Filming 12 Angry Men On A Single Set

Carefully planned lighting and camera angles played an important part in giving impact and suspense to the drama of 12 men deciding the fate of another in the confines of a small, hot jury room.

This archival article originally appeared in AC, Dec. 1956

The ever-present challenge for the director of photography is how to give each new picture a new and different camera treatment — a fresh viewpoint, camera-wise. Lest he repeat himself and fall back on old techniques, the cinematographer is continually challenged to dig deep into his bag of tricks so that his photographic technique does not become stagnant.

Sometimes an assignment is filled with more problems and difficulties than others, as in the case of 12 Angry Men, which I recently photographed for Orion-Nova Productions in New York. Just one look at the script convinced me that here was truly a challenging assignment — photographing a dramatic story within the confines of a single, one room set.

“In good cinematography the camera should never distract the audience from the basic theme and never move without justification.”

The story concerned 12 men who, as jurors, find themselves locked inside a jury room where they must decide whether a young boy, on trial for his life, is to live or die.

Considering the one-set limitations, the first and most important problem was how to keep the photography of this picture from becoming static; the entire story was to be staged and photographed in a room no larger than an average hotel room. The second problem was how to present cinematographically the psychological study of 12 men, each from a different social strata of a big city and whose only common denominator was that he had suddenly found himself in a jury room, and was being asked to pass judgment on the guilt of another human being.

The first problem presented the biggest challenge. I had experienced this type of a problem before in one or two pictures, but in a much more fleeting way — for perhaps a sequence or two. But here the entire story was straightjacketed inside a one-room set. Inside a jury room, in which sat 12 men, whose backgrounds, attitudes, problems, and reasons behind their decisions had to be shown photographically as well as in the dialogue.

After much thought and discussion, we decided there was only one way to overcome the possibility of static cinematography. That was to turn the disadvantage of the single set into a pictorial advantage. We decided to use the camera to play up the feeling of confinement and thus contribute dramatically to the total expression of the story, making the confinement an integral pictorial part of the mood.

In good cinematography the camera should never distract the audience from the basic theme and never move without justification. And yet the static condition inherent in the one-set limitations of this story had to be overcome. The camera had to reveal at the outset the basic character of each man, and his personality traits had to be elaborated upon later in the film to reveal the inner psychological reasons for his behavior.

Because of this the opening scene was the longest, single continuous take I have ever done in all my years as a cinematographer. It ran for seven consecutive minutes. It was made up of 18 separate camera movements which actually showed 18 basic fact situations. It also established the basic style and mood of the picture.

During this seven-minute take the camera introduces the twelve men in a very casual way as they bump into each other and exchange casual remarks which are not at all related to the case on trial. Yet in this way each character immediately begins to relate to every other man in the room and to the story. From the moment the foreman calls for the first vote we are caught up in a tight, tense drama which never breaks until the end of the film. The screening time is exactly equal to the actual time depicted in the story. Thus, in the hour and one-half the jury spends in the jury room it was impossible to break away from the continuity of the story, to flash back, or attempt a time-lapse. There was nothing for the camera to do except to show one direct continuing story carried further and further along inside the small, hot, locked room.

This picture was shot only one way, to be edited only one way. We didn’t “protect” ourselves in the usual way, but decided on the spot how the sequence was to be shot.

Therefore, each angle was checked to determine the best composition with respect to the visual impression we were seeking, and to the action involved. So that when it came time to roll the camera, everybody concerned knew exactly what they were going to do.

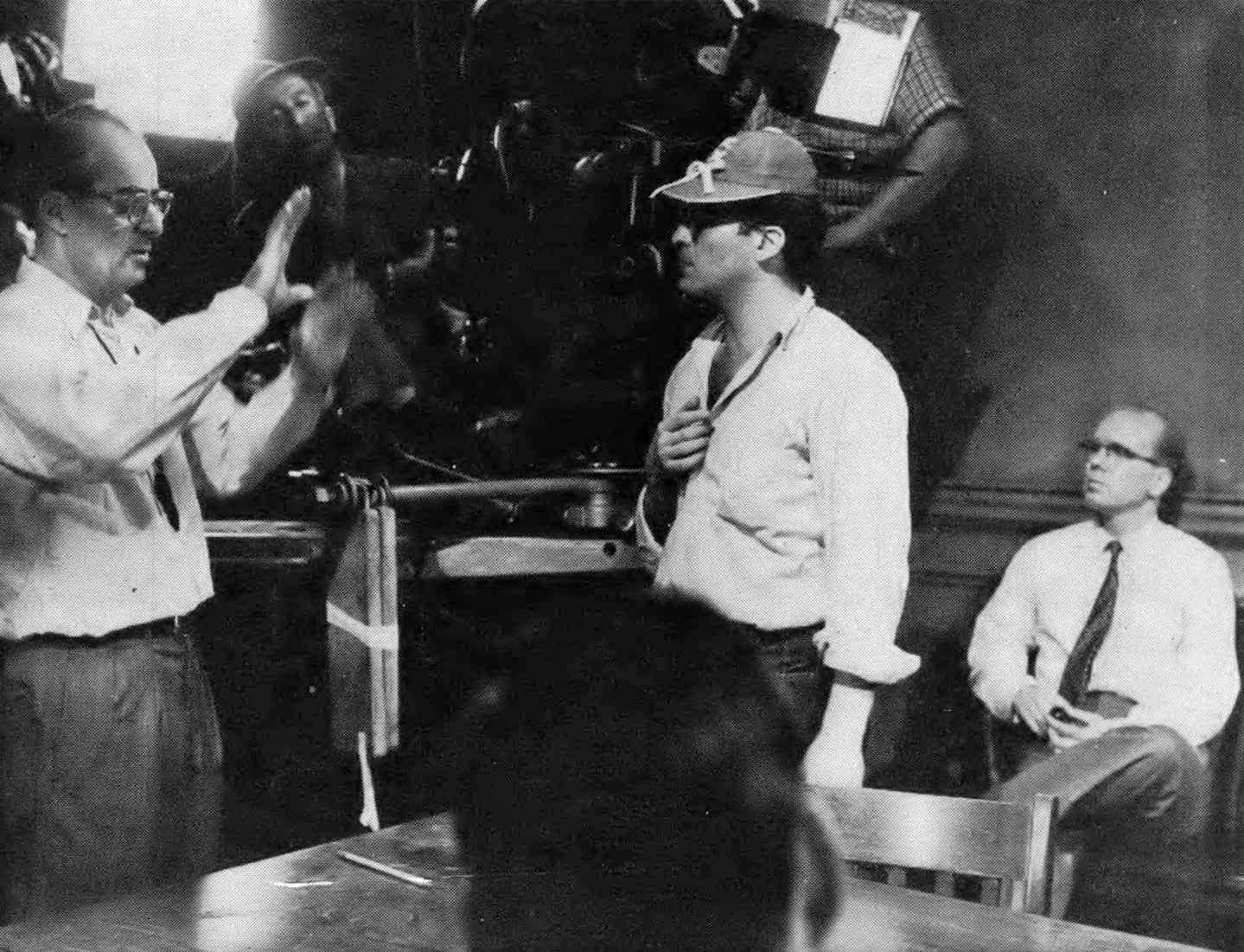

The directing technique employed stemmed to a great degree from Sidney Lumet’s television background — where, because you are only allowed one take during the actual show, everything is ironed out during rehearsal. Which, when you have as fine and sensitive a feel for camerawork as Lumet, plus his talent and memory for details, combined with a tight script by Reginald Rose, and sensitive performers like Henry Fonda, Lee J. Cobb, Jack Warden, and others in the cast, can prove to be a very successful method of filming a motion picture.

There was another pictorial technique we used to emphasize changes in the mood of the story and in the interlocking themes of the plot. This was in the basic lighting patterns, three in all. First, the lighting suggests bright daylight as the hot afternoon sun shines through the windows as the jury files into the room.

The second stage is reached when the action in the room becomes tight and charged with the oppressive heat of the summer day; the camera moves in again and again to show the tense, electric undercurrents related to the drama going on between the men of the jury. This effect is then heightened by darkening skies in the background, a sudden darkness in the room, and the sound of thunder off in the distance.

And finally, the pictorial effect of a rainstorm which pours down on the city, and breaks the tension within the room at the height of the emotional battle that has been going on for over an hour and a half. The camera makes the most of the effect of the sight and sound of rain beating against windowpanes, raising the tension of the jurors to the highest point as the last of them finally admits there is room for doubt. The storm breaks only after the jurors’ fateful decision has been made.

As we cut to the exterior of the Courthouse, with a wet column heavy in the foreground, the men of the jury disperse into the city and the anonymity of the crowd with nothing more to remind us of the drama that took place behind the closed doors of the jury room. Except the coming of night and the wet pavement as the 12 Angry Men fade into darkness.

Click here for more archival stories from American Cinematographer.