran contrary to Neil's experience in composition, the cameraman found that it offered some interesting problems to solve — such as creating depth when shooting a limited number of buildings being elongated to infinity via digital matte paintings.

Adding to this challenge was Besson's directive that the sequence occur in broad daylight. "I was shocked," admits Neil. "Miniatures are often saved by the fact that you don't see much of them, but this whole sequence took place late in the day, and it had to hold up to scrutiny. The stage ceiling was only a few feet above the top of the buildings, so we did tests to see how we could light that expanse of vista. Fortunately, my gaffer, George Ball, and my key grip, Joe Celeste, were able to realize my ideas on the stage. We had a general skylight that came from the top, and then a golden key light that was supposed to be the late day sun raking through any gaps between the buildings. But instead of having key light all coming from roughly the same direction, I took what I came to call a 'fractured light approach,' where I added broken light coming off buildings that were not in frame, often at steep angles, reflecting back in the opposite direction from the sunlight key. That gave the city an energy, a modulation of the light that was quite wonderful.

"I also built aerial perspective into the scene so that as the distance from camera increased, the contrast of the scene decreased. Dark things become lighter and light things become darker until ultimately they become monotone. I took that into account in my miniature lighting, and that carried through in the matte painting, which gave us great depth in the streets."

Stetson had set some basic specs for the kinds of motion-control rigs needed to shoot down into the canyon of buildings toward the floor: "I wanted to fly the camera from the stage ceiling down into the miniature, so we put the camera on a cruciflex motion-control rig, a motion-control crane with a vertical tower for descent and a horizontal crossbeam for forward motion."

Stetson also planned to thread the camera on a 20' extension arm through the miniature streets. At four feet wide, the streets were too narrow for Neil's motion-control camera to run along a horizontal track between the buildings. For the chase's climax, when Korben's cab is pursued below the city through a girder-walled tunnel beneath an underground railroad, Stetson expected Neil to use the extension arm to travel into the 1/6-scale tunnel model. Although the miniature set measured 48', it still wasn't long enough for the high-speed chase. "We made it appear twice as long by shooting it twice, the second time with the camera displaced 48' back," Stetson says. "We needed a very long camera track and two sets of mattes to complete it, but the pieces lined up perfectly with Karen's help. The tunnel chase was almost entirely miniature. Brian Grill some CG debris, some 2-D debris, and smoke resurrected from prior shows to sweeten the scene. The cab is in the foreground, the vanishing point is in the center, and there's a lot of weaving and bobbing."

At five minutes and 70-plus shots, the cab-chase sequence represents nearly a third of Digital Domain's Fifth Element effects. Most of the shots involve CG traffic, and sometimes CG hero cabs and police cars. "We digitized the 1/6-scale [models of] Korben's cab and the cop car," Goulekas says. "The hero police car dive down following Leeloo's jump was done in CG because we wanted to see all six surfaces; there was no place to hide an armature mount. You'd be surprised. Our CG traffic pipeline enabled us to say, 'We want a certain percentage of cabs, police cars, red cars, blue cars." The artists worked with low-res versions of the traffic, and then we'd substitute the real traffic on the output on the Tenderer."

Sequence supervisor Sean Cunningham coordinated the creation of all of the pieces for the cab chase, and shader supervisor Simon O' Connor conceived all of the shaders and surfaces for the traffic. But putting all the different elements together fell to compositing supervisor Egstad. "Getting the color balance and the contrast range of all the objects matching properly in daytime was a big challenge," Egstad says. "We composited hundreds of computer graphics cars, which wouldn't fit unless we blurred them a little and boosted their contrast. Also, matte edges aren't nearly as forgiving, so we used a number of different atmospheric tricks, like adding density fog and using filters in Flame to add a nice optical glow from headlights and take the curse off the CG objects."

Amid the craziness of production, Stetson was left to his own artistic instincts in terms of directing the development of the cityscape — a potentially dangerous situation. "We'd walk Luc onto the stage when we were shooting, but he'd just look at stuff without any reaction, because he was totally absorbed with directing his actors," Stetson recalls. "Had I been really wrong about what Luc wanted, it would've cost us horribly in terms of time and money.

"Finally, when we had traveled way past the point of no return design-wise, I went to his editing suite in Malibu and showed him a color print of a test shot of one of the first big model setups of the city, which represented hundreds of thousands of dollars' worth of work. Up to that point, it was unknown whether he was going to bless it or not. Luc looked at it and his face just lit up completely. He held up the picture to show his editor, Sylvie Landra, pointed to it and then pointed to his face with this big smile on it. He really loved it. That was a huge relief."

For more on this production, from the same issue: Astral Grandeur: The Fifth Element Offers a New Sci-Fi Aesthetic.

Besson would later adapt Jean-Claude Mezieres’s Valérian: Spatio-Temporal Agent into the film Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets (2017), photographed by Thierry Arbogast, AFC.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.